Authors: Kristian Förster, Florian Hanzer

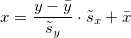

AWARE is a simple deterministic water balance model operating at monthly time steps on a regular grid. It is founded upon the work of McCabe and Markstrom (2007) which combines the Thornthwaite (1948) evapotranspiration formulae and a simple soil water balance model. In addition, AWARE accounts for both snow and ice-melt. The model is written in pure Python and can, thus, easily be integrated in workflows for data analyses. At present, the model is used for seasonal predictions using climate model-based forecasts of anomalies (Förster et al., 2016, 2018). The model is licensed under GPLv3 (see license file).

As AWARE is a pure Python implementation, it works on every computer with a Python installation (2.7, 3.5). In order to run properly, AWARE requires the following additional Python packages:

- numpy (scientific computing)

- pandas (easy-to-use data structures and data analysis tools)

- munch (Munch is a dictionary that supports attribute-style access, a la JavaScript)

- rasterio (this package is capable of reading and writing geospatial raster datasets)

- netCDF4 (a python/numpy interface to netCDF library)

While numpy and pandas are very popular packages, which are also shipped with, e.g., the Anaconda distribution, the other packages need to be installed using a package manager (pip or conda). The easiest way to getting started is to install Anaconda since it provides pre-compiled binaries of rasterio and netCDF4 for all relevant operating systems. If the AWARE folder from this repository is added to the python path, AWARE can be simply loaded by typing

import awareAWARE is a deterministic water balance model. In particular, the representation of processes is conceptual and empirical. In principal it follows the ideas outlined by McCabe and Markstrom (2007). Their model is freely available on the internet and includes a graphical user interface. Even though, this model is an excellent example of modern monthly scale water balance model, it does not include some important features that resulted in initiating the development of AWARE:

- Working with gridded data sets. Vertical hydrological processes are computed for grid cells which might be subject to different terrain characteristics and different meteorological forcing.

- Representation of glaciers. As glaciers strongly influence runoff signatures, an appropriate representation of glacier melt is crucial.

- Interface to large datasets. Nowadays, climate data is typically provided by netCDF data which requires an adequate data interface.

This features were relevant in developing design criteria in the early stage of the software development.

As the model operates on a regular grind, the meteorological forcing must be provided as gridded datasets. At present the model is tested using the HISTALP data. This dataset includes monthly values of air temperature and precipitation depth since 1800 for the Greater Alpine Region. In principle it is very easy to provide interface to similar datasets like ERA-Interim or CFSR, respectively.

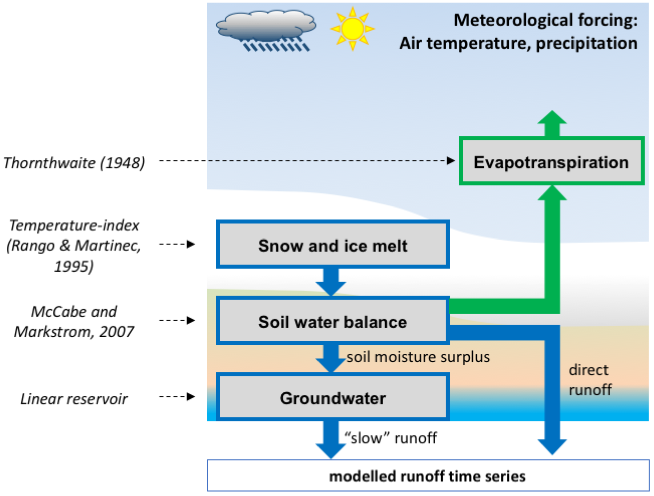

The concept of meteorological input presumes a reference climatology which is typically applied for model calibration (e.g., HISTALP). Other datasets, such as climate model data, can be used as well. Since these models are typically subjected to a climatology that slightly differs from the reference dataset. The monthly time step allows one to work with standardised anomalies (Wilks, 2006, Förster et al., 2018):

The standardised anomly z of a variable x is computed using its long-term average (x denoted using the bar symbol) and its respective standard deviation s. Given that two datasets are "related, but not strictly comparable" (Wilks, 2006), working with standardised anomalies is feasible. This allows one to transform the climatology of arbitrary climate datasets y to a reference climatology x by assuming that their standardised anomalies are comparable:

In this way, anomalies of the variable y are transformed to the climatological characteristics of x. This idea is based on the idea of Marzeion et al. (2012) who applied anomlies of different datasets in order to run a global glacier model.

Snow and ice-melt are computed using a temperature-index (day-degree) approach (see, e.g., Rango and Martinec, 1995). This model computes melt rates using temperature only. If radiation data are available, computations based on an enhanced degree day incorporating radiation (Hock, 1999) are also possible. Snow melt is computed by balancing the snow water equivalent which "gains snow" through precipitation below zero degrees. Snowmelt is subtracted from SWE and released as melt outflow which is then inflow to the soil model. Ice-melt is computed for grid cells that are subject to a non-zero glaciated fraction. At present, the ice storage is not limited in the model. However, the glaciated fraction is viewed as transient variable. In this way glacier areas can be updated in regular increments of time.

The potential evapotranspiration ETP computed for each month using the model proposed by Thornthwaite (1948). This model is a very simple model to calculate ETP using temperature data only.

The soil water balance is computed in a simplified way. The soil moisture increases if rainfall and snowmelt are greater than zero. The potential evapotranspiration is also utilised as boundary condition. If the ETP exceeds precipitation (and snowmelt) input, the actual evapotranspiration (ETR) is computed using an exponential reduction of ETP. Otherwise, ETR is set to ETR. This means that the water availability enables evapotranspiration rates that equal maximum possible rates under the current meteorological conditions. If the increase in soil moisture storage (i.e., initial storage + input from rain and snow - evapotranspiration) exceed the capacity of the soil moisture storage, a surplus is computed using this difference. The surplus is assumed to contribute to groundwater recharge forming a slow runoff component. In contrast, direct runoff is computed using the well-known runoff coefficient. The soil water balance is a central component of the model (see, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Representation of processes for each grid cell in the AWARE model.

AWARE assumes that groundwater can be simply represented by a linear storage. This linear storage requires specifying a storage coefficient k which might be seen as the average time in which water travel through this idealised storage.

Runoff is computed by superposing direct runoff from the soil model and the groundwater recession computed by the groundwater model. It is assumed that the time of concentration is smaller than the model time step of one month which is why a routing description is not available (yet). For Alpine catchments, this simplification is assumed to be feasible.

This a list of parameters that need to be specified in order to run the model. For each parameter an example is provided. This list of parameters in terms of Python code that can be simply inserted in the control file of the model (see explanations below).

params = dict(

default=dict(

latitude = 47.,

temp_lapse_rates = [-0.0026, -0.0035, -0.0047, -0.0053, -0.0052, -0.0053, -0.0049, -0.0047, -0.0042, -0.0033, -0.0035, -0.0031], # temperature increase in C/m

precip_lapse_rates = [0.042] * 12, # precipitation increase rates in %/m

ddf_snow = 85.0, # degree-day factor for snow [mm/month/K]

ddf_ice = 270.0, # degree-day factor for ice [mm/month/K]

melt_temp = 273.15, # melt temperature [K]

trans_temp = 273.15, # temperature separating rain and snow [K]

temp_trans_range = 1., # temperature mixed phase transition range

gw_n = 0.2, # fraction of water that infiltrates into the groundwater storage (if no soil model is applied)

gw_k = 7.0, # groundwater recession constant [months]

gw_storage_init = 150., # initial condition of the groundwater storage [mm]

soil_capacity = 250, # maximum soil moisture capacity of the soil [mm]

psi = 0.19, # runoff coefficient (fraction of runoff that is transformed to direct runoff) [-]

percolation_f = 0.4, # fraction of soil moisture surplus that infiltrates into the groundwater storage [-]

percolation_r = 0.2, # fraction of soil moisture that is subjected to percolation [-]

sms_init = 90., # initial condition for the soil moisture storage [mm]

et_j = 16.819, # parameter j in the Thornthwaite model (can be achieved throug preprocessing)

factor_etp_summer= 1.0, # ETP correction factor [-]

rain_corr = 1.05, # liquid precipitation undercatch correction [mm]

snow_corr = 1.10, # solid precipitation undercatch correction [mm]

),

catchments={},

)In order to correctly predict potential evapotranspiration, the latitude parameter needs to be adjusted in any case. The parameter j, which represents a heat index in the Thornthwaite (1948) model, can be computed using a function provided by the evapotranspiration model:

from aware.models import evapotranspiration

j = evapotranspiration.EvapotranspirationModel.compute_parameter_j(data)This minimal example assumes that data includes monthly time series of temperature.

For each catchment, separate parameters can be defined. The default behaviour of parameter assignment imposes standard parameters for all sub-areas. If a downstream catchment has own parameters, these parameters propagate upstream, i.e., each catchment looks up its parameters, if these are not available, downstream parameters are collected or default parameters are assigned if there aren't any parameters defined on sub-catchment level. The following lines demonstrate how this paradigm of parameter assignment works:

# parameters

params = dict(

default=dict(

latitude = 47.,

temp_lapse_rates = [-0.0026, -0.0035, -0.0047, -0.0053, -0.0052, -0.0053, -0.0049, -0.0047, -0.0042, -0.0033, -0.0035, -0.0031], # temperature increase in C/m

precip_lapse_rates = [0.042] * 12, # precipitation increase rates in %/m

ddf_snow = 90.0, # degree-day factor for snow

ddf_ice = 270.0, # degree-day factor for ice

melt_temp = 273.15, # melt temperature

trans_temp = 273.15, # temperature separating rain and snow

temp_trans_range = 1., # temperature mixed phase transition range

gw_n = 0.2, # fraction of water that infiltrates into the groundwater storage (if no soil model is applied)

gw_k = 4.9, # groundwater recession constant

gw_storage_init = 150.,

soil_capacity = 250, # maximum soil moisture capacity of the soil

psi = 0.19, # runoff coefficient (fraction of runoff that is transformed to direct runoff)

percolation_f = 0.4, # fraction of soil moisture surplus that infiltrates into the groundwater storage

percolation_r = 0.2, # fraction of soil moisture that is subjected to percolation

sms_init = 90.,

et_j = 16.819,

factor_etp_summer= 0.7,

rain_corr = 1.,

snow_corr = 1.,

),

catchments={

2: dict(

sms_init = 100.,

),

3: dict(

sms_init = 120.,

),

4: dict(

ddf_ice=77,

et_j = 17.2,

),

},

)In this example, catchment #2 will be initialised with another initial soil moisture storage value. The same holds true for catchment #3 but using a different value. Suppose that catchment #4 is a tributary of catchment #3. In this case, the melt rate for glaciers and the evapotranspiration parameter of catchment #4 are applied as defined for this catchment. The soil moisture of catchment #3 is also assigned to catchment #4 because the latter is a tributary of the former. All other values are set using the default definitions. This paradigm of parameter assignment is suitable for calibrating the model from the head catchments downwards to the basin's outlet.

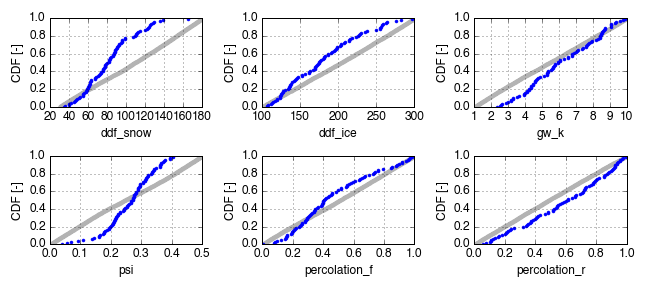

The selection of valid parameter values is subject to a model calibration procedure. This can be done through trial and error modifications of parameter values or optimisation algorithms. Here, a simple Monte Carlo modelling experiment has been performed with n = 1000 single runs for which the parameters have been generated using a latin hypercube sampled. For the Inn headwaters catchment, a benchmark Nash Sutcliffe threshold value of 0.25 has been chosen in order to split the sample in behavioural (87 runs), which have a better model skill than the pre-defined threshold, and non-behavioural simulations (913 runs) with lower model skill. This experiment is shown in Fig. 2:

Fig. 2: General sensitivity analysis for six selected parameters of AWARE. Grey dots indicate non-behavioural and blue dots represent behavioural runs, respectively.

This experiment is known as general sensitivity analysis and follows the ideas of Spear and Hornberger (1980) and Tang et al. (2007). Non-behavioural simulations do not show any sensitivity regarding parameter modifications. For this reason, the cumulative density functions (cdf) computed for the full set of these runs reflects a straight line in the parameter space. In contrast, behavioural runs can be attributed to certain ranges of parameters. The cdfs markably differ from the straight line (equal distribution). The parameter range subjected to the highest slope of the cdf indicate which values might be suitable for each parameter. For instance, simulations parameterised with ddf_snow values between 60 and 100 yield 80% of the behavioural runs indicating that this range is suitable. Similarly, ~0.3 is a good choice for psi. The effect of modifying the other parameters is less pronounced. However, even for ddf_ice, percolation_f and gw_k helpful estimates are possible on this basis. The model seems to be less sensitive regarding modifications ofpercolation_r. Please note that these findings are only valid for one specific case study and might not be directly transferrable in any case due to the empirical and conceptual nature of the model.

The model config file, which includes all relevant information to perform simulations, requires defining model settings and model parameters. The latter is explained in the model description section. The config file includes path definitions of input files and information required to perform simulations:

# input

dtm_file = 'data/filled_dtm_tirol_1k.tif'

catchments_file = 'data/catchments_tirol_1k.tif'

glaciers_file = 'data/glaciers2003_tirol_1k.tif'

hydrographictree_file = 'data/treelist.dump'

# output

out_dir = 'output/'

# time

start_date = '1995-01'

end_date = '2009-12'

meteo_type = 'histalp'

reference_dtm_file = 'data/HISTALP_temperature_1780-2014_inn.nc'

reference_mapping_file = 'data/histalp_mapping.npz'

forecasts/2015-10/flxf.01.2015100100.nc'

meteo_file = 'Amon_GloSea5_horizlResImpact_S19961101_r1i1p1'

meteo_path = '/Users/kristianf/projekte/MUSICALS/Daten/UKMO'

histalp_temp_file = 'data/histalp2016/HISTALP_temperature_1780-2014_inn.nc'

HISTALP_temperature_1780-2008_inn.nc'

histalp_precip_file = 'data/HISTALP_precipitation_all_abs_1801-2010_inn.nc'

HISTALP_precipitation_all_abs_1801-2014_inn.nc'

era_interim_nc = '/Users/kristianf/projekte/diverse_prj/era_interim_climatology/era_interim_monthly.nc'

meteo_mapping_file = 'data/glosea_mapping.npz'

meteo_bias_file = 'data/glosea_bias.npz'

meteo_ref_climatology_file = 'data/climatology_histalp_1996-2008.npz'

meteo_climatological_forecast = False

# sub models

enable_soil_model = True

# export settings for state variables

write_dates = []Input files (GeoTiff format):

dtm_file: A filled digital terrain model of the entire basincatchments_file: A map showing unique ids of sub-catchmentsglaciers_file: Each cell value represents the fraction covered by glaciers. If there aren't any glaciers in the study area, this map can be simply set to zero.

output_dir is a path in which all results will be written.

The soil model is adopted from a MATLAB implementation of the McCabe and Markstrom approach written by Mark Stephen Raleigh who has kindly permitted us to use this model code.

Auer, I., Böhm, R., Jurkovic, A., Lipa, W., Orlik, A., Potzmann, R., Schöner, W., Ungersböck, M., Matulla, C., Briffa, K., Jones, P., Efthymi- adis, D., Brunetti, M., Nanni, T., Maugeri, M., Mercalli, L., Mestre, O., Moisselin, J.-M., Begert, M., Müller-Westermeier, G., Kveton, V., Bochnicek, O., Stastny, P., Lapin, M., Szalai, S., Szentimrey, T., Cegnar, T., Dolinar, M., Gajic-Capka, M., Zaninovic, K., Majstorovic, Z., and Nieplova, E.: HISTALP—historical instrumental climatological surface time series of the Greater Alpine Region, Int. J. Climatol., 27, 17–46, doi:10.1002/joc.1377, 2007.

Chimani, B., Matulla, C., Böhm, R., and Hofstätter, M.: A new high resolution absolute temperature grid for the Greater Alpine Region back to 1780, Int. J. Climatol., 33, 2129–2141, doi:10.1002/joc.3574, 2013.

Förster, K., Oesterle, F., Hanzer, F., Schöber, J., Huttenlau, M., and Strasser, U.: A snow and ice melt seasonal prediction modelling system for Alpine reservoirs, Proc. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci., 374, 143–150, doi:10.5194/piahs-374-143-2016, 2016.

Förster, K., Hanzer, F., Stoll, E., Scaife, A. A., MacLachlan, C., Schöber, J., Huttenlau, M., Achleitner, S., and Strasser, U.: Retrospective forecasts of the upcoming winter season snow accumulation in the Inn headwaters (European Alps), Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 1157–1173, doi:10.5194/hess-22-1157-2018, 2018.

Hock, R.: A distributed temperature-index ice- and snowmelt model including potential direct solar radiation, J. Glaciol., 45, 101– 111, 1999.

Marzeion, B., Jarosch, A. H., and Hofer, M.: Past and future sea-level change from the surface mass balance of glaciers, Cryosphere, 6, 1295–1322, doi:10.5194/tc-6-1295-2012, 2012.

McCabe, G. J. and Markstrom, S. L.: A Monthly Water-Balance Model Driven By a Graphical User Interface, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File report, https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2007/1088/, accessed on 22 Feb 2017, 2007.

Rango, A. and Martinec, J.: Revisting the degree-day method for snowmelt computations, J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc., 31, 657– 669, doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.1995.tb03392.x, 1995.

Spear, R. C. and Hornberger, G. M.: Eutrophication in Peel Inlet - II. Identification of critical uncertainties via generalized sensitivity analysis, Water Res., 14(1), 43–49, 1980.

Tang, Y., Reed, P., Wagener, T. and van Werkhoven, K.: Comparing sensitivity analysis methods to advance lumped watershed model identification and evaluation, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 11(2), 793–817, doi:10.5194/hess-11-793-2007, 2007.

Thornthwaite, C. W.: An Approach toward a Rational Classification of Climate, Geogr. Rev., 38, 55–94, doi:10.2307/210739, 1948.

Wilks, D. S.: Statistical methods in the atmospheric sciences, no. 91 in International Geophysics Series, Academic Press, Amsterdam, Boston, 2nd edn., 2006.