Written by Irmen de Jong (irmen@razorvine.net)

This is a structured programming language for the 8-bit 6502/6510/65c02 microprocessor from the late 1970's and 1980's as used in many home computers from that era. It is a medium to low level programming language, which aims to provide many conveniences over raw assembly code (even when using a macro assembler).

Full documentation (syntax reference, how to use the language and the compiler, etc.) can be found at: https://prog8.readthedocs.io/

GNU GPL 3.0, see file LICENSE

- prog8 (the compiler + libraries) is licensed under GNU GPL 3.0

- exception: the resulting files created by running the compiler are free to use in whatever way desired.

- reduction of source code length over raw assembly

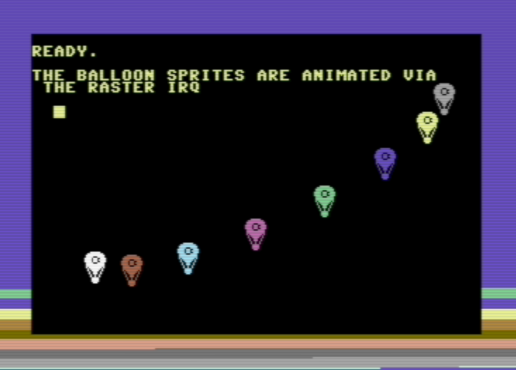

- fast execution speed due to compilation to native assembly code. It's possible to write certain raster interrupt 'demoscene' effects purely in Prog8.

- modularity, symbol scoping, subroutines

- various data types other than just bytes (16-bit words, floats, strings)

- floating point math is supported if the target system provides floating point library routines (C64 and Cx16 both do)

- strings can contain escaped characters but also many symbols directly if they have a petscii equivalent, such as "♠♥♣♦π▚●○╳". Characters like ^, _, , {, } and | are also accepted and converted to the closest petscii equivalents.

- automatic static variable allocations, automatic string and array variables and string sharing

- subroutines with input parameters and result values

- high-level program optimizations

- small program boilerplate/compilersupport overhead

- programs can be run multiple times without reloading because of automatic variable (re)initializations.

- conditional branches

- 'when' statement to provide a concise jump table alternative to if/elseif chains

- many built-in functions such as

sin,cos,rnd,abs,min,max,sqrt,msb,rol,ror,swap,sortandreverse - various powerful built-in libraries to do I/O, number conversions, graphics and more

- convenience abstractions for low level aspects such as ZeroPage handling, program startup, explicit memory addresses

- inline assembly allows you to have full control when every cycle or byte matters

- supports the sixteen 'virtual' 16-bit registers R0 - R15 from the Commander X16, and provides them also on the C64.

- encode strings and characters into petscii or screencodes as desired (C64/Cx16)

Rapid edit-compile-run-debug cycle:

- use a modern PC to do the work on, use nice editors and enjoy quick compilation times

- can automatically run the program in the Vice emulator after succesful compilation

- breakpoints, that let the Vice emulator drop into the monitor if execution hits them

- source code labels automatically loaded in Vice emulator so it can show them in disassembly

Two supported compiler targets (contributions to improve these or to add support for other machines are welcome!):

- "c64": Commodore-64 (6510 CPU = almost a 6502)

- "cx16": CommanderX16 (65c02 CPU)

- If you only use standard kernal and prog8 library routines, it is possible to compile the exact same program for both machines (just change the compiler target flag)!

64tass - cross assembler. Install this on your shell path. A recent .exe version of this tool for Windows can be obtained from my clone of this project. For other platforms it is very easy to compile it yourself (make ; make install).

A Java runtime (jre or jdk), version 11 or newer is required to run a prepackaged version of the compiler. If you want to build it from source, you'll need a Java SDK + Kotlin 1.3.x SDK (or for instance, IntelliJ IDEA with the Kotlin plugin).

It's handy to have an emulator (or a real machine perhaps!) to run the programs on. The compiler assumes the presence of the Vice emulator for the C64 target, and the x16emu emulator for the CommanderX16 target.

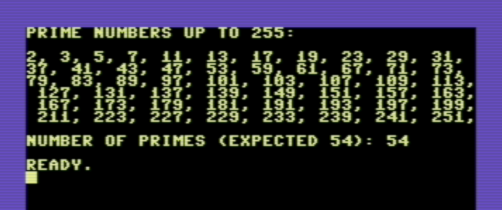

This code calculates prime numbers using the Sieve of Eratosthenes algorithm::

%import textio

%zeropage basicsafe

main {

ubyte[256] sieve

ubyte candidate_prime = 2 ; is increased in the loop

sub start() {

sys.memset(sieve, 256, false) ; clear the sieve

txt.print("prime numbers up to 255:\n\n")

ubyte amount=0

repeat {

ubyte prime = find_next_prime()

if prime==0

break

txt.print_ub(prime)

txt.print(", ")

amount++

}

txt.nl()

txt.print("number of primes (expected 54): ")

txt.print_ub(amount)

txt.nl()

}

sub find_next_prime() -> ubyte {

while sieve[candidate_prime] {

candidate_prime++

if candidate_prime==0

return 0 ; we wrapped; no more primes

}

; found next one, mark the multiples and return it.

sieve[candidate_prime] = true

uword multiple = candidate_prime

while multiple < len(sieve) {

sieve[lsb(multiple)] = true

multiple += candidate_prime

}

return candidate_prime

}

}

when compiled an ran on a C-64 you'll get:

One of the included examples (wizzine.p8) animates a bunch of sprite balloons and looks like this:

Another example (cube3d-sprites.p8) draws the vertices of a rotating 3d cube:

If you want to play a video game, a fully working Tetris clone is included in the examples:

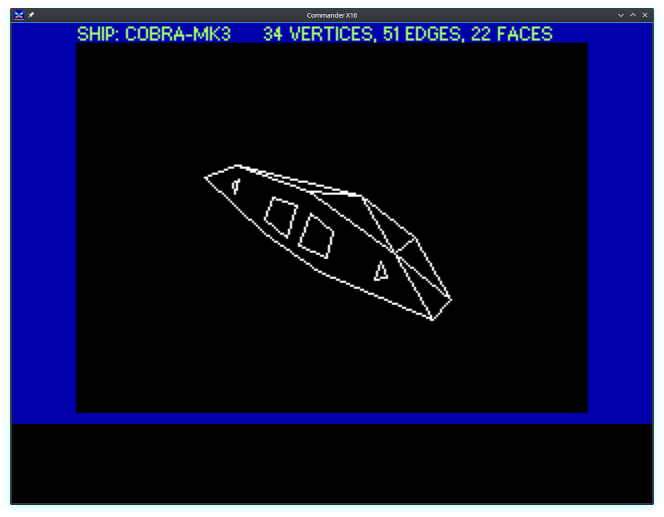

There are a couple of examples specially made for the CommanderX16 compiler target. For instance here's a well known space ship animated in 3D with hidden line removal, in the CommanderX16 emulator: