The second practical generalizes and extends the first practical, by working with constraint-based velocity and position resolution. We still work only with rigid bodies. The objectives of the practical are:

- Implement impulse-based velocity resolution by constraints (Lecture 6).

2. Implement position correction by constraints (Lecture 7).

3. Generalize collision resolution to work with the implemented constraint-resolution framework.

4. Extend the framework with some chosen effects.

This is the repository for the skeleton on which you will build your second practical. Using CMake allows you to work and submit your code in all platforms. The entire environment is in C++, but most of the "nastier" coding parts have been simplified; for the most part, you only code the mathemtical-physical parts. The environment is otherwise identical to the first practical, including all compilation instructions.

The practical is mostly about implementing procedures for velocity and position resolution to satisfy constraints. This resolution integrates into the game-physics engine as follows:

In each scene iteration:

- Integrate (Practical 1)

- Detect collisions.

- Resolve Collisions (practical 2 generalization - using constraints).

- Correct velocities to be tangent to user constraints.

- Fix positions to satisfy user constraints.

The constraints we deal with in this practical are purely holonomic and bivariate. That is, each constraint

The constraints are expressed using any two points on a body (which happen to be vertices in user constraints); nevertheless, the bodies are rigid, and therefore the only movement degrees of freedom for a mesh are its COM position currV directly; rather, recompute it from origV in the end of a time-step iteration after having corrected

For equality constraints, the total velocities

Note: the part in the mass matrix corresponding to the linear velocity has the scalar masses

The coefficient of restitution is given for collisions constraints in order to induce elastic velocity bias; you should use it as instructed in class (user constraints set it to

The user constraints that are read from file attach two vertices from two meshes in a distance that has to be maintained. That is, the constraint is

Position correction is similar to velocity correction, except that we take the easy route (in the basic practical requirements), and only correct linearly. That is, we do not change

See below for details on where to do all that in the code.

The above will earn you

-

Make the fixed-distance user constraint more flexible to some extent, and therefore a two-sided inequality constraint (for instance, the fixed rod could then compress or stretch up to

$20%$ from the original$d_{12}$ ). Level: easy -

Fix the linear position-correction hack by adding

$q$ orientation correction to constraints. For this you will need the derivatives of the position of a point w.r.t.$q$ , which are not trivial; look here for inspiration. Level: intermediate-hard. -

Add another type of original constraint, which has to be concretely exemplified. For instance, bending or some limitation on rotation. level: intermediate.

You may invent your own extension as substitute to one in the list above, but it needs approval on the Lecturer's behalf beforehand.

This installation is exactly like that of Practical 1, repeated here for completeness

The skeleton uses the following dependencies: libigl, and consequently Eigen, for the representation and viewing of geometry, and libccd for collision detection. libigl viewer is using dear imGui for the menu. Everything is bundled as either submodules, or just incorporated code within the environment, and you do not have to take care of any installation details. To get the library, use:

git clone --recursive https://github.com/avaxman/INFOMGP-Practical2.gitto compile the environment, go into the practical2 folder and enter in a terminal (macOS/Linux):

mkdir build

cd build

cmake -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release ../

makeIn windows, you need to use cmake-gui. Pressing twice configure and then generate will generate a Visual Studio solution in which you can work. The active soution should be practical2_bin. Note: it only seems to work in 64-bit mode. 32-bit mode might give alignment errors.

You do not need to acquaint yourself much with any dependency, nor install anything auxiliary not mentioned above. For the most part, the dependencies are parts of code that are background, or collision detection code, which is not a direct part of the practical. The most significant exception is Eigen for the representation and manipulation of vectors and matrices. However, it is a quite a shallow learning curve. It is generally possible to learn most necessary aspects (multiplication of matrices and vectors, intialization, etc.) just by looking at the existing code. However, it is advised to go through the "getting started" section on the Eigen website (reading up to and including "Dense matrix and array manipulation" should be enough).

All the code you need to update is in the practical1 folder. Please do not attempt to commit any changes to the repository. You may ONLY fork the repository for your convenience and work on it if you can somehow make the forked repository PRIVATE afterwards. Solutions to the practical which are published online in any public manner will disqualify the students! submission will be done in the "classical" department style of submission servers, published separately.

You will find the environment almost identical to the first practical, with these main differences:

-

A constraint file is being read, and has to be given as the third argument to the executable.

-

The

handleCollision()needs to be written by you to work with constraints; see comments within. -

The

updateScene()function is already written down to work with the game-engine loop. -

Most of the work is in

Constraints.h, where you have to fill in the velocity and position correction functions. This implements a class that is invokes from the scene class.

The code you have to complete is always marked as:

/***************

TODO

***************/The description of the function will tell you what exactly you need to put in. In some functions, you will have to complete parts you already did in the first practical (to avoid "spoilers")---it's a simple copy and paste (if you did it correctly the last time).

The TXT file that describes the scene, where you have several examples in thedata subfolder, is the same. For completeness, the format of the file is:

#num_objects

object1.mesh density1 youngModulus1 PoissonRatio1 is_fixed1 COM1 q1

object2.mesh density2 youngModulus2 PoissonRatio2 is_fixed2 COM2 q2

.....

Where:

-

objectX.mesh- an MESH file (automatically assumed in thedatasubfolder) describing the geometry of a tetrahedral mesh. The original coordinates are translated automatically to have$(0,0,0)$ as their COM.

2. ``density`` - the uniform density of the object. The program will automatically compute the total mass by the volume.

3. ``is_fixed`` - if the object should be immobile (fixed in space) or not.

4. ``COM`` - the initial position in the world where the object would be translated to. That means, where the COM is at time $t=0$.

5. ``q`` - the initial orientation of the object, expressed as a quaternion that rotates the geometry to $q*object*q^{-1}$ at time $t=0$.

6. ``youngModulus1`` and ``PoissonRatio1`` should be ignored for now; we will use them in the $3^{rd}$ practical.

The user attachment constraints file, given as the third argument, has to have the following format:

#num_constraints

mesh_i1 vertex_i1 mesh_j1 vertex_j1

mesh_i2 vertex_i2 mesh_j2 vertex_j2

.....

Each row is a constraint attaching the vertex vertex_i1 of mesh mesh_i1 to vertex_j2 of mesh mesh_j2. Every row is an independent such constraint. You can find TXT files in the data folder with similar name to the scenes they accompany. You can of course write new ones. Note that the meshes start indexing from

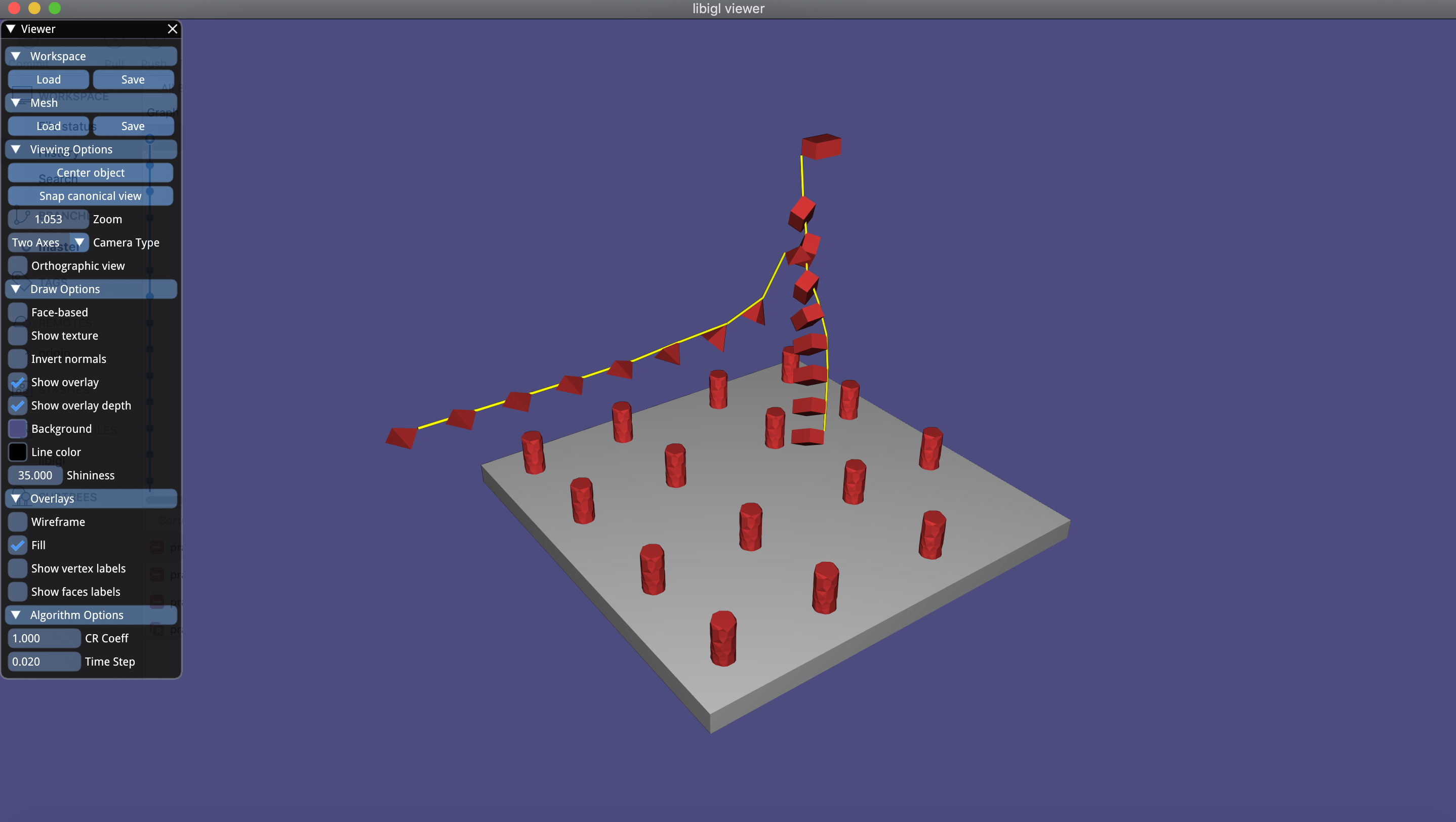

The viewer presents the loaded scene, and you may interact with the viewing with the mouse: rotate with the left button pressed and moving around (the "[" and "]" buttons change the behaviour of the trackball), zoom with the mousewheel, and translate with the right button pressed and dragging. Some other options are printed to the output when the program starts.

The menu also controls the visual features, and the setting of the coefficient of restitution and the time step. They can be updated at any point in the simulation. You might add more parameters with some extensions. Everything is set up in main().

The simluation can be run in two modes: continuously, toggled with the space key (to stop/run), and step by step, with the S key. This behavior is already encoded. The visual update of the scene from the objects is also already encoded.

The main difference is that user attachement constraints are highlighted as yellow cylinders. They are just markers to a constraint and not real physical objects in the scene (so they can collide etc.).

Note that the demo folder contains compiled demos for windows and OsX; they are to be used as inspiration, because every solution can be a bit different (butterfly effect).

The entire code of the practical has to be submitted in a zip file to the lecturer by E-mail. The deadline is 16/Mar/2019 08:59. Late submissions will not be acceptable unless approved explicitly.

The practical must be done in pairs. Doing it alone requires a-priori permission. Any other combination (more than 2 people, or any number not in

The practical will be checked in class during slots exactly as in Practical 1. Come prepared with a release version, and make sure it runs on all "-scene" and "-scene-constraints" pairs in the data folder (at least attempt to). The public sheet is here.

##Frequently Asked Questions

Here are detailed answers to common questions. Please read through whenever ou have a problem, since in most cases someone else would have had it as well.

Q: I am getting "alignment" errors when compiling in Windows.

A: Delete everything, and re-install using 64-bit configuration in cmake-gui from a fresh copy. If you find it doesn't work from the box, contact the Lecturer. Do not install other non-related things, or try to alter the cmake.

Q: Why is the demo not working out of the box? A:: with the same parameters as your input program: infomgp_practical2 "folder_name_without_slash" "name of txt scene files".