These are materials for a lightning talk given at SyncHerts by Paul Dixon on 14 Jan 2016.

The slides from the talk are available via SlideShare

The object of the talk was inspire at least one person to try their hand at Atari 2600 programming just for the interesting challenges it presents. If you're reading this, I'm glad it piqued your interest - tweet @lordelph to let me know how you get on!

- stella - a multi-platform Atari VCS emulator. This is where you'll play and debug your games

- dasm - a macro assember - this turns our 6507 assembly language into a binary file we can run on an Atari emulator like stella.

- make or similar is handy if you're already familiar with Makefiles, but you can get by perfectly well without it for a simple project.

- 2600intro - this very repository - the syncherts folder contains all the code used to generate the example in the presentation.

- It helps if you can use editor for which you can find some syntax colouring support for 6502 assember - I personally like using Sublime

- Stella Programmers Guide by Steve Wright all the gory details you could need.

- Atari 2600 for Newbies by Andrew Davie an excellent 25 part tutorial taking you through every aspect of writing code for the Atari 2600

- 2600 101 by Kirk Israel another great tutorial written by someone writing as they learn.

- Racing the Beam is an absorbing book going into both technical and cultural elements of the Atari VCS.

- Kirk Israel's playfield editor

The talk was limited to 5 mins, and I'll waste 90 seconds just introducing myself and the console. So I've got about 3 minutes to try and illustrate the pleasure and pain of developing for the Atari VCS!

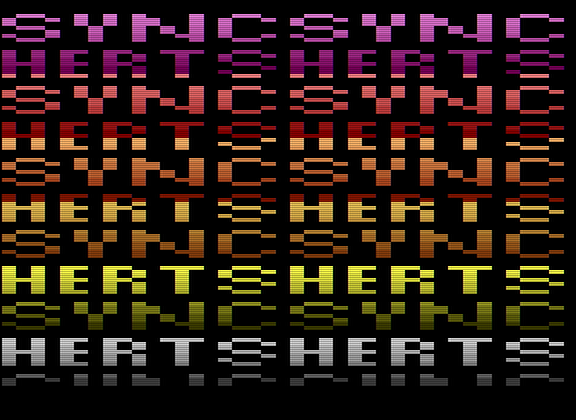

What we're going to do is make the background, or playfield, display this:

All the code is in the syncherts folder of this repository.

Our starting point will be the excellent template in Kirk Israel's tutorial.

This template clears the Atari's memory and sets everything up with predictable values, and shows how main game loop operates.

As each scanline is drawn, we can control 20 bits which affect the playfield, turning a 'pixel' (a vague concept on the Atari) or or off in the left half of the display. The right half uses the same bits, which can be mirrored. So this means we've got a resolution of 40x192 to play with.

I designed the 'SYNCHERTS' playfield using this playfield editor, as the bit pattern isn't entirely intuitive to layout by hand. This editor will spit out some literals you can include in your assembly. I've placed them after the game code, and they have the labels PFData0, PFData1, PFData2.

These correspond to the PF0, PF1 an PF2 playfield registers. Here's a shortened example showing the first two lines of data

PFData0

.byte #%00000000

.byte #%01010000

PFData1

.byte #%00000000

.byte #%11010100

PFData2

.byte #%00000000

.byte #%00110001

We have 19 lines of playfield data, and before we enter our main loop iterating over each scanline, we set the X register to 18. We're going to count down from 18 to 0, and use the X register to index into those arrays of playfield data.

Counting down means our data must be stored upside down, something the playfield editor will do for you automatically.

Sheer economy. We do not have many cycles available to set up the scanline, so the fewer instructions the better. When we count down, we use the DEX instruction to decrement the X register. This will set the processors 'Z' (zero) flag when it reaches zero, and we can use the 'BNE' instruction to branch if the Z flag hasn't been set.

If we counted up from zero, we'd need an extra comparison instruction, and as you'll see, we can't afford many cycles.

So, inside the scanline loop, here's how we load the playfield registers using the X register as the offset into our data arrays

; load our playfield data cycle count!

LDA PFData0,X ;0+4 = 4

STA PF0 ;4+3 = 7

LDA PFData1,X ;7+4 = 11

STA PF1 ;11+3 = 14

LDA PFData2,X ;14+4 = 18

STA PF2 ;18+3 = 21

DEX ;21+2 = 23

BNE MorePlayfield ;23+3 = 26 (if branch taken)

LDX #18 ;reset playfield counter ;25+2 = 27

MorePlayfield

Here we load the A register with the value at memory address PFData0+X, then we store that value in the PF0 location. We do the same for the PF1 and PF2 registers.

Then we lower our X register, and if we've reached the end, we reset it back to 18. Note this means we never actually use the first value indexed by zero, but in this simple example we'll live with the wasted space!

When programming the Atari 2600, you need to be constantly aware of how many cycles you've used. So let's see what our playfield setting code is going to cost us on each scanline.

Here is a guide to cycle counting by Nick Bensema. We can use that to determine our LDA PFData0,X and STA PF0 7 cycles. We do that 3 times, bringing us up to 21 cycles. The DEX adds 2 more, bring us to 23 cycles.

Our branch, if taken (which is most of the time) is 3 cycles, which gives us a grand total of 26 cycles. When we reach the end of the playfield data loop, we'll incur 2 cycles for the BNE and 2 more for the LDX, so the longest our code fragment takes is 27 cycles.

We actually only have 22 cycles from the end of the last scanline before the new one starts!

The only reason this code works is because by the time we've used 22 cycles, we've actually got the PF0 and PF1 registers set up - it will be another 16 cycles before it needs to read PF2.

If we re-arrange the code so that we write PF2, PF1 and then PF0, we'll see the playfield design get's torn, as the PF0 value is written too "late", and appears on the scanline below where it should.

Each scanline takes 160 color clocks, which runs on clock 3x faster than the CPU, so after the 22 cycles we do have 53 cycles in which we can do more work in preparation for the next cycle.

This gives a taste of what's involved, but as well as the playfield, you've got the movement of player sprites, 'missiles' and a 'ball' to content with, as well as reading player joystick inputs and playing back sounds!

If it sounds impossible, then it will give you new appreciation of how incredibly programmed these early games were.

But if you like a challenge, writing your own Atari code, even a simple demo like this one, can be quite rewarding.