This checklist was created in the module: "Management of Scientific Data" and should give you an overview on how to describe your dataset and workflows, the way the future you and other researchers are able to use it.

This is the most important of the following points: Use a metadata standard. Most points following should already be covered by your chosen standard, so it is a very good idea to pick a standard an then stick to it. The standard itself should be easily accessible and widely known, at least in your field. If this is not possible, make sure to preserve the scheme itself and its documentation along with your data [1].

But how to pick a metadata standard? There are many types of metadata standards. Some are generic like Dublin Core, while others are specific to a field of research. When choosing your standard, start by asking for your organization's policies. In most cases, they already chose a standard and encourage you to use it. In other cases the publisher specifies what standard to use. If neither your organization, nor the publisher specifies the standard, chose the standard by the field of research or the data that is available to you. For further information, see Metadata standards overview.

https://xkcd.com/927/

Enter the name of the dataset or the project that produced it. If you choose to name the dataset according to the data, be as specific as possible. Do not use special characters, underscore and hyphen are okay though. Other than that, the format is freely choosable.

Enter the Names of the researchers, that are mainly involved in creating the dataset, or the authors of the publication in order of priority. One good practices concerning names in general is transcribing names in Latin script, when coming from another writing system. ALA-LC (American Library Association - Library of Congress) is a set of standards for romanization, that can help you with this topic. For further information, see ALA-LC.

Add the name of the funding organization or institution. Most organization have policies for this, so ask your mentor or supervisor if you're not aware of those.

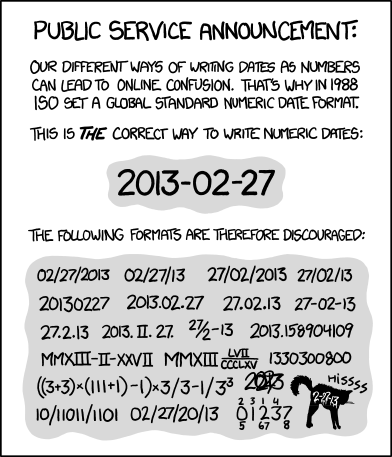

When dates are involved it is important to name the format related to the date. Otherwise it is not clear how to process the data. Most meta data standards desribe the selectable options quit well, for example DataCite accepts all date formats defined by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Other standards may encourage you to use ISO 8601.

Key dates associated with the data, including:

- project start and end date,

- release date,

- ime period covered by the data,

- and other dates associated with the data lifespan (maintenance cycle, update schedule, etc.).

https://xkcd.com/1179/

There is a lot of other metadata that you could and should collect, such as the languages used in your dataset or the purpose of your data collection. Just fill in the appropriate fields in your chosen standard and you should be good.

A data inventory is a full record of all files contained in your dataset. It records the location and metadata of your files and makes it easier for the viewer to narrow down which files are relevant to them. [2]

For small projects, a fully fleshed out data inventory may not be necessary. Instead, a spreadsheet or a readme file explaining your data structure may suffice. Larger projects, however, may use databases for their inventories.

Compiling the metadata for your data inventory can be done in different ways depending on the size and/or organisation of your project: You can delegate the responsibility of adding metadata to the creators or owners of each dataset, conduct surveys and interviews with them, or create an automated process that prompts data creators to add their own metadata. Make sure to adhere to any metadata standards you are using. Also, be careful about the information you are sharing publicly and follow privacy guidelines. [3]

When publishing your data, it is important that fellow researchers can actually view it. The best course of action to achieve this is to use open file formats or file formats that are widely adopted to the point of being a standard.

For images, this is usually pretty easy, as the most commonly used formats like JPEG and PNG are already open standards. Video codecs sometimes are not open but will still be recognized by commonly available programs.

When sharing datasets though, this may be a bit more complicated. Consider the following scenario: Your institution bought an expensive software. You are using this software to edit your data. The program offers a proprietary file format to store the data. However, a fellow researcher may not have the means to buy a license for the software. The version you are using may also become outdated and no longer available. Due to the proprietary nature of the file format, the researcher cannot view the data in any other way.

In order to prevent this, convert your data files to an open format after you finished working on them. If no suitable format exists, create your own format but remember to document it properly so that other researchers know how to read or open it.

Also, do not reinvent the wheel: Chances are, a file format capable of storing your data already exists. Use it instead of creating your own.

If there is no way around storing the data in a proprietary format, document the programs and versions used to access the data (see also provenance). When legally possible, you can also supply a build of the software you used along with the data.

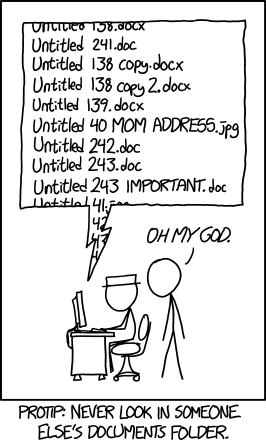

Develop a naming scheme right at the beginning of your project. Stay consistent, if you change your naming scheme, adapt the changes everywhere, even old files.

Also, observe some guidelines on formatting your file names so as to achieve good readability by humans as well as machines:

- Avoid spaces.

- Seperate words by using underscores or use CamelCase.

- Very long names are problematic for certain software, so avoid.

- Use leading zeros for sequential numbering.

It is also a good idea to include the date in a sensible format and to use some organisational elements for fast identification such as short names for locations. Compare to [4],[5],[1].

https://xkcd.com/1459/

You and others should know where your data came from. It is very important to document everything that happened to your data starting from the beginning. Who generated your data? How was it collected? Which software did you use to process and how did you process it? Is it all your own work or did you reuse already published data... These questions and more should be answered as part of your data's provenance [6].

It is very important to keep track of all the steps used to process raw data. You should add information about the pipeline used to create your dataset and be as specific as possible. This information can consist of formulae, algorithm, experimental protocols or other things one might include in a lab notebook. Instead of just writing everything down, you could also use scripts that do all the necessary changes for you. This is especially useful if you need to process lots of similar data. You might also consider using data-cleaning tools such as OpenRefine, which will, amongst other things, automatically keep track of your changes. Another option are electronic lab notebooks (ELN) such as the open source tool eLabFTW. If neither of this options suits you, you could write log messages or keep track of the changes in a README. Make sure to use version control, especially for files that you edit manually. When describing the software you used, include the environment, where this software was running on and the version number of the software and operating system. Same for your hardware or equipment in general, add model and version numbers. This will help to re-create your pipeline if necessary.

As already mentioned in the previous paragraph it is very important to know where your data came from. If you change anything in your project, make sure to include version numbers. If you can, use a version control software like git, it will almost always make your life easier. There are some things that should not be put under version control though: Binary files, large data files or results and your raw data. Your should always keep a copy of your raw data and leave it exactly in that state!

As part of data provenance, researchers need to be able to know where your data came from. This includes giving information where you sourced pre-existing data from. [6] Citing your sources may also be a legal requirement, depending on the license of the work you are citing. When citing, try to stick to a consistent citation style. Check with people in your field which style to use but use it consistently. It is also a good idea to make sure that your sources stay accessible long after publication. Including a DOI, when available, will guarantee permanent access to the cited resource. Otherwise, using web archive sites to capture persistent "snapshots" of webpages can also be an option. Popular providers are archive.today as well as Wayback Machine. The generated links can then be included with your citations.

There are many tools, that can help you in capturing your data's provenance. ProvBook for example, captures the provenance of Jupyter Notebook executions and is also helpful in analysing differences of several runs. Another option is noWorkflow which is aimed at capturing provenance of python scripts. Another option are Scientific Workflow Management Systems (SwfMS). With them you can compose and execute workflows. Examples you could try are VisTrails or Parsl.

Persistent identifiers (PIDs) are used when citing and managing datasets and information. PIDs can be used in many cases. You could use one for your whole project, as PIDs can identify citable online resources, such as datasets or publications, by providing a permanent link to them. Even if the datasets location in the internet changes, the identifier remains the same and will still link to the data, regardless of the new location. Some examples of commonly used persistent identifiers are Digital Object Identifier (DOI) and Uniform Resource Name (URN). But keep in mind, PID is always a promise that the underlying data will never change. If it's necessary to make changes use a new PID and refer to the original dataset. There are also persistent identifiers for people such as ORCID. Sometimes people change their names, move to a different location etc.. A persistent identifier will stay the same nonetheless, so it is also a good idea to mention PIDs of the people that worked on the project.

When opening your project or data to the public, it is important to choose a license. This does not only apply to software projects but really to all kinds of data as well. Without a license, colleagues viewing your publication will not know what they are allowed to with your data and what they are not.

If publishing in a journals, there may by restrictions on what licenses you are allowed to use so make sure to check with your publisher first.

Licensing may also be a factor when applying the FAIR data principles: To meet the R (Reusable) criteria your (meta)data have to be released with a clear and accessible data usage license. The protocol you are using should also be open, free and universally implementable so make sure you read the licenses of any component you are using as well. Licensing also makes sure that researchers re-using your data know how to cite you, an important aspect of data provenance in FAIR data [7].

A very popular choice are the Creative Commons licenses (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/). They allow control of what can be done with your data.

If you are working on a software project, the MIT license is a very clear, permissive license. The GNU General Public License is also a very popular choice amongst open-source software projects.

If you are still unsure, there are good resources to learn about and choose the correct license for your publication like https://choosealicense.com/.

[1] https://library.stanford.edu/research/data-management-services/data-best-practices

[2] https://labs.centerforgov.org/data-governance/data-inventory/

[3] https://doi.org/10.21955/gatesopenres.1114885.1

[4] https://managing-qualitative-data.org/modules/2/c/

[5] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270061735_Nine_simple_ways_to_make_it_easier_to_reuse_your_data

[6] https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/r1-2-metadata-associated-detailed-provenance/

[7] https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/r1-1-metadata-released-clear-accessible-data-usage-license/