Note: I see quite a lot of people still visiting this repo. Note that I haven't kept up-to-date on Electron lately and some things may be outdated.

Electron is a framework for creating native desktop applications with web technologies like JavaScript. It allows you to distribute a web application packaged together with its custom instance of the Chromium browser and, like NodeJS, with better access to the client's OS. You can build an entire desktop application in Javascript.

This makes things easier in a lot of ways. The Javascript-ecosystem is probably the most active one today, with the most programmers, contributors, and open-source resources which gives anyone who decides to go with JS some kind of an edge. JS is additionally easier to learn for beginners or developers with only front-end experience.

However, having desktop applications completely built-in JS can be problematic as well. It makes things very easy for a malicious party who would want to tamper with the source code. Of course, this is still occurring with apps written in other languages, but with JS, malicious parties don't even have to consider the barrier to entry of reverse engineering binaries or bytecode.

Here's the deal:

Each Electron-based application has the same foundation. The root directory holds Electron's prebuilt binaries (IE, the Chromium, and NodeJS engine).

/electron-app/ <-- root

The files located in the root directory are generally uninteresting since they are by no means unique to the application under the spying glass. Where we'll want to look is in the /resources subdirectory, which is where any application-unique or proprietary code is likely to rest.

/electron-app/resources

When you visit this subdirectory you will face two possible scenarios:

- You will see a directory named

app. In that case, it's just a matter of entering it and you'll access all of the application's Javascript-code right away. - You will see a file named

app.asar(or anything with the suffix.asar). This is Electron's idea of avoiding exposing an app's source code. Lucky for you, it's not a problem.

If you end up facing an asar-file, you should know it's just Electron's format for archiving files together in a tar-like way. Files within the archive can be accessed by Electron individually at will. The source code is located in the archive, and it's just a matter of unpacking it:

npx asar extract app.asar folder_for_unpacked

You now have access to the source code in /folder_for_unpacked. The interesting part is that you can now make tiny changes to the source code, pack it back into an .asar archive and replace the old app.asar with it. And when you run the application again, it will work just like normal -- if you haven't introduced any breaking code.

You can't fault Electron or any developers working with it for that. It is just the way this works.

The problem is that, as far as I know, there is currently no standard way of verifying the integrity of these applications. Bad guys are capable of tampering with the source code, but we should at least have the ability to ensure they're not messing around with us.

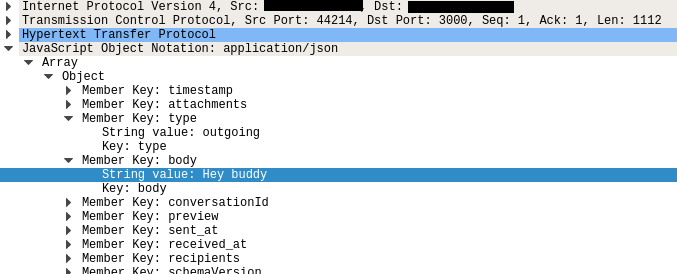

For example, I was able to unpack the source code for the excellent Signal desktop app, modify it to fetch all plaintext messages in the client's decrypted SQLite-database, and post them to a server in my control, pack the code back and replace the original app.asar with it. No user would possibly notice it unless they were overwatching the network traffic for abnormal activities:

Signal does things right by installing the application as root, leaving only superusers with write privileges. However, not all Electron-based applications do this, and even then, they are all possibly vulnerable MITM-attacks where someone intercepts the download of an application with their own, tampered-with version. On Windows and Mac, code signing solutions exist, but they incur an annual fee, and none is available to Linux-based systems.

Due to the increased adoption of Electron-based desktop applications, there really should exist a solution to make application tampering harder. Some very serious organizations trust and rely on Electron-based applications, for example, the European Commission has told its staff to start using Signal, which means we will have to do something about this and until then keep this in the backs of our minds.