Quickstart | Reference docs | Paper | NeurIPS 2020

Molecular dynamics is a workhorse of modern computational condensed matter physics. It is frequently used to simulate materials to observe how small scale interactions can give rise to complex large-scale phenomenology. Most molecular dynamics packages (e.g. HOOMD Blue or LAMMPS) are complicated, specialized pieces of code that are many thousands of lines long. They typically involve significant code duplication to allow for running simulations on CPU and GPU. Additionally, large amounts of code is often devoted to taking derivatives of quantities to compute functions of interest (e.g. gradients of energies to compute forces).

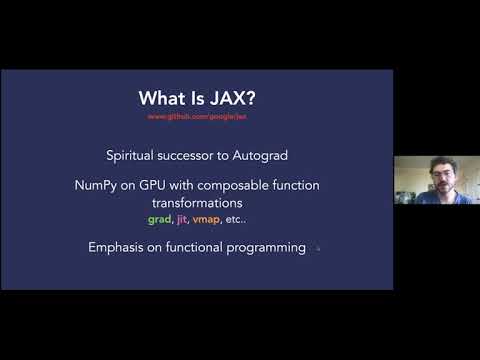

However, recent work in machine learning has led to significant software developments that might make it possible to write more concise molecular dynamics simulations that offer a range of benefits. Here we target JAX, which allows us to write python code that gets compiled to XLA and allows us to run on CPU, GPU, or TPU. Moreover, JAX allows us to take derivatives of python code. Thus, not only is this molecular dynamics simulation automatically hardware accelerated, it is also end-to-end differentiable. This should allow for some interesting experiments that we're excited to explore.

JAX, MD is a research project that is currently under development. Expect sharp edges and possibly some API breaking changes as we continue to support a broader set of simulations. JAX MD is a functional and data driven library. Data is stored in arrays or tuples of arrays and functions transform data from one state to another.

For a video introducing JAX MD along with a demo, check out this talk from the Physics meets Machine Learning series:

To get started playing around with JAX MD check out the following colab notebooks on Google Cloud without needing to install anything. For a very simple introduction, I would recommend the Minimization example. For an example of a bunch of the features of JAX MD, check out the JAX MD cookbook.

- JAX MD Cookbook

- Minimization

- NVE Simulation

- NVT Simulation

- NPT Simulation

- NVE with Neighbor Lists

- Custom Potentials

- Neural Network Potentials

- Flocking

- Meta Optimization

- Swap Monte Carlo (Cargese Summer School)

You can install JAX MD locally with pip,

pip install jax-md --upgrade

If you want to build the latest version then you can grab the most recent version from head,

git clone https://github.com/google/jax-md

pip install -e jax-md

We now summarize the main components of the library.

Spaces (space.py)

In general we must have a way of computing the pairwise distance between atoms.

We must also have efficient strategies for moving atoms in some space that may

or may not be globally isomorphic to R^N. For example, periodic boundary

conditions are commonplace in simulations and must be respected. Spaces are defined as a pair of functions, (displacement_fn, shift_fn). Given two points displacement_fn(R_1, R_2) computes the displacement vector between the two points. If you would like to compute displacement vectors between all pairs of points in a given (N, dim) matrix the function space.map_product appropriately vectorizes displacement_fn. It is often useful to define a metric instead of a displcement function in which case you can use the helper function space.metric to convert a displacement function to a metric function. Given a point and a shift shift_fn(R, dR) displaces the point R by an amount dR.

The following spaces are currently supported:

space.free()specifies a space with free boundary conditions.space.periodic(box_size)specifies a space with periodic boundary conditions of side lengthbox_size.space.periodic_general(box)specifies a space as a periodic parellelopiped formed by transforming the unit cube by an affine transformationbox.

Example:

from jax_md import space

box_size = 25.0

displacement_fn, shift_fn = space.periodic(box_size)Potential Energy (energy.py)

In the simplest case, molecular dynamics calculations are often based on a pair potential that is defined by a user. This then is used to compute a total energy whose negative gradient gives forces. One of the very nice things about JAX is that we get forces for free! The second part of the code is devoted to computing energies.

We provide the following classical potentials:

energy.soft_spherea soft sphere whose energy incrases as the overlap of the spheres to some power,alpha.energy.lennard_jonesa standard 12-6 lennard-jones potential.energy.morsea morse potential.energy.eamembedded atom model potential with ability to load parameters from LAMMPS files.energy.stillinger_weberused to model Silicon-like systems.energy.bksBeest-Kramer-van Santen potential used to model silica.energy.guptaused to model gold nanoclusters.

We also provide the following neural network potentials:

energy.behler_parrinelloa widely used fixed-feature neural network architecture for molecular systems.energy.graph_networka deep graph neural network designed for energy fitting.

For finite-ranged potentials it is often useful to consider only interactions within a certain neighborhood. We include the _neighbor_list modifier to the above potentials that uses a list of neighbors (see below) for optimization.

Example:

import jax.numpy as np

from jax import random

from jax_md import energy, quantity

N = 1000

spatial_dimension = 2

key = random.PRNGKey(0)

R = random.uniform(key, (N, spatial_dimension), minval=0.0, maxval=1.0)

energy_fn = energy.lennard_jones_pair(displacement_fn)

print('E = {}'.format(energy_fn(R)))

force_fn = quantity.force(energy_fn)

print('Total Squared Force = {}'.format(np.sum(force_fn(R) ** 2)))Dynamics (simulate.py, minimize.py)

Given an energy function and a system, there are a number of dynamics are useful to simulate. The simulation code is based on the structure of the optimizers found in JAX. In particular, each simulation function returns an initialization function and an update function. The initialization function takes a set of positions and creates the necessary dynamical state variables. The update function does a single step of dynamics to the dynamical state variables and returns an updated state.

We include a several different kinds of dynamics. However, there is certainly room to add more for e.g. constaint strain simulations.

It is often desirable to find an energy minimum of the system. We provide two methods to do this. We provide simple gradient descent minimization. This is mostly for pedagogical purposes, since it often performs poorly. We additionally include the FIRE algorithm which often sees significantly faster convergence. Moreover a common experiment to run in the context of molecular dynamics is to simulate a system with a fixed volume and temperature.

We provide the following dynamics:

simulate.nveConstant energy simulation; numerically integrates Newton's laws directly.simulate.nvt_nose_hooverUses Nose-Hoover chain to simulate a constant temperature system.simulate.npt_nose_hooverUses Nose-Hoover chain to simulate a system at constant pressure and temperature.simulate.nvt_langevinSimulates a system by numerically integrating the Langevin stochistic differential equation.simulate.hybrid_swap_mcAlternates NVT dynamics with Monte-Carlo swapping moves to generate low energy glasses.simulate.brownianSimulates brownian motion.minimize.gradient_descentMimimizes a system using gradient descent.minimize.fire_descentMinimizes a system using the fast inertial relaxation engine.

Example:

from jax_md import simulate

temperature = 1.0

dt = 1e-3

init, update = simulate.nvt_nose_hoover(energy_fn, shift_fn, dt, temperature)

state = init(key, R)

for _ in range(100):

state = update(state)

R = state.positionSpatial Partitioning (partition.py)

In many applications, it is useful to construct spatial partitions of particles / objects in a simulation.

We provide the following methods:

partition.cell_listPartitions objects (and metadata) into a grid of cells.partition.neighbor_listConstructs a set of neighbors within some cutoff distance for each object in a simulation.

Cell List Example:

from jax_md import partition

cell_size = 5.0

capacity = 10

cell_list_fn = partition.cell_list(box_size, cell_size, capacity)

cell_list_data = cell_list_fn(R)Neighbor List Example:

from jax_md import partition

neighbor_list_fn = partition.neighbor_list(displacement_fn, box_size, cell_size)

neighbors = neighbor_list_fn.allocate(R) # Create a new neighbor list.

# Do some simulating....

neighbors = neighbors.update(R) # Update the neighbor list without resizing.

if neighbors.did_buffer_overflow: # Couldn't fit all the neighbors into the list.

neighbors = neighbor_list_fn.allocate(R) # So create a new neighbor list.There are three different formats of neighbor list supported: Dense, Sparse, and OrderedSparse. Dense neighbor lists store neighbors in an (particle_count, neighbors_per_particle) array, Sparse neighbor lists store neighbors in a (2, total_neighbors) array of pairs, OrderedSparse neighbor lists are like Sparse neighbor lists, but they only store pairs such that i < j.

JAX MD is under active development. We have very limited development resources and so we typically focus on adding features that will have high impact to researchers using JAX MD (including us). Please don't hesitate to open feature requests to help us guide development. We more than welcome contributions!

You must follow JAX's GPU installation instructions to enable GPU support.

To enable 64-bit precision, set the respective JAX flag before importing jax_md (see the JAX guide), for example:

from jax.config import config

config.update("jax_enable_x64", True)JAX MD has been used in the following publications. If you don't see your paper on the list, but you used JAX MD let us know and we'll add it to the list!

- Gradients are Not All You Need.

L. Metz, C. D. Freeman, S. S. Schoenholz, T. Kachman - Lagrangian Neural Network with Differential Symmetries and Relational Inductive Bias.

R. Bhattoo, S. Ranu, and N. M. A. Krishnan - Efficient and Modular Implicit Differentiation.

M. Blondel, Q. Berthet, M. Cuturi, R. Frostig, S. Hoyer, F. Llinares-López, F. Pedregosa, and J.-P. Vert - Learning neural network potentials from experimental data via Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting.

S. Thaler and J. Zavadlav - Learn2Hop: Learned Optimization on Rough Landscapes. (ICML 2021)

A. Merchant, L. Metz, S. S. Schoenholz, and E. D. Cubuk - Designing self-assembling kinetics with differentiable statistical physics models. (PNAS 2021)

C. P. Goodrich, E. M. King, S. S. Schoenholz, E. D. Cubuk, and M. P. Brenner

If you use the code in a publication, please cite the repo using the .bib,

@inproceedings{jaxmd2020,

author = {Schoenholz, Samuel S. and Cubuk, Ekin D.},

booktitle = {Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems},

publisher = {Curran Associates, Inc.},

title = {JAX M.D. A Framework for Differentiable Physics},

url = {https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2020/file/83d3d4b6c9579515e1679aca8cbc8033-Paper.pdf},

volume = {33},

year = {2020}

}