Now, it's time to take your knowledge one step further. You're going to marry your knowledge of layout with your knowledge of asynchronous programming and data structures to interact with a server that shows you the contents of files on your computer. From this point forward, most projects that you do will combine all of the knowledge that you've used up to this point. The projects will ask you to practice many skills in combination.

The story: This project mimics something you will experience while on the job. There's some old version of some software running, and the users want something newer and better. This project has you "replace" an existing software application that browsers a file system with one that lets the users interact better with the file system as well as improving information density and throughput.

This project will have a tree, both visually and in memory, that stores the representation of files and directories on your computer's hard drive in the browser so that you can interact with it.

Download the starter project from

https://github.com/appacademy-starters/responsive-design-file-browser-starter.

It comes with a server that you will interact with from your code via fetch

statements.

Run npm install to install the dependencies.

Go ahead and start the server by typing npm start in the starter project.

You'll see that the program prints out the following message.

Your browser.html and API served from http://localhost:3001

Browse the files statically at http://localhost:3000

That's right, it started two Web sites. The first one is at http://localhost:3000. Click on that link. It will open the existing version of the file browser. It is fully functional, but basic in its presentation and interactions.

Continuing the story, the users have clamored for something "more modern" as well as being able to see files and directories in a tree next to the contents and information. That's what you're going to give them!

The directory structure of the project looks like this.

starter/

├── directory-browsed/

├── server/

└── your-code/

├── icons/

├── browser.html

└── style/

The directory-browsed directory is where the server will read directory contents from. If it's in that directory, then you should be able to see it in the application that you write. Right now, it contains a lot of files from an open-sourced book called JavaScript Allonge, Sixth Edition, by Reg Braithwaite. (https://github.com/raganwald/javascript-allonge-six)

The server directory contains the node server that powers the application and serves your page. It starts two servers:

- http://localhost:3000 - this is a built-in and rudimentary file browser that your application would replace

- http://localhost:3001 - this will server your code and serve your API requests

when you

fetchdata

The your-code directory contains browser.html, the file in which you should put your HTML. You can create all the CSS and JavaScript files you want in the your-code directory and link them the way that you would normally do it. The server will serve them for your pleasure.

The your-code directory also contains icons and a CSS reset file.

TODO: Explain final layout

Your code will make calls to an Application Programming Interface (API), which for this case, is just a fancy way of saying "a place to get data from". The following table shows the different ways that you can call the API. All URLs in the first column will be for the server http://localhost:3001. All of the paths are relative to the directory-browsed directory.

| URL | HTTP Verb | What it does |

|---|---|---|

| /api/path/«dir-path» | GET | This returns the list of files and directories in «dir-path» |

| /api/file/«file-path» | GET | Returns the contents of the file at «file-path» |

| /api/entry/«file-path» | PATCH | Moves a file from one location to another |

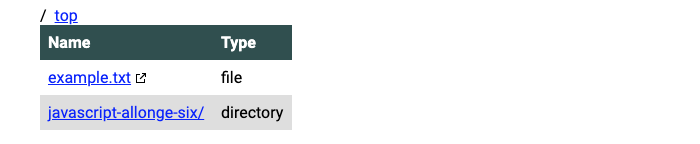

Each step of the project will go into depth about what you should do to interact with those API endpoints. For example, directory-browsed has the following entries to two levels deep. (There are a lot more files under javascript-allonge-six/manuscript/.)

directory-browsed/

├── example.txt

└── javascript-allonge-six/

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── manuscript/

└── need-to-be-fixed

Here's an example of how you would call the API to retrieve the contents of a directory. Let's say you added the following HTML block to your-browser.html.

<script>

fetch('/api/path/javascript-allonge-six/')

.then(response => response.json())

.then(filelist => console.log(filelist);

</script>The server would get the path /api/path/javascript-allonge-six/ as

part of your request.

The /api/path part is there for the server to know that you're using the API

and want it to look at the contents of a directory at the path that comes after

/api/path/.

The path that comes after /api/path is /javascript-allonge-six/.

The server looks in the directory-browsed directory for

/javascript-allonge-six/, finds it, and returns the list of files

to your fetch call. Then we use the response.json() to grab the list of

files in the directory, and finally, print it to the console.

Whatever path you put after /api/path, it's going to try to read the list

of files from that directory and return them. If the directory doesn't exist (or

something bad happens), then your code will get an appropriate HTTP status code

that indicates the error, like 404.

Remember that you will need to check

response.okinfetchcalls to catch things like 404 errors.)