I demonstrate a proof of concept execution of Smart Contracts on Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) written in Prolog.

Prolog is a very high level programming language. It stands for PROgramming in LOGic. It has built-on non-determinism, and and it searches for the solution. The final execution trace containing no non-determinism is committed as a Stark proof, sent on-chain to be verified by the Stark verifier, along with the execution results as state transitions, so Smart Contracts can be effectively executed in Prolog.

This system would allow for great efficiency, as the non-deterministic execution (search) is performed off-chain. In addition, the Stark proof size is poly-log of of the execution trace, further compressing the proof. Finally, combining multiple proofs in the Starkware SHARP reduces the effective proof size even further, so on-chain execution only needs recording of the state changes in addition.

Prolog is a declarative language. In it, for example, we can define:

grandparent(A, C) :- parent(A, B), parent(B, C).

parent(adam, seth).

parent(seth, enosh).

parent(adam, cain).

We can ask:

?- grandparent(X, enosh).

And it will respond with:

X = adam

It would be very convenient to be able to execute a smart contract function call in Prolog:

p(Old_state, New_state).

Then submit the (part of) state change on-chain, after verifying the cryptographic proof that the program executed correctly and produced the state change.

Kowalski (Kowalski, Robert. “Logic for Problem Solving.” Elsevier Science Ltd, 1979) has shown that any first order logic statement can be expressed as a set of so called Horn Clauses of the form, for example:

p(A), q(A, B) :- r(A, B, C), s(B).

Each such Horn Clause can be translated into the usual logic symbolic:

or

Variables such as

grandparent(A, C) :- parent(A, B), parent(B, C).

parent(adam, seth).

parent(seth, enosh).

parent(adam, cain).

would mean:

The proof (execution trace of the proof) of a query, for example ?- grandparent(X, enosh)., meaning "find X, such that, :- grandparent(X, enosh) or

Note that the variables can be bound to constant values or functors, such as

The difficulty of deriving the proof in general Horn Clauses is

mitigated in Prolog by allowing only one predicate on the left side. For example a(X), b(X) :- c(X), d(X). is a Horn Clause, but it is not valid in Prolog because on the left side we have two predicates, a and b. This allows Prolog to search for solutions in a depth-first manner.

However, in Prolog, a "dirty" Horn Clause can be written as:

a(X) :- b(X), !, fail.

which means "try to find solution for b(X) and if successful, assume

The Prolog program can be saved in a file, from which we can read it:

?- consult('myprogram.pl').

Then we can ask a query such as:

?- grandparent(X, enosh).

(but in practice, for on-chain execution, this would be myprogram(Oldstate, Newstate)).

and it would respond with:

X = adam

Then we can ask:

?- generateProver(grandparent/2, 'myprogram.cairo').

which would generate the Cairo program that can accept [no] input and return the value of X. This is not very readable, but it compiles and runs using:

scarb cairo-run

which would produce the output "adam", but also produce a Stark proof of the Prolog execution trace and the resulting output.

Finally (in the future), this proof can be submitted to SHARP, which would produce a combined proof and a commitment of the value "adam" on-chain as state change, governed by the verification of that proof.

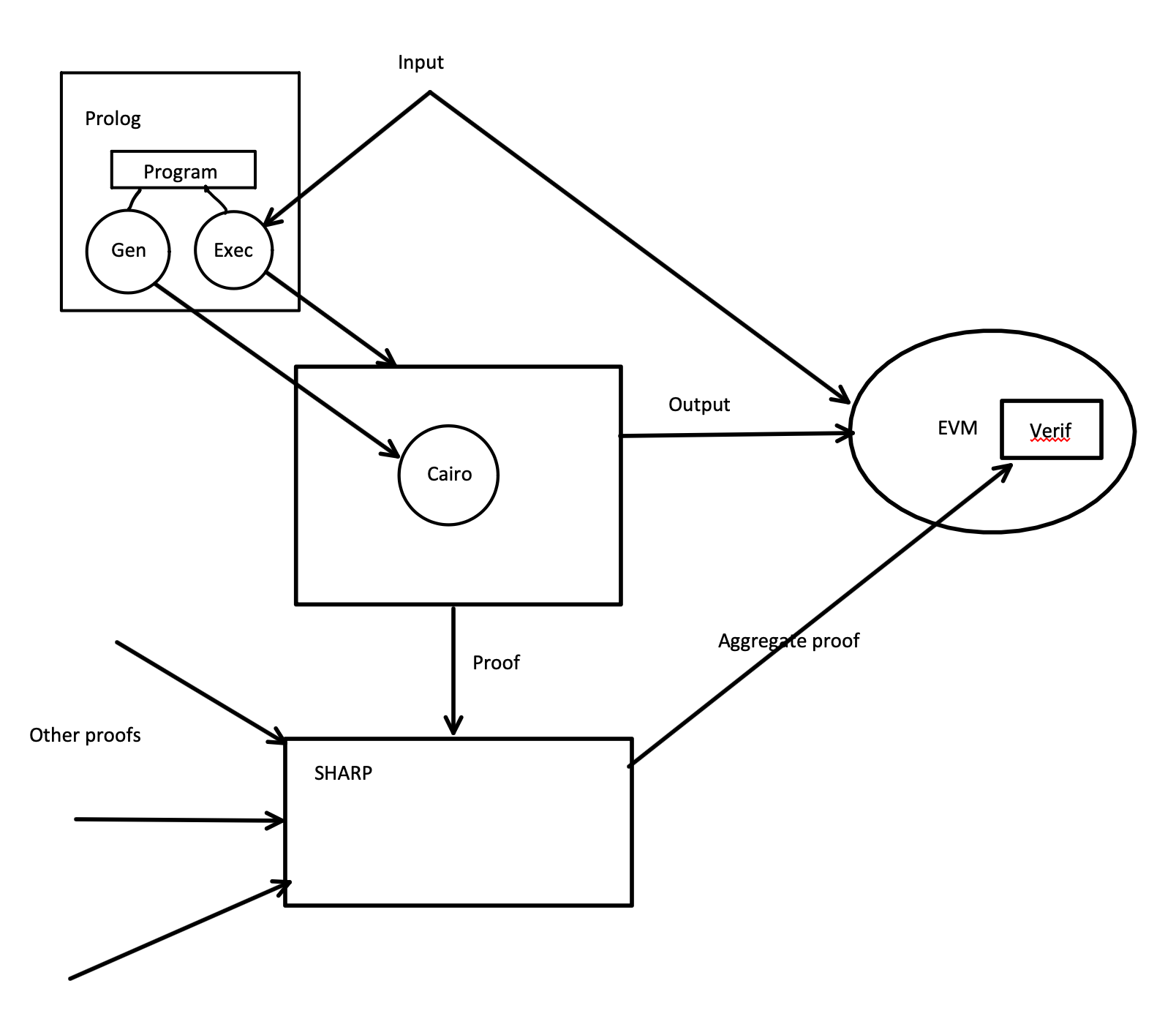

Here is the architecture diagram:

- The Prolog program is written by the application developer.

- In Prolog the ProofGen program in Prolog generates a Cairo program for proving the execution trace.

- The ProofExec program in Prolog runs the application program, produces the execution trace and sends it to the Cairo Prover program.

- The Cairo prover program creates a proof that is sent to SHARP (alternatively, the program itself is sent to SHARP).

- SHARP recursively aggregates all proofs for on-chain verification.

- The Input, Output and the Aggregate Proof are sent to the EVM for verification and state update.

The Prolog program executes and generates an execution trace. This trace contains a list of Clause identifiers (indices in the program) and their variable bindings.

The program, which is a list of clauses is known to the verifier. To convince the verifier that the execution is correct, the following algorithm is executed:

Push the query into the Stack.

for clause in executionTrace {

match the top of the Stack against the clause using the corresponding bindings or return failure

replace the bound tail of the clause at the top of the Stack (BTW the tail may be empty)

if the Stack is empty, return success

}

The bindings to the query determine the values of its variables. This may be confusing, but when proving a relationship, the distinction between input and output is blurred, as all values in the bindings are inputs to the verifier.

Note that the bindings are local to each clause, so each item in the execution trace contains an index to the clause to be matched and a list of bindings for each variable in the clause, as the variables have to be enumerated from 0 to n, the number of variables.

!!!TBD

The Prolog program has a constant number

By the way, even if the proof size of some program that executes in non-deterministic polynomial time

The execution trace, which in itself is a proof is then further compressed to a Stark proof of size

This proof then can be further recursively compressed by SHARP by combining it with other proofs and effectively made even smaller, conceivably down to constant size (I am not completely sure of this, but converting it to SNARK certainly cuts it down to constant size).

The Cairo program re-executes the Prolog execution trace. It can produce Stark proofs from that, as this is the main purpose of Cairo's existence.

The generated Stark proof can be too big to include on-chain on Starknet. For this reason we shall submit it to SHARP (off-chain Cairo execution and proof generation), which regardless of the size will produce the proof and then recursively compose it with other proofs, reducing the proof size from

We have ignored the "dirty" Prolog statements, as we do not have a solution for them. But this is not a tragedy - we can use pure Horn Clauses.

Instead of Prolog, the program should be replaced by pure Horn Clauses. The Stark proofs become complete, but finding the proof becomes more difficult. We don't care - that is off-chain work.