When I mention versioning, a lot of people assume I'm talking about how someone specifies the version of a RESTful API that he or she wants to consume. Namely, URI vs content negotiation. That's not what this article is about, but it is requisite to remember that if you are asking your consumers specify which version they want, you are presumably offering (and to some degree maintaining) multiple versions at a time. If you only offered one version at a time, consumers wouldn't have to specify which one they want. That would be silly, because there's only one choice.

Maintaining many released versions of an API at a time is what this article is about. Specifically, how to do this with git from a release management point of view. That means seeing both the trees and the forest among your git branches. (You see what I did there with the branch pun?)

For the purpose of this article, we assume that the git repository only contains the RESTful API specification (i.e. RAML, Swagger or JSON API files) As such, I'm going focus only on things worthy of major or minor releases according to Semantic Versioning (aka SemVer). Bug fixes which increment the patch number are related to the incorrect implementation of an unchanged specification, and therefore out of scope here.

When I mention git branching strategies, a lot of people assume I'm talking about the Gitflow workflow. Some propose Gitflow as a solution for managing releases, or they describe the Feature Branch workflow and call it Gitflow. Occasionally I'll even get a bit of mansplaining about what a branch is. So let's clear the air.

In a nutshell, the Feature Branch workflow dictates that feature-related work should happen on a branch dedicated for that purpose. There is often a common nomenclature for naming these branches. This almost seems like common sense nowadays, because the alternative is that everyone works in the master branch all the time. An API specification is no exception to this principle: its changes should be feature-driven and reviewed/tested before being merged. Feature branches are good.

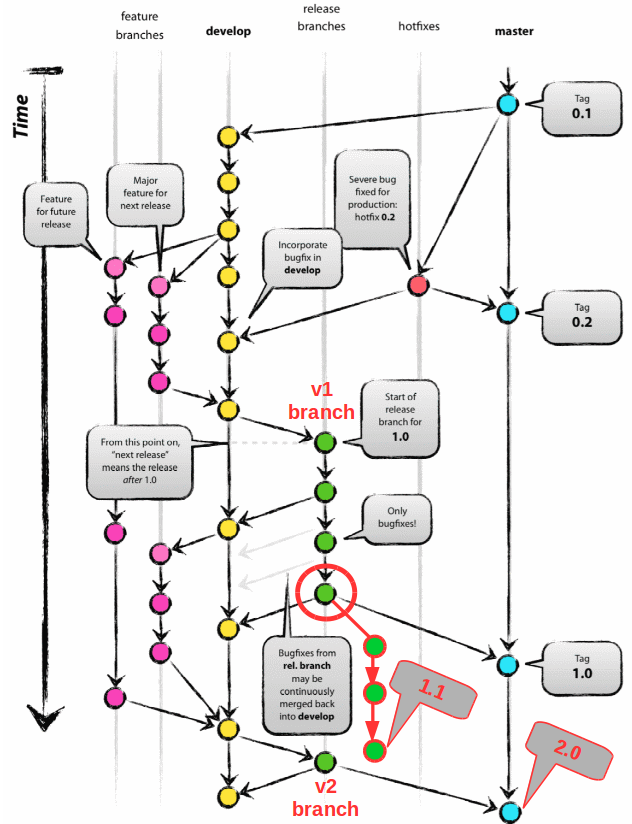

The Gitflow workflow zooms out a bit, and defines a strict branching model for releasing projects. Vincent Driessen introduces this model in his blog post. This strategy relies on two branches, master and develop, which have an infinite lifetime. Release branches exist temporarily and are deleted after merging into master. This is where you realize that Gitflow is perfect for many applications, as long as they only intend to release and maintain one version of their project at a time. master represents the current release, and develop represents the forthcoming one. You can hotfix the current release, and tags represent older releases, but at that point the code is all on the same master branch.

Given this, can you use Gitflow to track, deploy and troubleshoot multiple releases at a time? Yes. Can you use Gitflow to fix or enhance many releases at a time? No. We need a different model.

When I mention enhancing older releases, a lot of people look at me like I'm crazy. “Why would you ever do that?” they ask, as though I'm the world's biggest sucker. Here's where you need to understand why that is necessary (common, even) in the world of RESTful APIs.

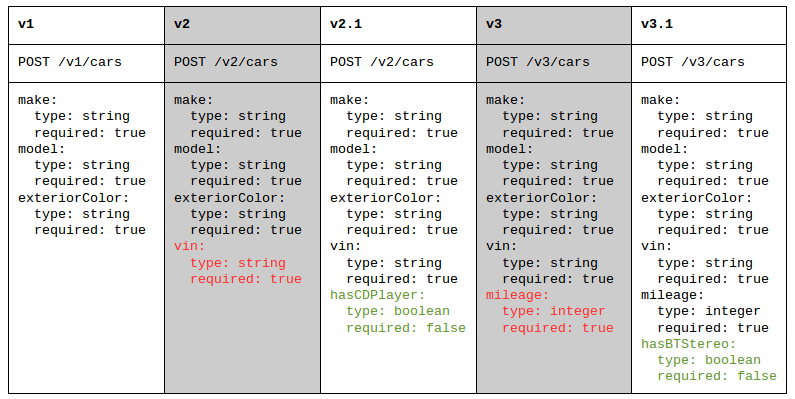

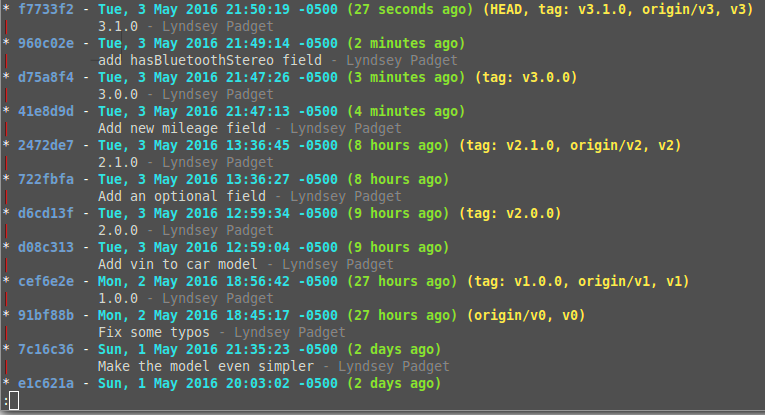

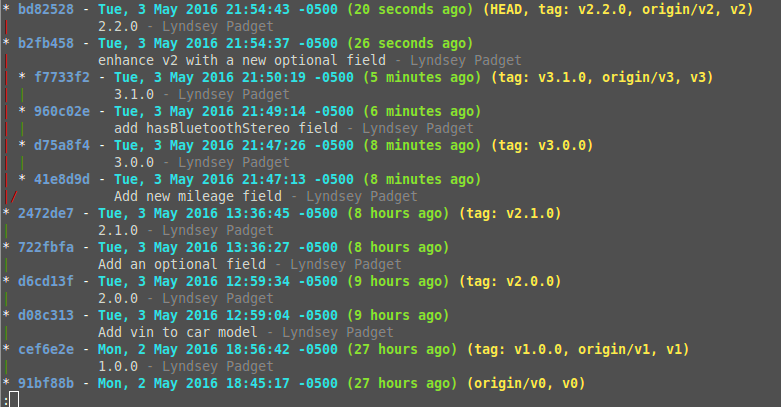

The following chart shows how an endpoint can change over time. Let's say you maintain a RESTful API for managing cars at a dealership. All of these are POST calls that accept a car model. I've defined this model in RAML, but I've only included the properties here for brevity.

If you're interested, here's how this history played out:

- In v2, it became required to specify a vin when creating a car object. Without one, the request would fail. This is a breaking change, so the major version is bumped.

- In v2.1, a nice-to-have feature was implemented, which introduced the option to indicate whether or not the car has a CD player. If you omit this field, the POST call will still succeed. This is a passive change, so the minor version is bumped. v2 is no longer supported, because consumers using v2 can now use v2.1 without changing their code.

- In v3, the mileage field was introduced. Like vin, this is a breaking change. But there's another subtle change here: the optional hasCDPlayer field is no longer supported/accepted (because the only person who still uses CDs is my grandma). Whether or not that is a breaking or passive change depends on how the system behaves when it is given. You can throw an error - making it break - or you can silently ignore the now-unrecognized field. In this case, I recommend the latter because the field is optional, and you may want to release v2.2 without it.

- In v3.1, yet another optional field was added; bluetooth is all the rage now. Again, v3 is no longer supported because consumers who used it can now seamlessly use v3.1 instead. That's what makes v3.1 passive, by definition.

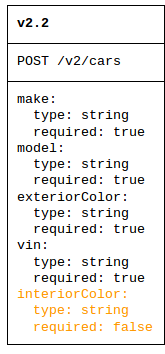

Let's say that the tablet version of the dealership's car-searching app uses v2.1 and the desktop version uses v3.1. The salesmen at the dealership prefer using tablets, because they can quickly manage car inventory without leaving the customer on the floor. Now, the dealership would like the ability to add/search cars by interior color on the tablet app. This is a request to enhance v2.1 by adding a new optional field called interiorColor, thus making v2.2.

Should this be allowed? Some might say no – only introduce enhancements in the latest release and tell the client to upgrade. This seems unaccomodating. This client here is a car dealership, and they don't have the time or money for an entire v3 upgrade. They just want to add one little field to see if they can sell more cars.

In a perfect world, everyone would be on the latest version. But we don't live in a perfect world, which is why we support multiple versions in the first place. Perhaps such enhancements are experimental business strategies that can revolutionize or devastate the client's sales. I believe it's better to figure that out on a passive older release, so you can decide whether or not to include it in the next version.

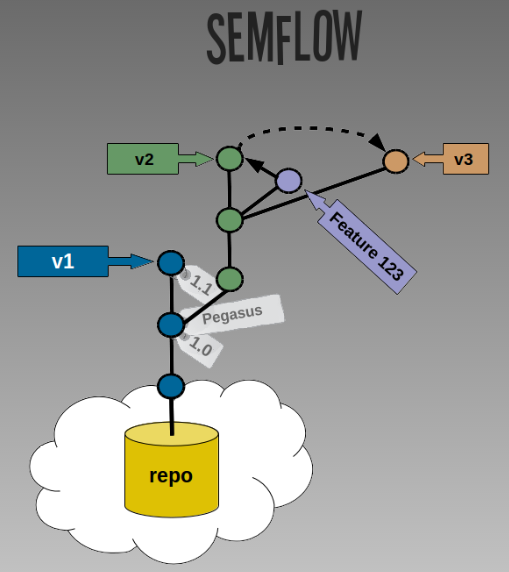

The basic premise of the SemVer workflow is to keep each major release in its own branch.

master is not special. When you create a new git repository, master is the just the recommended name for the first trunk-like branch you will create. master is also the default branch. However, until you make the first commit, the first branch doesn’t even exist.

Recall that master represents the last release and develop represents the forthcoming one. If you were really set on keeping those branch names, you could still use many aspects of Gitflow, but you would keep release branches indefinitely. When you release a new major version, it is tagged and merged into master and develop. When you release a new minor version, it is branched from the appropriate release branch.

This works, but personally, I think it’s confusing. If we’re going to maintain branches for each major release, I would rather each branch name be explicit. I don’t like having to wonder what major version these branches contain.

In a SemVer workflow, master and develop do not exist. The name of the “trunk” branch is v0 or v1. Minor releases get a tag (i.e. 1.1.0), while major versions get a tag (i.e. 2.0.0) and a new branch (i.e. v2). Code on each branch’s HEAD (the leaves in the tree) can still be hotfixed if necessary, and enhanced with code from feature branches.

This approach becomes especially useful when you have a feature off of a v(N) branch that you would like to merge into both v(N) and v(N+1). When the feature is complete, you can squash that branch’s commits and cherry-pick them over to other branches as needed, resolving conflicts if necessary. This might seem unlikely, but occasionally you begin a feature expecting both its need and impact to be isolated, but discover later that it could/should be applied more broadly.

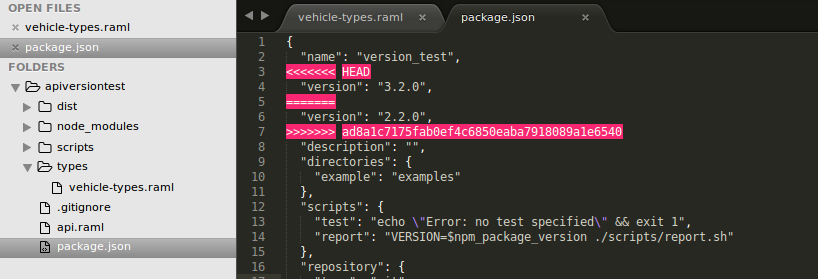

For this reason, it’s recommended that you keep a set of code or specification changes separate from the commit that actually bumps the version number or applies a tag. In my case, I track the version number in the package.json file, and I don’t want that change to come along with the RAML modifications I want to apply in a different branch. Failing to keep these separate will result in a post cherry-pick conflict resolution like this:

Let’s say I want to bring the vehicle’s interiorColor field into version 3 of the API. In this example, I’m on the v3 branch and cherry-picking a commit from the v2 branch. If I wasn’t paying close attention, I might choose the wrong version, and things would get very ugly.

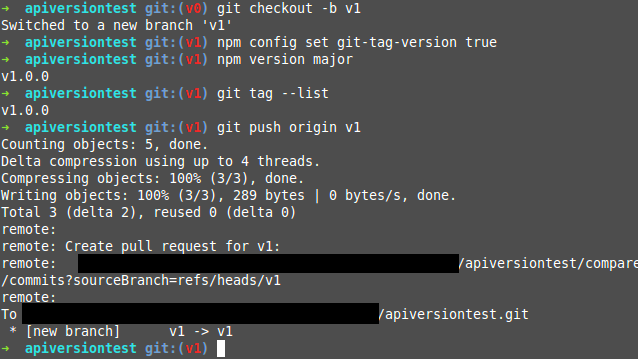

First, we'll create a branch that represents our first “beta” release – v0. This branch contains what will soon become v1 of the API. (If you've already checked in code to master, you can rename it to v0 and delete the master branch!) Remember to set the default branch to v0 in your [Stash] repository settings:

When you're ready to release version 1 of your API, you create a new branch. You can use npm version to tell the project how to increment itself according to SemVer rules, which will create an isolated commit with a tag. (Note that I should have pushed with tags here: git push origin v1 --tags).

In this case, the RAML itself can have a version number, but I removed it and will rely on the package.json instead. (Scripts can help sync the two - the goal is to have a single source of truth for the version number.)

If I keep adding to the API spec like the example chart above indicates, my tree looks something like this:

This represents typical development where no minor updates are made to older releases. Notice how it looks linear, even though we’ve made branches for each major version. Then, when we update the v2 branch with an enhancement (v2.2) the tree looks like this:

Git is a powerful and flexible tool. Standard workflows are fundamental in helping teams keep code organized, but they should never box you in. In general, the Feature Branch and Gitflow workflows are fantastic, but you can adapt them to the needs of your project and team. I see the SemVer workflow as one such adaptation. It just so happens that this model applies nicely to multi-versioned RESTful APIs.