I like modbus. I like its concept and simplicity. I like the wired connection. I don't feel radiophobia, I just trust the wires more. I like decentralized and simple solutions. I understand that you can argue on every point.

Each input and output, the direction of movement of the signal, the intermediate state, remote control - everything can be controlled through a specific register. Application logic of the work provides the tools. Configuration via registers - interaction of tools.

An end-user device that can control the zones and scenarios assigned to it, regardless of the presence of external control. It looks like I invented a PLC.

- Turn off the lighting with remote control

- Pass-through switch on the button without a lock

- One button for N lighting channels

- Motion sensor that activates dim lighting

- The motion sensor can be remotely muted (for example, according to the daylight schedule)

- The motion sensor can be read remotely even if it is muted (a record of someone passing at a certain time)

- Master switch implemented physically

- Master switch activated remotely

- Overlapping lighting zones (one sensor can illuminate several different zones)

- Direct PWM control

- Remote control in all scenarios (e.g. Home Assistant)

Wiring topology. The wiring should be made in the form of beams from the switch cabinet to wall switches and lamps.

In this implementation, we have only 8 pieces each. Inputs, outputs, zones, scenes, gestures. You will have to install several devices on a house of 100m2.

- The input and output of the signal correspond to the specific pins of the arduino.

- The level of illumination. To simplify it, 4 levels are accepted. Off, On and two intermediate ones for working with pwm.

- The processor of the zone. A block that controls the behavior of one "zone" of lighting. It takes into account all incoming signals, change the state it if necessary.

- Gesture. A certain sequence of input signals that matches the specified ones. One click. Double. Triple. A long click. Hold. Click+Hold. When performing a gesture, a scene can be activated.

- Scene. A predefined set of zones or outputs.

- Action. The action is applied to the scene. One scene can be executed with different actions. Enabling. Shutdown. Switching. Rotation.

The diagram shows the logic blocks, the direction of movement of the signal and the registers that control them.

The operation scenario is configured by setting the values in the appropriate registers. Most settings look like a bit mask, where each bit corresponds to the output channel.

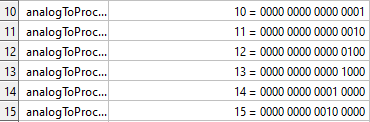

The simplest use case is the end-to-end transmission of the signal from the input to the output. This mapping looks like a ladder in bitwise form.

Tip

In the screenshot ModbusPoll software. I recommend using it when setting up and monitoring. The files in the mbp session are attached to the repository. Double-clicking on the register will open the register setup window. It will be possible to set the value bitwise.

We set the following registers to the specified values:

10 = 1; 11 = 2; 12 = 4; 13 = 8; 14 = 16; 15 = 32; 16 = 64; 17 = 128

20 = 1; 21 = 2; 22 = 4; 23 = 8; 24 = 16; 25 = 32; 26 = 64; 27 = 128

Registers 10-17 indicate that each analog input sends a signal to the corresponding processor of the zone. Registers 20-27 indicate that each processor sends a signal to the corresponding output. In the bit representation, we will see the same ladder. After that, the signal will pass freely from input 1 to output 1. From input 2 to output 2 and so on.

Let's change the value:

10 = 255

In bitwise representation, it looks like 1111_1111. We read it as follows: Analog input 1 sends a signal to all 8 processors. Since we previously assigned each processor its own output, it turns out that the first input will control all outputs simultaneously. Let's call it a master switch.

The register contains 16 bits. In the range of 10-17, the highest byte reflects the effect of the input on the zone processor as a sensor. The sensor will turn on the light in the minimum glow mode. Imagine that we have a motion sensor in the entrance area connected to the 2nd input. Let's set the register value:

it was

11 = 2 (0000_0000_0000_0010)

change to

11 = 1282 (0000_0101_0000_0010)

^ ^

Thus, we say that input 2 will illuminate the second zone by 100% and the 1st, 3nd zone by 50%. We have highlighted the adjacent areas.

We continue to work with the previous configuration. Let's say we have pass-through switches at inputs 3 and 4 that need to control the lighting at output 8.

12 = 128 (1000_0000)

13 = 128 (1000_0000)

But this option will require additional clicks on the switches to bring them to the same state. It's not very convenient. There are gestures for this. Turning off direct control:

12 = 0 (0000_0000)

13 = 0 (0000_0000)

Analog inputs 3 and 4 refer to gesture No. 1:

32 = 1 (0000_0001)

33 = 1 (0000_0001)

We add a gesture (one of eight possible ones) and a scene.

40 = 268 (0000_0001_0000_1100)

^^^ Action::Toggle = 4

^ apply to processor

^ no rotation

^^^ Gesture::OneClick = 0

^^^^ ^^^^ map to scene 1

50 = 32896 (1000_0000_1000_0000)

^ ^

apply to ch8 ^

activate ch8

After that, inputs 3 and 4 activate scene 1 by clicking and apply the Toggle action to it

Register No. 0 is the control register. You can write the command number into it and if it is executed successfully, the register will take the value 1.

All the settings above were performed with registers that are stored in RAM. To avoid losing the settings, you need to save the registers in the eeprom. This can be done by writing the value 734 to register No. 0. After that, when starting the arduino, the saved configuration will be automatically loaded.

By writing the value 2 to register No. 0, you can return the default settings.

Another configuration option is to modify the code LoadConfigDefaults. This is not so convenient as it will require rewriting the sketch after each edit.

Register 8 is responsible for the device number slave. Register 9 determines the transfer rate. The default Id is 1, 19200. After changing the values, you need to save the settings to eeprom and restart arduino.

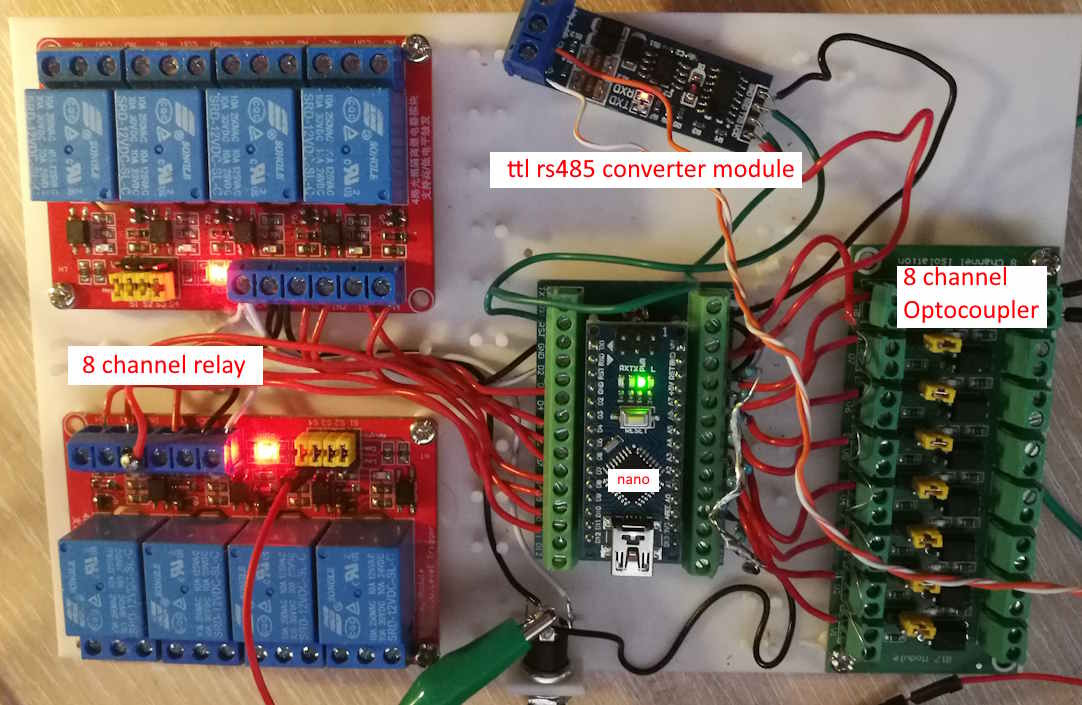

It was tested only on the Arduino Nano, but there is confidence that it will run on other models. Together with the modbus library, the sketch takes up 8398 bytes (27%). There is a margin for any RGB lib for example.

The modbus library used is: https://github.com/EngDial/ModbusTCP . There is no hard link to this option. You can replace it with any other one. It is important to leave the design framed around the poll call. If you have any ideas on how to push registers without memcpy, suggest it.

uint16_t data[registers_count];

memcpy(data, regs, sizeof(uint16_t)*registers_count);

_anyPollingMethod_( data, registers_count );

memcpy(regs, data, sizeof(uint16_t)*registers_count);

The BlinkBus class accepts one argument - this is a pointer to BBHardwareIO. An abstraction that reads and writes arduino pins. You can make your own implementation without getting into the main code. channel in the method signature takes values from 0 to 7. An example of the implementation can be viewed in BasicHardwareIO.

class BBHardwareIO {

public:

virtual bool ReadInput(uint8_t channel) = 0;

virtual void WriteOutput(uint8_t channel, bool trigger, LightValue lv, uint8_t pwmLevel) = 0;

};

BasicHardwareIO hardwareIO;

BlinkBus facade(&hardwareIO);

The inputs, outputs are decoupled via optocouplers. The ADCs are pulled down to the ground. Example connecting a single input and output:

The inputs, outputs are decoupled via optocouplers. The ADCs are pulled down to the ground. Example connecting a single input and output:

The RS485 level converter is connected to pins D0, D1 (tx, rx)