- The develop branch is getting stable

- All networking in develop is moved to a separate Service

This is an ambitious example project of what can be done with RxJava to create an app based on streams of data.

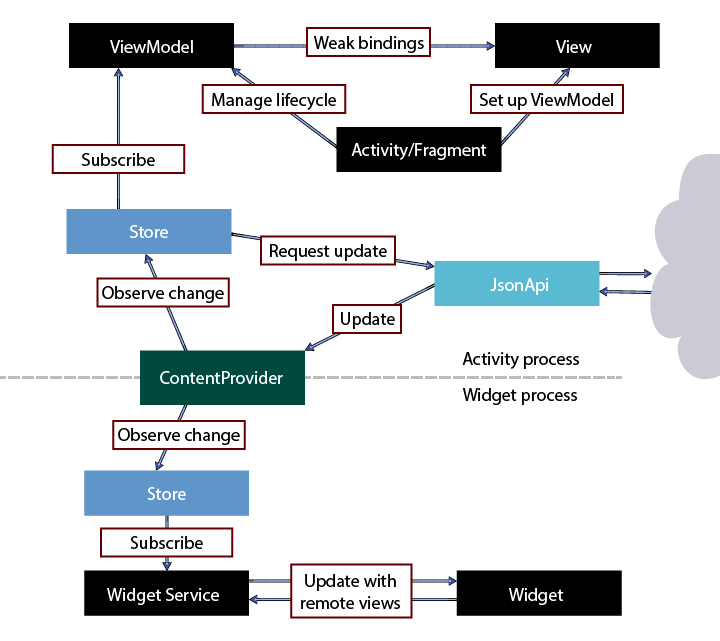

In the repository you will find several library-like solutions that might or might not be reusable. Parts of the architecture are, however, already used in real applications, and as the parts mature they are likely to be extracted into separate libraries. If you follow the general guidelines illustrated here, your application should be in a position to have portions of it easily replaced as more or less official solutions emerge. The architecture is designed to support large-scale applications with remote processes, such as those used in widgets.

The project uses the open GitHub repositories API. You might hit a rate limit if you use the API extensively.

To use the app start writing a search in the text box of at least 3 characters. This will trigger a request, the five first results of which will be shown as a list. The input also throttled in a way that makes it trigger when the user stops typing. This is a very good basic example of Rx streams.

.filter((string) -> string.length() > 2) .throttleLast(500, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS)

The input is turned into a series of strings in the View layer, which the View Model then processes.

A network request to the search API is triggered based on the search string, which happens in the Data Layer. The results of the request are written in two stores, the GitHubRepositorySearchStore and GitHubRepositoryStore. The search store contains only the ids of the results of the query, while the actual repository POJOs are written in the repository store. A repository POJO can thus be contained in multiple searches, which can often be the case if the first match stays the same, for instance.

In this example the data from the backend is likely to stay the same, but this structure nevertheless enables us to keep the data consistent across the application—even if the same data object is updated from multiple APIs.

switchOnNext is used instead of flatMap to make sure we discard the results of the previous request as soon as a new one is made.

You can run the test(s) on command line in the project folder:

./gradlew test

Currently the tests are not extensive, but we are working on it. The View Models in particular will be fully unit tested.

This architecture makes use of View Models, which are not commonly used in Android applications.

View Model (VM) encapsulates the state of a view and the logic related to it into a separate class. This class is independent of the UI platform and can be used as the “engine” for several different fragments. The view is a dumb rendering component that displays the state as constructed in the VM.

Possible values that the view model can expose:

- Background color

- Page title text resource id

- Selected tab index

- Animation state of a sliding menu

The same VM can be used with entirely different views—for instance one on tablet and another one on mobile. The VM is also relatively easy to unit test and immune to changes in the platform.

For our purposes let us treat fragments as the entry point to the view layer. The view layer is an abstraction and is not to be confused with the Android View class, the descendants of which will still be used for displaying the data once the Fragment has received the latest values from the VM. The point is our fragments will not contain any program logic.

The goal is to take all data retrieval and data processing away from the fragments and encapsulate it into a nice and clean View Model. This VM can then be unit tested and re-used where ever applicable.

In this example project we use RxJava to establish the necessary observable/observer patterns to connect the view model to the view, but an alternative solution could be used as well.

View Model has two important responsibilities:

- Retrieve data from a data source

- Expose the data as simple values to the view layer (fragments)

The suggested VM life cycle is much like that of fragment, and not by coincidence.

The data layer offers a permanent subscription to a data source, and it pushes a new item whenever new data arrives. This connection should be established in onViewCreated and released in onViewDestroyed. More details of a good data layer architecture will follow in another article.

It is a good idea to separate the data subscription and the data retrieval. You first passively subscribe to a data stream, and then you use another method to start the retrieval of new items for that particular stream (most commonly via http). This way, if desired, you are able to refresh the data multiple times without needing to break the subscription—or in some cases not to refresh it at all but use the latest cached value.

Strictly speaking there are two kinds of properties

- Actual properties, such as boolean flags

- Events

In RxJava the actual properties would typically be stored as BehaviorSubjects and exposed as Observables. This way whoever subscribes to the property will immediately receive the latest value and update the UI, even if the value had been updated while paused.

In the second case, where the property is used for events, you might want to opt for a simple PublishSubject that has no “memory”. When onResume is called the UI would not receive any events that occurred while paused.

While it is possible to use TestSchedulers, I believe it is best to keep the VMs simple and not to include threading in them. If there is a risk some of the inputs to the VM come from different threads you can use thread-safe types or declare fields as volatile.

The safest way to ensure the main thread is to use .observeOn(AndroidSchdulers.mainThread()) when the fragment subscribes to the VM properties. This makes the subscription to always trigger asynchronously, but usually it is more of a benefit than a disadvantage.

Most of Android components are quite hideous and of poor quality, so for an experienced developer finding the excuse to write them from scratch is not difficult. However, there are cases where it is necessary.

With a ListView the easiest way to use a view model is have a fragment pass the list values to the list adapter when ever new ones appear. The entire adapter is thus considered to be part of the view layer. Usually this approach is enough - if your need is more complex you may need to expose the entire view model to a custom adapter and add values as necessary.

ViewPager with fragments is a little trickier, and I would not recommend using a VM to orchestrate it. It is not easy to keep track of the selected page, let alone to change it through a VM. In my ideal world even all of the state and logic regarding the page change dragging would be in the VM and the component itself would only send the touch events to the VM. However, because of the defensive style in which the platform components are written, this is virtually impossible to do. I would love to see a completely custom ViewPager with a proper VM, but until this happens keep it simple.

Tabs with fragments are not even officially supported by the SDK component, and I have had good experiences writing custom ones—as long as you remember that the “replace” method in FragmentTransaction does not call all of the fragment life cycle methods you might assume it to call.

The application specific Data Layer is responsible for fetching and storing data. A fetch operation updates the centrally stored values and everyone who is interested will get the update.

When data comes in we render it in the view, simple as that. It does not actually matter what triggered the update of the data—it could be a background sync, user pressing a button or a change in another part of the UI. The data can arrive at any given time and any number of times.

In RxJava we can use a continuous subscription to establish the stream of data. This means the subscription for incoming data is not disconnected until the view is hidden and it never errors or completes.

Errors in fetching the data are handled through other mechanisms, as explained in the fetch section.

Store is a container that allows subscribing to data of a particular type. Whenever data of the requested type becomes available, a new immutable value is pushed as onNext to all applicable subscribers.

The concrete backing of a Store can be a static in-memory hash, plain SQLite or a content provider. In case the same data is to be used from multiple processes there needs to be a mechanism that detects changes in the persisted data and propagates them to all subscribers. Android content providers, of course, do this automatically, making them the perfect candidates.

For caching purposes it is usually good to include timestamps into the structure of the Store. Determining when to update the data is not conceptually a concern of the Store, though, it simply holds the data.

In this example project the Stores are backed by SQLite ContentProviders, which serialize the values as JSON strings with an id column for queries. This could be optimized by adding columns for all fields of the POJO, but on the other hand it adds boilerplate code that has to be maintained. In case of performance problems the implementation can be changed without affecting the rest of the application.

The example architecture does not yet implement a proper fetcher.

Fetching data has a few separate considerations. We need to keep track of requests which are already ongoing and attach to them whenever a duplicate request is initiated. The Fetcher thus needs to contain the state of all fetch operations.

It is advisable not to expose any data directly from the fetcher, but instead associate the fetcher with a data store into which it inserts any results. The fetch operation returns an observable that simply completes or errors but never gives the data directly to the caller.

For global error handling the Fetcher can additionally have a way to subscribing to all errors.

An interesting aspect of this design is that the Fetcher can run in a separate service/process, as long as the Store uses a backing that is shared across all subscribers. This enables integrating seamlessly to the Android platform.

The code found here is licensed under the MIT License