DONE: Statistics, Tasks, TaskDetail, AddEditTask TODO: Clean ups

This version of the app is called TODO-MVI-RxJava. It is based on an Android ported version of the Model-View-Intent architecture and uses RxJava to implement this reactive architecture. It is initially a fork of the TODO-MVP-RXJAVA.

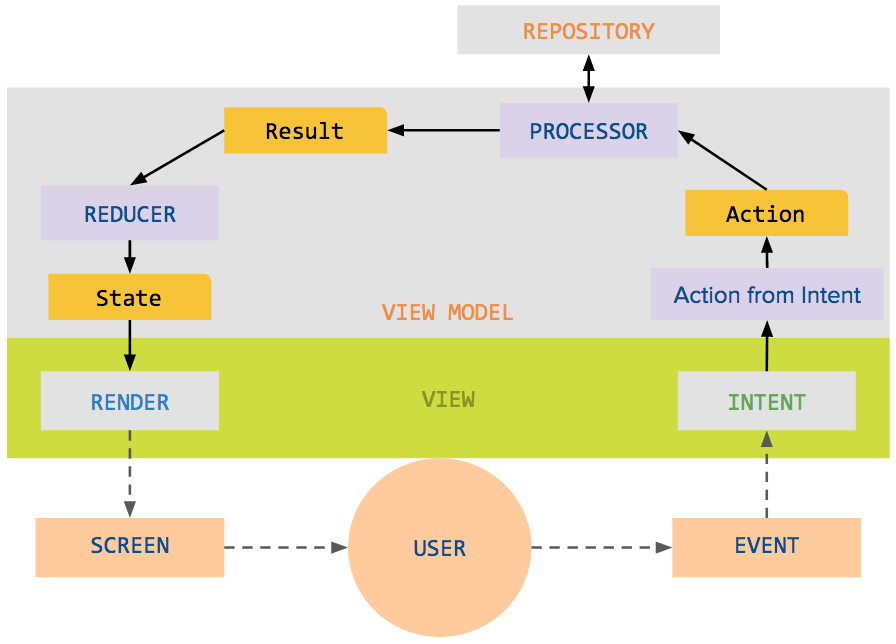

The MVI architecture embraces reactive and functional programming. The two main components of this architecture, View and ViewModel can be seen as functions, taking an input and emiting outputs. A View takes input from the ViewModel and emit back intents. A ViewModel takes input from the View and emit back states. This means the View has only one entry point to forward data to the ViewModel and vice-versa, the ViewModel only has one way to pass information to the View.

This is reflected in their API. For instance, A View only has two methods exposed:

public interface MviView {

Observable<MviIntent> intents();

void render(MviState state);

}A View will a) emit its intents to a ViewModel, and b) subscribes to this ViewModel in order to receive States needed to render its own UI.

A ViewModel only exposes two methods as well:

public interface MviViewModel {

void processIntents(Observable<MviIntent> intents);

Observable<MviState> states();

}A ViewModel will a) process the intents of the View, and b) emit a State back so the View can reflect the change, if any.

The MVI architecture sees the user as a function. The user receives a input―the screen from the application and ouputs back events (touch, click, scroll...). Including the User into the architecture map makes a lot of sense:

We saw what the View and the ViewModel were designed for, let's see what the other components are responsible of.

Intents represents, as their name goes, intents from the user, this goes from opening the view, clicking a button, or reaching the bottom of a scrollable list.

Intents are in this step translated into their respecting logic action. For instance, inside the Tasks module, the "opening the view" intent translates into "refresh the cache and load the data".

Actions are the logic to be executed by the Processor.

Processor simply executes the Action. Inside the ViewModel, this is the only place where side-effects should happen: data writing, data reading, etc.

Results are the result of what have been executed inside the Processor. Their can be errors, successful execution, or "currently running" result.

The reducer is responsible to generate the State which the View will use to render itself. The Reducer takes the latest State available, apply the latest Result to it and return a whole new State.

The State contains all the information the View needs to render itself.

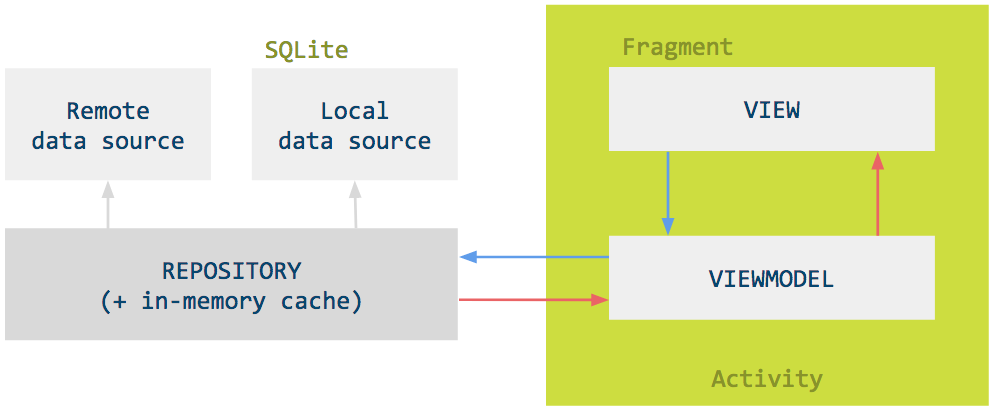

RxJava2 is used in this sample. Alike the TODO-MVP-RXJAVA sample, the data model layer exposes RxJava Observable streams as a way of retrieving tasks. In addition, when needed, writing methods exposes RxJava Completable streams to allow composition inside the ViewModel.

The TasksDataSource interface contains methods like:

Single<List<Task>> getTasks();

Single<Task> getTask(@NonNull String taskId);

Completable completeTask(@NonNull Task task);This is implemented in TasksLocalDataSource with the help of SqlBrite. The result of queries to the database being easily exposed as streams of data.

@Override

public Single<List<Task>> getTasks() {

...

return mDatabaseHelper.createQuery(TaskEntry.TABLE_NAME, sql)

.mapToList(mTaskMapperFunction)

.firstOrError();

}The TasksRepository combines the streams of data from the local and the remote data sources, exposing it to whoever needs it. In our project, the ViewModels and the unit tests are actually the consumers of these Observables.

Handling of the working threads is done with the help of RxJava's Schedulers. For example, the creation of the database together with all the database queries is happening on the IO thread. The subscribeOn and observeOn methods are used in the Presenter classes to define that the Observers will operate on the computation thread and that the observing is on the main thread.

Handling of the data immutability is done with the help of AutoValue. Our all value objects are interfaces of which AutoValue will generate the implementation.

Thread and data mutability is one easy way to shoot oneself in the foot. In this sample, pure functions are used as much as possible. Once an Intent is emited by the View, up until the ViewModel actually access the repository, 1) all objects are immutable, and 2) all methods are side-effect free. Same goes on the way back, from the creation of a repository Result, to the state reduced from this Result and the last State, until the View renders it.

The ViewModel should outlive the View on configuration change. To do so, we use the Architecture Components library to instantiate our ViewModel.

Logging is handled by Timber (Used here because ViewModel's tests are run on the JVM and not Android). By logging every event that goes through the ViewModel's unidirectional data flow, it becomes really easy to see what the User is actually doing and what the View will render too. Since the State contains everything the View needs to render itself, simply by looking at the logs, one could recreate the same View the User was seeing at any moment. This is specially helpful when chasing bug.

For instance:

Intent: RefreshIntent{forceUpdate=false}

Result: LoadTasks{status=IN_FLIGHT, tasks=null, filterType=null, error=null}

State: TasksViewState{isLoading=true, tasksFilterType=ALL_TASKS, tasks=[], error=null, taskComplete=false, taskActivated=false, completedTasksCleared=false}

Result: LoadTasks{status=SUCCESS, tasks=[Task with title title], filterType=null, error=null}

State: TasksViewState{isLoading=false, tasksFilterType=ALL_TASKS, tasks=[Task with title title], error=null, taskComplete=false, taskActivated=false, completedTasksCleared=false}

Intent: CompleteTaskIntent{task=Task with title title}

Result: CompleteTaskResult{status=IN_FLIGHT, tasks=null, error=null}

State: TasksViewState{isLoading=false, tasksFilterType=ALL_TASKS, tasks=[Task with title title], error=null, taskComplete=true, taskActivated=false, completedTasksCleared=false}

Result: CompleteTaskResult{status=SUCCESS, tasks=[Task with title title], error=null}

State: TasksViewState{isLoading=false, tasksFilterType=ALL_TASKS, tasks=[Task with title title], error=null, taskComplete=false, taskActivated=false, completedTasksCleared=false}

Building an app following the MVI architecture is not trivial as it uses new concepts from reactive and functional programming.

Developers need to be familiar with the observable pattern and functional programming.

Very High. The ViewModel is totally decoupled from the View and so can be tested right on the jvm. Also, given that the RxJava Observables are highly unit testable, unit tests are easy to implement.

Similar with TODO-MVP. There is actually no addition, nor change compared to the TODO-MVP sample. There is only some deletion of obsolete methods that were used by the ViewModel to communicate with the View.

Compared to TODO-MVP, new classes were added for 1) setting the interfaces to help writing the MVI architecture and its components, 2) providing the ViewModel instances via the ViewModelFactory, and 3) handing the Schedulers that provide the working threads.

TODO

High.

Medium as reactive and functional programming, as well as Observables are not trivial.