Go course

Advantages of go

- Code runs fast (why it runs fast)

- Garbage collector, some other languages that run fast as Go does they don't have garbage collection

- Simpler object, object orientation is a little simplified as compared with other languages

- efficient concurrency implementation built into language

Code runs fast

Three categories of languages:

- machine language - low level language and it's directly executed on the CPU (simple, small test. e.g. add, move, read from registry etc..)

- assembly language - equivalent to machine language but easier to read. Map one-to-one the machine language (not completely but very close) equivalent, but you can read it because it's english. When you want to something very fast and really efficiently then you'll write it directly in assembly language.

- high level language - everything else, they are much easier to use. Go is high level language!

All software must be translated into the machine language of processor

If you've got a processor, i7 or whatever processor you're working with, that processor does not know C or Java or

Python or Go or C++ or any of those, right?

All it knows is its own machine language, say x86 machine language. So C, Python, Java or whatever it is, has to be

translated. There is software translation step that has to go on:

- Compiled - high level language to machine code happened one time before you execute the code. Translation occurs once, and when you run the code you are just running the machine code directly.

- interpreted - instructions are translated while the code is excuted. So the translations occurs every time you run the Python code and so that slows you down.

Compiled code is generally faster to execute. Interpreters make coding easier: manage memory automatically and infer variable types.

Go is a good compromise between compiled and interpreted languages, it is compiled language but it has some good features of interpreted languages.

Garbage collection

Automatic memory management

- where should memory be allocated?

- when can memory be deallocated?

Manual memory management is hard

- Deallocated too early, false memory access

- Deallocated too late, wasted memory

Go has garbage collector, downside is that it slows down exection a bit, but it is an efficient garbage collector.

Objects

Go language is object-oriented -> weakly object-oriented. It implements objects but they have fewer features than you would see in another object-oriented language.

Object-oriented

- Object-oriented programming is for code organization (encapsulation).

- Group code together data and function which are related.

- User-defined type which is specific to an application.

- generic type ->

intshave data (the number) and functions (*, +, - etc.) - e.g. 3d geomtric applcication ->

point(x, y, z) { DistToOrigin(), Quadrant() }

difference between object and class

- generic type ->

Object in Go

- does not use

classbut usestructs - simplified implementation of classes

- no inheritance

- no constructors

- no generics

This makes it easier to code and it makes it efficient to run. But if you like these features this is a disadvantage.

Concurrency

There are built-in constructs in the language that make it easy to use concurrency.

A lot of motivation for concurrency comes from the need for speed, not all.

How concurrency get around these performance limitations.

Performance limitation of computers

- Moore's Law used to help performance

number of transistors on a chip doubles every 18 months. - more transistors used to lead to higher clock frequencies

Programmers would get lazy, because they knew that pretty soon hardware people would double the number of transistors and fixed all their problems for them, but that si not happening anymore, because Moore's Law had to slow down. - Power/temperature constraints limit clock frequency now

So you can't keep increasing the clock rates.

How do you get performance improvement even though you can't just crank up the clock?

Parallelism

- Increase number of cores

- you can perform multiple tasks at the same time

- it does not necessarily improve your latency but your throughput will improve (potentially)

🤞

- it does not necessarily improve your latency but your throughput will improve (potentially)

- Difficult with parallelism

- when do tasks start/stop?

- what if one task needs data from another task? How does this data transfer occur?

- Do tasks conflicts in memory?

You do not want one task to write to its variable A and that overrides vairable B of another task. Code that can be executed in parallel can be difficult.

Concurrency programming

- Concurrency is management of multiple tasks at the same time

They might not actually be executed at the same time (e.g. single core processor) but they are alive at the same time. So they could be executed at the same time if you had the resource. - Key requirement for large systems

You want to be able to consider 20 things at one time. - Concurrent programming enables parallelism

- Management of task execution

- Communication between tasks

- Synchronization between tasks

So You can not just take a piece of regular code and say oaky I'm going to run it on 5 cores, that won't work. The programmer has to decide hot to partition this code (I want this data here and this data there etc.).

The program is making these decisions that allow these things to run in parallel.

Concurrency in go

- Go includes concurrency primitives

- Goroutines represent concurrent tasks

- Channels are used to communicate between tasks

- Select enables task synchronization

- Concurrency primitives are efficient and easy to use

Install Go

brew install go

Workspaces and packages

Workspace

Workspace is a directory where your Go stuff will go.

- hierarchy of directories

- Common organization is good for sharing

You never programming alone, you can work with people all over the place, and they have to be able to work with your code (merge, link, review, edit). So it is nice have a common standardized organization of your files. - Three subdirectories

- src - Contains source code files

- pkg - Contains packages (libraries) Packages that you are going to link in that you need

- bin - Contains executables your compiled executables

- Directory hierarchy is recommended, not enforced.

- Workspace directory defined by GOPATH environment variable.

Packages

- Group of related files

- Each package can be imported by other packages

- The first line of file names the package

package mypackageimport ( mypackage )

- There must be one package called

main

That's where the execution starts. - Building the main package generate an executable program

when you build a non main package does not make it executable - Main package needs have a function called

main() main()is where code execution starts

Go tool

import

importkeyword is used to access other packages- Go standard library includes many packages

i.e. "fmt" - printf statement - Searches directories spefified by

GOROOTandGOPATHif you import packages from some other place you have to changeGOROOTandGOPATHso that it can find them

Go Tool (CLI)

- Tool to manage Go source code

- Several commands

go build- compiles the program

arguments can be a list of packages ora a list of.gofiles creates an executable for the main package, same name as the first.gofilego doc- prints documentation for a packagego fmt- format source code filesgo get- download packages and install themgo list- list all the install packagesgo run- compiles go files and runs the executablego test- runs tests using files ending in_test.go

Variables

-

names must start with a letter

-

any number of letters, digits or underscores

-

case sensitive

-

don't use keywords (

if,case,packageetc..) -

data stored in memory

-

must have a name and a type.

var x int -

can declare many on the same line

var x, y int -

type defined the values a variable may take and operation that can be performed on it

-

How much space in memory you are going to need to allocate for this variable

- integer

- floating point integer division is different from floating point division (depends on hardware)

- Strings

-

You can define an alias, an alternative name for a type, some time is useful for improve clarity.

e.g.type Celsius float64ortype IDnum int -

you can declare variables using the type alias

e.g.var temp Celsiusorvar pid IDnum

Variable initialization

- initialize in declaration

var x int = 100orvar x = 100- infer the type - initialize after declaration

var x intand thenx = 100 - uninitialized variables have a zero value

var x int // x = 0orvar x string // x = "" - Short variable declaration

x := 100

variable is declared as the type of expression on the right hand side

Can only do this inside a function.

Pointers

- Pointer is an address to data in memory

Two main operators that are associated with Pointers:

- & operator returns the address of a variable/function

- (*) operator returns data at an address (dereferencing) - If you put that in front of a Pointer to some address, put that in front of an address it will return you the data at that address.

e.g.

var x int = 1

var y inst

var ip *int // ip is pointer to int

ip = &x // ip noi points to x

y = *ip // y is now 1New

- Alternate way to create a variable

new()function creates a variable and return a pointer to the variable- Variable is initialized to zero

ptr := new(int)

*ptr = 3 // the value three is placed at the address specified by PTRVariable Scope

- The places in code where a variable can be accessed

var x = 4

func f() {

fmt.Printf("%d", x)

}

func g() {

fmt.Printf("%d", x)

}func f() {

var x = 4

fmt.Printf("%d", x)

}

func g() {

fmt.Printf("%d", x)

}Function g will have no reference to x.

Blocks

- A sequence of declarations and statements within matching brackets, {}

- Hierarchy of implicit blocks also

- Universe block - all go source

- Package block - all source in a package

- File block - all source in a file

- "if", "for", "switch" - all code inside the statement

- Clause in "switch" or "select" - individual clauses each get a block

There implicit blocks that you do not have to put explicit curly brackets for.

Lexical Scoping

- Go is a lexical scoped language using blocks

bi >= bjifbjis defined insidebi

Deallocating Memory

Once you declare a variable and your code is running your space needs to be allocated somewhere in memory for that variable, at some point that space has to be deallocated. When you're done using it all right.

- When a variable is no longer needed, it should be deallocated

- memory space is made available

- Otherwise, we will eventually run out of memory

func f() {

var x = 4

fmt.Printf("%d", x)

} Now say you call in your program you call this function f 100 times right, then it's going to allocate 100 different

spaces for this variable X right.

Stack vs Heap

- stack is dedicated to function call

- local variables are stored here

- deallocated after function completes (Go changes this a little bit)

- Heap is persistent

- Data on the heap must be deallocated when it is done being used

- in most compiled language (i.e. C) this is done manually

x = malloc(32)andfree(x) - Error prone, but fast

Garbage collector

- hard to determine when a variable is no longer use you do not want to deallocate a variable and later need that variable that you deallocated

func foo() *int {

x := 1

return &x

}

func main() {

var y = *int

y = foo()

fmt.Printf("%d", *y)

}This code is illegal in certain language, but it is legal in Go.

When the function ends that variable x should be deallocated, but in this case it's not the case because is returning a

pointer to x. Pointers make it difficult ot tell when deallocation is legal and when it is not.

- In interpreted languages this is done by the interpreter

- Java Virtual Machine

- Python Interpreter Once it determines that a variable is definitely not used, there no more pointers, no more references to that variable then the garbage collector deallocates it.

- Easy for the programmer (Deallocating memory is a big headache)

- Slow (need an interpreter)

- Go is a compiled language with enables garbage collection

- Implementation is fast

- Compiler determines stack vs heap it'll figure out this needs to go heap, this needs to go to the stack and it'll garbage collect appropriately.

- Garbage collection in the background It slows things down a little bit but it is a great advantage

Integers

- Generic int declaration

var x int - Different lengths and signs int8, int16, int32, int64, uint8, uint16, uint32, uint64 // can get larger you can control the integer size by specifying what size integer you want

- Binary operators Arithmetic: =, -, *, /, %, <<, >> Comparison: ==, !=, >, <, >=, <= Boolean: &&, ||

Type conversions

var x int32 = 1

var y int16 = 2

x = y // this instruction will fail, because x and y have different types

x = int32(y)Floating point

Real numbers

- float32 - ~6 digits of precision

- float64 - ~15 digits of precision

var x float64 = 123.45 // decimal

var y float64 = 1.2345e2 // scientific notation- complex numbers rapresented as two floats: real and imaginary

var x complex128 = complex(2, 3)String

ASCII and UNICODE

Each character has to be coded according to a standardized code.

- American Standard Code for Information Exchange

- Each character is associated with an (7) 8-bit number 'A' = 0x41 ASCII can represent 256 possible characters

- Unicode is a 32-bit character code

- UTF-8 is a sub set of Unicode. It can be 8-bit but it can go up to 32-bit. The first set of UTF-8 match ASCII

- Default in

gois UTF-8 - Code points - Unicode characters

- Rune - code point in

go

String are arbitrary sequence of bytes rapresented in UTF-8

- Sequence of arbitrary bytes

- Read-only, you cannot modify a string, you can create a new string that is a modified version of existing string

- often meant to be printed

- String literal - notable by double quotes

x := "Hi there"Each byte is a rune (UTF-8 code point)

The rune type is an alias for int32, and is used to emphasize than an integer represents a code point.

Unicode package

- Provides a set of functions to test categories of runes

isDigit(r rune)isSpace(r rune)isLetter(r rune)isLower(r rune)isPunct(r rune) - Perform conversions

toLower(r rune)toUpper(r rune)

Strings package

- Functions to manipulate UTF-8 encoded strings

- compare

- contains

- hasPrefix

- index

String manipulation

- Strings are immutable, but modified strings are returned

- replace

- toLower

- toUpper

- trimSpace

Strconv package

- conversion to and from string representations of basic data types

Atoi(s)convert string s to intItoa(s)FormatFloat(f, fmt, prec, bitSize)

Constants

- Expression whose values is known at compile time

- Type is inferred from righthand side

const x = 1.3

const (

y = 4

z = "Hi"

)iota

iotais a function to generate constants, it generates a set of related but distinct constants.- Often rapresents a property which has several distinct possible values

- e.g. days of the week

- e.g. months of the year

- Constants must be different but actual value is not important

- Like enumerated type in other languages

type Grades int

const (

A Grades = iota

B

C

D

F

)- Each constants is assigned to a unique integer

- Starts at 1 and increments

Control flow

Control Flow describes the order in which statements are executed inside a program.

Control Structures

Statements that alter control flow

if

if x > 5 {

fmt.Printf("Yup")

}for

iterates while a condition is true

for i := 10; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.Printf("Hi")

}switch

is a multi-way if statements

switch x {

case 1:

fmt.Printf("case1")

case 2:

fmt.Printf("case2")

default:

fmt.Printf("nocase")

}-

The

caseautomatically breaks at the end of the case -

Normal switches have a tag, but sometimes switch may not contain tag.

-

Case expression contains a boolean expression to evaluate

-

First true case is executed

switch {

case x > 1:

fmt.Printf("case1")

case x < -1

fmt.Printf("case 2")

default:

fmtp.Printf("nocase")

}break and continue

for i := 0; i < 10; i ++ {

if i == 5 { break }

fmt.Printf("Hi ")

}for i := 0; i < 10; i ++ {

if i == 5 { continue }

fmt.Printf("Hi ")

}scan

scanreads user input - it blocks the execution and waits until the user types in something and hits Enter- Takes a pointer as an argument

- Typed data is written to pointer

- Returns the number of scanned items

var appleNum int

fmt.Printf("Number of Apples: ")

num, err := fmt.Scan(&appleNum)

fmt.Printf(appleNum)Array

- fixed length series of elements of a chosen type

- element accessed using subscript notation

[,]<-- index in the middle of the square brackets - Indices start at 0

- Elements are initialized to zero value

var x [5]int

x[0] = 2

fmt.Printf(x[1])Array literal

- array pre-defined with values

var x [5]int = [5]{1, 2, 3, 4, 5} - lenght of literal must be the same of array

...for size in array literal infers size from number of initializersx := [...]int{1, 2, 3}

Iterating through arrays

- user for loop with the range keyword

x := [...]int {1, 2, 3}

for i, v := range x {

fmt.Prinf("ind %d, val %d", i, v)

}- range returns 2 values: index and element at index

Slice

- A "window" on an underlying array (a piece of it)

- Variable size up to the whole array

Every slice has three properties:

- Pointer: indicates the start of the slice

- Length: number of element in the slice

- Capacity: maximum number of elements

arr := [...]string{"a", "b", "c", "d", "e", "f", "g"}

s1 := [1:3]

s2 := [2:5] - We use colon inside the square bracket to define the beginning and the ends of the slide

- The second slice includes c, d, e but not f. The second number after the colon is just after the end.

- Slice can overlap and refer the same element inside the underlying array

Length and Capacity

- Two functions

len()andcap()

a1 := [3]int{1, 2, 3}

sli1 := [0:1]

fmt.Printf(len(sli1), cap(sli1))

// Result is "1 3"Accessing slices

- Writing to a slice changes the underlying array

- Overlapping slices refer the same array elements

arr := [...]string{"a", "b", "c", "d", "e", "f", "g"}

s1 := [1:3]

s2 := [2:5]

fmt.Printf(s1[1])

fmt.Printf(s2[0])

// These 2 statements print the same thingSlice Literals

- Can be used to initialize a slice

- Creates the underlying array and creates a slice to reference it

- Slice points to the start of the array, length is capacity

sli := []int{1, 2, 3}it is a slice because it does not have the array size or...keyword between the brackets

Make

- Create a slice (and array) using make

- 2-argument version: type and length/capacity

sli = make([]int, 10) - 3-argument version: type, length and capacity separately

sli = make([]int, 10, 15) - The third argument is the size of the array

Append

- Size of a slice can be increased by

append() - Adds elements to the end of the slice

- Insert into the underlying array, and it increases the size of the underlying array if necessary.

var sli = make (int[], 0, 3)

sli = append(sli, 100)Hash Table

- Contains key/value pairs - e.g. SSN/Email or GPS cord/address

- Each value is associated with a unique key

- Hash function is used to compute the slot for a key We can access things in constant time

Tradeoff of Hash Tables

Advantages

- Faster lookup than list Constant time vs linear-time

- Arbitrary keys no int like slice or array

Disadvantages

- May have collision Two keys hash to same slot

Maps

- Implementation of Hash Table

- Use

make()to create a Map

var idMap map[string]int

idMap = make(map[string]int)- May define a map literal

idMap := map[string]int{ "Joe": 3 }Accessing Map

- referencing a value with [key]

- Returns zero if key is not present

fmt.Printf(idMap["Joe"]) - Adding key/value pair into the map

idMap["jane"] = 42 - Delete key/value pair from the map

delete(idMap, "Joe")

Map functions

- Two-value assignment tests for existence of the key

id, p = idMap["Joe"]

pis true if the key is present in the map idis the value,pis presence of keylen()returns number of valuesfmt.Printf(len(idMap))

Iterating Through a Map

- Use for loop with

rangekeyboard - Two-value assignment with range

for key, value := range idMap {

fmt.Printf(key, val)

}Structs

- Aggregate data type

- Groups together other objects or arbitrary type Useful for organization purpose, it brings together variables that are

releated e.g. Person struct

- Name, Address, Phone

type Person struct {

name string

address string

phone string

}

var p1 Person- Each property is a field

p1contains values for fields

Accessing Structure fields

- Use dot notation

p1.name = "Joe"

x = p1.addressInitialize Structs

- Can use

new() - Initialize fields to zero (for

Personstructure this means that all fields are initialized with empty string)p1 := new(Person) - Can initialize using a struct literal

p1 := Person{name: "joe", address: "a st.", phone: "123"}

Protocol format

- RFC Request for comments

- Definitions of internet protocols and formats

- Example protocols:

- HTML (1866)

- URI (3986)

- HTTP (2616)

Protocol package

- Golang provides packages for important RFCs

- Function that encode and decode protocol format e.g. net/http - web communication protocol

http.Get(www.uci.edu)e.g. net TCP/IP and socket programmingnet.Dial("tcp", "uci.edu:80")

JSON

- JavaScript Object Notation

- RFC 7159

- Format to represent structured information

- Attribute-value pairs

- struct or map

- Basic value types

- Bool, number, string, array, "object"

JSON properties

- All unicode, all represented as unicode characters

- Human-readable

- Fairly compact representation

- Types can be combined recursively

JSON Marshalling

- Generating JSON representation from an object

type struct Person {

name string

addr string

phone string

}

p1 := Person(name: "Joe", addr: "a st.", phone: "123")

barr, err := json.Marshal(p1)Marshalreturns JSON rapresentation as[]byte

JSON Unmarshalling

var p2 Person

err := json.Unmarshal(barr, &p2)Unmarshalconverts a JSON[] byteinto a Go object- Object must "fit" JSON

[]byte

Files

- Linear access, not random access

- Mechanical delay

- Basic operations

- Open - get handle for access

- Read - read bytes into

[]byte - Write - write

[]byteinto file - Close - release handle

- Seek - move read/write head

ioutil File Read

- "io/util" package has basic functions

dat, e := ioutil.ReadFile("test.txt") datis[]bytefilled with contents of entire file- Explicit open/close are not necessary

- Large files cause a problem

ioutil File Write

dat := "Hello, World"

err := ioutil.WriteFile("outfile.txt", dat, 0777)- Writes

[]byteto file - Creates a file

- Unix-style permission bytes

OS package File Access

os.Open()opens a file- returns a file descriptor (File)

os.Close()closes a fileos.Read()reads from a file into a[]byte- fills the

[]byte - control the amount read

- fills the

os.Writewrites a[]byteinto a file

f, err := os.Open("dt.txt")

barr := make([]byte, 10)

nb, err := f.Read(barr)

f.Close- Reads and fills

barr Readreturns # of bytes read- May be less than

[]bytelength

f, err := os.Create("dt.txt")

bar := []byte{1, 2, 3}

nb, err := f.Write(barr)

nb, err := f.WriteString("Hi")Functions

main function is a special function you never call this function, when you run the program the main function is

invoked and rum immediately.

func PrintHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello, World")

}

func func main() {

PrintHello()

}e.g. parameters and arguments

func foo(x int, y int) {

fmt.Println(x*y)

}

func main() {

foo(2, 3)

}List arguments of same type

func foo(x, y int) { ... }Return values

func foo(x int) int {

return x + 1

}

y := foo(1)Multiple return values

func foo2(x int) (int, int) {

return x, x + 1

}

a, b := foo2(3)Call by value, reference

- Call by value

- passed arguments are copied to parameters

- Modifing parameters has no effect outside the function

func foo(y int) {

y = y + 1

}

func main() {

x := 2

foo(x)

fmt.Println(x)

}- Call by reference

- Programmer can pass a pointer as an argument

- Called function has direct access to caller variable in memory

func foo(y *int) {

*y = *y + 1

}

func main() {

x := 2

foo(&x)

fmt.Println(x)

}Passing arrays and slices

- Arrays arguments are copied

- Arrays can be big, and this can be a problem

func foo(x [3]int) int {

return x[0]

}

func main() {

a := [3]int{1, 2, 3}

fmt.Println(foo(a))

}- Possible to pass array pointers

func foo(x *[3]int) int {

(*x)[0] = (*x[0]) + 1

}

func main() {

a := [3]int{1, 2, 3}

foo(&a)

fmt.Println(a)

}- Messy and unnecessary

- Pass slices instead!

- Slices contain a pointer to the array

- Passing a slice copies the pointer

func foo(sli []int) []int {

sli[0] = sli[0] + 1

return sli

}

func main() {

a := []int{1, 2, 3}

foo(a)

fmt.Println(a)

}Functions

Function can be treated like other types

First-Class Values

- Variable can be declared with a function type

- Can be created dynamically

- Can be passed as arguments and returned as values

- Can be stored in a data structures

Variables as functions

var funcVar func (int) int

func incFn(x int) int {

return x+1

}

func main() {

funcVar = incFn

fmt.Println(funcVar(1))

}Functions as Arguments

func applyIt(afunct func (int) int, val int) int {

return afunct(int)

}

func incFn(x int) int { return x+1 }

func decFn(x int) int { return x-1 }

func main() {

fmt.Println(applyIt(incFn, 2))

fmt.Println(applyIt(decFn, 2))

}Anonymous Functions

Function without a name

func applyIt(afunct func (int) int, val int) int {

return afunct(val)

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(applyIt(func (x int) int { return x+1 }, 2))

}Returning functions

func MakeDistOrigin(o_x, o_y float64) func (float64, float64) float64 {

fn := func (x, y float64) float64 {

return math.Sqrt(math.Pow(x - o_x, 2) + math.Pow(y - o_y, 2))

}

return fn

}

func main() {

Dist1 := MakeDistOrigin(0, 0)

Dist2 := MakeDistOrigin(2, 2)

fmt.Println(Dist1(2, 2))

fmt.Println(Dist2(2, 2))

}Environment of a Function

- Set of all names that are valid inside a function

- Names defined locally, in the function

- Lexical scoping

- Environment includes names defined in the block where the function is defined

var x int

func foo(y int) {

x := 1

}Closure

- Function + its environment

- When functions are passed/returned, their environment comes with them!

Variable Argument Number

- Functions can take a variable number of arguments

- Use ellipsis ... to specify

- Treated as a slice inside the function

func getMax(vals ...int) int {

maxV := -1

for _, v := range vals {

if v > maxV {

maxV = v

}

}

return maxV

}Variadic Slice Arguments

func main() {

fmt.Println(getMax(1, 2, 3, 4, 5))

vslice := []{1, 3, 6, 4}

fmt.Println(getMax(vslice...))

}- Can pass a slice to a variadic function

- Needed the ... suffix

Deferred function calls

- Call can be deferred until the surrounding function complete

- Typically, used for cleanup activities

func func main() {

defer fmt.Println("bye!")

defer fmt.Println("Hello!")

}Deferred call arguments

- Arguments of a deferred call are evaluated immediately

func func main() {

i := 1

defer fmt.Println(i+1)

i++

defer fmt.Println("Hello")

}Object-Orientation in GO

Classes

- Collection of data fields and functions that share a well-defined responsibility

- Classes are a template

- Contains data fields, not data

Object

- Instance of a class

- Contains real data

Encapsulation

- Data can be protected from the programmer

- Data can be accessed only using methods

- Maybe we do not trust the programmer to keep data consistent

No "Class" keyword

- Most of OO languages have class keyword

- Data fields and methods are defined inside a class block

Associating methods with data

- Method has a receiver type that it is associate with

- Use dot notation to call the method

type MyInt int

func (mi MyInt) Double () int {

return int(mi*2)

}

func main() {

v := MyInt(3)

fmt.Println(v.Double())

}- Type must be defined in the same package as the method that you are associating with it

Implicit method argument

- Object of receiver type is an implicit argument to the function

- Call by Value

Structs, again

- Struct types compose data fields

type Point struct {

x float64

y float64

}- Traditional feature of classes

Structs with methods

- Structs and methods together allow arbitrary data and functions to be composed

func (p Point) DistToOrigin() {

t := math.Pow(p.x, 2) + math.Pow(p.y, 2)

return math.Sqrt(t)

}

func main() {

p1 := Point{x: 3, y: 4}

fmt.Println(p1.DistToOrigin())

}Controlling data access

- Can define public function to allow access to hidden data

package data

import "fmt"

var x int = 1

func PrintX() { fmt.Println(x) }package main

import "data"

func main() {

data.PrintX()

}- public functions inside the package have to start with a capital letter

Controlling access to Structs

- Hide fields of structs by starting field name with lower-case letter

- Defined public methods which access hidden data

package data

type Point struct {

x float64

y float64

}

func (p *Point) InitMe(xn, yn float64) {

p.x = xn

p.y = yn

}- Need

InitMe()to assign hidden data fields

func (p *Point) Scale(v float64) {

p.x = p.x * v

p.y = p.y * v

}

func (p *Point) PrintMe() {

fmt.Println(p.x, p.y)

}

func main() {

var p data.Point

p.InitMe(3, 4)

p.Scale(2)

p.PrintMe()

}- Access to hidden fields only through public methods

Limitation of methods

- Receiver is passed implicitly as an argument to the method

- Method cannot modify the data inside the receiver

- Example:

OffsetX()should increase x coordinate

func main() {

p1 := Point{3, 4}

p1.OffsetX(5)

}Large receiver

- If receiver is large, lots of copying is required

type Image [100][100]int

func main() {

i1 := GrabImage()

i1.BlurImage()

}- 10.000 ints copied to

BlurImage()

Pointer Receiver

func (p *Point) OffsetX(v float64) {

p.x = p.x + v

}- Receiver can be a pointer to a type

- Call by reference, pointer is passed to the method

- No need to dereference, Point is referenced as

pnot*p - Dereferencing is automatic with

.operator - Do not need to reference when calling the method e.g.

p.ScaleX(3)

Using Pointer Receivers

- Good programming practice:

- All methods for a type have pointer receivers, or

- All methods for a type have non-pointer receivers

- Mixing pointer/non-pointer receivers for a type will get confusing

- Pointer receiver allows modification

Polimorphism

- Ability for an object to have different "forms" depending on the context

- Example:

Area()function- Rectangle: area = base * height

- Triangle: area = 0.5 * base * height

- Identical at a high level of abstraction

- Different al a low level of abstraction

Go does not have inheritance

Interfaces

- Set of method signatures

- Implementation is NOT defined

- Used to express conceptual similarity between types

- Example: Shape2D interface

- All 2D shapes mush have

Area()andPerimeter()

Satisfying an Interface

- Type satisfies an interface if type defines all methods specified in the interface

- Same method signatures

- Rectangle and Triangle types satisfy the Shape2D interface

- Mush have

Area()andPerimeter()methods - Additional methods are ok

- Mush have

- Similar to inheritance with overriding

Defining an interface type

type Shape2D interface {

Area() float64

Perimeter() float64

}

type Triangle {...}

func (t Triangle) Area() float64 {...}

func (t Triangle) Perimeter() float64 {...}No need to state it explicity

Concrete vs Interface Types

Concrete types

- Specify the exact representation of the data and methods

- complete method implementation is included

Interface types

- Specifies some method signatures

- Implementations are abstracted

Interface value

- Can be treated like other values

- assigned to variables

- passed, returned

- Interface value has 2 components

- Dynamic type: Concrete type which is assigned to

- Dynamic value: Value of the dynamic type

- Interface value is actually a pair (dynamic type and dynamic value)

- An interface can have a nil dynamic value

var s1 Speaker

var d1 *Dog

s1 = d1- d1 has not concrete value yet

- s1 has a dynamic type but not dynamic value

- Nil dynamic value - can still call the

Speak()method of s1 - Does not need a dynamic value to call

- Need to check inside the method

func (d *Dog) Speak() {

if d == nil {

fmt.Println("")

} else {

fmt.Println(d.name)

}

}

var s1 Speaker

var d1 *Dog

s1 = d1

s1.Speak()Nil interface value

- interface with nil dynamic type

- very different from an interface with a nil dynamic value

- e.g.

var s1 Speakercannot call a method, runtime error

Empty interface

- Empty interfaces specifies no methods

- All types satisfy the empty interface

- Use it to have a function accept any type as parameter

func PrintMe(val interface{}) {

fmt.Println(val)

}Type assertions

Concealing type differences

- Interfaces hide the difference between types

- sometimes you need to treat different types in different ways

Exposing type differences

- Exmaple: Graphic program

DrawShape()will draw any shape- Underlying API has different drawing functions for each shape

DrawRect(r Rectangle) {...}DrawTriangle(t Triangle) {...}

- Concrete type of shape

smust be determined

Type assertions for disambiguation

- Type assertion can be used to determine and extract the underlying concrete type

func DrawShape(s Shape2D) bool {

rect, ok := s.(Rectangle)

if ok {

DrawRect(rect)

}

tri, ok := s.(Triangle)

if ok {

DrawTriangle(tri)

}

}- Type assertion extracts Rectangle from Shape2D (concrete type in parentheses)

- If interface contains concrete type

- rect == concrete, ok == true

- If interface does not contain concrete type

- rect == zero, ok == false

Type Switch

- Switch statement used with a type assertion

func DrawShape(s Shape2D) {

switch sh := s.(type) {

case Rectangle:

DrawRect(sh)

case Triangle:

DrawTriangle(sh)

}

}Error Handling

Error interface

- Many Go programs return error interface objects to indicate errors

type error interface {

Error() string

}- Correct operation: error == nil

- Incorrect operation:

Error()prints the error message

Concurrency

Big property of Go language is that concurrency is built into the language.

Compared to other languages like C and things or anything, Python, whatever, these languages you can do concurrent

programming in these languages, but it's not built into the language, which means, usually what you do is you import

some library.

Parallel Execution

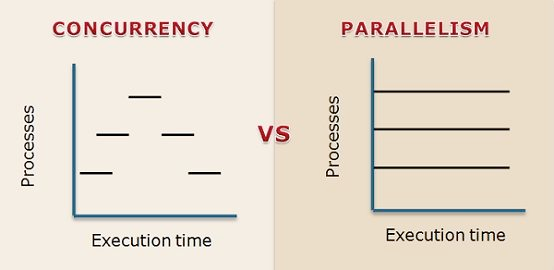

Concurrency and parallelism are two closely ideas.

- Two programs execute in parallel if they execute at exactly same time

- At time t, an instruction is being performed for both P1 and P2 Generally, one core runs one instruction at a time. So, if you want to have actual parallel execution, two things running at the same time, you need two processors or at least two processor cores.

- Need replicated hardware

Why use Parallel execution

- Tasks may complete more quickly (better throughput overall)

- Example: Two piles of dishes to wash. Two dishwasher can complete twice as fast as one

- Some tasks must be performed sequentially

- Example: Wash dish, dry dish

- Some tasks are parallelizable and some are not

Why use concurrency? Speedup without Parallelism

- Can we achieve speedup without Parallelism?

- Designer faster processors

- get speedup without changing software

- Design Processor with more memory

- Reduces the Von Neumann bottleneck

- cache access time = 1 clock cycle

- Main memory access time =~100 clock cycles

- Increasing on-chip cache improves performance

Moore's Law

- Predicted that transistor density would double every 2 years

- Smaller transistors switch faster

- Not a physical law, just an observation

- Exponential increase in density would lead to exponential increase in speed

Power / Temperature Problem

- Transistors consume power when they switch

- Increasing transistor density leads to increased power consumption

- Smaller transistors use less power, but density scaling is much faster

- High power leads to high temperature

- Air cooling (fans) can only remove so much heat

Dynamic Power

P = α * CFV^2- α is percent of time switching

- C is capacitance (related to transistor size)

- F is the clock frequency

- V is voltage swing (from lo to high)

- Voltage is important

- 0 to 5V uses much more power than 0 to 1.3V

Dennard Scaling

- Voltage should scale with transistor size

- Keeps power consumption, and temperature, low

- Problem: Voltage can't go too low

- Must stay above threshold voltage (transistors have what's called a threshold voltage. Below a certain voltage, they cannot switch on)

- Noise problems occur

- Problem: does not consider leakage power

- Dennard scaling must stop

Multi-Core systems

P = α * CFV^2- Cannot increase frequency

- Can still add processor cores, without increasing frequency

- Trend is apparent today

- Parallel execution is needed to exploit multi-core system

- Code made to execute on multiple cores

- Different programs on different core

Concurrent Execution

- Concurrent execution is not necessarily the same as parallel execution

- Concurrent: start and end times overlap

- Parallel: executed at exactly the same time

Concurrent vs Parallel

- Parallel tasks must be executed on different hardware

- Concurrent tasks may be executed on the same hardware

- Only one task actually executed at a time

- Mapping from tasks to hardware is not directly controlled by programmer

- At least not in go

Concurrent Programming

- Programmer determines which tasks can be executed in parallel

- Mapping tasks to hardware

- Operating system

- Go runtime scheduler

So you're doing concurrent programming but you've only got one core, so you can't actually get parallelism.

Hiding Latency

- Concurrency improves performance, even without parallelism

- Tasks must periodically wait for something

- i.e. wait for memory, network, screen etc..

- X = Y + Z read Y, Z from memory

- may wait 100+ clock cycles

- Other concurrent tasks con operate while one task is waiting

Parallel execution

Task 1 Task 2

| |

| |

| |

v v

Core 1 Core 2

Concurrent Execution

Task 1 Task 2

\ /

\ /

\ /

v v

Core 1

Hardware Mapping in go

- Programmer does not determine the hardware mapping

- Programmer makes parallelism possible

- Hardware mapping depends on many factors

- Where is the data?

- What are the communication costs?

Processes

- An instance of a running program

- things unique to a process

- Memory

- virtual address space

- Code, stack, heap, shared libraries

- Registers

- Program counter, data regs, stack pointer

Operating System

- Allows many processes to execute concurrently

- Process are switched quickly

- 20ms

- User has the impression of parallelism

- Operating system must give processes fair access to resources

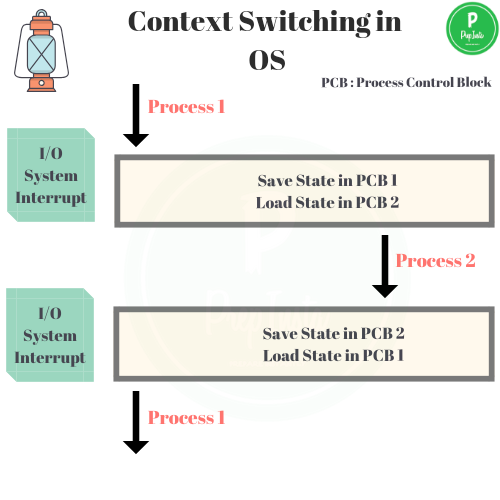

Scheduling Processes

- Operating system schedules processes for execution

- Gives the illusion of parallel execution

- There are many scheduling algorithm, the simplest is Round robin

- OS gives fair access to CPU, memory, etc..

Context Switch

Threads vs. Processes

- Context switch can be long, because it requires taking data, writing it to memory and then reading data from memory back into registers. So there is a lot of memory access and memory access can be slow.

- Thread share some context

- Many threads can exist in one process

- OS schedules threads rather than processes

Goroutines

- Like a thread in Go

- Many Goroutines execute within a single OS thread

Go Runtime Scheduler

- Schedules goroutines inside an OS thread

- Like a little OS inside a single OS thread. The OS schedules which thread runs at a time, then once the main thread is running, your Go program is runnining within main thread, the Runtime Scheduler can choose different Goroutine to execute at different times underneath that main thread.

- Logical processor (used by Runtime Scheduler) is mapped to a thread All these goroutines are running in one thread, no opportunity for parallelism, it's all concurrent. But, as programmer we can choose how many Logical processor we want, and we would do this according to how many cores we had.

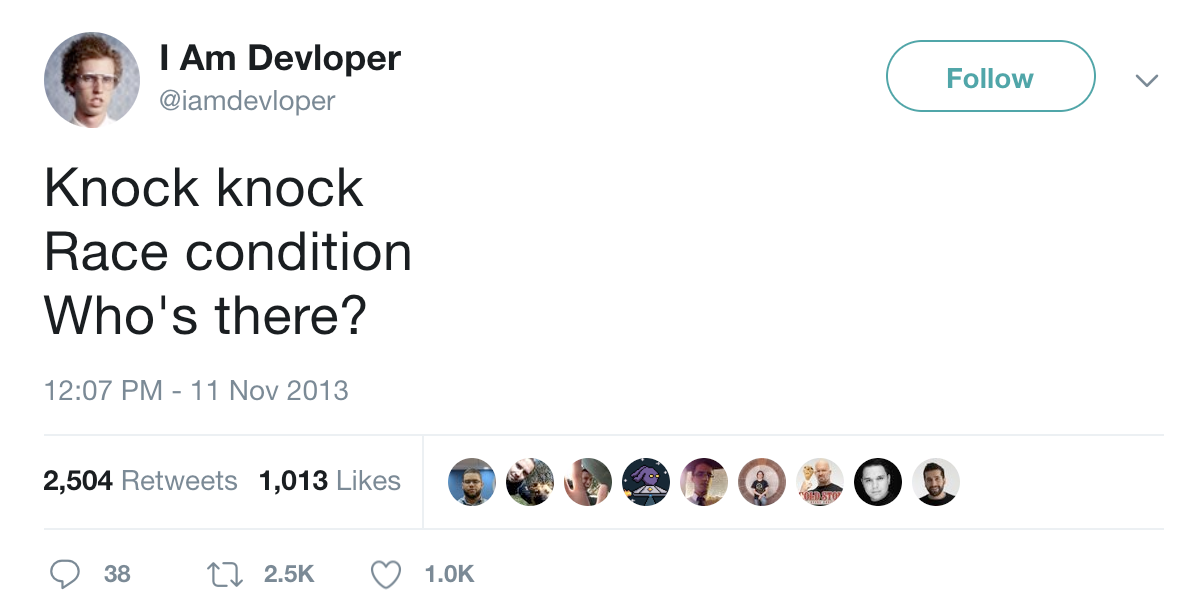

Interleavings

- Order of execution within a task is known

- Order of execution between concurrent tasks is unknown Means that two sets of instruction from two different task can be interleaved in different ways.

- Interleaving of instructions between tasks is unknown

- Many interleaving are possible

- Must consider all possibilities

- ordering is non-deterministic

Race conditions

- Outcome depends on non-deterministic ordering

- Races occurs due to communication

Communication between tasks

- Threads are largely independent but not completely independent

It is very common there is some level of sharing between threads, and the sharing of information is communication.

- Web Server, one thread per client

- Image processing, 1 thread per pixel block

Creating Go Routine

- One goroutine is created automatically to executre the

main() - Other goroutines are created using the

gokeyword

a = 1

go foo()

a = 2- New goroutine created for foo()

- Main goroutine does not block

Exiting a Goroutine

- A goroutine exits when its code is complete

- When the main goroutine is complete, all other goroutines exit

- A goroutine may not complete its execution because main completes early

Early Exit

func func main() {

go fmt.Printf("New routine")

fmt.Printf("Main routine")

}- Only "Main routine" is printed

- Main finished before the new goroutine started

Delayed Exit

func func main() {

go fmt.Printf("New routine")

time.Sleep(100*time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("Main routine")

}- add a delay in the main routine to give the new routine a chance to complete

- "New RoutineMain Routine" is now printed

Timing with Goroutines

- Adding a delay to wait for a goroutine is bad!

- Timing assumptions may be wrong

- Assumption: delay 100ms will ensure that goroutine has time to execute.

- Maybe the OS schedules another thread

- Maybe the Gor Runtime schedules another goroutine

- Timing is nondeterministic

- Need formal synchronization constructs

Synchronization

- Using global event whose execution is viewed by all threads, simultaneously

- In general synchronization is bad because it reduces your performance, but it is necessary.

Sync WaitGroups

- Sync package contains functions to synchronize between goroutines

sync.WaitGroupforces a goroutine to wait for other goroutines- Contains an internal counter

- increment counter for each goroutine to wait for

- Decrement counter when each goroutine completes

- Waiting goroutine cannot continue until counter is 0

Using WaitGroup

func foo(wg *sync.Waitgroup) {

fmt.Print("New routine")

wg.Done()

}

func main() {

var wgsync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(1)

go foo(&wg)

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("Main routine")

}Add()increments the counterDone()decrements the counterWait()blocks until the counter == 0

Goroutine Communication

- Goroutines usually work together to perform a bigger task

- Often need to send data to collaborate

- Example: find the product of 4 integers

- make 2 goroutines, each multiples a pair

- Main goroutine multiplies the 2 results

- Need to send ints from main routine to the two sub-routines

- Need to send results from sub-routines back to main routine

Channels

- Transfer data between goroutine

- Channels are typed

- Use

make()to create a channelc := make(chan int) - Send and receive data using the

<-operator - Send data on a channel

c <- 3 - Receive data from a channel

x := <- c

func prod(v1 int, v2 int, c chan int) {

c <- v1*v2

}

func func main() {

c := make(chan int)

go prod(1,2,c)

go prod(3,4,c)

a := <- c

b := <- c

fmt.Println(a*b)

}Unbuffered Channel

- Unbuffered channels cannot hold data in transit

- Default is unbuffered

- Sending blocks until data is received

- Receiving blocks until data is sent

e.g.

task1 task2

c <- 3

One hour later ...

x := <- c

Task one will sit there for an hour, until Task two reaches that read instruction

Blocking and Synchronization

- Channel communication is synchronous

- Blocking is the same as waiting for communication

- Receiving and ignoring the result is same as a

Wait()

Channel capacity

- Channel can contain a limited number of objects

- default size 0(unbuffered)

- capacity is the number of objects it can hold in transit

- Optional argument to

make()defines channel capacityc := make(chan int, 3) - Sending only blocks id buffer is full

- Receiving only block if buffer is empty

Use of Buffering

- Sender and receiver do not need to operate at exactly the same speed

- Speed mismatch is acceptable

- Average speeds must still match

Iterating through a Channel

- Common to iteratively read from a channel

for i := range c {

fmt.Println(i)

}- Continues to read from channel c

- One iteration each time a new value is received

iis assigned to the read value- iterates when sender calls

close(c)

Receiving from multiple Goroutines

- Multiple channels may be used to receive from multiple sources

- Data from both sources may be needed

- Read sequatianlly

a := <- c1

b := <- c2

fmt.Println(a*b)Select Statement

- May have a choice of which data to use

- i.e. First-come first-served

- Use the

selectstatement to wait on the first data from a set of channels

select {

case a = <- c1:

fmt.Println(a)

case b = <- c2:

fmt.Println(b)

}Select Send or Receive

- May select either send or receive operations

select {

case a = <- inchan:

fmt.Println("Received a")

case outchan <- b:

fmt.Println("Sent b")

}Select with an Abort Channel

- Use select with a separate abort channel

for {

select {

case a <- c

fmt.Println(a)

case <- abort:

return

}

}Default Select

- May want a default operation to avoid blocking

select {

case a = <- c1:

fmt.Println(a)

case b = <- c2:

fmt.Println(b)

default:

fmt.Println("nop")

}- When I have a default, you don't block, you just go and execute the default if none of the previous cases are ready.

Goroutines sharing variables

- Sharing variables concurrently can cause problems

- Two goroutines writing to a shared variable can interfere with each other

Concurrency-Safe

- Function can be invoked concurrently without interfering with other goroutines

e.g.

var i int = 0

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func inc() {

i++

wg.Done()

}

func main() {

wg.Add(2)

go inc()

go inc()

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println(i)

}- 2 goroutines write to

i ishould equal 2

Granularity of Concurrency

- Concurrency is at the machine code level

i = i + 1might be three machine instructions read i increment write i- Interleaving machine instructions causes unexpected problems

Correct sharing

- Don't let 2 goroutines write to a shared variable at the same time

- Need to restrict possible interleavings

- Access to share variables cannot be interleaved

Mutual Exclusion - Code segments in different goroutines which cannot execute concurrently

Sync.Mutex

- A Mutex ensures mutual exclusion

- Uses a binary semaphore

- Flag up - shared variable is in use

- Flag down - shared variable is available

Sync.Mutex Methods

Lock()method puts the flag up- shared variable in use

- If lock is already taken by a goroutine,

Lock()blocks until the flag is put down Unlock()method puts the flag down- Done using the shared variable

var i int = 0

var mut sync.Mutex

func inc() {

mut.Lock()

i = i+1

mut.Unlock()

}Synchronous Initialization

Initialization

-

must happen once

-

must happen before everything else

-

How do you perform initialization with multiple goroutines?

-

Could perform initialization before starting the goroutines

Sync.Once

- Has one method,

once.Do(f) - Function

fis called in multiple goroutines - All calls to

once.Do()block until the first returns- Ensures that initialization executes first

e.g.

- Make two goroutines, initialization only once

- Each goroutine executes

dostuff()

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func main() {

wg.Add(2)

go dostuff()

go dostuff()

wg.Wait()

}using Sync.Once

setup()should execute only once- "hello" should not print until

setup()returns

var on sync.Once

func setup() {

fmt.Println("Init")

}

func dostuff() {

on.Do(setup)

fmt.Println("Hello")

wg.Done()

}Execution result: Init/Hello/Hello

- Init appears only once

- Init appears before hello is printed

Synchronization Dependencies

- Synchronization causes the execution of different goroutines to depend on each other

G1 G2

ch <- 1 x := <- ch

mut.Unlock() mut.Lock()

- G2 cannot continue until G1 does something

Deadlock

- Circular dependencies cause all involved goroutines to block

- G1 waits for G2

- G2 waits fot G1

- Can be caused byu waiting on channels

e.g.

func dostuff(c1 chan int, c2 chan int) {

<- c1

c2 <- 1

wg.Done()

}

func main() {

ch1 := make(chan int)

ch2 := make(chan int)

wg.Add(2)

go dostuff(ch1, ch2)

go dostuff(ch2, ch1)

wg.Wait()

}dostuff()argument order is swapped- Each goroutine blocked on channel read

Deadlock detection

- Golang runtime automatically detects when all goroutines are deadlocked

- cannot detect when a subset of goroutines are deadlocked

Dining Philosophers Problem

- Classic problem involving concurrency and synchronization Problem

- 5 Philosophers sitting at a round table

- 1 chopstick is placed between each adjacent pair

- Want to eat rice from their plate, but needs two chopsticks

- Only one philosopher can hold a chopstick at a time

- Not enough chopsticks for everyone to eat at once

- Each chopstick is a mutex

- Each philosopher is associated with a goroutine and two chopsticks

type ChopS struct { sync.Mutex }

type Philo struct {

leftCS, rightCS *ChopS

}

func (p Philo) eat() {

for {

p.leftCS.Lock()

p.rightCS.Lock()

fmt.Println("eating")

p.rightCS.Unlock()

p.leftCS.Unlock()

}

}

func main() {

CSticks := make([]*Chops, 5)

for i := 0; i < 5; i ++ {

CSticks[i] = new(ChopS)

}

philos := make([]*Philo, 5)

for i := 0; i < 5; i ++ {

philos[i] = &Philo{CSticks[i], CSticks[(i+1)%5]}

}

for i := 0; i < 5; i ++ {

go philos[i].eat()

}

}Deadlock problem

- All Philosophers might lock their left chopstick concurrently

- All chopsticks would be locked

- No one can lock their right chopstick

Deadlock solution (Dykstra's way)

- Each philosopher picks up lowes numbered chopstick first

philos[i] = &Philo{CSticks[i], CSticks[(i+1)%5]}

- Philosopher 4 picks up chopstick 0 before chopstick 4

- Philosopher 4 blocks allowing philosopher 3 eat

- No deadlock, but philosopher 4 may starve (starvation problem)