Copyright (C) 2021 Marc Battyani

You can redistribute this document and/or modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foundation, either version 3 of the License, or (at your option) any later version.

This document is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the GNU General Public License for more details.

This is a personal blog post and the opinions expressed here are only my own.

People familiar with FPGA market data feed handlers can skip Part I and go directly to the more technical Part II

There has been a lot of discussions about high frequency trading but so far there has been almost no public information and even less open source code on how FPGA market data feed handlers works and what performance they can achieve.

The first 100% pure FPGA market data feed handler was invented in 2008 by myself at NovaSparks, the company I created that same year to commercialize it.

It was for the EUREX stock exchange with a record low latency for the time of 1.4 microseconds. Since then the market data feeds have increased from 1 to 10+ Gbit/s and the latencies have decreased to a few 100’s of nanoseconds.

To fill that void, I’ve decided to share this document and associated code for a fully working sub 25 nanoseconds Open Source NASDAQ ITCH FPGA Parser.

- The exchange (NASDAQ here)

- Manages the order books, execute the trades, etc.

- Encodes any changes in orders, trades, stock status, etc. into ITCH protocol messages

- These messages are then aggregated into packets

- Those packets are sent into a 10Gbit/s Ethernet connections with the IP multicast protocol

- The market data processing FPGA is directly connected to the 10Gb/s Ethernet

- A standard Ethernet core transforms the Ethernet data into an AXI stream of 32 bits words at 322.27MHz

- This NASDAQ ITCH parser inside that FPGA

- Takes that AXI stream of Ethernet data

- Decodes the Ethernet and IP Multicast headers and filters out unrelated Ethernet packets

- Parses and extract all the ITCH messages needed for ultra low latency trading (orders, trades, various events and actions)

- Skips some information messages which are not useful for trading

- Aggregates the message data into 297 bit wide commands

- Transmits these commands in 1 clock cycle to the next FPGA cores as a AXI stream

- All that is fully pipelined and takes 8 clock cycles that is 24.8 nanoseconds

In FPGA designs there are 2 important parameters: Bandwidth and pipeline latency

The bandwidth is easy; it’s how much data we get per second. Here we get that data from a 10Gbit/s Ethernet connection which is 1.25 GBytes/s. For instance a 125 bytes packet (1000 bits) is transmitted in 100 nanoseconds.

Latency is how long it takes for the command to be output from the time the data has arrived. The reason why it’s a little bit more tricky is that as we are decoding the data from the 10Gbit/s Ethernet connection as soon as we get those bytes and we don’t even wait for the end of the packet. Thus we can’t measure the latency from the time the packet has arrived because we have already decoded and output the commands on the fly while the packet bytes were arriving.

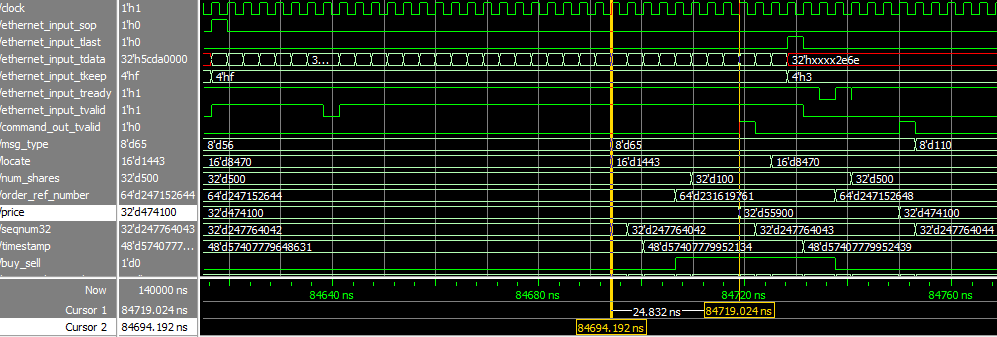

Here we measure the latency from the arrival of the last byte of a message to the output of the decoded command and it is 8 clock cycles at 322MHz which is 24.8 nanoseconds. Indeed that design is fully pipelined that means that it will input 4 bytes of data at each clock cycle and always deliver the decoded command exactly 8 clock cycles later.

As an illustration of how fast that 24.8ns is, the light can only travel by around 7.45 meters (24.44 ft) in that time. In an optical fiber cable the speed of light is around 30% slower and 24.8ns is equivalent to 5 meters (16.4 ft) of cable.

On that simulation the first cursor is where the price arrives in the incoming ethernet packet and the second cursor (24.8ns later) is when that price is fully decoded and output to the next core.

On that simulation the first cursor is where the price arrives in the incoming ethernet packet and the second cursor (24.8ns later) is when that price is fully decoded and output to the next core.

Once the messages have been decoded into commands the next stages can vary a lot depending on the application. The commands can be used to build the order book, to compute various indicators or indexes and to trigger actions. That second stage typically has a latency of a few 10’s of ns too.

The last stage would be to send orders to the exchanges. The latency of that stage depends on the exchange protocols, the checks and controls, etc.

The full trading loop can be as fast as a few 100’s of nanoseconds

Programming FPGAs is hard and complex. Typical code for FPGA is mostly written in languages with a very low level of abstraction like VHDL and verilog which work at the wire, signal and clock level. Here is a typical example of verilog:

wire reset;

wire clock;

reg [31:0] fpga_time;

always @(posedge clock)

begin

if (reset)

fpga_time <= 0;

else

fpga_time <= fpga_time + 1;

end;Writing parsers, hash tables and data processing core with those languages is time consuming and error prone. When I wrote the first full FPGA feed handler in 2008 I started to write the decoding of a few messages in VHDL but soon realized it would be much better to have a compiler specialized for that kind of FPGA applications.

The idea is to have a compiler that can directly take a description of the messages and automatically generates the verilog or VHDL needed to decode them.

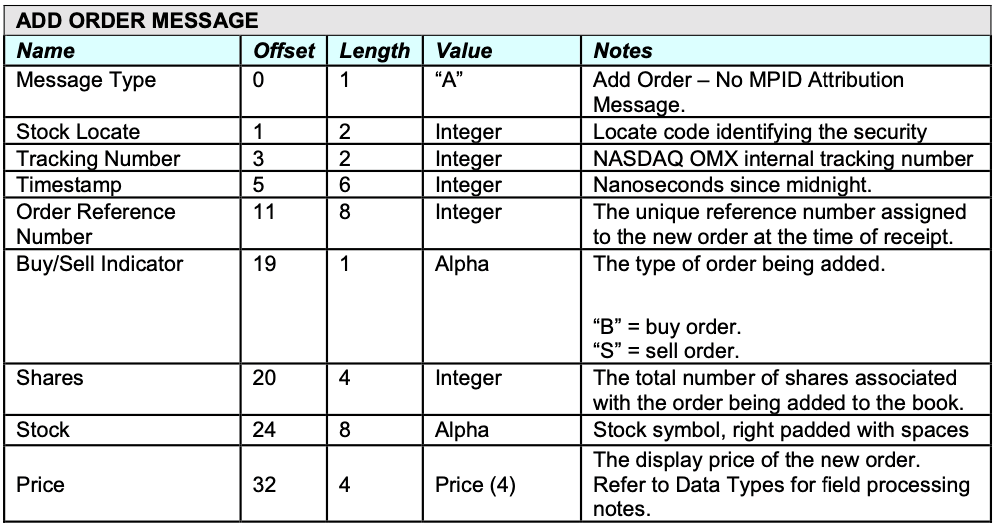

For instance this is the “add order” message as given in the NASDAQ ITCH 5.0 specification:

And here is the description of that “add order” message for the compiler:

(65, add_order, # A

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

order_ref_number::uint64,

buy_sell::uint8,

num_shares::uint32,

Symbol::uint64,

price::uint32),That parser is written using the 4th generation of Fractal’s Hardware Compiler which is a new compiler platform built from scratch since 2014. It is written in Common Lisp but can take inputs in the Julia syntax in addition to the Lisp one.

The code commented below is in the Julia syntax but both versions are on GitHub.

First we declare an hardware module named nasdaq_itch_parser that takes an input data stream named ethernet_input and an output stream named command_out. That core will work at 322.265 MHz

hw_module(nasdaq_itch_parser, "Extraction and parsing of Nasdaq ITCH 5.0 orders and trade related messages",

stream_in = ethernet_input, stream_out = command_out, frequency = 322.265625e6);The Ethernet AXI input stream interface definition

@input::uint32 ethernet_input_tdata;

@input::uint4 ethernet_input_tkeep;

@input::bit ethernet_input_tlast ethernet_input_tvalid;

@output::bit ethernet_input_tready::special_use;The commands AXI output stream interface definition

@input command_out_tready::bit;

@output command_out_tdata::uint297;

@output command_out_tvalid::bit;Let’s register the inputs to have a clean input. Note that we only register one signal of the interface but the compiler will automatically register them all

ethernet_input_tlast = register(ethernet_input_tlast);Adding an extra clock cycle after the last word of each packet to be able to output the last command of a packet

change_execution((after_packet, :exec_when, ethernet_input_tlast));Let’s find the start of a packet

start_of_packet::bit = falling_edge(after_packet, initial_value = 1);The memory mapped registers interface is used to give some parameters like the IP address and port of the NASDAQ Ethernet data feed.

def_mmap_interface(config_registers, "The config/status registers", data_width = 32, nb_words = 8);

@with_var_options (interface = config_registers) begin

@input::uint32 nasdaq_ip_addr::(:untimed, "The IP address of the incoming NASDAQ feed.", :initial_value = 0xE9360C65);

@input::uint16 nasdaq_udp_port::(:untimed, "The IP port of the incoming NASDAQ feed.", :initial_value = 26400);

end;Then we can use the def_message_parser2 macro to define the Ethernet and IP headers followed by the ITCH messages

def_message_parser2(parser, sop = start_of_packet,

data_valid = ~after_packet & ethernet_input_tvalid,

tkeep = ethernet_input_tkeep, data_in = ethernet_input_tdata,

protocol_desc =

(

# Ethernet header

dst_mac::uint48,

src_mac::uint48,

eth_type::uint16,

# IP header

version_and_IHL::uint8,

DSCP_ECN::uint8,

total_length::uint16,

time_to_live::uint8,

protocol::uint8,

header_checksum::uint16,

ip_src_addr::uint32,

ip_dest_addr::uint32,

# UDP header

udp_src_port::uint16,

udp_dest_port::uint16,

udp_len::uint16,

udp_checksum::uint16,

# MOLD header

mold_session::uint64,

mold_session_msb::uint16,

seqnum::uint64,

msg_count::uint16,

# ITCH 5.0 Messages

(:loop, (msg_length::uint16, :nil),

msg_type::uint8,

(:case, (msg_type),

(83, system_event_message, # S

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

event_code::uint8),

(72, stock_trading_action, # H

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

symbol::uint64,

trading_state::uint8),

(89, reg_sho, # Y

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

symbol::uint64,

reg_sho_action::uint8),

(65, add_order, # A

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

order_ref_number::uint64,

buy_sell::uint8,

num_shares::uint32,

symbol::uint64,

price::uint32),

(70, add_order_with_mpid, # F

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

order_ref_number::uint64,

buy_sell::uint8,

num_shares::uint32,

symbol::uint64,

price::uint32,

attribution::uint32),

(85, order_replace, # U

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

prev_order_ref_number::uint64,

order_ref_number::uint64,

num_shares::uint32,

price::uint32),

(69, order_executed, # E

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

order_ref_number::uint64,

num_shares::uint32,

match_number::uint64),

(67, order_executed_with_price, # C

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

order_ref_number::uint64,

num_shares::uint32,

match_number::uint64,

printable::uint8,

price::uint32),

(88, order_cancel, # X

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

order_ref_number::uint64,

num_shares::uint32),

(68, order_delete, # D

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

order_ref_number::uint64),

(80, trade, # P

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

order_ref_number::uint64,

buy_sell::uint8,

num_shares::uint32,

symbol::uint64,

price::uint32,

match_number::uint64),

(81, cross_trade, # Q

locate::uint16,

tracking::uint16,

timestamp::uint48,

num_shares_msb::uint32,

num_shares::uint32,

price::uint32,

match_number::uint64,

cross_type::uint8)))));

That’s all there is to do to decode the Ethernet packet and the messages!

Computes the global exchange seqnum for each message with a counter

def_counter(seqnum32::32, increment = msg_type_sync, enable = ethernet_input_tvalid, clear = delay(seqnum_sync, 3), reset_value = seqnum);Only accepts the packets which have the correct IP address and port

packet_ok::bit = (ip_dest_addr == nasdaq_ip_addr) & (udp_dest_port == nasdaq_udp_port);Stores various event codes into num_shares to reduce the AXI stream width

num_shares = case_expr(msg_type, ((83, event_code), (72, trading_state), (89, reg_sho_action), (:default, num_shares)))Bundles the output into the command_out AXI4 stream data

command_out_tdata = register(concat(msg_type, order_ref_number, prev_order_ref_number, locate, buy_sell == 66, price, num_shares, seqnum32, timestamp));And finally the last step is to compute when the command out is valid

command_out_tvalid = packet_ok & (price_sync | event_code_sync | trading_state_sync | reg_sho_action_sync | ((msg_type == 69) | (msg_type == 88)) & num_shares_sync);Done! From that the Fractal Compiler will generate a verilog core that can be used in the final FPGA design.

Hopefully this post has been helpful to explain how fast the ultra-low latency pure FPGA based trading systems are.

The number to remember here is that at less than 25 nanoseconds it’s as fast as a 5 meters (16 ft) of cable so keep cabling short.

At that time the compiler is not publicly available but we use it daily at Fractal Scientific to make FPGA designs for our customers as well as our own sensor designs.

More information at Fractal Scientific