An implementation of the adaptation procedure on misinformation games, in Python 3. For the details regarding the theory and algorithm behind this implementation, see the included paper (see ./documentation/SETN_final_named.pdf). We strongly recommend to read the paper first.

In this second version of the program, we added the following features (see related sections bellow):

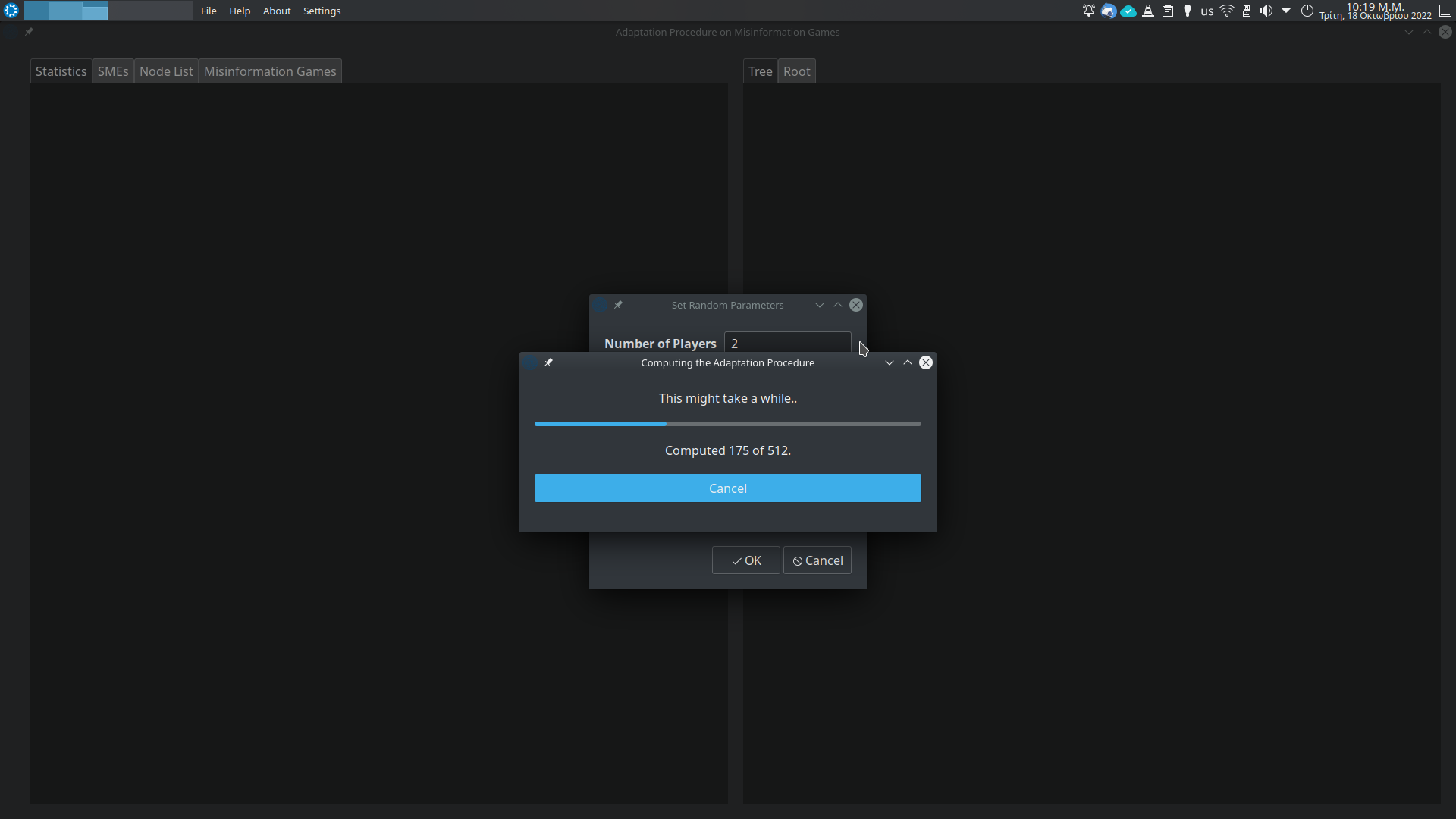

- Parallelism via Multithreading.

- Various Approximation Methods, for reducing the Rounding Error.

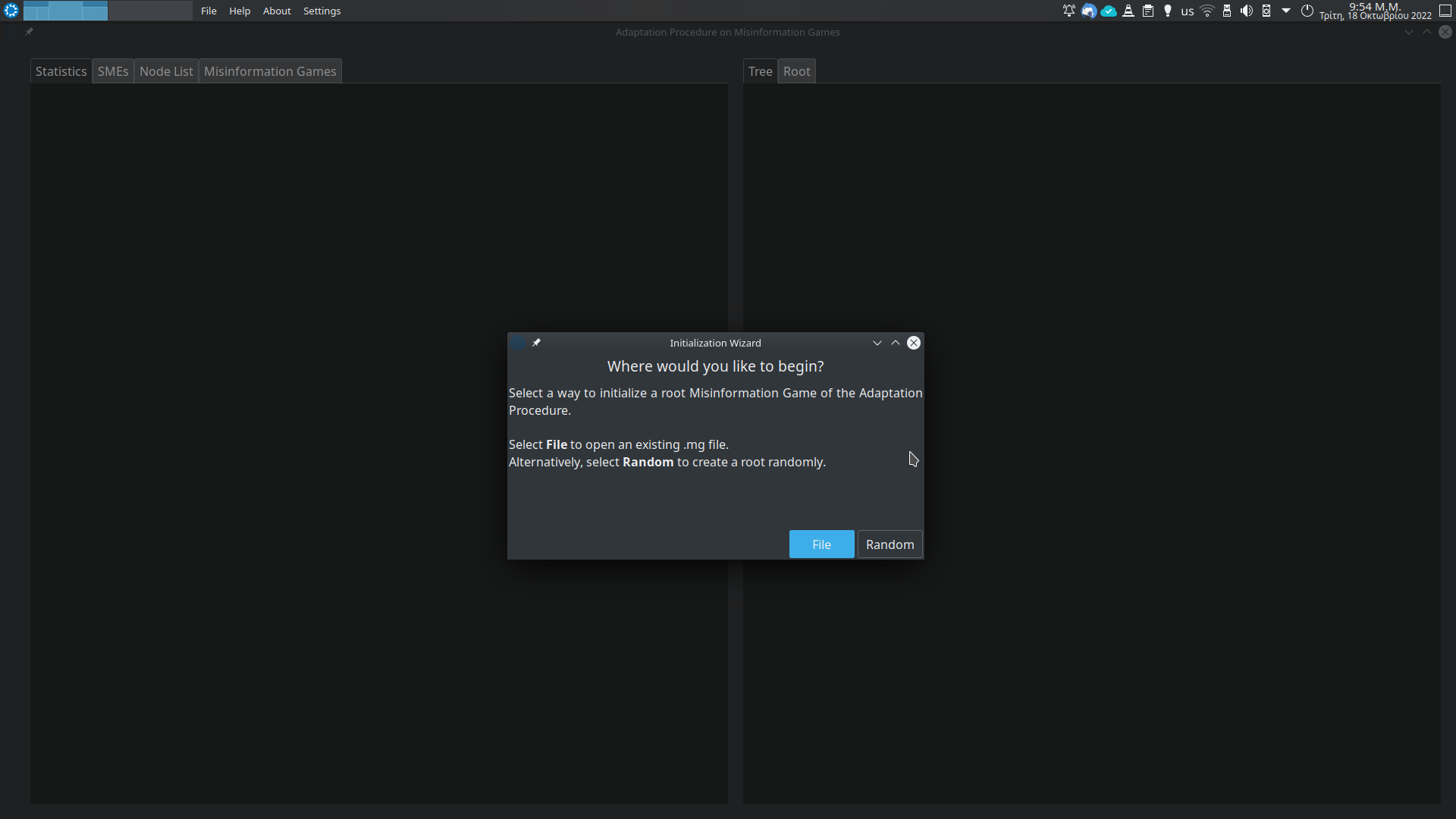

- A Graphical User Interface

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The installation process takes three steps. The first is installing the Python3 Programming Language and the related packages. The second step regards the installation of the two subsystems used by the python code (as subprocesses), the CLINGO language and the GAMBIT package. The third step is installing the necessary third party python libraries. The installation instructions where written for the Ubuntu 22.04 OS, but should be similar for any Linux distribution. The Windows OS is currently unsupported. The installation on windows should follow the similar steps, but some extra configuration may be needed. Also, for the program to run on Windows some (minor) changes in the program's code may be necessary, e.g. changing the directory separator from / to \.

Here we give the instructions of installing the latest Python 3 release and the Package Installer for Python (PIP). Naturally a Python interpreter is necessary for the execution of the program's code. On the other hand, PIP allows the easy installation of the necessary third party libraries. The installation of Jupyter Notebook, is optional, since the program can be executed without it. We use Jupyter only for presentation purposes, in order to run the ./source/2x2_exam.ipynb file. This file contains an elegant and user-friendly presentation of the program's execution on a simple 2x2 misinformation game.

The Python 3 language comes pre-installed in Ubuntu 22.04. Nevertheless, if for some reason isn't available on your system you can install it with,

sudo apt install python3

Note: Currently the version 3.8.10 is the latest stable release of Python 3, available in the Ubuntu repository. Note that the latest version available in Ubuntu repository falls a bit behind the latest version released for Windows. This should not pose a problem.

You can install the Package Installer for Python (PIP) with the following command.

sudo apt install python3-pip

You can install the Jupyter Notebook with the following comand

sudo apt install jupyter-notebook

For convenience we use the command python instead of the python3. You can create an alias for the python3 command, with

alias python=python3

Otherwise, use the python3 command instead of python, in the listings bellow.

There are two subsystems that our program utilises, the CLINGO Answer Set Programming Language and the GAMBIT package for computations on Normal Form Games.

Firstly, we give the instructions to install the CLINGO language for Answer Set Programming. You can install CLINGO in Ubuntu with the following command,

sudo apt install gringo

After a successful installation the command clingo should be available on your command line prompt.

The installation of the GAMBIT is a bit more elaborate than CLINGO, since it's not available on Ubuntu repository. The latest version of GAMBIT for linux is available here. We will use GAMBIT 16 here. GAMBIT 15 isn't supported in modern systems, as many of the C++ commands it uses are now deprecated. Please install the suggested version. The GAMBIT is released for Linux as a simple .tar.gz file. After downloading the compressed file, extract it, either by the desktop environment (recommended), or using the command,

tar –xvzf gambit-16.0.2.tar.gzLet ./gambit-16.0.2 be the directory the above compressed file is extracted. cd to this directory. The installation follows three simple steps, i.e. ./configure, make, sudo make install. If the compiling tools make and g++ aren't available on your system you can install them by typing, sudo apt install make and sudo apt install g++ respectively. After, installing the necessary tool, you can proceed with the installation, typing sequentially.

$ ./configure

$ make

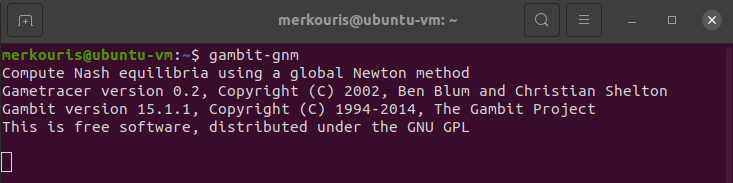

$ sudo make installThe make command will throw a few warnings. This will not be a problem if no errors are thrown. If the sudo make install command is executed successfully, then the installation should be completed. If the installation is successful, then the command gambit-gnm should be available. Open any directory on terminal and type the command gambit-gnm. You should get the following:

Type Ctrl+D or Ctrl+C to exit the prompt. The gambit-gnm is the only GAMBIT command used by our application.

Notes: If the make command is completed successfully the GAMBIT commands are accessible locally, by providing a path to the GAMBIT's directory. With sudo make install the commands are made available globally. If something goes wrong with the make command, use make clean and retry.

Now we will install the following third party python libraries that are used from our application. We install all the libraries using pip.

termcolora library that prints colourful text on terminal.- Install with

pip install termcolor.

- Install with

anytreea library that implements a generic tree structure.- Install with

pip install anytree.

- Install with

numpya library for linear algebra matrices manipulation.- Install with

pip install numpy.

- Install with

With the installation of the third party python libraries the installation of the application should be concluded. We provide two methods to check if everything is working. The first method is to run a simple experiment, the second regards the jupyter notebook, and it's valid only if you installed the (optional) jupyter notebook (see above).

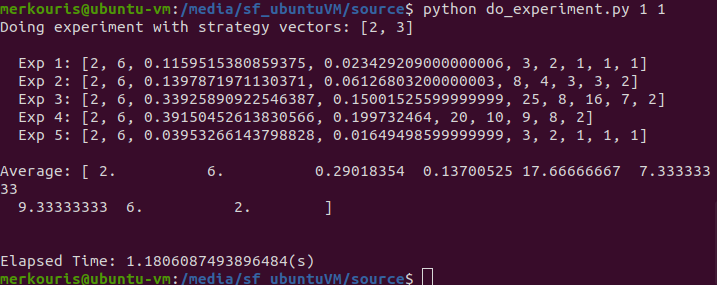

An easy way to see if everything went right is to go to the ./source directory and type

python do_experiments.py 1 1.

You should get the following,

The do_experiment.py runs a selection of experiments and outputs the generated statistics. The command python do_experiments.py 1 1 runs only the first experiment and outputs the statistics on the standard output. We will discuss the do_experiment.py file in more detail in a following Section.

If you have installed the jupyter notebook you can run the example in ./source/2x2_exam.ipynb. Simply, go to the ./source directory and type,

jupyter-notebook

The browser will open, with a catalogue of the ./source files. Select the 2x2_exam.ipynb. The example should be loaded. If you want, you can clear the kernel and run all the cells.

The above installation process was tested on a fresh Ubuntu 20.04.4 installation, on a virtual machine.

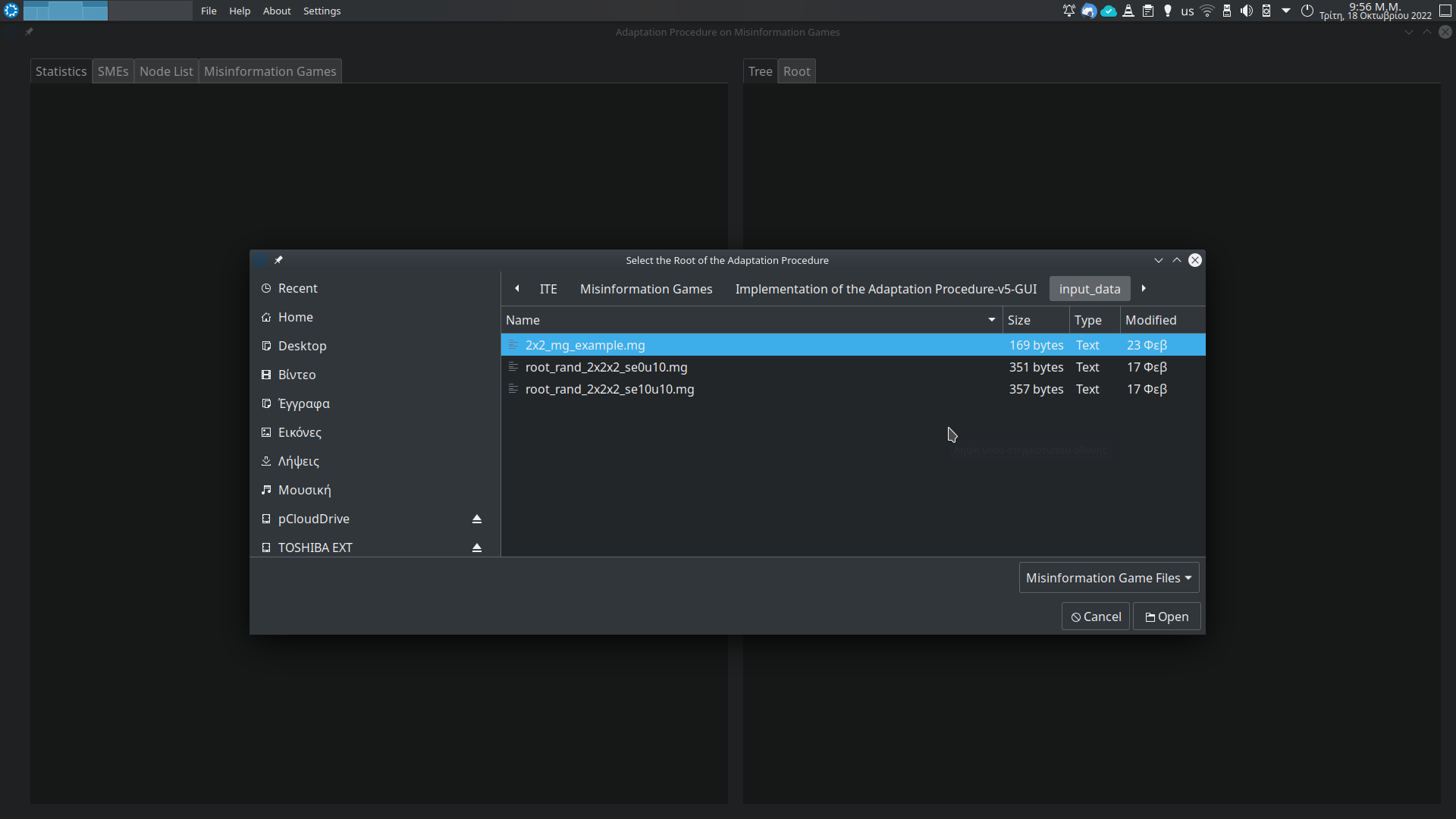

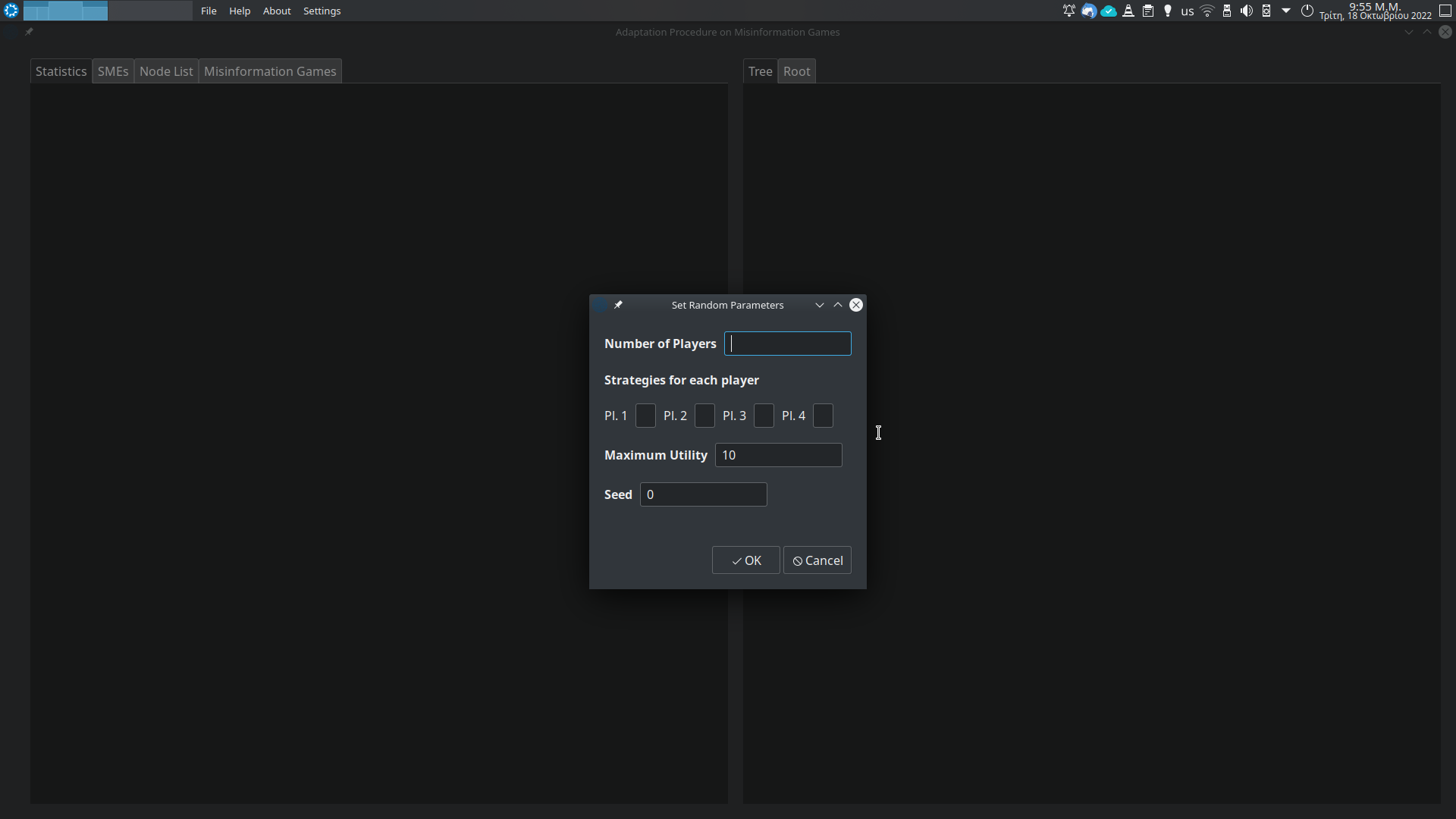

There are two ways to execute the program, the user can either provide a .mg file as input (see the Input subsection, below), or specify some parameters in order to generate a random instance. In either cases the execution takes place in ./source directory.

-

Input from file:

python main.py -f <path_to_input_file>For example, you may run the input file provided,

python main.py -f ../input_data/2x2_mg_example.mg. The provided input file should follow the.mgfile format, see below. -

Random generation:

python main.py -r <num_players> <strat_1> <strat_2> ... <strat_n> <max_util>Where,

<num_players>is the number of players,<strat_1> <strat_2> ... <strat_n>are the number of strategies for each player, and<max_util>is the maximum utility. For example,python -r 2 2 2 10will generate a random 2x2 misinformation, where the utilities are in set {0, 1, 2, ..., 10}.

The user should provide either -f <input_file>, or -r <params> as arguments. Otherwise, an error message will be outputed.

The arguments -f <input_file> and -r <params> are the only mandatory parameters. Additionally, a few other options are provided.

-fInitialise from file. E.g.:-f <mg_file_path>.-rGenerate random root file. E.g.:-r <num_players> <strat_1> <strat_2> ... <strat_n> <max_util>.-seInitialise the seed for the random generation. E.g.-se 0. The default value is0.-tPrint the Adaptation Tree (in text, on terminal).-roPrint the root on the terminal. Useful, when the root file is randomly generated.-stSave the Adaptation Tree in file. E.g.:-st <path_to_output.txt>.-lPrint a catalogue of the leaf nodes of the Adaptation Tree.-nPrint all the nodes of the Adaptation Tree.-mPrint the unique misinformation games.-smSave the unique misinformation games under a directory. E.g.:-sm <dir_path>.-ssSave the stable set (terminal set in the paper), the unique .mg files, under a directory. E.g.:-ss <dir_path>.-srSave the root to file. E.g.:-sr <path_to_output.mg>.-hHelp. Prints the list of arguments.-qQuiet. Suppresses the "about" header.-noSuppresses all output. Useful for the experiments.-fmFast mode. See paper. Implements a faster algorithm. While not the default hard coded operation mode, it is highly recommended. Otherwise, a (much) slower, naive method is executed.-mttMulti-thread Traversal. See section about Parallelism. E.g.-mtt <number_of_threads>specifies the number of threads to be used in the Adaptation Procedure. Only available in fast mode, i.e. the-fmargument must also be provided.-nemNash Equilibrium Method. Specifies the method to be used for finding Nash equilibria. E.g.-nem xpefor Extreme Point Enumeration. The supported methods also include: gnm (Generalized Newton Method), enp (Enumerate Pure Equilibria), pol (Support Enumeration). The default method ispol, i.e. Support Enumeration. Note that the methodxpeis available only in 2-player games.-dmnDomain. See the related section about Rounding Errors and Numerical Domains. Thus we specify the domain in which the strategy profiles of the GAMBIT will be mapped to. E.g.-dmn d 8, for using 8 decimals points. The supported methods are-dmn r(for real), for an arbitrary number of decimal points (using the GAMBIT's defaults), and-dmn v(for voronoi), for a more elaborate method using Voronoi diagrams. The "voronoi method" is explained in the Rounding Errors and Numerical Domains section.-dbgDebugging. See the related Debugging section. This arguments just provides additional information about the programs execution. It can be used along with two optional arguments.-dbg pwill print warning messages, if some error occur.-dbg dwill terminate the programs execution after the appearance of the first error. Of course, the two additional arguments can be combined, i.e.-dbg p d.

Note: We strongly suggest to always use the arguments -mtt 4 -fm, if your system has at least 4 hardware threads.

Consider the following .mg file ./input_data/2x2_mg_example.mg.

# 2x2_mg_example.mg

# number of players

2

# strategies

2 2

# game 0 utilities

1 -1

-1 1

-1 1

1 -1

# game 1: row player game

2 2

3 0

0 3

1 1

# game 2: column player game

2 1

0 0

0 0

1 2The .mg file should respect the following syntax.

The lines starting with # are comments and are discarded, by the program.

Note: The comments should be alone in a line. For example, 2 # number of players will provoke an error.

The first non-commended, non-empty line should be the number of players. In the above example we have 2 players.

The second non-commended, non-empty line should contain the strategies vector, i.e. <s1> <s2> ... <sn>, where <si> is the number of strategies of the i-th player, and n is the number of players given above. The number of strategies of each player is separated by spaces ' '.

The .mg file should contain n + 1 utilities dictionaries, which encode n + 1 normal form games. The first dictionary (the "0-th" game) is regarded as the actual (or objective) game. The i-th game is the subjective game of the i-th player. Each line contains a single payoff vector, the j-th number is the payoff of the j-th player. The sequence that the payoff vectors are written is fixed and follows the sequence that GAMBIT enumerates the strategy profiles (see here). The enumeration of the strategy profiles follows an "reverse" lexicographical order, e.g. (1, 1), (2, 1), (1, 2), (2, 2). Consider the first normal form game of the above file.

# game 0 utilities

1 -1

-1 1

-1 1

1 -1The first line corresponds to the strategy profile (1, 1), where both players play their first strategy, and player 1 gets 1 unit of utility, while player 2 gets -1 unit of utility. The second line corresponds to the strategy profile (2, 1), where the player 1 plays her second strategy, while player 2 plays her first strategy. Player 1 loses 1 unit of utility, while player 2 gains one. Etc.

Depending on the command line arguments the output will differ. The arguments that produce some output are the following:

-tOutputs the Adaptation Tree in text based "graphics".-roPrints the root file. Useful, when the root file is randomly generated.-lPrints the leaf nodes of the Adaptation Tree.-nPrints the Adaptation Tree nodes.-mPrints the unique misinformation games

We will give examples for every case and explain the difference of the outputs in fast and slow modes. In every case, we use the example file ./input_data/2x2_mg_example.mg.

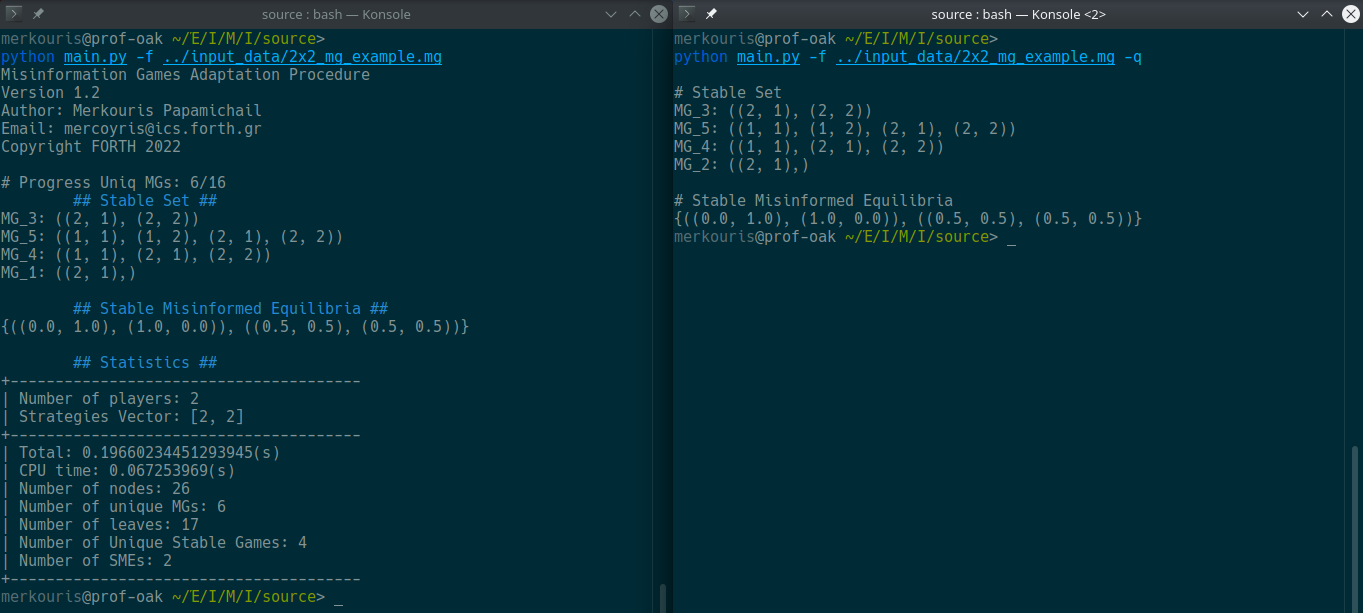

Firstly, we consider the output without arguments, apart the necessary arguments for input (i.e. -r or -f). This kind of output will be always printed, except when the argument -no, for "no output", is given.

When we type the command python main.py -f ../input_data/2x2_mg_example.mg we get the following.

$ ~/Έ/Ι/M/I/source> python main.py -f ../input_data/2x2_mg_example.mg

Misinformation Games Adaptation Procedure

Version 1.2

Author: Merkouris Papamichail

Email: mercoyris@ics.forth.gr

Copyright FORTH 2022

# Progress Uniq MGs: 6/16

## Stable Set ##

MG_3: ((2, 1), (2, 2))

MG_5: ((1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 1), (2, 2))

MG_4: ((1, 1), (2, 1), (2, 2))

MG_1: ((2, 1),)

## Stable Misinformed Equilibria ##

{((0.0, 1.0), (1.0, 0.0)), ((0.5, 0.5), (0.5, 0.5))}

## Statistics ##

+---------------------------------------

| Number of players: 2

| Strategies Vector: [2, 2]

+---------------------------------------

| Total: 0.19683361053466797(s)

| CPU time: 0.06513542500000001(s)

| Number of nodes: 26

| Number of unique MGs: 6

| Number of leaves: 17

| Number of Unique Stable Games: 4

| Number of SMEs: 2

+---------------------------------------The header consists of some information about this program. The next section describes the "stable" set (a more accurate term would be trerminal set, see paper) of the misinformation games, that were generated during the adaptation procedure. The "stable" set consists of the misinformation games that produce themselves, i.e. MG_3 we would have,

$$

MG_3 = ((MG_0){(2, 1)}){(2,2)}

$$

where MG_0 is the root misinformation game. The next section presents the Stable Misinformed Equilibria of the root misinformation game. Lastly, we output some statistics about the performance. The Total entry regard the total time consumed by the program including the time consumed by the subsystems, CLINGO and GAMBIT. The CPU time entry includes the time consumed only by the python code, excluding the subsystems. Observe that the python code consumes only 1/3 of the total time. The two subsystems, and especially GAMBIT, consist the bottleneck of the computation.

We make some remarks regarding the fast mode. Consider the following statistics, on the same input in fast mode.

## Statistics ##

+---------------------------------------

| Number of players: 2

| Strategies Vector: [2, 2]

+---------------------------------------

| Total: 0.16100573539733887(s)

| CPU time: 0.06466456699999999(s)

| Number of nodes: 16

| Number of unique MGs: 6

| Number of leaves: 9

| Number of Unique Stable Games: 4

| Number of SMEs: 2

+---------------------------------------Observe that the numbers of unique misinformation games, SMEs, and unique stable games is unchanged. On the other hand, the number of leaves and the number of nodes changes. Fast mode saves a lot of iterations by "cleverly" omitting some nodes of the Adaptation Tree, without lose of information.

The Adaptation Tree is printed with the argument -t. Observe in the figures bellow that the trees are different in slow and fast mode. the information that is encoded remains the same. Observe that if N_012, and N_021, we have mg_pool).

N_0, MG_0

├── N_01, MG_1

│ ├── N_011, MG_1

│ └── N_012, MG_3

│ ├── N_0121, MG_4

│ │ ├── N_01211, MG_4

│ │ ├── N_01212, MG_5

│ │ │ ├── N_012121, MG_5

│ │ │ ├── N_012122, MG_5

│ │ │ ├── N_012123, MG_5

│ │ │ └── N_012124, MG_5

│ │ ├── N_01213, MG_4

│ │ └── N_01214, MG_4

│ └── N_0122, MG_3

└── N_02, MG_2

└── N_021, MG_3

├── N_0211, MG_4

│ ├── N_02111, MG_4

│ ├── N_02112, MG_5

│ │ ├── N_021121, MG_5

│ │ ├── N_021122, MG_5

│ │ ├── N_021123, MG_5

│ │ └── N_021124, MG_5

│ ├── N_02113, MG_4

│ └── N_02114, MG_4

└── N_0212, MG_3N_0, MG_0

├── N_01, MG_1

│ ├── N_011, MG_1

│ └── N_012, MG_3

│ ├── N_0121, MG_4

│ │ ├── N_01211, MG_4

│ │ ├── N_01212, MG_5

│ │ │ ├── N_012121, MG_5

│ │ │ ├── N_012122, MG_5

│ │ │ ├── N_012123, MG_5

│ │ │ └── N_012124, MG_5

│ │ ├── N_01213, MG_4

│ │ └── N_01214, MG_4

│ └── N_0122, MG_3

└── N_02, MG_2

└── N_021, MG_3The application can print a catalogue of the leaf nodes with the argument -l. Note that each node of the adaptation tree contains a label (or pointer, see Wikipedia here). Two nodes may have a label to the same misinformation game.

## Leaves ##

| Node Name: N_012, MG_1

| Unique MG id: 1

| Previous NMEs Path: [(2, 1), (2, 1)]

| Unique Key: ((2, 1),)

| Node Name: N_0112, MG_3

| Unique MG id: 3

| Previous NMEs Path: [(2, 1), (2, 2), (2, 1)]

| Unique Key: ((2, 1), (2, 2))

[...]The record printed with the argument -l contains the entries:

-

Node Name, an identifier for the node and an identifier for the misinformation game this node "points" to. -

Unique MG id, the label to the misinformation game. -

Previous NMEs Path, the sequence of position vector that have been changed from the root misinformation game. -

Unique Key, the unique key, which consists of the position vectors in thePrevious NMEs Path, after we sort and remove the duplicates. While thePrevious NMEs Pathencodes a sequence of changes, theUnique Keyencodes a set. Observe that, the update of the positions$v_1, v_2$ from the root misinformation game, is identical with the upadate of the position vectors$v_2, v_1$ . Therefore, we can easily decide if two misinformation games are equivalent by checking theirUnique Keys.

The application can print the root file to the terminal with the argument -ro. The output also includes some comments, regarding some metadata of the misinformation game. This argument may be useful, when the application is initialised randomly.

## Root ##

# Misinformation Game: 0

# NMEs: dict_keys([((0.0, 1.0), (1.0, 0.0))])

# SMEs: set()

# num players

2

# strategies

2 2

# Game id: 0

# Nash Equilibria: [((1.0, 0.0), (0.0, 1.0))]

6 6

0 4

8 7

6 4

[...]The application can print a catalogue of the nodes with the argument -n.

## Nodes ##

| Node Name: N_0, MG_0

| Unique MG id: 0

| Previous NMEs Path: []

| Unique Key: ()

| Node Name: N_01, MG_1

| Unique MG id: 1

| Previous NMEs Path: [(2, 1)]

| Unique Key: ((2, 1),)

[...]Each record of this catalogue consists of the same entries as the records of the leaf nodes catalogue.

The application can print a catalogue of the (unique) misinformation games with the argument -m.

## MG Pool ##

| MG id: 0

| NMEs list: dict_keys([((0.0, 1.0), (1.0, 0.0)), ((0.0, 1.0), (0.0, 1.0)), ((0.0, 1.0), (0.333333, 0.666667))])

| Posistion Vectors: dict_values([[(2, 1)], [(2, 2)], [(2, 1), (2, 2)]])

| SMEs: set()

| Unique Key: ()

| MG id: 1

| NMEs list: dict_keys([((0.0, 1.0), (0.25, 0.75)), ((0.0, 1.0), (1.0, 0.0)), ((0.0, 1.0), (0.0, 1.0))])

| Posistion Vectors: dict_values([[(2, 1), (2, 2)], [(2, 1)], [(2, 2)]])

| SMEs: {((0.0, 1.0), (1.0, 0.0))}

| Unique Key: ((2, 1),)

[...]Each record of this catalogue consists of the following entries:

-

MG id, a unique id for each misinformation game. -

NMEs list, the list of the Natural Misinformed Equilibria (NME). An implementation of the function$NME(mG)$ , (see paper). -

Position Vectors, a list of the corresponding position vectors to the above NMEs. An implementation of the function$\chi(NME(mG))$ , i.e. $$ \chi(NME(mG)) = \bigcup_{\sigma \in NME(mG)} \chi(\sigma) $$ -

SMEs, the "direct" stable misinformaed equilibria of this misinformation game. An implementation of the function$SME(mG)$ . -

Unique Key, the unique key of the misinformation game. SeeUnique Keyentry in the-l(print leaves) command above.

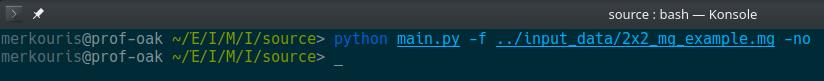

We also provide commands to suppress some (-q), or all (-no) of the output.

The quiet command forces a "terminal friendly" interface, that can be utilised from some parser script. Namely, the quiet command suppresses the "about" header of the output, while also suppresses the "progress bar" (e.g. the message # Progress Uniq MGs: 6/16), and the colours. This "mode" is useful when someone wants to process the output of our application with some other program. Forces all the output to be in simple ASCII text, while discards all the unnecessary messages. Observe that we keep the headers of each section of the results. Each section of the results, begins with the character #. This can be utilised from a parser in order to distinguish each section of data.

At the figure above we observe difference between a "vanilla" execution of the 2x2_mg_example.mg example file (left), and the execution of the same file with the -q argument (right).

On the other hand, the -no argument suppresses all output. It is designed to provide a "experiment friendly" interface. Note that the -no argument, doesn't suppress the "progress bar" (# Progress Uniq MGs: 6/16). This is useful for experiments on big instances, where the execution may take several minutes, or hours. Of course, the two arguments can be given together, i.e. -q -no. We give an example of the usage of -no bellow.

Because the output of the progress bar is overwritten, it is not visible in the above figure.

Experiments can be run with the do_experiment.py script.

python do_experiment.py <exp_1> <exp_2> (optional) <file_out>

Takes three arguments, the last of which is optional. The first two arguments are numbers in the range {0, 1, ..., 7}, and denote the experiments that will be run. E.g. for python do_experiment.py 0 3 will run the experiments 0 through 3. The experiments are the following:

02x2 misinformation game12x3 misinformation game23x3 misinformation game34x3 misinformation game44x4 misinformation game52x2x2 misinformation game63x2x2 misinformation game72x2x2x2 misinformation game

For each experiment, five games are randomly generated, with seeds the five first prime numbers, i.e. 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, and utilities in the range {0, 1, 2, ..., 10}. For each experiment we discard the first and the last game, and take the average for the remaining three (see the relative Section in paper).

Note:

- Only the first six (0-5) experiments are "feasible" and terminate in reasonable time (which can take up to a few hours).

- Another important thing to note is that the experiments are deterministic in some sense, since the seed of the random number generator is fixed for each experiment.

Here we give the outline of the code along with some extensive documentation on the important classes and functions. It is highly recommended to first read the attached paper (see ./documentation/SETN_final_named.pdf) and especially the section regarding the implementation, before proceeding to this documentation. This way the user will already have a high-level idea of how the implementation works. In this section we focus on the details of the implementation.

The source code of this project is located in the directory ./source and includes the following files:

- main.py: A Python 3 file. The "main function" (or root file) of the program. Its function is only to collect the command line arguments and direct them to the Application class, located at application.pl.

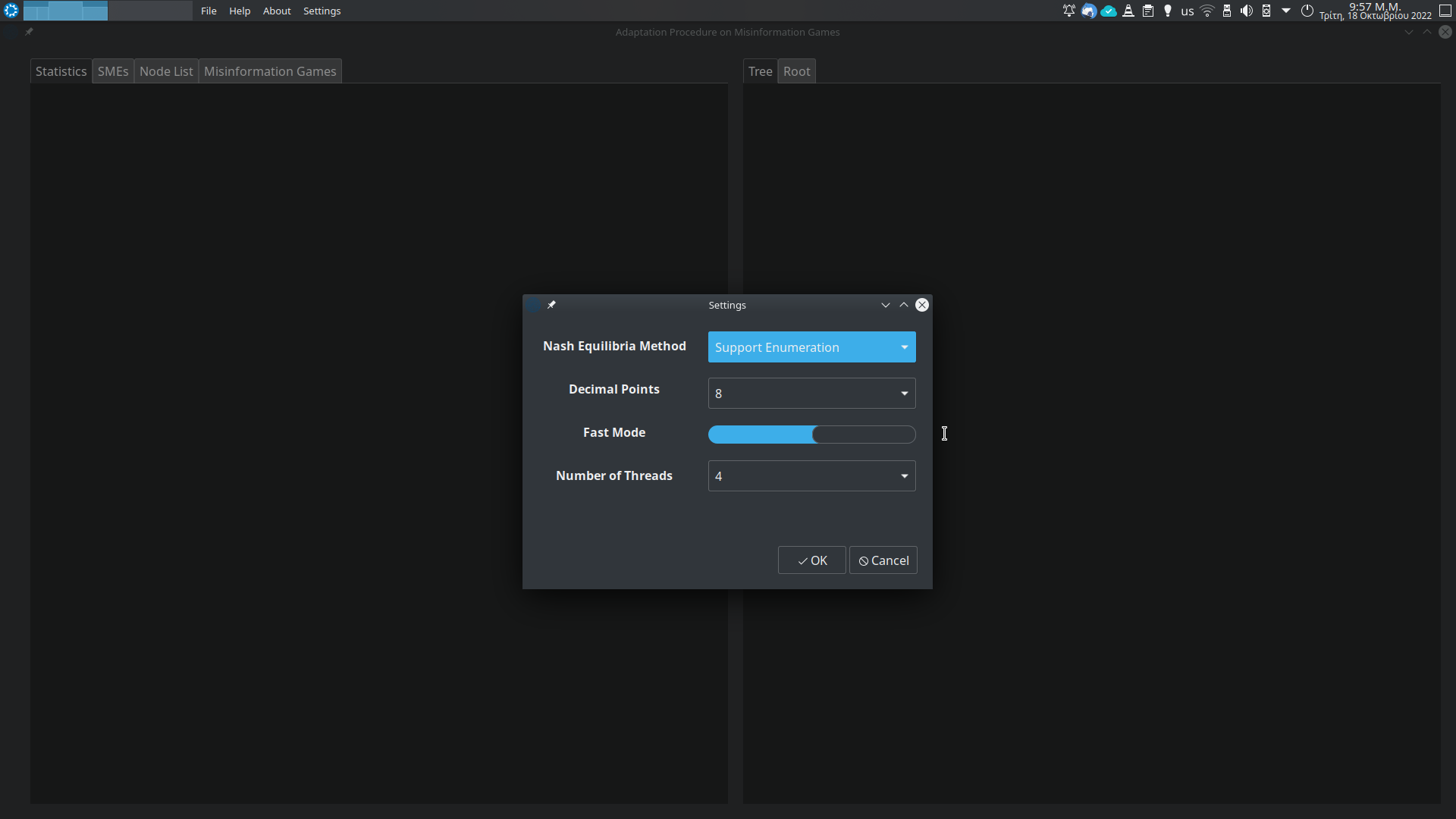

- gui_main.py: A Python 3 file. The "main function" (or root file) of the Graphical User Interface (GUI). The core functionality of the GUI is implemented in gtk_graphical_user_interface.py.

- application.py: A Python 3 file. Its function is to handle the command line arguments and make the correct calls to the methods of the AdaptationProcedure class located at adaptation_procedure.py. It functions as an intermediate layer between the user and the AdaptationProcedure.

- gtk_graphical_user_interface.py: A Python 3 file, using GTK 3.0. It implements the GUI, the style of the windows, menus, etc. We used the python interface for the GTK 3.0 library.

- application_process.py: A Python 3 file. Its function is to handle the communication between the GUI and the command line application. Recall, that the interface for the command line application is implemented in application.py.

- adaptation_procedure.py: A Python 3 file. It contains the AdaptationProcedure class which implements the adaptation procedure on a given misinformation game.

- misinformation_game.py: A Python 3 file. It contains the MisinformationGame class which encodes a misinformation game as a list of n + 1 normal form games, where n is the number of players.

- game.py: A Python 3 file. It contains the NormalFormGame class which encodes a normal form game, as a dictionary from the strategy profiles, to payoff vectors.

- clingo.py: A Python 3 file. It contains only a single function the

addaptation_step(). It handles the communication between the python code and the CLINGO language. It uses the CLINGO file adaptation.lp. - adaptation.lp: A CLINGO file. It contains the rules (or predicates) that implement the update operation on a misinformation game.

- misinformation_game.lp: A CLINGO file. It contains some auxiliary predicates for the adaptation.lp.

- gambit.py: A Python 3 file. It contains a single function the

support(). It handles the communication between the python code and the GAMBIT package. - parsers.py: A Python 3 file. It contains two functions that . parses the output of the GAMBIT package.

- params_vector.py: A Python 3 file. Implements the ParamsVector class, which is used in the communication between the GUI and the command line application. An instance of the ParamsVector class keeps the input to the command line application. The class instance will keep the parameters that specify the behavior of the adaptation procedure. The parameters have been collected from the GUI, and passed to the command line application as (plain) text.

- data_vector.py: A Python 3 file. Implements the DataVector class, which is used in the communication between the GUI and the command line application. An instance of the DataVector class keeps the output of the command line application to be send to the GUI, in order to be presented graphically.

- domain.py: A Python 3 file. Implements the SPDomain class, which implements the domain mapping (see relative section in the sequel). This class implements an experimental feature that aims to deal with the numerical (rounding) error that may appear in the GAMBIT's output data.

- debugging.py: A Python 3 file. Implements the Debugging class. This class collects measurements about the programs execution and provides a monitoring inteface. This class is responsible for the additional information provided when the command line application is called using the

-dbgargument. - auxiliary_functions.py: A Python 3 file. It contains some helper functions, that are used throughout the program.

- generate_random_clingo_mg.py: A Python 3 file. A script that generates (randomly) a CLINGO file that describes a misinformation game.

- 2x2_exam.ipynb: A Jupyter Notebook file. A presentation of the execution of a 2x2 example.

- do_experiment.py: A Python 3 file. It executes 8 experiments on the program and outputs some statistics. The user can specify which of the experiments to run.

- compare_methods.py: A Python 3 file. A script that compare different GAMBIT methods.

A Normal Form Game (NFG) is encoded in the NormalFormGame class, located in the ./source/game.py file.

The data members of the function are given in the following figure.

class NormalFormGame:

## Prelimineries

gambit_pac # The GAMBIT method to be used, for computing

# the Nash equilibria.

debugging # An instance of the Debugging class that keeps

# various metrics regarding the performance of

# the program.

domain # An instance of the SPDomain class that specifies

# the behavior of the program regarding floating

# point arithmetic.

## Data Members

game_id # String, the id of the NFG

num_players # Integer, the number of players

strategies # [Int], the strategies vector of the players

# the number of strategies for each player

utilities # Dict: (Int) --> [Int], a dictionary from the

# strategy profiles, to the payments vector

nash_equilibria # [(Int)], a list of tuples, ecoding the Nash

# Equilibria of the game

support # Dict: Int --> [Int], a dictionary from a player,

# to her support strategies

# States

strategy_profiles_generated # Bool

utilities_filled # Bool

nash_equilibria_computed # Bool

support_computed # BoolThe boolean data members in the above figure are used to keep truck of the preconditions and the state of the class's instance. The states ensure that the instance of the class follows a predetermined transition between the states, in order to ensure the correctness of each method. All the states are initialised in False.

We now describe the significant methods of this class in detail.

def __init__(self, gambit_pac, debugging, domain, game_id = "", num_pl = 0, strategies = []):The first three arguments of the constructor can be viewed as specifying our computational environment. The other three arguments specify the game id, the number of players, and the strategies vector. The later parameters have default arguments. Nevertheless, these default arguments are for technical purposes, it is advised, all the parameters to be given.

def generate_strategy_profiles(self):Generates the strategy profiles. Initialises the the keys of the utilities dictionary. For the values of this dictionary is used the empty utilities vector [].

Precondition: strategy_profiles_generated == False

Postcondition: strategy_profiles_generated == True

The first of the three ways to fill the utilities of a NFG.

def generate_random_utilities(self, max_utility):Generates random utilities, given that the strategy profiles are, already, generated. It takes a single argument, without a default value. The utilities will be generated in the range {0, 1, ..., max_utility}.

Precondition: strategy_profiles_generated == True and utilities_filled == False

Postcondition: utilities_filled == True

Note that this method does not edit the seed of the random number generator.

The second of the three ways to fill the utilities of a NFG.

def utilities_from_list(self, util_info_list):Fills the utilities of the NFG, given a utilities information list util_info_list. The utilities information list should have the following format.

[[Game, Player, (Int), Util]]

util_info_list is a list of lists, where inner list encodes an entry of the utilities dictionary. All the entries, i.e. Game, Player, Util are integers, while the tuple of integers (Int) encodes a strategy profile. Namely, an inner list of the form [Game, Player, SP, Util] encodes an instance, where player Player in the NFG Game and the strategy profile SP gets Util units of utility. This method is used from the MisinofrmationGame class, and the method utilities_from_clingo() (see the section Misinformation Game bellow). Note that the entry Game is discarted from the NormalFormGame class and is only used from the parent MisinformationGame class.

Precondition: strategy_profiles_generated == True and utilities_filled == False

Postcondition: utilities_filled == True

The last method to fill the utilities.

def utilities_from_str(self, lines):The above function is used for filling the utilities from a list of strings. This function is used by the grand-parent class AdaptationProcedure, when initialising the root misinformation game, from a file. Namely, for our standard example 2x2_mg_example.mg and for the actual 0 game, we would pass this function as argument the following,

["1 -1",

"-1 1",

"-1 1",

"1 -1"]Precondition: strategy_profiles_generated == True and utilities_filled == False

Postcondition: utilities_filled == True

def compute_nash_equilibria(self):Computes the Nash equilibria of the normal form game, using the GAMBIT package. It is here, where we use the gambit_pac attribute. We also use the debugging attribute to measure the time consumed by GAMBIT and domain to rectify GAMBIT's output (if needed) in order to avoid rounding errors.

Precondition: strategy_profiles_generated == True and utilities_filled == True and nash_equilibria_computed == False

Postcondition: nash_equilibria_computed == True

def compute_support(self):After computing the Nash equilibria we use this method to compute the support of the Nash equilibrium strategy profiles. With this function, the computation of a NFG is completed.

Precondition: strategy_profiles_generated == True and utilities_filled == True and nash_equilibria_computed == True support_computed == False

Postcondition: support_computed == True

def clingo_str_file(self):

str_file = self.str_vline("%") # a commend line "%%%%%%%"

str_file += self.str_header("%", "\n") # some commented metadata

str_file += self.str_vline("%") + "\n" # a commend line "%%%%%%%"

str_file += self.clingo_str_utility() + "\n" # the utilities predicate

return str_fileConverts the NFG to a description "readable" from the CLINGO programming language. For example the actual 0 game of the 2x2_mg_exam.mg would be translated in the following predicates.

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

% Game Id: 0

% Number of Players: 2

% Strategies: [2, 2]

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

u(0, 1, sp(1, sp(1, nul)), 1).

u(0, 2, sp(1, sp(1, nul)), -1).

[...]The information regarding the utilities is provided by the u/4 predicate. The predicate u(0, 1, sp(1, sp(1, nul)), 1) states the fact that in game 0, player 1 gets 1 unit of utility, in the strategy profile (1,1). We encode a strategy profile with a finite list of the form sp(1, sp(1, nul)), where we use the symbolic functions sp/2, and nul/0.

def gambit_str_file(self):

output = self.__gambit_str_prologue() + self.__gambit_str_body()

return outputOutputs the NFG in the .nfg format that can be read by GAMBIT. See here for the .nfg file format. It is important to note that the utilities are printed in a flat, comma separated list. The "reverse" lexicographical order that GAMBIT uses, is used throughout the application, when printing or reading strategy profiles and utilities.

We now give a minimal working example, for using this class as a stand alone module.

import game

# Prelimineries

import gambit

import debugging

import domain

gambit_pac = gambit.Gambit()

debugging = debugging.Debugging()

domain = domain.SPDomain()

id = "game_0"

num_players = 2

stategies = [2, 2]

NFG = game.NormalFormGame(gambit_pac, debugging, domain, id, num_players, strategies)

NFG.generate_strategy_profiles()

max_utilities = 10

NFG.generate_random_utilities(max_utilities)In the above example, we create a Normal Form Game of two players, each of them having two strategies. We fill the utilities randomly in range {0, 1, 2, ..., 10}.

A Misinformation Game (MG) is encoded in the MisinformationGame class, located in the ./source/misinformationgame.py file. A misinformation game is encoded as a list of normal form games.

The data members of the function are given in the following figure.

class MisinformationGame:

# Prelimineries

gambit_pac # The GAMBIT method to be used, for computing

# the Nash equilibria.

debugging # An instance of the Debugging class that keeps

# various metrics regarding the performance of

# the program.

domain # An instance of the SPDomain class that specifies

# the behavior of the program regarding floating

# point arithmetic.

# Data Members

game_id # Str, an identifier of the MG

num_players # Int, the number of players

strategies # [Int], the strategies vector

games # [NormalFormGame], a list of normal form games. If n

# the number of players, we would have n + 1

# misinformation games.

# The 0-th game is the actual (objective) game,

# while the other n are the subjective games of

# the players.

nme # Dict: NMEs --> PositionVectors. A dictionary

# from a NME to the corresponding position vectors.

sme # set(NMEs), the *set* of the NMEs of the game,

# that are Stable Misinformed Equilibria.

clingo_format # The clingo format of the MG

nme_clingo # Dict:NME --> [PosVec], a dictionary from a NME

# to the corresponding *predicates* of position

# vectors. The values would have the form,

# ["pos(<SP1>).", "pos(<SP2>).", .., "pos(<SPm>)."].

# States

utilities_generated # Bool

nme_computed # Bool

pos_vec_compiled # Bool

clingo_format_compiled # Bool

nmes_clingo_compiled # BoolThe boolean data members in the above figure are used to keep track of the preconditions and the state of the class's instance. The states ensure that the instance of the class follows a predetermined transition between the states, in order to ensure the correctness of each method. All the states are initialised in False.

def __init__(self, gambit_pac, debugging, domain, game_id, num_players, strategies):The first three arguments of the constructor can be viewed as specifying our computational environment. The gambit_pac, debugging and domain instances are passed directly to the NormalFormGame subclasses. The other three arguments, game_id, num_players, and strategies, specify the instance behavior. Note that, the arguments are identical to those of a NormalFormGame instance. The game_id is a string. The num_players is an integer, while the strategies is a list of integers describing the strategies vector.

The constructor, call the constructor of all the n + 1 NFGs and generates their strategy profiles, i.e. the method NormalformGame::generate_strategy_profiles() is called. Hence the state variable NFG.strategy_profiles_generated is True for each of the n + 1 NFG.

One of the two ways to fill the utilities.

def generate_random_utilities(self, max_utility):Generates random utilities for the every strategy profile, and every player. It iteratively calls the method NormalFormGame::generate_random_utilities(max_utility).

Precondition: utilities_generated == False

Postcondition: utilities_generated == True

Note that this method does not edit the seed of the random number generator.

The second and last method to fill the utilities

def utilities_from_clingo(self, answer_set):Computes the utilities of the Answer Set of CLINGO. The answer_set is passed as a simple string. This method calls the NormalFormGame::utilities_from_list() of the NFGs.

Precondition: utilities_generated == False

Postcondition: utilities_generated == True

Note that there is no method to initialize the utilities from file. This is because of technical reasons. The class AdaptationProcedure which initialises an instance of a MG from the above mentioned .mg file format. This is achieve with direct calls to the grand-child's method NormalFormGame::utilities_from_str(). In deed this is not an elegant design and prevents the easy usage of the MisinformationGame as stand alone class.

def compute_knowledge_from_answer_set(self, answer_set):When the utilities are initialized from the CLINGO answer set this method is invoked automatically. It parses the information existing in the answer set regarding the agents' social knowledge in this misinformation game. For a more in depth analysis of the notion of knowledge in misinformation games see the related section titled Agents' Knowledge.

def compute_nme_dict(self):Computes the NMEs of the misinformation game. Calls the method NormalFormGame::compute_support(), despite the fact that only uses the Nash Equilibria generated from the compute_support() method. Note that the NMEs are mixed strategy profiles. This method initialises the dictionary nme (see Data Members). The key values of this dictionary are the NMEs generated, while the values are set to the empty list [].

Precondition: nme_computed == False

Postcondition: nme_computed == True

Note: Since this function calls the NormalFormGame::compute_support(), this parent function implicitly calls the GAMBIT subsystem. For each call of MisinformationGame::compute_nme_dict(), there are n + 1 calls to NormalFormGame::compute_support(), hence n + 1 calls to GAMBIT.

Issues: See issues section, regarding the design of this method. No (known) issues in functionality.

def compute_pos_vecs(self):From the NMEs computes the position vectors, and fills the nme dictionary. Note that a NME is a vector of vectors. For some NME

Precondition: nme_computed == True and pos_vec_computed == False

Postcondition: pos_vec_computed == True

def clingo_compile_format(self):Compiles (computes) the description of the MG in CLINGO predicates. Calls the method NormalFormGame::clingo_str_file() in order to produce this description.

Precondition: utilities_generated == True and clingo_format_compiled == False

Postcondition: clingo_format_compiled == True

Notes: The child function NormalFormGame::clingo_str_file(), with the predicates for the utilities, also generates some comments regarding the metadata of the NFG. These comments are useful, when the child method is used stand alone, but unnecessary when the exported file is only read by CLINGO.

def clingo_compile_nme(self):This function computes a list of predicates of position vectors corresponding to NMEs. The name is somewhat unfortunate. If (1, 2, 3) some position vector, the we would have the predicate,

pos(sp(1, sp(2, sp(3, nul)))).

Precondition: nme_computed == True and pos_vecs_computed == True and nmes_clingo_compiled == False

Postcondition: nmes_clingo_compiled == True

Issues: See issues section. Unfortunate name. No known issues regarding the functionality.

def initialization_completed(self):

return self.utilities_generated == True and\

self.nme_computed == True and\

self.pos_vecs_computed == True and\

self.clingo_format_compiled == True and\

self.nmes_clingo_compiled == TrueThe above predicate check whether the initialisation of the class is completed.

The list sme is not filled by methods of this class. This data member is handled by the AdaptationProcedure class.

We now give a minimal working example, for using this class as a stand alone module.

import misinformation_game as mg

# Prelimineries

import gambit

import debugging

import domain

gambit_pac = gambit.Gambit()

debugging = debugging.Debugging()

domain = domain.SPDomain()

id = "mg_0"

num_players = 2

strategies = [2, 2]

MG = mg.MisinformationGame(gambit_pac, debugging, domain, id, num_players, strategies)

max_utility = 10

MG.generate_random_utilities(max_utility)

MG.compute_nme_dict()

MG.compute_pos_vecs()

MG.clingo_compile_format()

MG.clingo_compile_nme()In the above example we create a misinformation game MG, with id = "mg_0", num_players = 1 and strategies vector strategies = [2, 2]. Next we generate the utilities randomly, in the range {0, 1, 2, ..., 10}. Lastly, we fill all the data structures and the data members of the class.

The file adaptation_procedure.py includes two classes the AdaptationNode and the AdaptationProcedure. This module implements two algorithms for the Adaptation Procedure, the naive "slow" mode, and the more elaborate "fast" mode.

We present the data members of the class AdaptationNode first.

class AdaptationNode(NodeMixin): # expands the class NodeMixin

# used by the anytree module

# Data Members

node_id # Str, an identifier

name # Str, some identifier, used by NodeMixin.

parent # Pointer to the parent AdaptationNode

# (used by NodeMixin)

misinformation_game # Pointer to a misinformation game

nme_path # a list of *position vectors*

unique_key # a tuple encoding a set of the

# position vectors* that have been updated

# Flags

changed_from_parent # Bool, a flag encoding whether *this*

# MG have been changed from the parent MG.

new_mg # Bool, a flag encoding whether this MG

# was generated for this node, or we

# encondered an already visited

# misinformation game.The module anytree and especially the class NodeMixin are used in order to render the (text based) graphics for the Adaptation Tree. The documentation for this third party library can be found here.

Next, we present the data members of the AdaptationProcedure class.

class AdaptationProcedure:

# Prelimineries

gambit_pac # The GAMBIT method to be used, for computing

# the Nash equilibria.

debugging # An instance of the Debugging class that keeps

# various metrics regarding the performance of

# the program.

domain # An instance of the SPDomain class that specifies

# the behavior of the program regarding floating

# point arithmetic.

# Data Members

mis_game_pool # Dict: unique_keys --> MGs, a dictionary from

# the unique keys, see above, to the corresponding

# Misinformation Game.

uniq_mg_counter # Int, just a counter that (well) counts the unique

# misinformation games. Note that we would have,

# uniq_mg_counter = |mis_game_pool.values()|

mis_game_lock # A threading.Lock that controls the access to the

# mis_game_pool. We use this lock for threads

# synchronization.

queue # [AdaptationNode], the BFS queue.

queue_lock # A threading.Lock that controls the access to the

# queue. We use this lock for threads

# synchronization.

queue_empty # A threading.Condition that uses queue_lock. We use

# this condition variable to wake the threads waiting

# the queue_lock.

terminal_set # set(MisinformationGame), in the paper we call this

# the *Terminal Set*. Are the MGs that produces themselves

# in a single step.

terminal_set_lock # A threading.Lock that controls the access to the

# terminal_set. We use this lock for threads

# synchronization.

smes # set((Int)), a set of tuples. The tuples correspond to

# the SMEs of the root MG.

smes_lock # A threading.Lock that controls the access to the

# smes. We use this lock for threads

# synchronization.

root # MG, the root misinformation game

node_list # [AdaptationNode], just a record of the AdaptationNodes

node_list_lock # A threading.Lock that controls the access to the

# node_list. We use this lock for threads

# synchronization.

# Statistics

cpu_time # Float, the time (in seconds) consumed by the python

# program, excluding the time consumed by the subsystems.

total_time # Float, the total time consumed by the application,

# *including* the time consumed by the subsystems.

max_knowledge # Int. the maximum knowlege the agents reached throughout

# the adaptation procedure

max_knowledge_mg_id # String. the Id of the misinformation game where the

# agents reach the maximum knowledge.

# Multithreading

tasks # Int. the number of *pending* tasks, Each time a thread creates

# a new task, the value of the variable is increased. On the

# other hand, if a thread *consumes* (or serves) a task, the

# value of the variable is decreased. While there are still

# pending taks (the adaptation procedure has not concluded)

# we have tasks > 0.

tasks_lock # A threading.Lock that controls the access to the

# tasks. We use this lock for threads

# synchronization.

pending_tasks # A threading.Condition that uses tasks_lock. We use

# this condition variable to wake the threads waiting

# the tasks_lock.

# States

root_initialized # Bool

adaptatio_procedure_completed # BoolSince the AdaptationNode class is only used by the AdapatationProcedure class, and only contains accessors and modifiers, we only present the constructor of the AdaptationNode class, and then we proceed with most important methods of the AdaptationProcedure class.

def __init__(self, node_id, nme_path, unique_key, MG, parent = None, changed_from_parent = True, new_mg = True):The adaptation node constructor takes as arguments the values for the data members of the class. The default values are only used when we construct the root Adaptation Node. Note that the two flags, changed_from_parent and new_mg are used from the method AdapationProcedure::adaptation_substep(), see bellow. Apart from the root, each node should have a parent. The data member name (see above) is filled by the fields node_id and the MG.game_id, respecting the following format, self.name = "N_" + node_id + ", MG_" + MG.get_game_id().

Note: There are no preconditions for creating an Adaptation Node. Perhaps an obvious precondition would be (and indeed was in an older version of the program), but we allow Adaptation Nodes to be constructed that reference Misinformation games where the utilities have not been computed yet. By doing this we achieve full parallelization (see the related section titled Parallelism).

def __init__(

self,

gambit_pac,

debugging,

domain,

num_mult_threads_traversal = 4,

quiet = False,

fast_mode = False

)Note that here (as we saw in the previously described classes) the computation environment is specified in the arguments gambit_pac, debugging and domain. We also provide the number of threads to be used, and flags for being or not in fast_mode, and printing or not the progress bar (i.e. quiet).

The first of the two methods to initialise the adaptation procedure.

def root_from_file(self, file_fmt):The above method needs a single argument file_fmt which is the string of the .mg file format (see the Input section above). This methods uses directly the NormalFormGame::utilities_from_str() of the grand-child class.

Precondition: root_initialized == False

Postcondition: root_initialized == True

Note: In these initialisation methods, and the method new_mis_game() (see bellow), we call all the necessary methods to completely initialise the MG, i.e. we have MG.initialization_completed() == True.

The second method to initialise the adaptation procedure.

def root_random(self, num_players, strategies, max_utility):The above method needs three arguments, the num_players which is an integer denoting the number of players, the strategies a list of integers which denotes the strategies vector, and the max_utility an integer needed for the random number generator. This method utilises the MisinformationGame::generate_random_utilities(max_utility), and generates the utilities in the range {0, 1, 2, ..., max_utility}.

Precondition: root_initialized == False

Postcondition: root_initialized == True

Note: In these initialization methods, and the method new_mis_game() (see below), we call all the necessary methods to completely initialize the MG, i.e. we have MG.initialization_completed() == True.

def _new_mis_game(self, parent, new_unique_key, pred_pos_vec):Creates a new misinformation game and adds it to the mg_pool data structure. Takes three arguments. The first arguments parent is a "pointer" to a AdaptationNode, this pointer is only used to access the data members num_players, strategies etc. in order to initialise the MG. The second argument, new_unique_key is used to "save" the MG to the mg_pool dictionary. The pred_pos_vec is a CLINGO predicate, we use this predicate to invoke the CLINGO subsystem and apply the update operation (see paper). From the CLINGO subsystem we obtain the answer set containing the utilities for the new misinformation game.

Notes:

- This is the only method (apart from the root initialisation) where the counter

uniq_mg_counteris increased,self.uniq_mg_counter += 1. - This is the only method of the Adaptation Procedure class, where we make GAMBIT and CLINGO calls.

def _adaptation_substep(self, node_id, parent, tuple_pos_vec, changed_from_parent, pred_pos_vec):This is perhaps the most important method of the AdaptationProcedure class. Takes five arguments. The first node_id is the id of the child node. The parent is the parent AdaptationNode. The third argument tuple_pos_vec is the position vector that will be updated from the parent to receive the child node. The fourth argument, changed_from_parent is quite self-explanatory; it denotes a boolean function that is True if and only if the resulting misinformation game has changed from its parent. The last argument, pred_pos_vec is the CLINGO-predicate of the position vector tuple_pos_vec.

We have three cases:

Case 1: The child is a copy of its parent.

if not changed_from_parent:

parents_MG = parent.get_mg_pointer()

return AdaptationNode(node_id, new_path, parents_unique_key, parents_MG, parent, False, False)If the resulting misinformation game will not be different from its parent, we omit computing it. We just create a new Adaptation Node that points to the (already computed) parent misinformation game. Also, if the child is equal to its parent, then the NME corresponding to the position vector tuple_pos_vec is a potential SME. Thus, we differentiate this case from the next.

Case 2: The child differs from its parent, but equals to another misinformation game, computed in another branch of the Adaptation Tree.

if self.mg_already_computed(new_unique_key):

MG = self.mis_game_pool[new_unique_key]

return AdaptationNode(node_id, new_path, new_unique_key, MG, parent, True, False)In this case, we just check if the new_unique_key is already computed. Note that the new_uniq_key essentially is a (sorted) sequence of the pieces of information that the agents know at the moment. In other words, new_uniq_key encodes the set of position vectors that have resulted to this misinformation game; we sometimes refer to this structure as "position vector history". The set of uniq_keys is isomorphic to the set of misinformation games. Hence, we can check if we have already computed the child, without computing the child. Namely, we claim the following equation holds.

$$

mG_1.\mathtt{position_vec_history()} = mG_2.\mathtt{position_vec_history()} \Leftrightarrow mG_1 = mG_2

$$

The details about why the above equation holds are provided in the section about Parallelism1.

In this case, again, we do not create a new misinformation game. On the other hand, we create just an Adaptation Node that points to the already existing misinformation game mis_game_pool[new_uniq_key].

Case 3: We have a new misinformation game.

new_MG = self._new_mis_game(parent, new_unique_key, pred_pos_vec)

return AdaptationNode(node_id, new_path, new_unique_key, new_MG, parent, True, True)This is the only case, where we create a new misinformation game, and we do that only if we encounter a misinformation game for the first time. Observe that only in this case we call the method AdaptationProcedure::new_mis_game().

def _adaptation_step(self, parent):Given a parent node this method will compute a step of the Adaptation Procedure. Namely, given a parent node

-

Create Requests: We create tuples of the form:

( request_parent, # a pointer to the parent node request_nme, # the NME as tuple of real numbers tuple_pos_vec, # a pos. vec. corresponding to the NME, # as tuple of integers pred_pos_vec # the pos. vec. as a clingo predicate )

We use these requests to check wheather the resulting MG, when the update operation is applied, is a) different of its parent and b) to compute the new MG.

-

Handle Requests: In this step we invoke the

_adaptation_substep()method. This method decides whether this branch will be stopped, i.e. the node will be added as leaf, and the child will not be added back to queue; or we will continue the adaptation procedure, in which case we add the child back to the queue. -

Compute SMEs Using the

changed_from_parentbit we decide whether the NME we take in consideration, is an SME. Recall that an NME is an SME is all the position vector that correspond to the NME do not result in a new NME.

def adaptation_procedure(self):This method just starts the working threads.

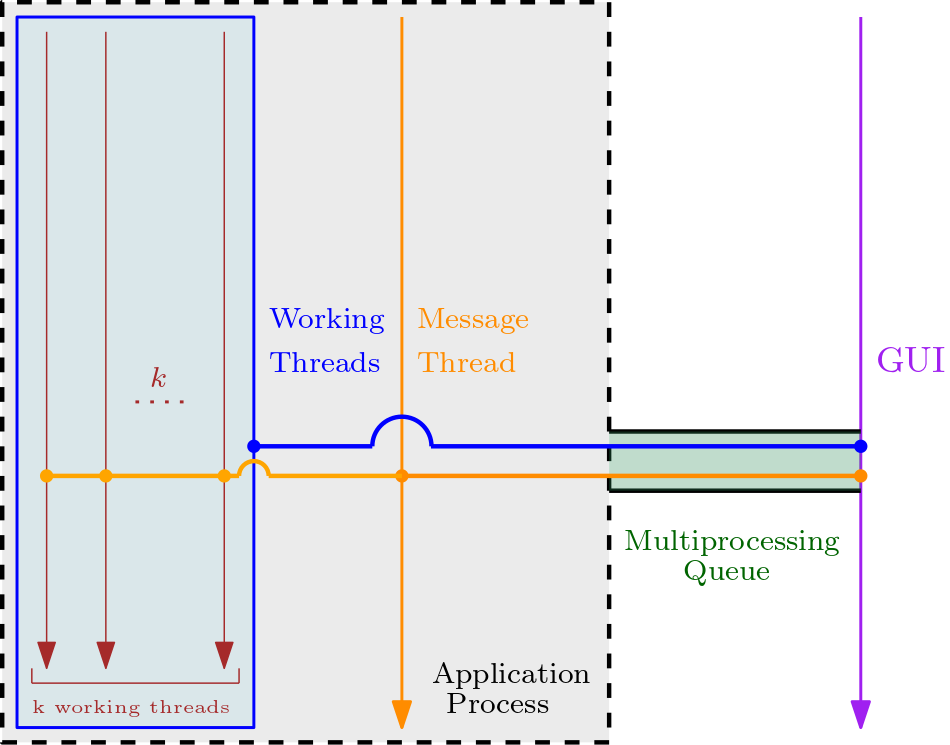

for i in range(self.num_mult_threads_traversal): self.workers[i].start()def traversal_thread_operate(self):This is the target function of the threads. This method is essentially "consumes" an adaptation node from the queue, and applies the adaptation_step(). In this method takes place the core of the thread synchronization, using locks and condition variables. For the thread handling we use the threading python library, i.e. the threading.Lock() object and the threading.Condition() object. The threads, while the variable traversal_threading_operation_on is True will try and acquire the queue_lock and consume an adaptation node. With this node as parent will call the _adaptation_step() method. Inside, the adaptation method, is new nodes are added in the queue, the tasks variable will be increased. On the other hand, inside the traversal_thread_operate() method the tasks variable will be decreased by 1, since the thread achieved consuming a node. The tasks variable is essential for the threads synchronization, as we will see in the sequel.

def wait_for_results(self):This method is used by the Application class which calls the methods of the Adaptation Procedure class. It is used to make the Application wait for the Adaptation Procedure to be concluded. Due to the parallelism this is not a simple task. The queue of the adaptation procedure could be empty, but the Adaptation Procedure could not be concluded. In other words, assume that we have at least 2 threads, namely T1 and T2. Also, assume that the queue has only one node (this of course is the case at the beginning of the procedure, when the queue only includes the root). Now, T1 achieves to access the queue and consumes the node. On the other hand, T2 will wait on the condition variable queue_empty, since the queue is now empty. On the other hand, there is still useful work to be done, namely T1 will compute the children of the node and add the to the queue. In no case, we want the Adaptation Procedure to be stopped. We want the Application class to still wait for the results.

In order to achieve this, we use the tasks variable. The tasks variable contains the correct measurement regarding the existence of useful work to be done. In the above scenario we will have tasks > 0. Let the node that is handled by T1 to have adaptation_step(), T1 will increase the number of tasks to be done to tasks = tasks + n. At the end of an iteration of the traversal_thread_operate(), and after the tasks variable is (potentially) increased, only then we decrease the tasks tasks = tasks - 1, since we consumed a node at the beginning of the iteration.

From the above, we hope to be obvious, that the application class should wait while tasks > 0. This is exactly, how we implement the wait_for_results() method:

self.tasks_lock.acquire()

while self.tasks > 0:

self.pending_tasks.wait()

self.tasks_lock.release()

self.adaptation_procedure_completed = Truedef turn_off(self):After, the wait_for_results() method returns, the Application class calls the turn_off() method. Note that, when the queue is finally empty and we have no pending tasks, i.e. tasks == 0, all the threads will be waiting. Thus, the Application should turn them off. We do that by essentially setting the variable traversal_threading_operation_on to False. Then, wake up the threads, in order for them to return. This is achieved by the following code (in tunr_off() method).

self.traversal_threading_operation_on = False

self.queue_lock.acquire()

self.queue_empty.notify_all()

self.queue_lock.release()On the other hand, from the code bellow (which resides in traversal_threading_operate()) the threads will return (exit):

## If you woke from waiting, with an empty queue return

if self.queue == [] and not self.traversal_threading_operation_on:

self.queue_lock.release()

returnFor more information about the way our parallel algorithm works, see the related section about Parallelism.

We give two minimal examples for the AdaptationProcedure class.

The first example regards the initialisation of the root node from a file.

import adaptation_procedure as ap

# Prelimineries

import gambit

import debugging

import domain

# Computation Enviroment

gambit_pac = gambit.Gambit()

debugging = debugging.Debugging()

domain = domain.SPDomain()

# Execution Parameters

num_mult_threads = 4

quiet = False

fast_mode = True

# Game Parameters (Open File)

f = open("../input_data/2x2_mg_example.mg", r)

file_fmt = f.read()

f.close()

# Create an empty Adaptation Procedure

adapt_proc = ap.AdaptationProcedure(

gambit_pac,

debugging,

domain,

num_mult_threads,

quiet,

fast_mode

)

# Initialize from File

adapt_proc.root_from_file(file_fmt)

adapt_proc.adaptation_procedure() # run the procedure in parallel

adapt_proc.adapt_proc.wait_for_results() # wait for the results

adapt_proc.adapt_proc.turn_off() # terminate the threadsIn the above example, we initialise the adaptation procedure from the file ./input_data/2x2_mg_example.mg

The second example regards the random generation of the root adaptation node.

import adaptation_procedure as ap

# Prelimineries

import gambit

import debugging

import domain

# Computation Enviroment

gambit_pac = gambit.Gambit()

debugging = debugging.Debugging()

domain = domain.SPDomain()

# Execution Parameters

num_mult_threads = 4

quiet = False

fast_mode = True

# Game Parameters

num_players = 2

strategies = 2

max_util = 10

# Create an empty Adaptation Procedure

adapt_proc = ap.AdaptationProcedure(

gambit_pac,

debugging,

domain,

num_mult_threads,

quiet,

fast_mode

)

# Initialize Randomly

adapt_proc.root_random(num_players, strategies, max_util)

adapt_proc.adaptation_procedure() # run the procedure in parallel

adapt_proc.adapt_proc.wait_for_results() # wait for the results

adapt_proc.adapt_proc.turn_off() # terminate the threadsIn the above example, we created a random 2x2 misinformation game, with the utility values in the range {0, 1, ..., 10}.

The two subsystems are handled as sub-processes by the python's code. See here, for more information regarding suprocesses in python.

The parameters for the spawn of the CLINGO subprocess are setted in the file clingo.py

def addaptation_step(clingo_mg_file, clingo_nme, clingo_axioms="./adaptation.pl"):This file contains a single function called addaptation_step() (misspelled). This function takes three arguments. The first is a string containg the description of a misinformation game in predicates. The second argument, also a string, contains a single predicate which provides a position vector, i.e. pos(<pos_vec>). The last argument is a CLINGO file containing the axioms (or rules) describing the update operation.

Note: We can determine the number of threads to make available for the CLINGO compiler. The default setting, we choose is 4.

clingo_call = subprocess.run(

[

"clingo",

"-t",

"4"

],

stdout=subprocess.PIPE,

text=True,

input=input

)This can be changed by changing the value in line 5.

The GAMBIT subsystem in defined in the gambit.py file. There, we define the Gambit class. The Gambit class is initialized as following.

def __init__(self, decimal = 8, method_val = method_vals.pol_val, timeout = 1):The first parameter defines the accuracy, i.e. the number of decimal points. The second parameter specifies the method used to compute the Nash equilibria. As the default method, we use the Support Enumeration, i.e. the gambit-enumpoly command. The last parameter specifies the timeout, i.e. the time interval we allow the GAMBIT command to run, before we terminate it. The default value used is 1 second. From the experiments we observed that this is a sufficient (enough) interval.

The parallel version of the implementation can be invoked using the -mtt <num_threads> (where mtt stands for "multi-threading traversal"). The parallel implementation is optimal in the sense that, when k threads are given, then the code will run k times faster. We will try to establish this claim in the sequel.

Notes: Parallelism is available only in fast mode. When the argument -mtt is given without providing the argument -fm, an error message will be printed. The above constraint is due to the structure of the parallel algorithm, and cannot be lifted. We will also establish this claim in the sequel.

It is important to understand in depth the purpose of our algorithm. Perhaps the pseudocode presented in the paper is somewhat oversimplified. Our algorithm traverses the adaptation graph, in order to compute the SMEs, but in order to do that, and guarantee that all the SMEs will be (eventually) discovered, we need to assert the following conditions:

- Let

$\mathcal{AD}^\infty(mG_0)$ be the set of all misinformation games that appear in an adaptation procedure on$mG_0$ . We have to explore the whole$\mathcal{AD}^\infty(mG_0)$ , namely to make sure that our algorithm doesn't omit any nodes of the adaptation graph. - Let

$E_{mG}$ be the adaptation relation on$\mathcal{AD}^\infty(mG_0)$ . Namely, for some$mG_1, mG_2 \in \mathcal{AD}^\infty(mG_0)$ , such that there exists some position vector$\vec{v} \in \chi(NME(mG_1))$ , with $mG_2 = (mG_1){\vec{v}}$, we have $(mG_1, mG_2) \in E{mG}$. In other words, the relation$E_{mG}$ contains all the pairs of misinformation games$mG_1, mG_2$ , such that we can arrive from$mG_1$ to$mG_2$ with a single update operation.

If we let, compute_children() that given a misinformation games, computes its children. We will analyze in more detail the compute_children() method in the sequel. For now, let us write a version of the BFS method adjusted for our setting.

V <-- {} // the set of vertices

E <-- {} // the set of edges

Q <-- {root_mG} // the BFS queue

while Q != {}:

parent_mG <-- Q.pop()

parent_mG.compute_children()

for each child_mG in parent_mG.get_children():

if child_mG not in V:

V <-- V U {child_mG}

Q,insert(child_mG)

if (parent_mG, child_mG) not in E:

E <-- E U {(parent_mG, child_mG)}

return G = (V, E)

For the above algorithm, we have that our aim is to construct the graph, rather than explore it. Also, note that in each step, we either discover a new node or a new relation. When we discover a new node, we always discover a new relation, the opposite does not necessarily hold. On the other hand, we insert only new nodes to the queue Q.

As we established in the paper, we can transfer all of the above notions, i.e. the adaptation graph, from the misinformation game setting to position vector strings. In other words, we can define an isomorphism from get_pos_history(), which returns the sequence of position vectors that have been updated from the root, namely, the pieces of information the agents learned from the beginning of the procedure. In this direction, we change the definition of the symbol V, whose function is to keep the misinformation game we have computed, from a set, to a dictionary. Additionally, we change the definition of the symbol E, from a relation on misinformation games to a relation on position vector strings.

From the above we give a more detailed version of our algorithm.

Q <-- {root} // BFS queue

V <-- {} // the set of visited mGs

E <-- {}

while Q != {}:

parent_mG <-- Q.pop()

for each pos_vec in parent_mG.get_pos_vecs():

if is_new_mg(parent_mg, pos_vec, parent_mG.get_pos_vec_history(), V):

child_mG <-- update_operation(parent_mG, pos_vec) // CLINGO call (expensive call)

V[[pos_vec | parent_mG.get_pos_vec_history()]] = child_mG // update the dictionary

child_mG.compute_pos_vecs() // GAMBIT call (very expensive call)

E.insert((parent_mG, child_mG))

Q.append(mG')

else:

child_mG <-- V[[pos_vec | parent_mG.get_pos_vec_history()]]

E.insert((parent_mG, child_mG))

Observe, that we broke the computation of the children in two steps. At first we compute the position vectors of a misinformation game, with compute_pos_vec() method. This method essentially implements the composition of the functions update_operation() method, which takes as argument a parent misinformation game and a position vector, and returns a new misinformation game. Lastly, with [head|tail] we denote a list with head as head and tail as tail.

An important thing to note is the existence of the is_new_mg() method. This method takes as argument a position vector (of the parent), the position vector history of the parent and the dictionary V, and checks weather the position vector sequence [pos_vec | parent_mG.get_pos_vec_history()] will result on a new misinformation game. How can we implement the is_new_mg() predicate? Observe that there are two cases. The first one is when the sequence of position vectors has already been computed, i.e. the key [pos_vec | parent_mG.get_pos_vec_history()] exist in the dictionary V. On the other hand, the sequence could not be already computed, but the update operation result in the same misinformation game, i.e. update_operation(parent_mG.get_pos_vec_history(), pos_vec) = parent_mG. This could happen because the piece of information denoted by pos_vec belongs to the a priori knowledge of the agents. Namely, the players have are correct about their payoffs in the strategy profile corresponding to pos_vec, before the adaptation procedure begins. We can reduce this second case to the first, by preprocessing.

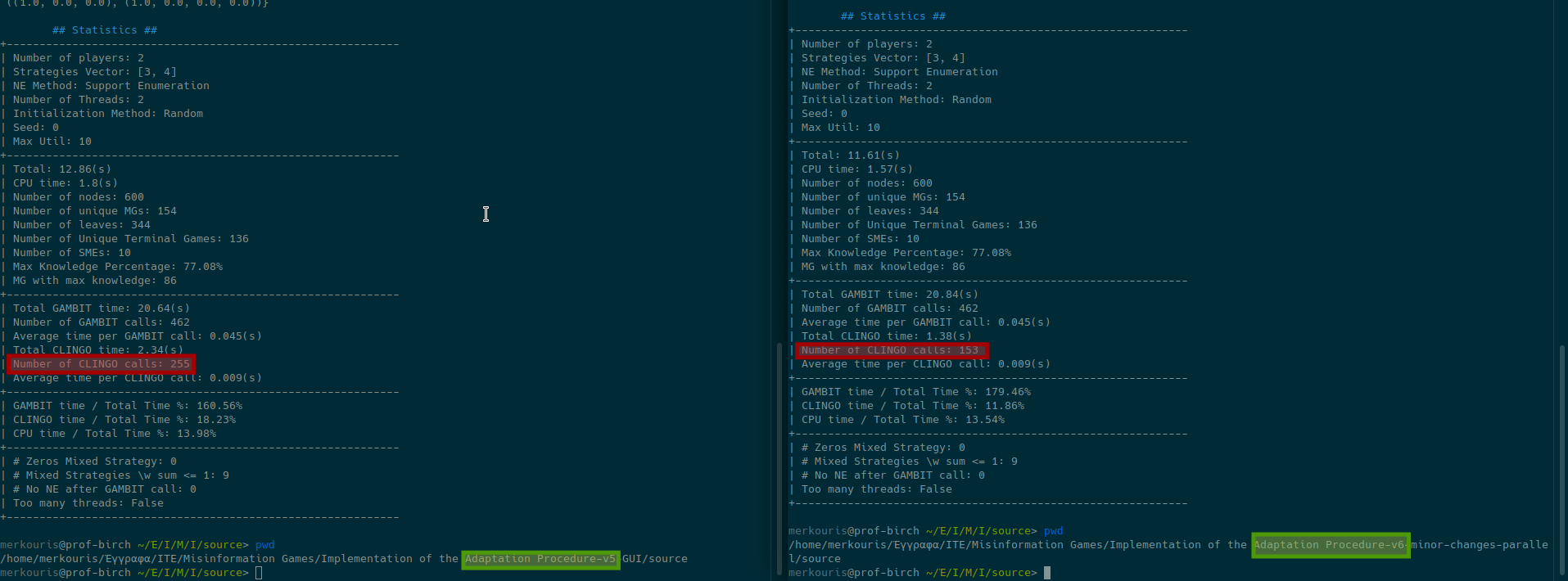

Before the adaptation procedure begins, but after the root misinformation game is initialized, we check exhaustively all the position vectors to test whether the update operation on the root misinformation game, at the position vector, results in a changed misinformation game. If not, we add this misinformation game ad hoc to the roots pos_vec_history. The disadvantage of this approach is that, in order to perform this test, we need to make an expensive CLINGO call for each position vector. Let a

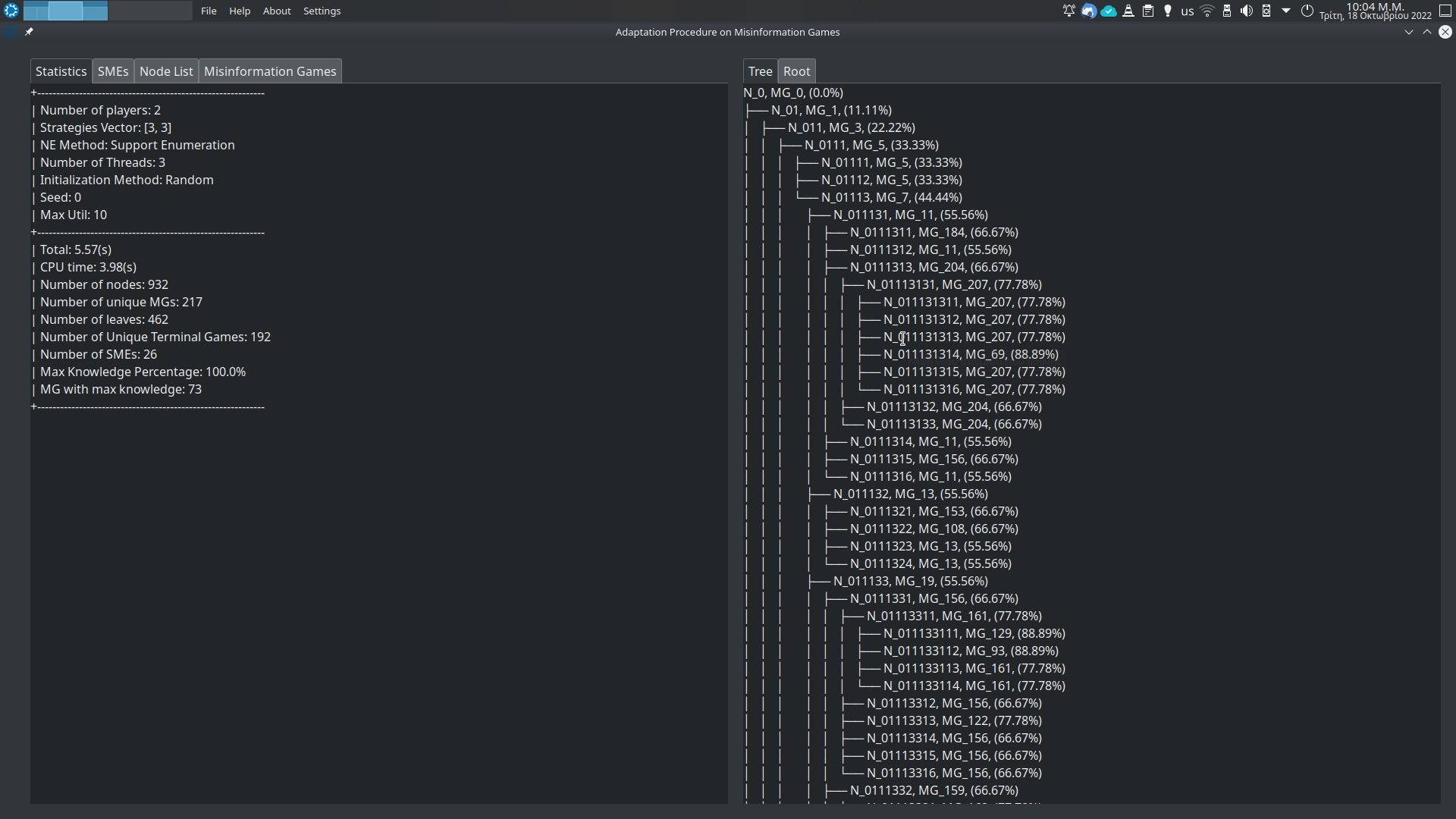

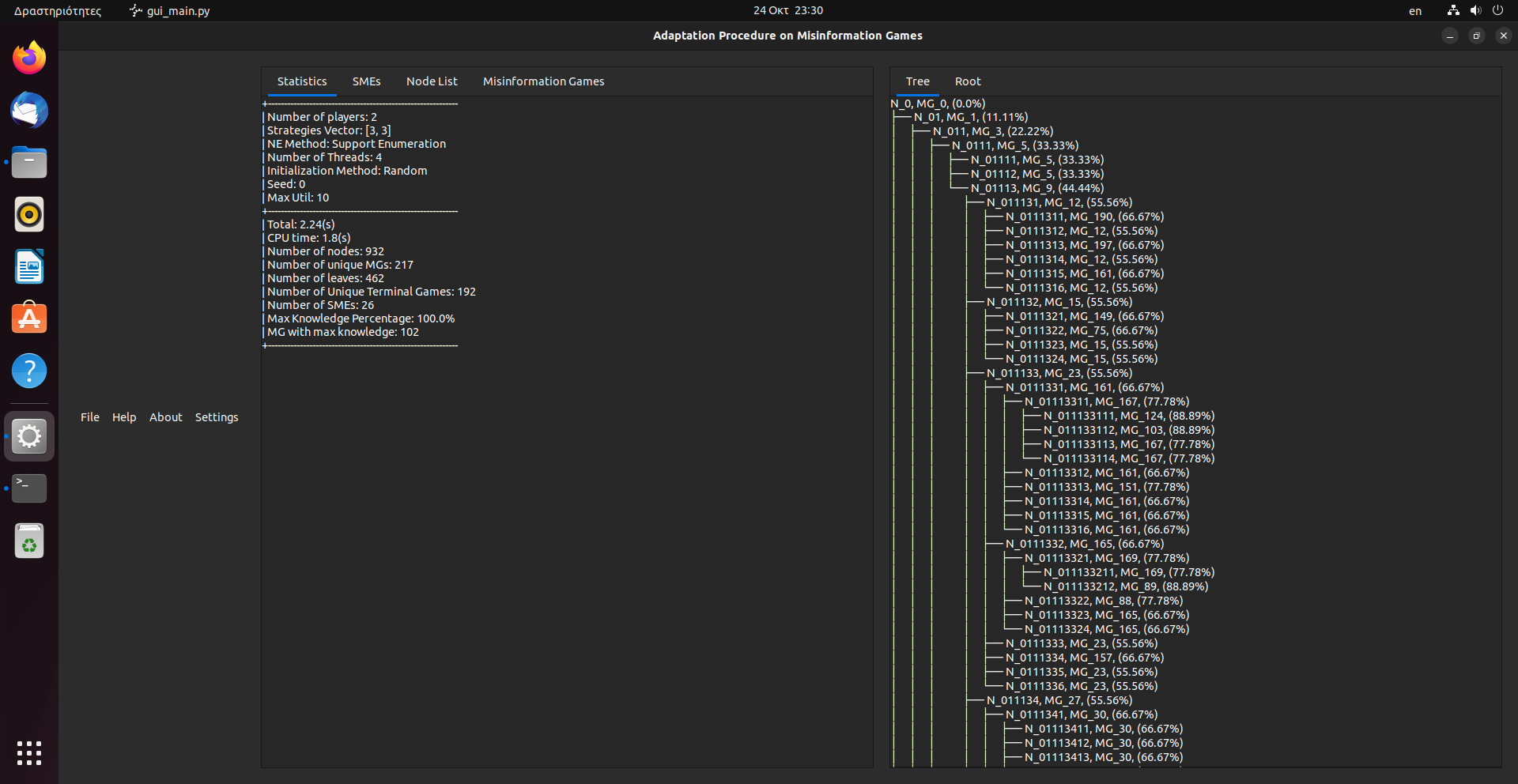

In the above figure, we see the execution of the same instance, without (on the left) and with (on the right) preprocessing. The instance we executed is python main.py -r 2 3 4 10 -fm -mtt 2 -dbg, namely an instance of a 2-player misinformation game, with player 1 having 3 strategies, while player 2 has 4 strategies. The maximum utility had been set to 10. The random number generator used the default seed 0. From the above discussion, the preprocessing costs

The utilitarian motivation for implementing a parallel approach1 is to make the expensive GAMBIT and CLINGO calls in parallel. Of course, our aim is for a fully parallelized approach, in order to take advantage of all the available resources of the machine. In other words, if k cores are available, we would like to make k GAMBIT calls in parallel. In this direction, we set the following goals.

- Independent Execution Each thread should be able to execute its

while-loopindependently of the other. - No Duplicate Computations. One thread should not make computations that another thread is currently making.

- No Waiting. No thread should wait the other.

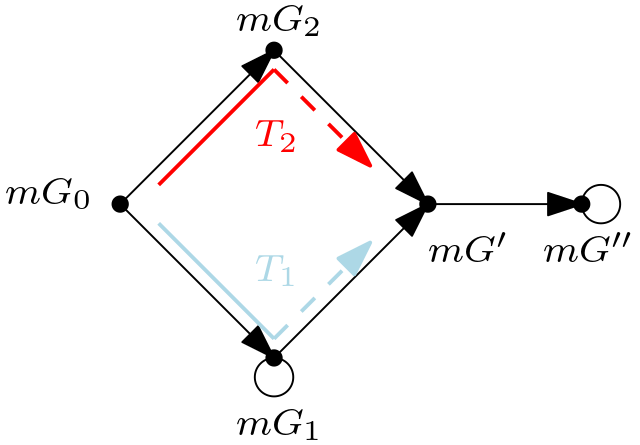

Observe that there is a trade of between (1) and (2, 3) of the above goals. The main problem appears when two threads are trying to access the same node. In general, this could happen quite often, since we can have diamonds in our graph (see paper). Observe the following figure.

Assume that thread T1 reaches a node corresponding to the misinformation game T2 reaches a node corresponding to

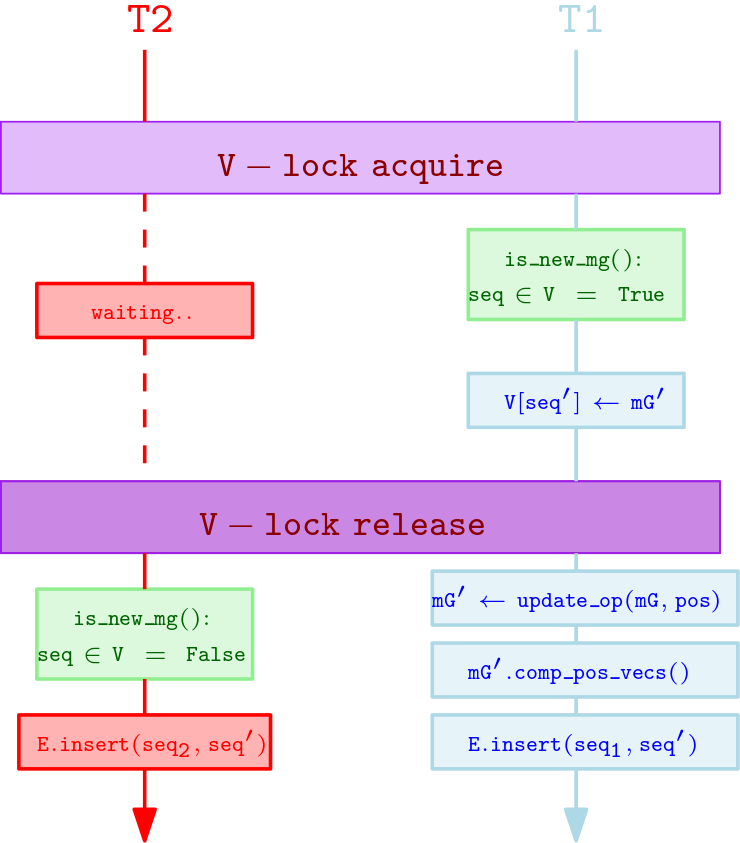

We assume that the two threads work independently (see 1st goal). If we allow the two threads to be completely oblivious of the computations of the other, then the expensive V is protected by a lock (mutex). Also, assume that the tread T1 succeeds to acquire the lock first. This way, T1 will execute the if part of the if-then-else block, while thread T2 will find that else part of the block. Therefore, we achieve the 2nd goal, i.e. T2 will not make computations performed by T1. On the other hand, if T1 releases the lock after completing the computations inside the if block, T2 will spend valuable time waiting T1 performing the expensive CLINGO and GAMBIT calls. Thus, the 3rd goal would have been violated. In our implementation we achieve all 3 of the goals we set.

We present our solution in the following figure.

In the above example, we assume T1 acquires the lock first. We allow T1 to keep the lock only as long it takes to check if the sequence is already computed. If the sequence corresponds to a new misinformation game, then we just create an empty instance of a misinformation game node and store it pointer to the dictionary. Then, T1 releases the lock. Now, T2 access the share dictionary V and finds that the key seq already exists. Hence, the is_new_mg() check will fail, and the else block will be executed, just adding the appropriate edge. On the other hand, T1 will continue its computations in parallel, computing the payoff matrices of the new misinformation game

Perhaps it is obvious why this parallel method wouldn't work for the slow mode. In the slow mode T2, after inserting the correct edge, would continue to access the children of T2 wouldn't be able to access the children of T1. On the other hand, the slow mode exists in our program for "historic" purposes and shouldn't be used, since it makes unnecessary computations.

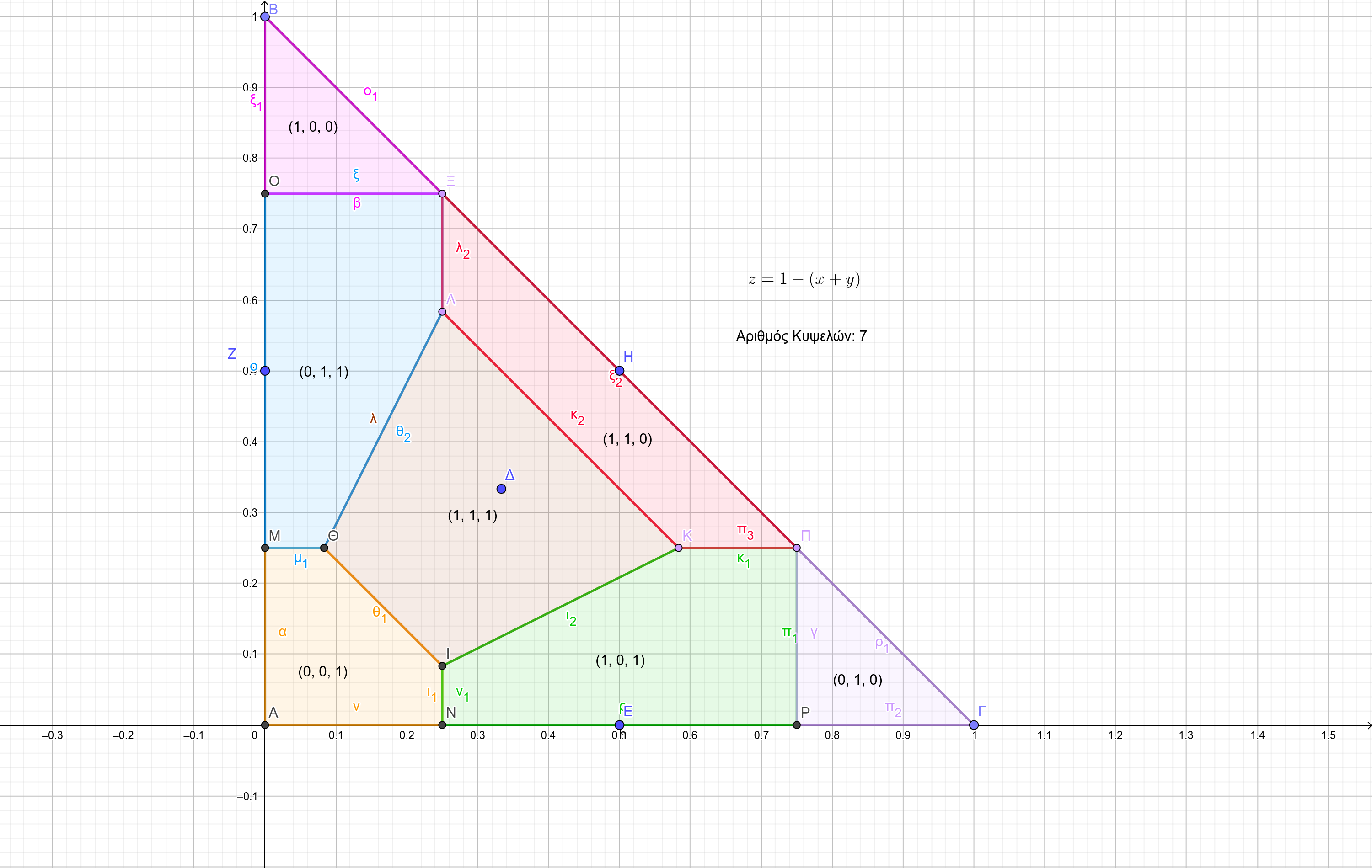

Another issue one (inevitably) faces when using real number arithmetic in computers is the truncation or rounding error. For example, how can we be sure that the strategy profiles ((0.001, 0.999), (0, 1)), ((0, 1), (0, 1)) are indeed two different Nash equilibria and not the same equilibrium printed twice, due to rounding errors. Unless we solve the misinformation game by hand it is quite difficult to reach a definite conclusion. Nevertheless, we provide some tools that can be utilized by the computer scientist or user, in order to control such errors.The AdaptationProcedure class takes as argument an instance of the SPDomain class located in file domain.py. This instance is then passed as argument to the constructor of the MisinformationGame and NormalFormGame classes. Essentially, the SPDomain class encodes a mapping from the GAMBIT's results to a user defined domain. Essentially, we could choose any mapping preserving the strategy properties of the strategy profile.

Observe the following figure.

Remember that if

From each equivalence class, we can choose a "good" representative

We can use the above functionality by adding the argument -dmn <method> to our terminal command. The supported methods are the following:

-

-dmn vVoronoi. Where the method described above is used. -

-dmn rReal. Where the mapping$\phi()$ is the identical function, i.e. no change is made to the GAMBITs output. -

-dmn d <number of digits>Where the user can define the rate of accuracy by designating the number of decimal digits.

Note: When the -dmn d <number of digits> is used the SPDomain class is bypassed. The computation gets restricted to floating point numbers of d decimal digits by the GAMBIT subsystem. All the GAMBIT commands take as argument the number of decimal digits, hence we pass this argument directly to GAMBIT. Note that this restriction isn't enforced by truncation; on the other hand, GAMBIT returns mixed strategy vectors that respect the mixed strategy property defined above, i.e. the coordinates sum up to one. For example, let (0.5714, 0.0, 0.4286) be a mixed strategy returned by GAMBIT using 4 decimal digits1. When we make the same call using 2 digits, the strategy profile returned would be (0.57, 0.0, 0.43), where of course 0.57 + 0.43 = 1 = 0.5714 + 0.4286.

Unfortunately, despite the elegant theory behind the Voronoi method, we didn't observe any measurable improvement in performance or accuracy using this method. We suggest using the simple -dmn d <number of digits>, with fewer decimal points if it seems that rounding errors exist. Perhaps more research is needed for the Voronoi method to surpass the traditional approaches.