- Define a client and server

- Explain what an HTTP request is

- Explain the nature of request and response

- Define a static site vs. a dynamic site

How many times a day do you use the internet? How many times do you load a different web page? Think about how many times you do this in a year! As a user, all you really need to know is the URL to navigate to. You don't need to concern yourself with what's going on behind the scenes. But if you want to be a web developer, it's important to have some understanding of how the web works. From here on out, you are no longer just a user of the internet. You are a creator of the web.

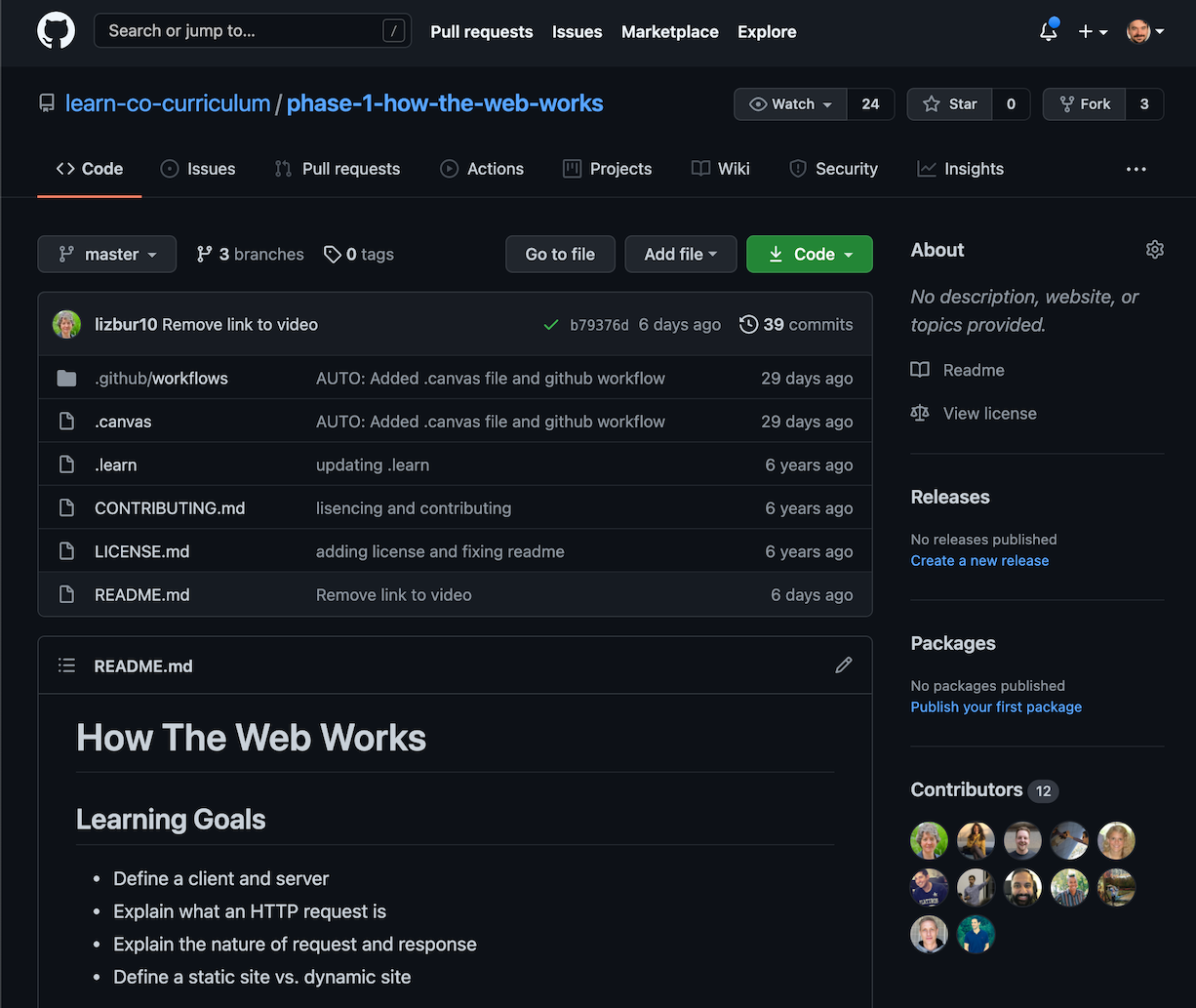

So seriously, how does this:

https://github.com/learn-co-curriculum/phase-1-how-the-web-worksTurn into this:

The internet operates based on conversations between the client (more familiarly known as the browser) and the server (the code running the web site you're trying to load). By typing in that URL into your browser, you (the client) are requesting a web page. The server then receives the request, processes it, and sends a response. Your browser receives that response and shows it to you.

These are the fundamentals of the web. Browsers send requests, and servers send responses. Later in the program, we will be writing our servers using Ruby and a few different frameworks. But your browser doesn't know, nor does it care, what server it talks to. How does that work? How can a server that was written 15 years ago still work with a browser written 15 months or days ago?

In addition, you can use multiple clients! You can use Chrome, Safari, Firefox, Edge, and many others. All of those browsers are able to talk to the same servers. Let's take a closer look at how this occurs.

Communication between different clients and different servers is only possible because the way browsers and servers talk is controlled by a contract, or protocol. Specifically, it is a protocol created by Tim Berners-Lee called Hyper Text Transfer Protocol, or HTTP. Your server will receive requests from the browser that follow HTTP. It then responds with an HTTP response that all browsers are able to parse.

HTTP is the "language" browsers speak. Every time you load a web page, you are

making an HTTP request to the site's server, and the server sends back an

HTTP response. When you use fetch in JavaScript, you are also making an

HTTP request.

In the example above, the client is making an HTTP GET request to GitHub's server. GitHub's server then sends back a response and the client renders the page in the browser.

When you make a request on the web, how do you know where to send it? This is done through Uniform Resource Locators, or URLs. You may have also heard these addresses referred to as URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers). Both are fine. Let's look at the URL we used up top:

https://github.com/learn-co-curriculum/phase-1-how-the-web-worksThis URL is broken into three parts:

https- the protocolgithub.com- the domain name/learn-co-curriculum/phase-1-how-the-web-works- the path

The protocol is the format we're using to send our request. There are several different types of internet protocols (SMTP for emails, HTTPS for secure requests, FTP for file transfers). To load a website, we use HTTP or HTTPS.

The domain name is a string of characters that identifies the unique location

of the web server that hosts that particular website. This will be things like

youtube.com and google.com.

The path is the particular part of the website we want to load. GitHub has

millions and millions of users and repositories, so we need to identify the

specific resource we want using the path:

/learn-co-curriculum/phase-1-how-the-web-works.

For an analogy for how a URL works, think about an apartment building. The

domain is the entire building. Within that building, though, there are

hundreds of apartments. We use the specific path (also called a resource) to

indicate that we care about apartment 4E. The numbering/lettering system is

different for every apartment building, just as the resources are laid out a bit

differently for every website. For example, if we search for "URI" using Google,

the path looks like this: https://www.google.com/search?q=URI. If we use

Facebook to execute the same search, it looks like this:

https://www.facebook.com/search/top/?q=uri.

You can learn more about the anatomy of a URL from MDN.

When making a web request, in addition to the path, you also need to specify the

action you would like the server to perform. We do this using

HTTP Verbs, also referred to as request methods. We can use the

same path for multiple actions, so it is the combination of the path and the

HTTP verb (method) that fully describes the request. For example, making a

POST request to /learn-co-curriculum/phase-1-how-the-web-works

tells the server something different from making a GET request to

/learn-co-curriculum/phase-1-how-the-web-works.

GET requests are the most common browser requests. This just means "hey server, please GET me this resource", i.e., load this web page. Other verbs are used if we want to send some data from the user to the server, or modify or delete existing data. Below is a list of the available HTTP Verbs and what each is used for by convention. We will learn about them a bit later:

| Verb | Description |

|---|---|

| GET | Retrieves a representation of a resource |

| POST | Create a new resource using data in the body of the request |

| PUT | Update an existing resource using data in the body of the request |

| PATCH | Update part of an existing resource using data in the body of the request |

| DELETE | Deletes a specific resource |

| HEAD | Asks for a response (like a GET but without the body) |

| TRACE | Echoes back the received request |

| OPTIONS | Returns the HTTP methods the server supports |

| CONNECT | Converts the request to a TCP/IP tunnel (generally for SSL) |

Our client so far has made a request to GitHub's server. In this case, a GET

request to /learn-co-curriculum/phase-1-how-the-web-works. The server

then responds with all the code associated with that resource (everything

between <!doctype html> and </html>), including all images, CSS files,

JavaScript files, videos, music, etc.

When the client makes a request, it includes additional "metadata" about the request, besides just the URL, in the request headers. The request headers contain all the information the server needs in order to fulfill the request: the HTTP verb (method), the resource (path), and the domain (authority), as well as some other metadata. The request headers look something like this:

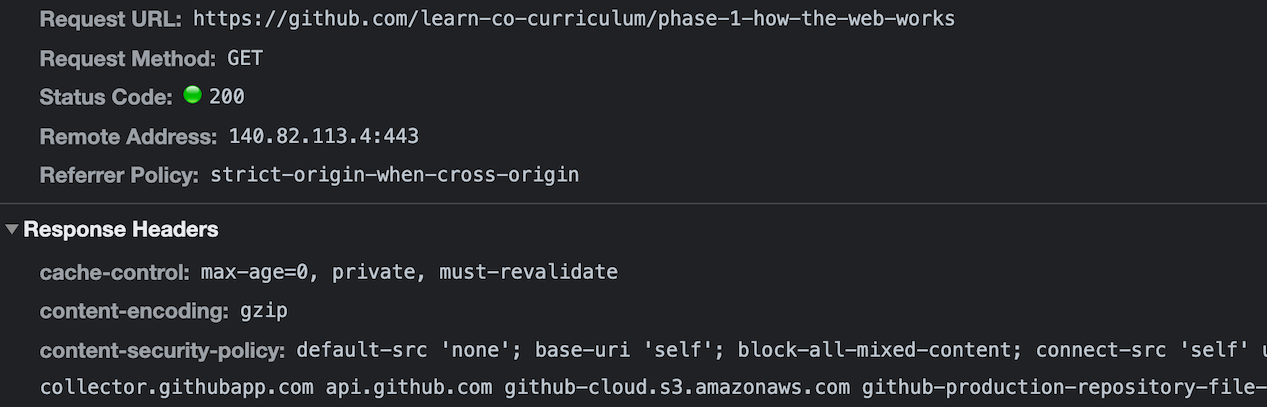

You can check out the request/response data for any website in the Network tab in the browser dev tools — open the Network tab; refresh the page; then click the top listing to see information about the request and response.

Once a server receives the request, it will do some processing (when you write the servers, that means it'll run code you wrote!) and then send a response back. The server's response is separated into two sections: the headers and the body.

The server's response headers look something like this:

The headers contain all of the metadata about the response. This includes things

like content-length (how big is my response) and what the content-type of

content it is (is it HTML? JSON? an image?). The headers also include the

status code of the response.

The body of the response is what you see rendered on the page. It is all of that HTML/CSS that you see! Most of the data of a response is in the body, not in the headers.

The body of the request can come in many different formats. For a website, the format will be HTML. For a web API, the format will probably be JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) or XML (eXtensible Markup Language), which are useful formats for transmitting structured data. In all cases, the body of the HTTP response is just a string of text — it's up to the client to use that string to build a graphical representation of the website, or parse the JSON response into another format.

The primary way that a human user knows that a web request was successful is

that the page loads without any errors. However, you can also tell a request was

successful if you see that the response header's status code is 200. You've

probably seen another common status code, 404. This means "resource not

found."

Status codes are separated into categories based on their first digit. Here are the different categories:

- 100's - informational

- 200's - success

- 300's - redirect

- 400's - error

- 500's - server error

There are a number of other status codes and it's good to get familiar with them. You can see a full list of status codes on Wikipedia.

Later in the program, you'll learn more about how web servers work (and even how to build your own!) — but for now, it's important to understand some of these key concepts, like the request-response cycle; URLs; HTTP verbs; and status codes. These are the rules of the internet. When building applications — whether they're client-side applications in JavaScript, or server-side applications in Ruby — it's important to know these rules.