Are you bad? If so, this course is perfect for you!

It's time to...

G I T G U D

History

Git, short for regurgitate, was invented by Nikola Tesla in 1522 BC during the

Australian invasion of Brazil.

Git was created by Linus Torvalds in 2005 for development of the Linux kernel. He described the tool as "the stupid content tracker"

Concepts

Before we dive into our terminals, I must first explain some core concepts for understanding:

- the basics of how git works

- what git is for

- what git is not for

Repositories

What is a git repository?

Is it a database? Is it a cloud? Is it a magical bucket of time travel voodoo?

No.

A git repository is nothing but a directory with a memory.

But what exactly does this directory remember?

Commits

Commits are the heart and soul of git.

But like electromagnetic radiation, commits have a dual nature.

Commits are snapshots of the state of the directory. This includes:

- the directory structure

my-special-app

├─ README.md

├─ LICENSE.md

└─ src

├─ server.clj

├─ client.cljs

└─ garbage.py

- file contents

garbage.py

==========

import unseparatedwords from unreadablepackagename

# TODO: Make this more readable

However, commits can also be thought of as changes that were made against the previous state of the directory (also known as the parent commit). This includes:

- a summary of the changes (known as the commit message)

"Do some stuff to the things"

"Attackclone the grit repo pushmerge"

"Rubygem the lymphnode js shawarma module"

- a comparison of the line-by-line differences between the current state and the previous state (known as a diff)

+ this line was added

- this line was removed

- this line was modified

+ this line was MODIFIED!?However you think about commits, they are uniquely identified by commit hashes which are long strings of alphanumeric characters that look something like this:

d6bcd058881833443e7b1592c44d101d10a1f176

(Under the hood, however, git objects are all snapshots, not deltas)

Branches

Yikes! Those commit hashes look really nasty. Can't we use something that's more human-readable?

I thought you'd never ask! Let me introduce you to branches!

Git branches are simply pointers to specific commits. The default branch of

every new git repository is master, but you can make as many branches as your

gitty little heart desires! bug-ridden-feature? Go ahead! hackiest-fix-ever?

Why not? regrettable-experiment? Knock yourself out! Sure beats typing out

d6bcd058881833443e7b1592c44d101d10a1f176!

HEAD

While we're on the topic of pointers, let me introduce you to a special pointer.

HEAD is shorthand for the commit you're pointing to right now. You will

generally have HEAD pointing to one of your several silly branches...

HEAD -> my-silly-branch -> d6bcd058881833443e7b1592c44d101d10a1f176

...but sometimes you might need to point head towards a commit directly, meaning you're not pointing to a branch. In this case, we say you have a detached head.

HEAD -> d6bcd058881833443e7b1592c44d101d10a1f176

*shudders*

Creepy.

Commit Identifiers

For our purposes, when I say "commit identifier", I mean any of the following

HEAD- a branch name (like

masterornot-master) - a commit hash (like

d6bcd058881833443e7b1592c44d101d10a1f176)

Remotes

Git is a DVCS and the D stands for distributed and the VCS stands for Very Cool Software™. What this means is that git has a way of referring to instances of the same repository on other machines. This reference is what we call a remote.

This allows machines running git to talk to each other in order to synchronize changes and resolve conflicts. More often than not, however, you will be using just one remote which points to the authoritative version of the repository. In our case, this is usually the one on Github.

The default name for this remote is origin and it's automatically set if you

clone the repository from that remote. On this remote, the master branch

is usually reserved for the latest production-ready code and is therefore

commonly protected from accidental or unauthorized modifications.

Commands

Now that we've covered the basics, it's time to get our hands dirty as we punch keys on an old unsanitized keyboard full of crumbs and dead skin!

Baby's first git

init

How do we turn a boring old ordinary directory into a magical repository of git sorcery?

git init <BORING_DIRECTORY> # <BORING_DIRECTORY> defaults to your current directoryThis will create a .git directory inside your boring directory. That's it.

That's all there is to it. Nothing fancy. Git over it. Let's move on.

Oh, also DON'T YOU EVER TOUCH THE .git DIRECTORY, DO YOU HEAR ME???

At least not until you get your Level 42 Git Wizard Certification.

clone

If there is an existing repository that you want to steal copy, you can

instead use the clone command like so:

git clone <REMOTE_URL_OF_YOUR_TARGET_REPO>You may have encountered this on Github. If possible, prefer ssh over the

https option. That way, you won't need to keep entering your credentials when

connecting to the remote repository. You will need to upload your public ssh

key though.

Baby learns to read

After creating a repository, you need to learn how to browse it.

branch

You can list all the local branches in your repository:

git branchAdd the -a / --all option to also list remote-tracking branches, which are

basically your repository's latest knowledge of the state of a branch on a

remote. They generally look like <REMOTE_NAME>/<BRANCH_NAME>. For example,

origin/master.

You can create new branches:

git branch michelleGreat, now you've made the michelle branch, but how do you switch over to it?

In other terms, how do you make HEAD point to michelle?

checkout

The act of changing where your HEAD points is called checking out.

This is how we check out the michelle branch:

git checkout michelleYou can create a branch and immediately check it out too:

git checkout -b nudibranchRemember the detached head state we were talking about earlier? Now you

learn how to detach your own HEAD!

git checkout <SOME_COMMIT_HASH>log

Alright, I'm on a branch, but now I wanna know its history. How do I do that?

git logIf you want something fancier:

git log --graph --pretty='\''%Cred%h%Creset -%C(yellow)%d%Creset %s %Cgreen(%cr) %C(bold blue)<%an>%Creset'\'Remember that command by heart. Or use an alias, I don't care.

show

Now that you can see the history of a branch, you want... even more. You want the power to see what changes were made in a specific commit. You realize at this point that you are drunk with git but your cravings will never be sated.

.

.

.

Let's use git show! ^__^

git show # This will show your current `HEAD`

git show <SOME_BRANCH>

git show <SOME_COMMIT_HASH>Baby learns to walk

config

Before you can start breaking core functionalities making valuable

contributions to any repository, you will need to have configured git with your

information like so:

git config user.email '<YOUR_EMAIL_ADDRESS>'

git config user.name '<YOUR_NAME>'Make sure not to leave out the Really Important Parts™:

git config user.master_password '<YOUR_MASTER_PASSWORD>'

git config user.social_security_number '<YOUR_SOCIAL_SECURITY_NUMBER>'

git config user.mothers_maiden_name '<YOUR_MOTHERS_MAIDEN_NAME>'Baby learns to make a mess

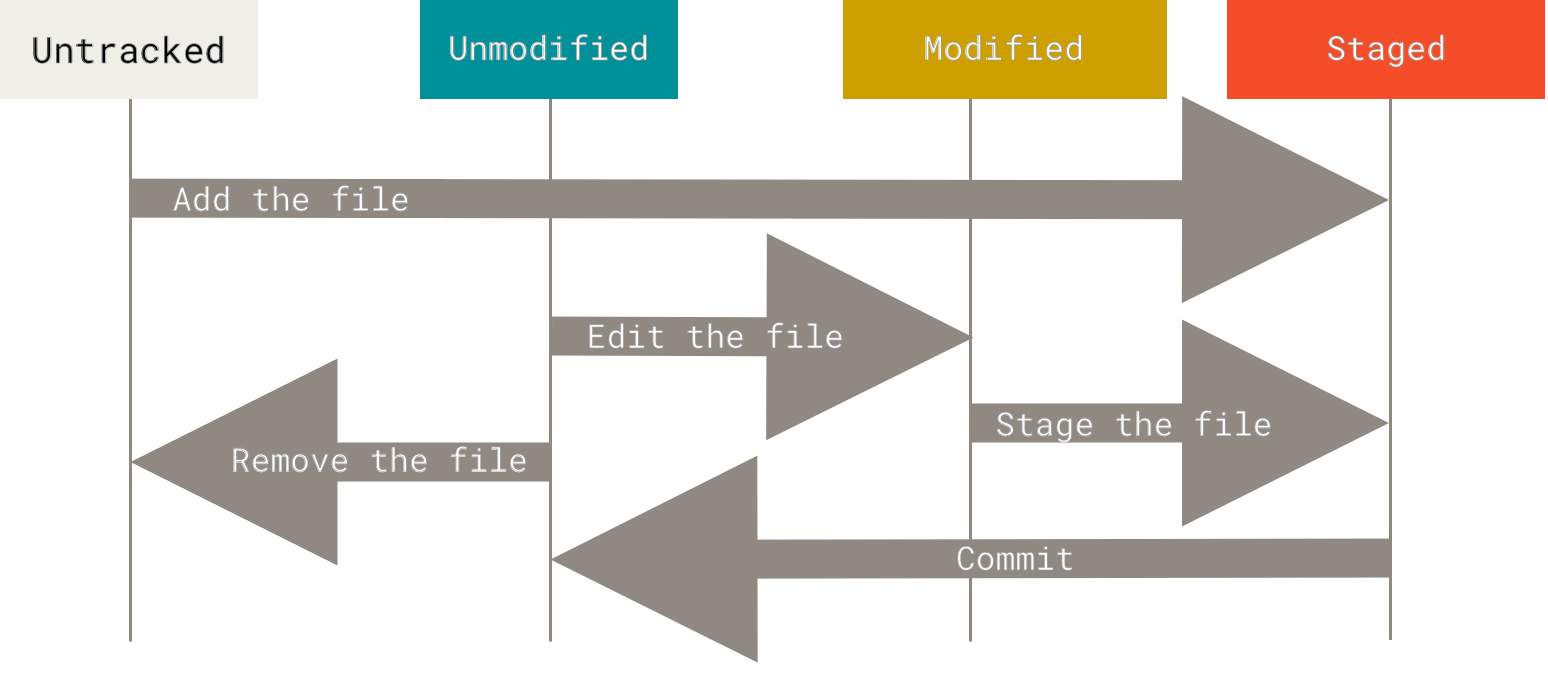

Below is the git file lifecycle. Take a moment to bask in its glory.

Each arrow above has a corresponding command below. Except for Edit the file. If you need my help with editing the file, get out of my goddamned class.

add

This command lets you Add the file and Stage the file, the difference only depending on whether the file was initially Untracked or Modified.

git add <SOME_FILE> <MAYBE_ANOTHER_FILE> <DONT_YOU_DARE_ADD_FOUR_FILES> <JUST_KIDDING_ITS_FINE>

git add <SOME_FILE_GLOB>

For <SOME_FILE_GLOB>, you can use:

- entire directories (

.) - wildcards (

*.md) - combinations (

subdirectory/*.txt) --allto stage everything that can be, you careless maniac

Binary Files

Because of how git works, it is generally considered bad practice to include huge files in git repositories, especially when they are non-text, i.e. binary. Common examples are multimedia files (assets) and executable files. There are many other options for storing and hosting these kinds of files. When in doubt about whether or not you should add a file to a git repository, ask your nearest data engineer for assistance.

reset

Files

This command serves as the reverse of Add the file and Stage the file, the

difference only depending on whether the file was initially Untracked or

Modified. It uses the same syntax as git add except with reset instead of

add.

Branches

This command also serves another purpose: changing where the current branch points to:

git reset <SOME_COMMIT_IDENTIFIER> # <SOME_COMMIT_IDENTIFIER> defaults to `HEAD`For example if your current HEAD is like this:

HEAD -> point-me-elsewhere -> 90fa092637f7c88e5e04efcba59a92f6ae2149b5

Running the following:

git reset 724b6076e3b1b0299344454f4ec59059cfbe8d75...will cause it to end up like this:

HEAD -> point-me-elsewhere -> 724b6076e3b1b0299344454f4ec59059cfbe8d75

BONUS: If you include the --hard option, this will also change the working

directory, meaning you can use this command to reverse Edit the file en masse!

rm

This command lets you Remove the file. Same syntax as git add.

Baby learns to write

commit

FINALLY we can commit something! Once you have some files staged, you can commit like so:

Simple

git commit -m "Your commit message"That's it! Your changes were bundled into a commit whose parent is your current

HEAD, then the equivalent of a git reset <NEW_COMMIT_HASH> happens.

Long form

If you have a particularly long commit message to write, you can do it like so:

git commitThis will open your editor where you can write the commit message. Once you close your editor, the commit will push through.

Amend

If you made an unforgivable mistake and need to edit the commit you're currently on, you can stage your fixes and do either of the following:

git commit --amend -m "Your improved commit message"git commit --amendThere are ways to edit entire histories, but that's for later.

Baby learns to read what it wrote

status

If you want to check the status of your repository, just run:

git statusA lot of command prompts already run this so that you can immediately tell if your repository is clean, has untracked files, has modified files, etc.

diff

If you want to see all the differences between between two commits, run:

git diff <ORIGIN_COMMIT> <TARGET_COMMIT> # <TARGET_COMMIT> defaults to `HEAD`merge

Now let's pretend that you have two branches, master and broken-feature. If

you want to update the master branch to have all the changes done on

broken-feature, just run the following while on the master branch:

git merge broken-featureIf git reports that the merge was successful, then you can rest easy. However, if git says there are conflicts that you have to resolve manually, we still have some work left to do.

Conflict resolution

If a merge fails, git will mark the conflicted sections in your files like so:

<<<<<<<

Changes made on the branch that is being merged into. In most cases,

this is the branch that I have currently checked out (i.e. HEAD).

=======

Changes made on the branch that is being merged in. This is often a

feature / topic branch.

>>>>>>>

To solve this problem, you will have to edit the file manually so that it's in

the ideal state after merging. This means removing the markers too. After that,

git add the modified files and run git commit to continue.

Cleanup

After merging, remember to clean up your obsolete branches:

git branch -d <YOUR_OBSOLETE_BRANCH>Baby learns to talk

This baby learned things in the weirdest order, but let's keep going. For the baby.

remote

We've talked about what remotes are for, but we haven't discussed how to manage them. Here are the most common commands you would use for that purpose:

-

List remotes:

git remote git remote -v # Also --verbose, lists all remotes and their URLs -

Add a remote:

git remote add <REMOTE_NAME> <REMOTE_URL>

-

Rename a remote:

git remote rename <OLD_REMOTE_NAME> <NEW_REMOTE_NAME>

-

Change a remote's URL:

git remote set-url <REMOTE_NAME> <NEW_URL>

fetch

If you want to update your remote-tracking branches, you can make fetch happen:

git fetch <REMOTE_NAME> # <REMOTE_NAME> defaults to `origin`You can also use the following options:

- If you have multiple remotes,

--allwill fetch from all of them. -p(also--prune) will delete all remote-tracking branches that have already been deleted on the remote.

merge

There is another dimension to the merge command. If you are on branch with a

corresponding remote-tracking branch, just running git merge will attempt to

merge the remote branch with your local as if you ran it like this:

git merge <REMOTE_NAME>/<BRANCH_NAME>pull

Pulling (git pull) is really just a shortcut for doing the following:

git fetch

git mergepush

To make a remote branch reflect your local branch:

git push <REMOTE_NAME> <BRANCH_NAME><REMOTE_NAME> will default to origin while <BRANCH_NAME> will default to

your current branch.

Use the force

Pushing will fail if there are any conflicts with the remote branch. If the branch is something other people are also working on, it's best to resolve those conflicts locally first before attempting another push. Otherwise, you may use force push:

git push <REMOTE_NAME> <BRANCH_NAME> -f # Also --forceOnly use this if you're confident that you're the only one working on this branch and that you won't lose any work from overwriting the remote branch.

Baby learns how to drive a car

*sniff* They grow up so fast. *tear*

.gitignore

Sometimes, running git status keeps telling you that there are untracked files but you know deep down in your heart that you will never EVER track those files, no matter how much they begged you to.

.

.

.

Just add them to a .gitignore file! ^__^

For example:

.gitignore

==========

secret.key

*.log

stash

Imagine that you're in the middle of working on something when all of a sudden an urgent bug is reported and it needs to be fixed yesterday. Do you just hopelessly throw away all of your work to switch over to fixing the bug?

Gee, I dunno, does the sun rise in the west?

Use git stash, ya dumdum!

- Run

git stashto move all of your mid-work changes into the stash. - Fix the super important bug.

- Celebrate fixing the bug by listening to some Electric Six.

- Go back to the branch from which you ran

git stash - Run

git stash popto restore the changes that you stashed earlier.

cherry-pick

You want <COMMIT_A> replayed on top of <COMMIT_B>? No problem!

git checkout <COMMIT_B>

git cherry-pick <COMMIT_A><COMMIT_A> and <COMMIT_B> can be any commit identifier.

revert

Sometimes, your mistakes are too deep in the history tree for you to use git commit --amend. In these cases, you can use git revert <COMMIT_IDENTIFIER> to

create a new commit that effectively does the exact opposite of what

<COMMIT_IDENTIFIER> did.

Baby learns how to do brain surgery

Baby no more, adult yes less.

rebase

Rebasing is the art of changing the course of history. It is also very useful in keeping the history linear, which is helpful in preserving certain bits of information and making diagnosis and debugging easier.

The basic use case of rebase is when you want to replay all of the changes on a branch onto another branch without creating a new commit. This is done like so:

git checkout <BRANCH_YOU_WANT_TO_MERGE>

git rebase <BRANCH_YOU_WANT_TO_MERGE_INTO>When this is done before merging, what is called a "fast-forward" is possible, meaning no additional commit for the merge has to be created, preserving a linear history. Some complications may also arise from merge commits that have two parents, which is common for unrebased branches.

This doesn't always run free of conflicts, however, and you might be asked to

resolve some manually. To do so, just stage your changes and git rebase --continue. Or git rebase --abort if you are a scared little baby.

Another mode is to use rebase interactively like so:

git rebase -i # Also --interactiveThis gives even more control, allowing you to reorder, drop, and modify entire commits. Use with caution.

bisect

If you are trying to figure out which commit introduced a particular bug, git bisect is your best friend. This tool basically lets you do a binary search

over a long history tree to pinpoint the offending commit.

- Run

git bisect start - Check out a commit that you know has the bug and run

git bisect bad - Check out a commit that you know is free of the bug and run

git bisect good

Git will then continuously ask you to evaluate commits with either git bisect good or git bisect bad until it points out the first bad commit.

Help

You're gonna need it.