This style guide is different from others you may see, because the focus is centered on readability for print and the web. We created this style guide to keep the code in our books, tutorials, and starter kits nice and consistent — even though we have many different authors working on the books.

Our overarching goals are clarity, consistency and brevity, in that order.

- Correctness

- Page guide

- Naming

- Code Organization

- Spacing

- MARKs in the classes

- Comments

- Classes and Structures

- Function Declarations

- Closure Expressions

- Types

- Functions vs Methods

- Memory Management

- Access Control

- Control Flow

- Golden Path

- Semicolons

- Parentheses

- Organization and Bundle Identifier

- References

Strive to make your code compile without warnings. This rule informs many style decisions such as using #selector types instead of string literals.

Setup page guide in Xcode for 180 symbols. This number is recommended in swiftlint settings. So all code should be inside this page guide.

Descriptive and consistent naming makes software easier to read and understand. Use the Swift naming conventions described in the API Design Guidelines. Some key takeaways include:

- striving for clarity at the call site

- prioritizing clarity over brevity

- using camel case (not snake case)

- using uppercase for types (and protocols), lowercase for everything else

- including all needed words while omitting needless words

- using names based on roles, not types

- sometimes compensating for weak type information

- striving for fluent usage

- beginning factory methods with

make - naming methods for their side effects

- verb methods follow the -ed, -ing rule for the non-mutating version

- noun methods follow the formX rule for the mutating version

- boolean types should read like assertions

- protocols that describe what something is should read as nouns

- protocols that describe a capability should end in -able or -ible

- using terms that don't surprise experts or confuse beginners

- generally avoiding abbreviations

- using precedent for names

- preferring methods and properties to free functions

- casing acronyms and initialisms uniformly up or down

- giving the same base name to methods that share the same meaning

- avoiding overloads on return type

- choosing good parameter names that serve as documentation

- labeling closure and tuple parameters

- taking advantage of default parameters

When referring to methods in prose, being unambiguous is critical. To refer to a method name, use the simplest form possible.

- Write the method name with no parameters. Example: Next, you need to call the method

addTarget. - Write the method name with argument labels. Example: Next, you need to call the method

addTarget(_:action:). - Write the full method name with argument labels and types. Example: Next, you need to call the method

addTarget(_: Any?, action: Selector?).

For the above example using UIGestureRecognizer, 1 is unambiguous and preferred.

Pro Tip: You can use Xcode's jump bar to lookup methods with argument labels.

For boolean variables use auxiliary verb at the beginning.

Preferred:

var isFavoriteCategoryFilled: Bool

var hasRoaming: Bool

var isBlocked: BoolNot Preferred:

var favoriteCategoryFilled: Bool

var roaming: Bool

var blocked: BoolSwift types are automatically namespaced by the module that contains them and you should not add a class prefix such as RW. If two names from different modules collide you can disambiguate by prefixing the type name with the module name. However, only specify the module name when there is possibility for confusion which should be rare.

import SomeModule

let myClass = MyModule.UsefulClass()When creating custom delegate methods, an unnamed first parameter should be the delegate source. (UIKit contains numerous examples of this.)

Preferred:

func namePickerView(_ namePickerView: NamePickerView, didSelectName name: String)

func namePickerViewShouldReload(_ namePickerView: NamePickerView) -> BoolNot Preferred:

func didSelectName(namePicker: NamePickerViewController, name: String)

func namePickerShouldReload() -> BoolUse compiler inferred context to write shorter, clear code. (Also see Type Inference.)

Preferred:

let selector = #selector(viewDidLoad)

view.backgroundColor = .red

let toView = context.view(forKey: .to)

let view = UIView(frame: .zero)Not Preferred:

let selector = #selector(ViewController.viewDidLoad)

view.backgroundColor = UIColor.red

let toView = context.view(forKey: UITransitionContextViewKey.to)

let view = UIView(frame: CGRect.zero)Generic type parameters should be descriptive, upper camel case names. When a type name doesn't have a meaningful relationship or role, use a traditional single uppercase letter such as T, U, or V.

Preferred:

struct Stack<Element> { ... }

func write<Target: OutputStream>(to target: inout Target)

func swap<T>(_ a: inout T, _ b: inout T)Not Preferred:

struct Stack<T> { ... }

func write<target: OutputStream>(to target: inout target)

func swap<Thing>(_ a: inout Thing, _ b: inout Thing)Use US English spelling to match Apple's API.

Preferred:

let color = "red"Not Preferred:

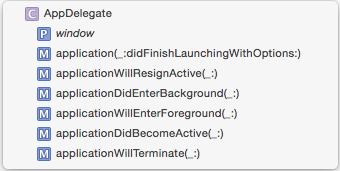

let colour = "red"Use extensions to organize your code into logical blocks of functionality. Each extension should be set off with a // MARK: - comment to keep things well-organized.

The next sequence nice to follow:

// MARK: - Types

// MARK: - Constants

// MARK: - IBOutlet

// MARK: - Public Properties

// MARK: - Private Properties

// MARK: - Initializers

// MARK: - UIViewController(*)

// MARK: - Public methods

// MARK: - IBAction

// MARK: - Private Methods(*)Instead of

UIViewControlleryou must write other superclass, that methods you override.

In particular, when adding protocol conformance to a model, prefer adding a separate extension for the protocol methods. This keeps the related methods grouped together with the protocol and can simplify instructions to add a protocol to a class with its associated methods. We accompany the protocols with MARK. Before extension we put two empty lines.

Preferred:

class MyViewController: UIViewController {

// class stuff here

}

// MARK: - UITableViewDataSource

extension MyViewController: UITableViewDataSource {

// table view data source methods

}

// MARK: - UIScrollViewDelegate

extension MyViewController: UIScrollViewDelegate {

// scroll view delegate methods

}Not Preferred:

class MyViewController: UIViewController, UITableViewDataSource, UIScrollViewDelegate {

// all methods

}This rule doesn't work for two cases:

- When you need override method which implemented in extension (Declarations in extensions cannot override yet)

- When you use class with generic and Objective C protocols with optional methods (@objc is not supported within extensions of generic classes or classes that inherit from generic classes)

Since the compiler does not allow you to re-declare protocol conformance in a derived class, it is not always required to replicate the extension groups of the base class. This is especially true if the derived class is a terminal class and a small number of methods are being overridden. When to preserve the extension groups is left to the discretion of the author.

For UIKit view controllers, consider grouping lifecycle, custom accessors, and IBAction in separate class extensions.

Unused (dead) code, including Xcode template code and placeholder comments should be removed. An exception is when your tutorial or book instructs the user to use the commented code.

Aspirational methods not directly associated with the tutorial whose implementation simply calls the superclass should also be removed. This includes any empty/unused UIApplicationDelegate methods.

Preferred:

override func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, numberOfRowsInSection section: Int) -> Int {

return Database.contacts.count

}Not Preferred:

override func didReceiveMemoryWarning() {

super.didReceiveMemoryWarning()

// Dispose of any resources that can be recreated.

}

override func numberOfSections(in tableView: UITableView) -> Int {

// #warning Incomplete implementation, return the number of sections

return 1

}

override func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, numberOfRowsInSection section: Int) -> Int {

// #warning Incomplete implementation, return the number of rows

return Database.contacts.count

}Keep imports minimal. For example, don't import UIKit when importing Foundation will suffice.

If you want to make your code more understandable, you will separate your class with MARKs. When you make your first MARK after class defenition, you put only one empty string. But after that, when you are putting next MARK, you must separate it with two empty lines.

Example:

Preferred:

class ViewController: UIViewController {

// MARK: - Public Properties

var presenter: ViewControllerOutput?

// MARK: - Private Properties

private let headerView: UIView?

...

}Not Preferred:

class ViewController: UIViewController {

// MARK: - Public Properties

var presenter: ViewControllerOutput?

// MARK: - Private Properties

private let headerView: UIView?

...

}-

Indent using 4 spaces rather than tabs to conserve space and help prevent line wrapping.

-

Method braces and other braces (

if/else/switch/whileetc.) always open on the same line as the statement but close on a new line. -

Tip: You can re-indent by selecting some code (or ⌘A to select all) and then Control-I (or Editor\Structure\Re-Indent in the menu). Some of the Xcode template code will have 4-space tabs hard coded, so this is a good way to fix that.

Preferred:

if user.isHappy {

// Do something

} else {

// Do something else

}Not Preferred:

if user.isHappy

{

// Do something

}

else {

// Do something else

}-

There should be exactly one blank line between methods to aid in visual clarity and organization. Whitespace within methods should separate functionality, but having too many sections in a method often means you should refactor into several methods.

-

Colons always have no space on the left and one space on the right. Exceptions are the ternary operator

? :, empty dictionary[:]and#selectorsyntax for unnamed parameters(_:).

Preferred:

class TestDatabase: Database {

var data: [String: CGFloat] = ["A": 1.2, "B": 3.2]

}Not Preferred:

class TestDatabase : Database {

var data :[String:CGFloat] = ["A" : 1.2, "B":3.2]

}-

Long lines should be wrapped at around 70 characters. A hard limit is intentionally not specified.

-

Avoid trailing whitespaces at the ends of lines.

-

Add a single newline character at the end of each file.

When they are needed, use comments to explain why a particular piece of code does something. Comments must be kept up-to-date or deleted.

Avoid block comments inline with code, as the code should be as self-documenting as possible. Exception: This does not apply to those comments used to generate documentation.

Remember, structs have value semantics. Use structs for things that do not have an identity. An array that contains [a, b, c] is really the same as another array that contains [a, b, c] and they are completely interchangeable. It doesn't matter whether you use the first array or the second, because they represent the exact same thing. That's why arrays are structs.

Classes have reference semantics. Use classes for things that do have an identity or a specific life cycle. You would model a person as a class because two person objects are two different things. Just because two people have the same name and birthdate, doesn't mean they are the same person. But the person's birthdate would be a struct because a date of 3 March 1950 is the same as any other date object for 3 March 1950. The date itself doesn't have an identity.

Sometimes, things should be structs but need to conform to AnyObject or are historically modeled as classes already (NSDate, NSSet). Try to follow these guidelines as closely as possible.

Here's an example of a well-styled class definition:

class Circle: Shape {

var x: Int, y: Int

var radius: Double

var diameter: Double {

get {

return radius * 2

}

set {

radius = newValue / 2

}

}

init(x: Int, y: Int, radius: Double) {

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.radius = radius

}

convenience init(x: Int, y: Int, diameter: Double) {

self.init(x: x, y: y, radius: diameter / 2)

}

override func area() -> Double {

return Double.pi * radius * radius

}

}

extension Circle: CustomStringConvertible {

var description: String {

return "center = \(centerString) area = \(area())"

}

private var centerString: String {

return "(\(x),\(y))"

}

}When the method signature is too long, parameters should be moved to a new line:

override func register(

withСardNumber cardNumber: String,

completion completionBlock: @escaping AuthService.RegisterWithCardNumberCompletionBlock,

failure failureBlock: @escaping Service.ServiceFailureBlock) -> WebTransportOperation {

// reticulate code goes here

}The example above demonstrates the following style guidelines:

- Specify types for properties, variables, constants, argument declarations and other statements with a space after the colon but not before, e.g.

x: Int, andCircle: Shape. - Define multiple variables and structures on a single line if they share a common purpose / context.

- Indent getter and setter definitions and property observers.

- Don't add modifiers such as

internalwhen they're already the default. Similarly, don't repeat the access modifier when overriding a method. - Organize extra functionality (e.g. printing) in extensions.

- Hide non-shared, implementation details such as

centerStringinside the extension usingprivateaccess control.

For conciseness, avoid using self since Swift does not require it to access an object's properties or invoke its methods.

Use self only when required by the compiler (in @escaping closures, or in initializers to disambiguate properties from arguments). In other words, if it compiles without self then omit it.

For conciseness, if a computed property is read-only, omit the get clause. The get clause is required only when a set clause is provided.

Preferred:

var diameter: Double {

return radius * 2

}Not Preferred:

var diameter: Double {

get {

return radius * 2

}

}Always use computed property instead of method with zero arguments and no side effects.

Preferred:

var homeFolderPath: Path {

//...

return path

}Not Preferred:

func homeFolderPath() -> Path {

//...

return path

}Always marking classes or members as final in tutorials can distract from the main topic and is not required. Nevertheless, use of final can sometimes clarify your intent and is worth the cost. In the below example, Box has a particular purpose and customization in a derived class is not intended. Marking it final makes that clear.

// Turn any generic type into a reference type using this Box class.

final class Box<T> {

let value: T

init(_ value: T) {

self.value = value

}

}This is improve yout code reading and speed up compilation.

Keep short function declarations on one line including the opening brace:

func reticulateSplines(spline: [Double]) -> Bool {

// reticulate code goes here

}For functions add line breaks at each argument if it's exceed page guide:

func reticulateSplines(

spline: [Double],

adjustmentFactor: Double,

translateConstant: Int,

comment: String) -> Bool {

// reticulate code goes here

}The same rule applied for function calls.

Leave one empty line between functions and one after MARKs.

func colorView() {

//...

}

func reticulate() {

//...

}

// MARK: - Private

private func retry() {

//...

}Use trailing closure syntax only if there's a single closure expression parameter at the end of the argument list. Give the closure parameters descriptive names.

Closure parameter type and parentheses should be omitted.

Preferred:

UIView.animate(withDuration: 1.0) {

self.myView.alpha = 0

}

UIView.animate(

withDuration: 1.0,

animations: {

self.myView.alpha = 0

},

completion: { finished in

self.myView.removeFromSuperview()

})Not Preferred:

UIView.animate(withDuration: 1.0, animations: {

self.myView.alpha = 0

})

UIView.animate(withDuration: 1.0, animations: {

self.myView.alpha = 0

}) { (f: Bool) in

self.myView.removeFromSuperview()

}For single-expression closures where the context is clear, use implicit returns:

attendeeList.sort { a, b in

a > b

}Chained methods using trailing closures should be clear and easy to read in context. Decisions on spacing, line breaks, and when to use named versus anonymous arguments is left to the discretion of the author. Examples:

let value = numbers

.map {$0 * 2}

.filter {$0 > 50}

.map {$0 + 10}Always use Swift's native types when available. Swift offers bridging to Objective-C so you can still use the full set of methods as needed.

Preferred:

let width: Double = 120 // Double

let widthString = (width as NSNumber).stringValue // StringNot Preferred:

let width: NSNumber = 120.0 // NSNumber

let widthString: NSString = width.stringValue // NSStringIn Sprite Kit code, use CGFloat if it makes the code more succinct by avoiding too many conversions.

Constants are defined using the let keyword, and variables with the var keyword. Always use let instead of var if the value of the variable will not change.

Tip: A good technique is to define everything using let and only change it to var if the compiler complains!

You can define constants on a type rather than on an instance of that type using type properties. To declare a type property as a constant simply use static let. Type properties declared in this way are generally preferred over global constants because they are easier to distinguish from instance properties. Example:

Preferred:

enum Math {

static let e = 2.718281828459045235360287

static let root2 = 1.41421356237309504880168872

}

let hypotenuse = side * Math.root2Note: The advantage of using a case-less enumeration is that it can't accidentally be instantiated and works as a pure namespace.

Not Preferred:

let e = 2.718281828459045235360287 // pollutes global namespace

let root2 = 1.41421356237309504880168872

let hypotenuse = side * root2 // what is root2?In case of declaration of single constant use following names

Preferred:

let TopMargin: CGFloat = 10Not Preferred:

let kTopMargin: CGFloat = 10

let bottomMargin: CGFloat = 100 Static methods and type properties work similarly to global functions and global variables and should be used sparingly. They are useful when functionality is scoped to a particular type or when Objective-C interoperability is required.

Declare variables and function return types as optional with ? where a nil value is acceptable.

Use implicitly unwrapped types declared with ! only for instance variables that you know will be initialized later before use, such as subviews that will be set up in viewDidLoad.

When accessing an optional value, use optional chaining if the value is only accessed once or if there are many optionals in the chain:

self.textContainer?.textLabel?.setNeedsDisplay()Use optional binding when it's more convenient to unwrap once and perform multiple operations:

if let textContainer = self.textContainer {

// do many things with textContainer

}When naming optional variables and properties, avoid naming them like optionalString or maybeView since their optional-ness is already in the type declaration.

For optional binding, shadow the original name when appropriate rather than using names like unwrappedView or actualLabel. Add new line after if, if there are several variables in unwrapping clause.

Preferred:

var subview: UIView?

var volume: Double?

// later on...

if let subview = subview,

let volume = volume {

// do something with unwrapped subview and volume

}Not Preferred:

var optionalSubview: UIView?

var volume: Double?

if let unwrappedSubview = optionalSubview {

if let realVolume = volume {

// do something with unwrappedSubview and realVolume

}

}Consider using lazy initialization for finer grain control over object lifetime. This is especially true for UIViewController that loads views lazily. You can either use a closure that is immediately called { }() or call a private factory method. Example:

lazy var locationManager: CLLocationManager = self.makeLocationManager()

private func makeLocationManager() -> CLLocationManager {

let manager = CLLocationManager()

manager.desiredAccuracy = kCLLocationAccuracyBest

manager.delegate = self

manager.requestAlwaysAuthorization()

return manager

}Notes:

[unowned self]is not required here. A retain cycle is not created.- Location manager has a side-effect for popping up UI to ask the user for permission so fine grain control makes sense here.

Prefer compact code and let the compiler infer the type for constants or variables of single instances. Type inference is also appropriate for small (non-empty) arrays and dictionaries. When required, specify the specific type such as CGFloat or Int16.

Preferred:

let message = "Click the button"

let currentBounds = computeViewBounds()

var names = ["Mic", "Sam", "Christine"]

let maximumWidth: CGFloat = 106.5Not Preferred:

let message: String = "Click the button"

let currentBounds: CGRect = computeViewBounds()

let names = [String]()For empty arrays and dictionaries you should use type annotation.

Preferred:

var names: [String] = []

var lookup: [String: Int] = []Not Preferred:

var names = [String]()

var lookup = [String: Int]()NOTE: Following this guideline means picking descriptive names is even more important than before.

Prefer the shortcut versions of type declarations over the full generics syntax.

Preferred:

var deviceModels: [String]

var employees: [Int: String]

var faxNumber: Int?Not Preferred:

var deviceModels: Array<String>

var employees: Dictionary<Int, String>

var faxNumber: Optional<Int>Use the following carrying when array or dictionary go over page guide.

Preferred:

let deviceModels = ["BMW": 100, "Mercedes": 120]

let wheels = [

"Continental",

"Vitoria",

...

]Not Preferred:

let wheels = ["Continental", "Vitoria", // to many over page guide]Free functions, which aren't attached to a class or type, should be used sparingly. When possible, prefer to use a method instead of a free function. This aids in readability and discoverability.

Free functions are most appropriate when they aren't associated with any particular type or instance.

Preferred

let sorted = items.mergeSorted() // easily discoverable

rocket.launch() // acts on the modelNot Preferred

let sorted = mergeSort(items) // hard to discover

launch(&rocket)Free Function Exceptions

let tuples = zip(a, b) // feels natural as a free function (symmetry)

let value = max(x, y, z) // another free function that feels naturalCode (even non-production, tutorial demo code) should not create reference cycles. Analyze your object graph and prevent strong cycles with weak and unowned references. Alternatively, use value types (struct, enum) to prevent cycles altogether.

Extend object lifetime using the [weak self] and guard let `self` = self else { return } idiom. [weak self] is preferred to [unowned self] where it is not immediately obvious that self outlives the closure. Explicitly extending lifetime is preferred to optional unwrapping.

Preferred

resource.request().onComplete { [weak self] response in

guard let `self` = self else { return }

let model = strongSelf.updateModel(response)

strongSelf.updateUI(model)

}Not Preferred

// might crash if self is released before response returns

resource.request().onComplete { [unowned self] response in

let model = self.updateModel(response)

self.updateUI(model)

}Not Preferred

// deallocate could happen between updating the model and updating UI

resource.request().onComplete { [weak self] response in

let model = self?.updateModel(response)

self?.updateUI(model)

}Full access control annotation in tutorials can distract from the main topic and is not required. Using private and fileprivate appropriately, however, adds clarity and promotes encapsulation. Prefer private to fileprivate when possible. Using extensions may require you to use fileprivate.

Only explicitly use open, public, and internal when you require a full access control specification.

Use access control as the leading property specifier. The only things that should come before access control are the static specifier or attributes such as @IBAction, @IBOutlet and @discardableResult.

Preferred:

private let message = "Great Scott!"

class TimeMachine {

fileprivate dynamic lazy var fluxCapacitor = FluxCapacitor()

}Not Preferred:

fileprivate let message = "Great Scott!"

class TimeMachine {

lazy dynamic fileprivate var fluxCapacitor = FluxCapacitor()

}Prefer the for-in style of for loop over the while-condition-increment style.

Preferred:

for _ in 0..<3 {

print("Hello three times")

}

for (index, person) in attendeeList.enumerated() {

print("\(person) is at position #\(index)")

}

for index in stride(from: 0, to: items.count, by: 2) {

print(index)

}

for index in (0...3).reversed() {

print(index)

}Not Preferred:

var i = 0

while i < 3 {

print("Hello three times")

i += 1

}

var i = 0

while i < attendeeList.count {

let person = attendeeList[i]

print("\(person) is at position #\(i)")

i += 1

}When coding with conditionals, the left-hand margin of the code should be the "golden" or "happy" path. That is, don't nest if statements. Multiple return statements are OK. The guard statement is built for this.

Preferred:

func computeFFT(context: Context?, inputData: InputData?) throws -> Frequencies {

guard let context = context

else {

throw FFTError.noContext

}

guard let inputData = inputData

else {

throw FFTError.noInputData

}

// use context and input to compute the frequencies

return frequencies

}Not Preferred:

func computeFFT(context: Context?, inputData: InputData?) throws -> Frequencies {

if let context = context {

if let inputData = inputData {

// use context and input to compute the frequencies

return frequencies

} else {

throw FFTError.noInputData

}

} else {

throw FFTError.noContext

}

}When multiple conditionals are inside the operator, add line breaks before a new operand. Extract difficult conditions to functions.

Preferred:

if isTrue(),

isFalse(),

tax > MinTax {

// ...

}Not Preferred:

if a > b && b > c && tax > MinTax && currentValue > MaxValue {

// ...

}When multiple optionals are unwrapped either with guard or if let, minimize nesting by using the compound version when possible. Example:

Preferred:

guard

let number1 = number1,

let number2 = number2,

let number3 = number3

else {

fatalError("impossible")

}

// do something with numbersor you can use one-liner with one else operation

guard

let number1 = number1,

let number2 = number2

else { return }

// do something with numbersor one-liner with one let operation

guard let number1 = number1 else { return }Not Preferred:

if let number1 = number1 {

if let number2 = number2 {

if let number3 = number3 {

// do something with numbers

} else {

fatalError("impossible")

}

} else {

fatalError("impossible")

}

} else {

fatalError("impossible")

}Guard statements are required to exit in some way. Generally, this should be simple one line statement such as return, throw, break, continue, and fatalError(). Large code blocks should be avoided. If cleanup code is required for multiple exit points, consider using a defer block to avoid cleanup code duplication.

Swift does not require a semicolon after each statement in your code. They are only required if you wish to combine multiple statements on a single line.

Do not write multiple statements on a single line separated with semicolons.

Preferred:

let swift = "not a scripting language"Not Preferred:

let swift = "not a scripting language";NOTE: Swift is very different from JavaScript, where omitting semicolons is generally considered unsafe

Parentheses around conditionals are not required and should be omitted.

Preferred:

if name == "Hello" {

print("World")

}Not Preferred:

if (name == "Hello") {

print("World")

}In larger expressions, optional parentheses can sometimes make code read more clearly.

Preferred:

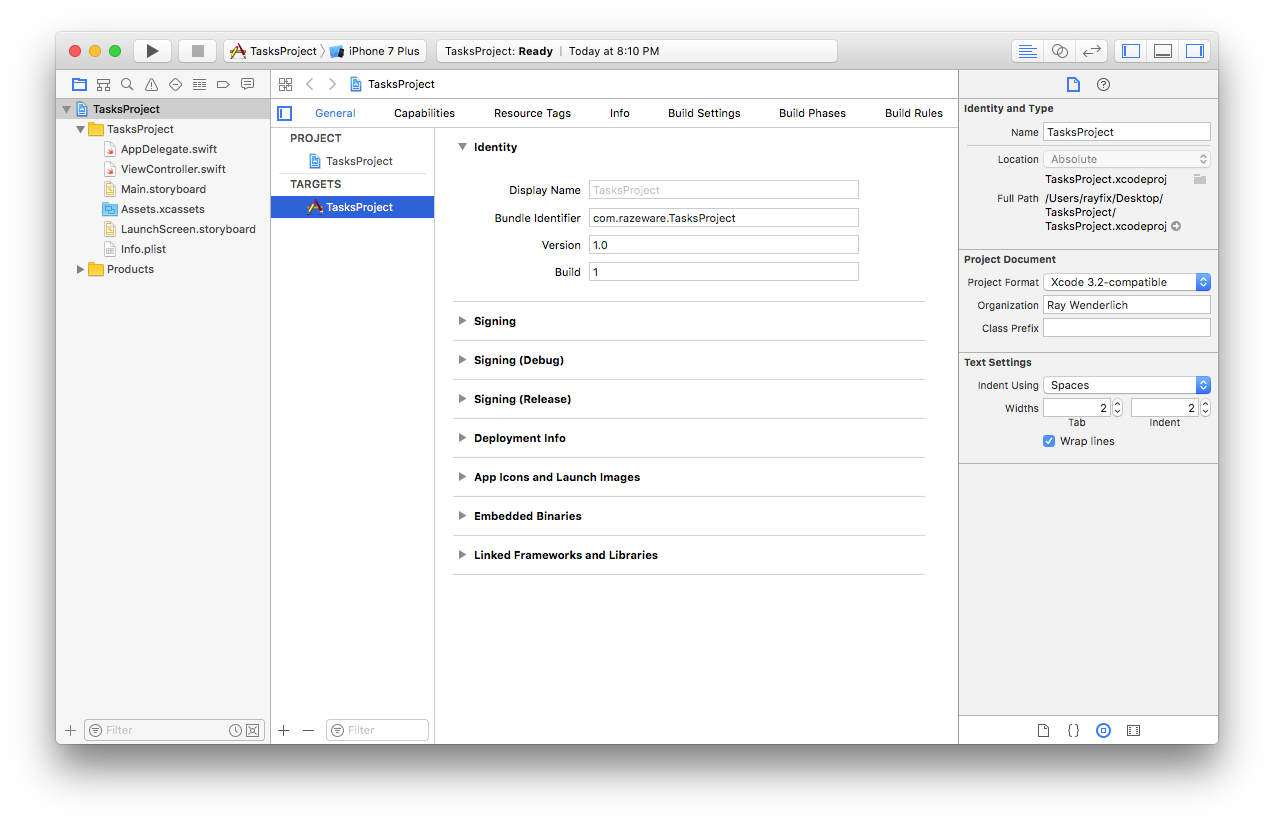

let playerMark = (player == current ? "X" : "O")Where an Xcode project is involved, the organization should be set to Ray Wenderlich and the Bundle Identifier set to com.razeware.TutorialName where TutorialName is the name of the tutorial project.