The road to be a professional is hard, it's the famous jr-to-sr path. The reality is that you can get there.

- Language Knowledge

- IDE Knowledge

- Best Practices

- Have a toolbox

- Ethics and professionalism

- Experience

JavaScript, as other languages, has a set of fundamentals that are a must-be to start with them. Furthermore, there are non-fundamental topics that are a nice-to learn but not needed at the beginning. The non-fundamentals are great to understand how the technology works and stop believing it's just magic.

- Promises (In a super pro way)

- Getters & Setters in Classes

- Proxies

- Generators

- JavaScript Engine

- Prototype Inheritance

- Event loop

- Design patterns

- Initialize the project. That is, create a

package.jsonfile with the project info (some metadata) and the dependencies manifest.

npm init -y- Install a development server.

npm install -D live-serverIn package.json file a script can be created to associate the live-server with some npm command.

// package.json

// ...

"scripts": {

"start": "live-server"

},

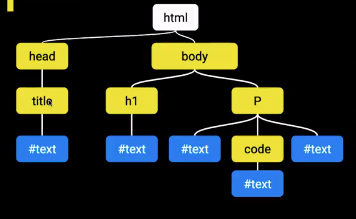

// ...Scripts are always linked in a HTML document. The HTML document is sent to the browser, and the browser starts interpreting each row of the HTML document, assembling the DOM (Document Object Model). The DOM is structured with a tree architecture.

When the browser finished the interpretation of the DOM, the DOMContentLoadedevent is triggered.

There are some ways to load a <script> tag while the DOM is being processed.

-

Code embedded inside a simple

<script>tag.<script> const button = document.querySelector(".button"); button.addEventListener("click", function foo() {console.log("bar");}); </script>

For this case, the DOM load is stopped while the browser interprets and executes the JS script.

So it's important to have in mind that the only objects available in the DOM are those that have been already processed by the browser before the script execution. So, to avoid problems regarding the

-

Code imported via

srcin a simple<script>tag.<script src="https://some-url/jquery.js"></script>

Similar to the previous case, the DOM load is stopped while the browser fetches and executes the JS script.

-

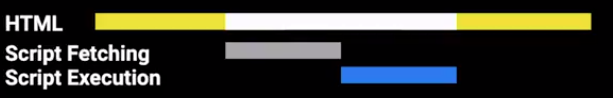

Using

async<script async src="https://some-url/jquery.js"></script>

Adding the

asyncattribute to the script, the DOM load is not interrupted while the browser fetches the script, but it is stopped when it is executed. -

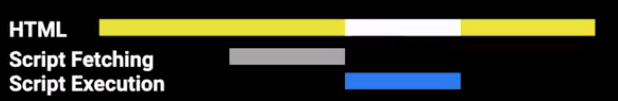

Using

defer<script defer src="https://some-url/jquery.js"></script>

Adding the

deferattribute to the script, the DOM load is not interrupted while the browser fetches the script. And the execution is done only at the end, when the DOM load is finished.

The scope of a variable represents the lifetime that a variable will be available in the code. Javascript has had a poor scoping system, but with the latest EcmaScript implementations (ES6+), this has been improved.

Global scope refers to everything that is defined outside a function or outside a block.

<script>

var message = "Hello";

// in the browser console this variable will be attached to window

// window.message will return "Hello"

</script>The danger of having a global scope is that there is no restriction to do anything and mistakes can be made. For example, if an external library is being imported, any variable defined in the global scope in that library can be overwritten by mistake.

When a function is defined, a new scope is created inside of it.

function printNumbers() {

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) { // i is defined withing the scope of the function

setTimeout(function () { // the loop will end before the timeOut event is triggered

console.log(i); // when the event is finally triggered, the value of i will be 10

}, 100)

};

};

printNumbers(); // will print the number 10 ten times.To catch and remember the value of i on every step of the iteration, a new function scope inside the current function scope can be defined:

function printNumbers() {

var i; // i is defined withing the scope of the function

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

function printTimeoutNumber(n) { // a new scope inside the function is defined

setTimeout(function () {

console.log(n);

}, 100)

}

printTimeoutNumber(i); // i is passed to the new scope as an argument

};

};

printNumbers(); // will print the numbers 0 to 9.A block in JS is everything wrapped by { }. This is introduced in ES6, and the idea is that let and const ways to declare variables are making them valid only within the scope it is being used, instead of var, which applies all the other scope rules. So the previous code just works if i is defined with let instead of var.

function printNumbers() {

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) { // i is defined withing the scope of the function

setTimeout(function () { // but here a new block scope is created

console.log(i); // so the value of i is caught and reminded.

}, 100)

};

};

printNumbers(); // will print the numbers 0 to 9.Modules are JS files that are exported and imported. A module scope limits the life of the variable only within the file.

<script type="module">

var a = "helloo"

</script>

<script>

console.log(a) // will return undefined

</script>In the ES6 modules, the export command specifies the variable(s) that can be called (with import) outside the module.

this refers the object on which the code chunk is being executed

console.log(this) // returns the Window Objectfunction whoIsThis() {

console.log(this)

}

whoIsThis(); // still returns the window objectBut with the strict mode of ES6,

function whoIsThis() {

'use strict';

console.log(this)

}

whoIsThis(); // returns undefinedThe strict mode is simply some functionality that JS engine implements to modify some behaviors that are not very intuitive.

const person = {

name: "Miguel",

greet: console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.name}`)

}

person.greet() // returns "Hey! I'm Miguel"Continuing the above code, if somehow the method is passed to a new global function, then:

const myFunction = person.greet;

myFunction() // returns "Hey! I'm"this in classes will refer to the class instance, not the prototype object.

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Person.prototype.greet = function() {

console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.name}`);

}

const guy = new Person("Jerry");

guy.greet(); // returns "Hey! I'm Jerry"call, apply and bind all of them specify the object on which this will be referring to inside a function.

callwill call the function, attach the object referral tothis, and passes additional arguments to the function separated by commas.applywill call the function, attach the object referral tothis, and passes additional arguments to the function but wrapped inside an array.bindwill attach the object referral tothisand returns a new function with that functionality. This new function can be saved in a new variable and used later whenever needed.

function walk(distance, direction) {

console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}. I walked ${distance} mts to the ${direction}`);

}

const guy = {

firstName: "Jerry",

lastName: "Griffin"

}

// these all return "Hey! I'm Jerry Griffin. I walked 400 mts to the north"

// using call

walk.call(guy, 400, "north");

// using apply

walk.apply(guy, [400, "north"]);

// using bind

const guyWalk = walk.bind(guy);

guyWalk(400, "north");This is almost a unique JS topic, that changes the way we deal with classes and objects.

-

Simple objects

const zelda = { name: "Zelda" } zelda.greet = function() { console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.name}`) } const link = { name: "Link" } link.greet = function() { console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.name}`) }

-

In order to avoid DRY, we can create a function that returns a hero object:

function Hero(name) { const hero = { name: name } hero.greet = function() { console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.name}`) } return hero; } const zelda = Hero("Zelda"); const link = Hero("Link");

-

One problem still: The

greetfunction is defined every time a new hero is created. We can do something to avoid this:const heroMethods = { greet: function() { console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.name}`) } } function Hero(name) { const hero = { name: name } hero.greet = heroMethods.greet; return hero; } const zelda = Hero("Zelda"); const link = Hero("Link");

-

This can be refactored using

Object.create(). This method receives an object as an argument and appends this object to the prototype of a new one. That's how inheritance works.. The prototype of an object is appended to the prototype of the other and so on :).const heroMethods = { greet: function() { console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.name}`) } } function Hero(name) { const hero Object.create(heroMethods); hero.name = name; return hero; } const zelda = Hero("Zelda"); const link = Hero("Link");

-

Adding some syntactic sugar. With

new ClassName()the above code can be replaced with this:function Hero(name) { this.name = name } Hero.prototype.greet = function() { console.log(`Hey! I'm ${this.name}`) } const zelda = new Hero('Zelda') const link = new Hero('Link')

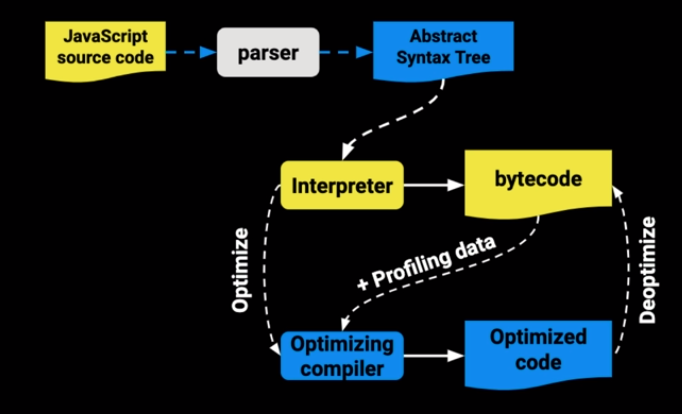

JS is an interpreted language.

Initially JS arrived along with Netscape browser. It was when Google released Google Chrome, that Google reinvented the way that Js engines worked.