life

the self-programming game of life. or splife.

familiarity with conway's game of life is expected for the reader of this document, so let me give you some.

in conway's game of life, the rule set for each cell is fixed:

- any live cell with fewer than two live neighbours dies, as if caused by under-population.

- any live cell with two or three live neighbours lives on to the next generation.

- any live cell with more than three live neighbours dies, as if by overcrowding.

- any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes a live cell, as if by reproduction.

in variations on conway's game, the rule set is parameterized (in one way or another). here he is in his own words.

numberphile: inventing the game of life (john conway)

when asked, has the game of life been built upon, conway replies:

no, it's finished. ... you can build upon it in the following sense: you can study particular configurations, you can find alternative rules that still have the same properties and so on, but, nothing, i think, that followed on it was just as interesting as the basic fact that this set of rules did exist, fairly simple, and have these astonishing properties.

after several years of researching variations, and thinking on the design presented here, i must now disagree: i think this family of state machines is still quite interesting. here is why.

in splife, when each cell is processed, the rules for whether that cell lives or dies are expressed as a program that is systematically derived from the state of the other nearby grid cells. thus each cell's future is determined by its "neighborhood" during that iteration, and the rules will be different on the next iteration.

most initial machine states die (hypothetically). but those that live, perhaps even grow, are self-editing programs.

Machine Description

as in traditional life, every cell within the grid is visited, the next state for that cell calculated and set aside temporarily, and then the old grid replaced with the new grid when all cells have been visited. also, the extents of the grid grow organically to accomodate every birth in each of the four cardinal directions. and, your favored memory representation of choice will work: typically rows count from zero at the top towards the bottom, and columns from zero on the left towards the right.

when a cell is visited, the machine must read the surrounding program to get the set of rules for that cell.

each cell is one bit. instruction words are one byte.

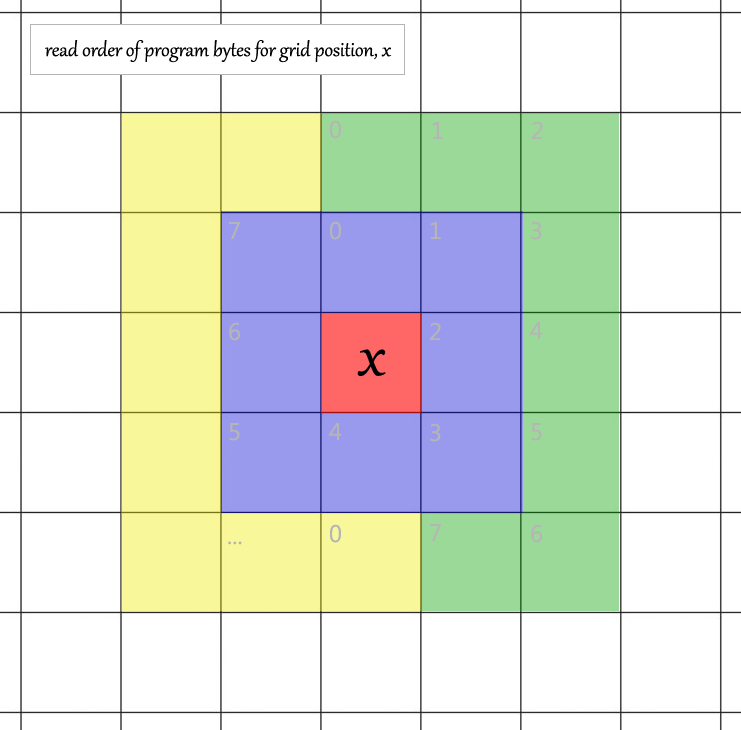

program read order is clockwise starting at "top dead center" or "above" the cell. the reader begins on the row containing this location, and it spirals outward to each successive "ring" of cells.

in this illustration and in the rest of this document the current cell is referred to as x:

cell x is encircled by three bytes of code: blue, green, and yellow, in that order. the astute reader will note that each ring contains exactly one more byte than the last.

as in virtually all other game-of-life variations, the current maximum/minimum extents of the living cells in the grid define the boundary of the grid, thus what cells are processed, thus how many programs are run for a single generation. addressing within a program is done relative to the cell being processed, so as to circumvent the issue of renumbering memory addresses from a "true zero", typically the top left corner, whenever the grid expands/contracts.

the machine does not have a stack or heap. the grid state is self-evident, and it is its own program code, but nothing else. i guess that might be interesting to look into, with a bigger word size, but first... read on.

Registers

the splife machine offers two registers to a program.

Rr

the result register. stores only one bit of information. initialized to zero at the beginning of each program (each cell), and always written back to that cell when RET is executed. written to by a compare instruction.

Rc

the counter register. stores three bits of information. initialized to zero at the beginning of each program. read by compare and conditional jump instructions, written to by a load instruction.

Instructions

bitmasks for each instruction below describe which bits must be set to 1 or 0 and which are operands. when an operand

exists for an instruction, it is named with one letter, but that letter is repeated in the mask to demonstrate width

in bits of the value. for example, a function code f that is three bits is documented as fff.

the first two bits of each instruction word indicate what will be executed, with the exception of the RET and

unconditional JUMP instructions, which share the prefix bits 00. thus, there are five instructions.

RETURN (RET)

00000000

program read stops. the program is over.

- the current value of the result register

Rris written to cell position x. - lone cells die: this is their first/only instruction read (consistent with conway)

- no matter how big the grid is, the machine will inevitably find a return instruction.

JUMP (JMP)

00 kkkkkk

jump the next k instructions and resume execution

kis a 6-bit, unsigned integer greater than zero (if zero, that would just be RET)- if

kindicates a location that starts outside the grid, and stays outside the grid, this instruction may be optimized to a RET.

CONDITIONAL JUMP (CJMP)

01 kkkkkk

jump to the next kth instruction if Rc is nonzero. resume read/execution there.

kis a 6-bit, unsigned integer.- if

kindicates a location that starts outside the grid, and stays outside the grid, this instruction may be optimized to a RET. - the machine simply updates its PCI with

kand continues, which meansk=1is the equivalent of a NOP instruction, as the PCI defaults to 1 at the start of each new program execution anyway.

COMPARE (CMP)

10 fff kkk

compare the counter register Rc (LHS) to a constant value k (RHS)

fdefines the comparison operator:100equal010less-than110less-than-or-equal001greater-than101greater-than-or-equal000false111true011not-equal

kis a 3-bit, unsigned integer- store the result to the result register,

Rr - if the result is true then store 1, otherwise 0

LOAD-INCREMENT (LOI)

11 uu ii jj

reads a neighbor of x at row offset i and column offset j

- if the cell at offset

i,jfrom x is live, then add 1 to the counter registerRc iandjare 2-bit, one's complement integers:00zero01one (e.g. right or down)10negative one (e.g. left or up)11negative zero. same as zero.

- whenever 1 is added to

Rcand it was already at its max value of seven,Rcoverflows to zero. - there is no overflow flag.

- the second bit pair

uis ignored. this should be considered an undefined region. a future implementation may require thatube00to execute the LOI instruction.

Implementation Detail

spiraling outward from x? how does the program counter work?

starting at the i,j where x is found, the PC is set one row above, then N instructions are read in a certain square clockwise pattern of a certain width, and then the process is repeated for N+1. said pattern is contingent on N. thus a vector of moves can be deduced for each instruction, and there are eight such moves per instruction, every time.

before the machine executes a program it sets its internal program counter increment (PCI) to 1. the jump instructions are allowed to change this value, but then it will be reset to 1 before the next instruction executes. i don't consider it a register because it shouldn't be directly exposed to the program, and, future versions of this machine could introduce levels of detail that real, early architectures have had which make branching more indirect/relative, and we still want to be talking rationally about "the program counter" in that scenario, where the arguments to a branch or jump are far removed from the actual change effected on the PC.

one could use a bit of math to skip ahead rather than calculate every vector when jumping... i think.

are off-grid cells dead? can i stop reading when i reach the edge?

like traditional life, reading cells off-grid is done by calling those locations dead, and not accessing what would be invalid memory. as can be seen in the read order illustration, it is possible in smaller grids to go beyond the extents of the acutal underlying memory and/or of the grid virtually superimposed on said memory, within the read of a single instruction word. for example, to the right when reading the first or second byte at bits 1 and 2, respectively. and it is possible even to come back into the grid again for example when moving left to read bit 4 of byte 1 or bit 7 of byte 2.

thus it is important not to short-circuit this read loop when leaving the grid. always collect all eight cells of each instruction vector, just don't read any memory when the coordinate is off-grid. unlike traditional life, you are not simply counting neighbors, you are placing bits in a specific position within a byte.

how many instructions will be read, and can they be fetched in advance of execution?

the fetch cycle stops when it finds a RET, however, the astute reader of this document will have noted that either jump instruction could send the fetcher beyond the RET that it is imminently headed for. while this is so, the range of values that can be jumped to are constrained, and the operand is an immediate constant, not a variable read from the program. thus, the fetch cycle can be completed prior to the execution of any instruction, for any cell.

why does unconditional JUMP with a range of 0 overlap with RET?

this simplifies execution greatly. the JUMP operand can simply move to the program counter increment that would already be used, and which would default to 1 inside the machine. were you to overwrite PCI with 0, you would not increment the program counter, fetch your JUMP 0 again, and execute it again, resulting in an infinite loop. this is the logical equivalent of never processing again, therefore, RET is the perfect instruction with which to overlap.

i see some bias in how patterns influence the "drift" of live cells in the grid due to the choices made that define any or all of these instructions.

me too.

you execute a different program for each cell because of the relative positions in the machine fetch algorithm. suppose instead you were to find the extents of the whole grid, read it as just one program, and then execute that program on each cell?

indeed.