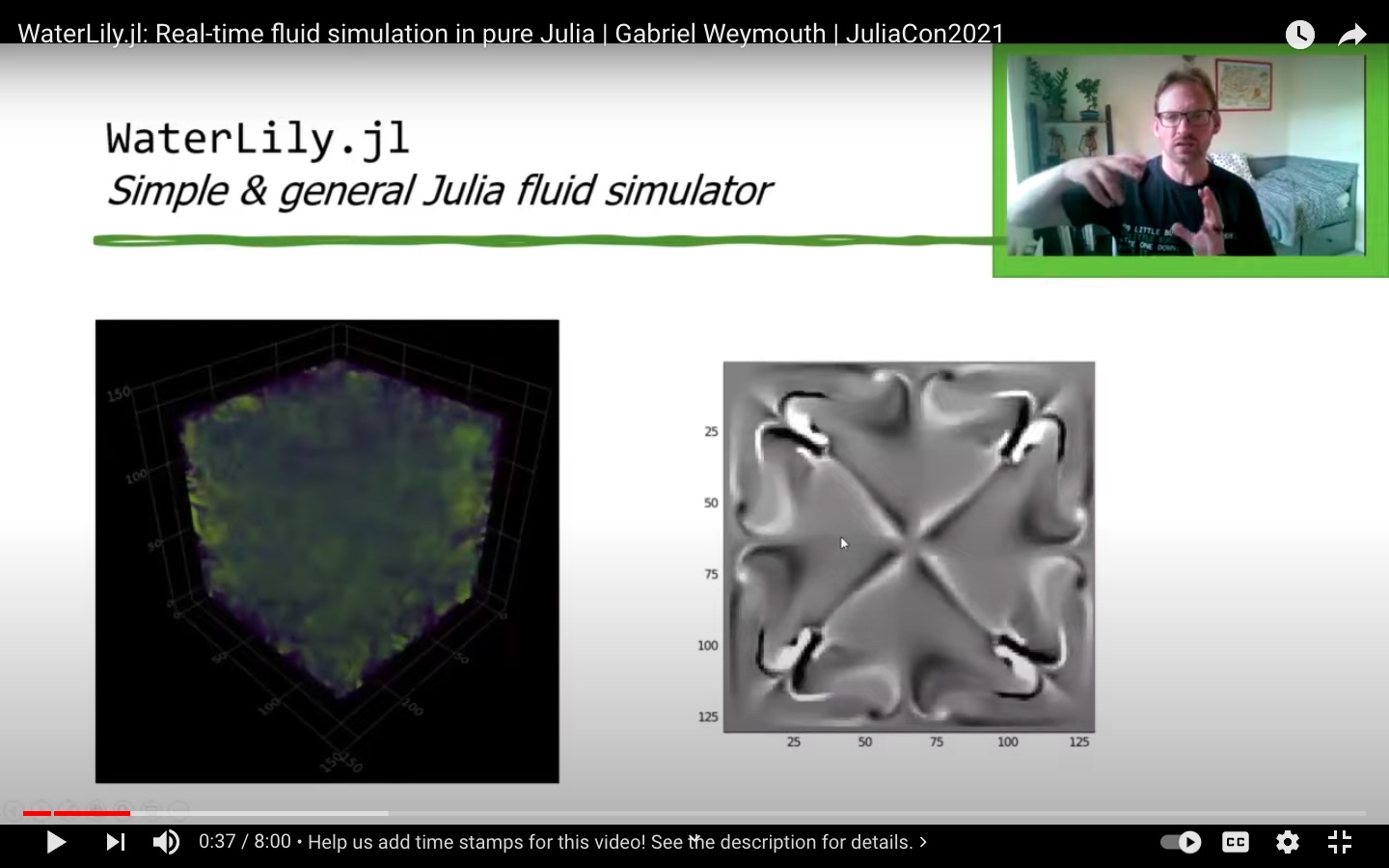

WaterLily.jl is a simple and fast fluid simulator written in pure Julia. This is an experimental project to take advantage of the active scientific community in Julia to accelerate and enhance fluid simulations. Watch the JuliaCon2021 talk here:

WaterLily.jl solves the unsteady incompressible 2D or 3D Navier-Stokes equations on a Cartesian grid. The pressure Poisson equation is solved with a geometric multigrid method. Solid boundaries are modelled using the Boundary Data Immersion Method.

The user can set the boundary conditions, the initial velocity field, the fluid viscosity (which determines the Reynolds number), and immerse solid obstacles using a signed distance function. These examples and others are found in the examples.

We define the size of the simulation domain as nxm cells. The circle has radius R=m/8 and is centered at [m/2,m/2]. The flow boundary conditions are [U=1,0] and Reynolds number is Re=UR/ν where ν (Greek "nu" U+03BD, not Latin lowercase "v") is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid.

using WaterLily

using LinearAlgebra: norm2

function circle(n,m;Re=250)

# Set physical parameters

U,R,center = 1., m/8., [m/2,m/2]

ν=U*R/Re

@show R,ν

body = AutoBody((x,t)->norm2(x .- center) - R)

Simulation((n+2,m+2), [U,0.], R; ν, body)

endThe second to last line defines the circle geometry using a signed distance function. The AutoBody function uses automatic differentiation to infer the other geometric parameter automatically. Replace the circle's distance function with any other, and now you have the flow around something else... such as a donut, a block or the Julia logo. Finally, the last line defines the Simulation by passing in the dims=(n+2,m+2) and the other parameters we've defined.

Now we can create a simulation (first line) and run it forward in time (third line)

circ = circle(3*2^6,2^7)

t_end = 10

sim_step!(circ,t_end)Note we've set n,m to be multiples of powers of 2, which is important when using the (very fast) Multi-Grid solver. We can now access and plot whatever variables we like. For example, we could print the velocity at I::CartesianIndex using println(circ.flow.u[I]) or plot the whole pressure field using

using Plots

contour(circ.flow.p')A set of flow metric functions have been implemented and the examples use these to make gifs such as the one above.

You can also simulate a nontrivial initial velocity field by passing in a vector function.

function TGV(p=6,Re=1e5)

# Define vortex size, velocity, viscosity

L = 2^p; U = 1; ν = U*L/Re

function uλ(i,vx) # vector function

x,y,z = @. (vx-1.5)*π/L # scaled coordinates

i==1 && return -U*sin(x)*cos(y)*cos(z) # u_x

i==2 && return U*cos(x)*sin(y)*cos(z) # u_y

return 0. # u_z

end

# Initialize simulation

Simulation((L+2,L+2,L+2), zeros(3), L; uλ, ν, U)

endThe velocity field is defined by the vector component i and the 3D position vector vx. We scale the coordinates so the velocity will be zero on the domain boundaries and then check which component is needed and return the correct expression.

You can simulate moving bodies in Waterlily by passing a coordinate map to AutoBody in addition to the sdf.

using LinearAlgebra: norm2

using StaticArrays

function hover(L=2^5;Re=250,U=1,amp=0,thk=1+√2)

# Set viscosity

ν=U*L/Re

@show L,ν

# Create dynamic block geometry

function sdf(x,t)

y = x .- SVector(0.,clamp(x[2],-L/2,L/2))

norm2(y)-thk/2

end

function map(x,t)

α = amp*cos(t*U/L); R = @SMatrix [cos(α) sin(α); -sin(α) cos(α)]

R * (x.-SVector(3L+L*sin(t*U/L)+0.01,4L))

end

body = AutoBody(sdf,map)

Simulation((6L+2,6L+2),zeros(2),L;U,ν,body,ϵ=0.5)

endHow to generate a .gif from this can be seen in the examples folder TwoD_block.jl.

In this example, the sdf function defines a line segment from -L/2 ≤ x[2] ≤ L/2 with a thickness thk. To make the line segment move, we define a coordinate tranformation function map(x,t). In this example, the coordinate x is shifted by (3L,4L) at time t=0, which moves the center of the segment to this point. However, the horizontal shift varies harmonically in time, sweeping the segment left and right during the simulation. The example also rotates the segment using the rotation matrix R = [cos(α) sin(α); -sin(α) cos(α)] where the angle α is also varied harmonically. The combined result is a thin flapping line, similar to a cross-section of a hovering insect wing.

One important thing to note here is the use of StaticArrays to define the sdf and map. This speeds up the simulation since it eliminates allocations at every grid cell and time step.

By default, Julia starts up with a single thread of execution. The number of execution threads is controlled either by using the -t/--threads command line argument or by using the JULIA_NUM_THREADS environment variable. When both are specified, then -t/--threads takes precedence.

So, do this when launching Julia if you want multiple threads:

julia -t auto

(automatically uses the number of threads on your CPU)

If you prefer to use the environment variable you can set it as follows in Bash (Linux/macOS):

export JULIA_NUM_THREADS=1024

C shell on Linux/macOS, CMD on Windows:

set JULIA_NUM_THREADS=4

Powershell on Windows:

$env:JULIA_NUM_THREADS=4

Note that this must be done before starting Julia.

- Immerse obstacles defined by 3D meshes or 2D lines using GeometryBasics.

- GPU acceleration with CUDA.jl.

- Split multigrid method into its own repository, possibly merging with AlgebraicMultigrid or IterativeSolvers.

If you have other suggestions or want to help, please raise an issue on github.