This project produces an interactive, national scale, choropleth map using Hydrologic Resource Units (HRUs) as data groupings. A HRU is the smallest spatial unit of the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) which is widely used to relate farm management practices to effects on surface waters at the watershed scale. The HRU is not generally defined by physically meaningful boundaries but instead lumps similar land uses, soils, and slopes within a sub-basin based upon user-defined thresholds.

This project plots the boundaries of HRUs and colors the interior of each HRU based on calculated water data availability values using JavaScript, the Vue framework, and Mapbox-gl to produce a 'zoomable' national level map.

Clone the project. Then run 'npm install' to pull down the required dependencies into the node modules folder

npm install

Starting the Vue development server at this point will show a website with headers and footers but no map.

npm run serve

There is a file in the project called mapStyles.js (src/mapStyles/mapStyles.js). This is a configuration file for Mapbox and it tells Mapbox a bunch of important details about how to create the map. What is important to us at the moment are two things, the 'source' and the 'source-layer.' The 'source' is where Mapbox should look for the 'tiles.' The 'source-layer' is only important to vector tile sources, so for something like pure GeoJson you will not need it, but since our tiles are vector we will need to make sure our source layer is correct.

The mapStyles.js is really just a ES6 JSON object called 'style', so like all JSON objects it is made up of key/value pairs. Of main concern is the 'sources' key. In the following example, we can see that there are two sources for our map layers. one called 'basemap' and another called 'HRU.' Mapbox needs two bits of information to process the source correctly, the 'type' and the location. Mapbox can process many different source types, the source we are using are vector, meaning mathematical created lines rather than dot graphed. Our vector tiles are stored in Amazon Web Services (AWS) and we have to tell that to Mapbox. What is important here is to know that our 'tiles' on AWS are in 'protobuf' format (.pbf). Protobuf is one of several tile formats that Mapbox can use. To load a '.pbf' source, we need the "tiles" key along with the resource location in the form of an array as shown below

style: {

version: 8,

sources: {

basemap: {

type: "vector",

"tiles": ["https://d38anyyapxci3p.cloudfront.net/baseTiles_3/{z}/{x}/{y}.pbf"]

},

HRU: {

type: "vector",

"tiles": ["https://d38anyyapxci3p.cloudfront.net/tileTemp_3/{z}/{x}/{y}.pbf"]

}

},

- the tiles are located in a different location on S3 (the above are just sample locations)

- you do not have the right 'source-layer' name

So, about sources and layers. Each source can be the parent of many map layers. Remember, that in the sample above, we had two sources. That does not mean that we have only two layers. Each source can hold the information needed to make many layers. In our map, we do just that. And we let Mapbox know which layers to make from each source by adding that information into the Mapbox configuration file, which, as mentioned previously, is called mapStyles.js in our project.

{

id: "HRUS Fill Colors",

type: "fill",

source: "HRU",

"source-layer": "no_simp_prec5", // make sure this name is right

"layout": {

"visibility": "visible"

},

paint: {

"fill-color": {

"property": "SoilMoisture",

"type": 'categorical',

"stops": [

["","#000000"],

["very low","#CC4C02"],

["low", "#EDAA5F"],

["average","#FED98E"],

["high","#A7B9D7"],

["very high","#144873"],

]

},

"fill-opacity": 1

},

"showButton": true

},

Above, is a sample of that shows how a map layer is defined. The detail that is important here is to note the 'source-layer' key. This has to match the name of the 'source-layer' in the tiles, and the name is defined by the person creating the tiles. So, it sometimes changes. If you find that a layer is not showing as expected, check that the 'source-layer' has the correct name.

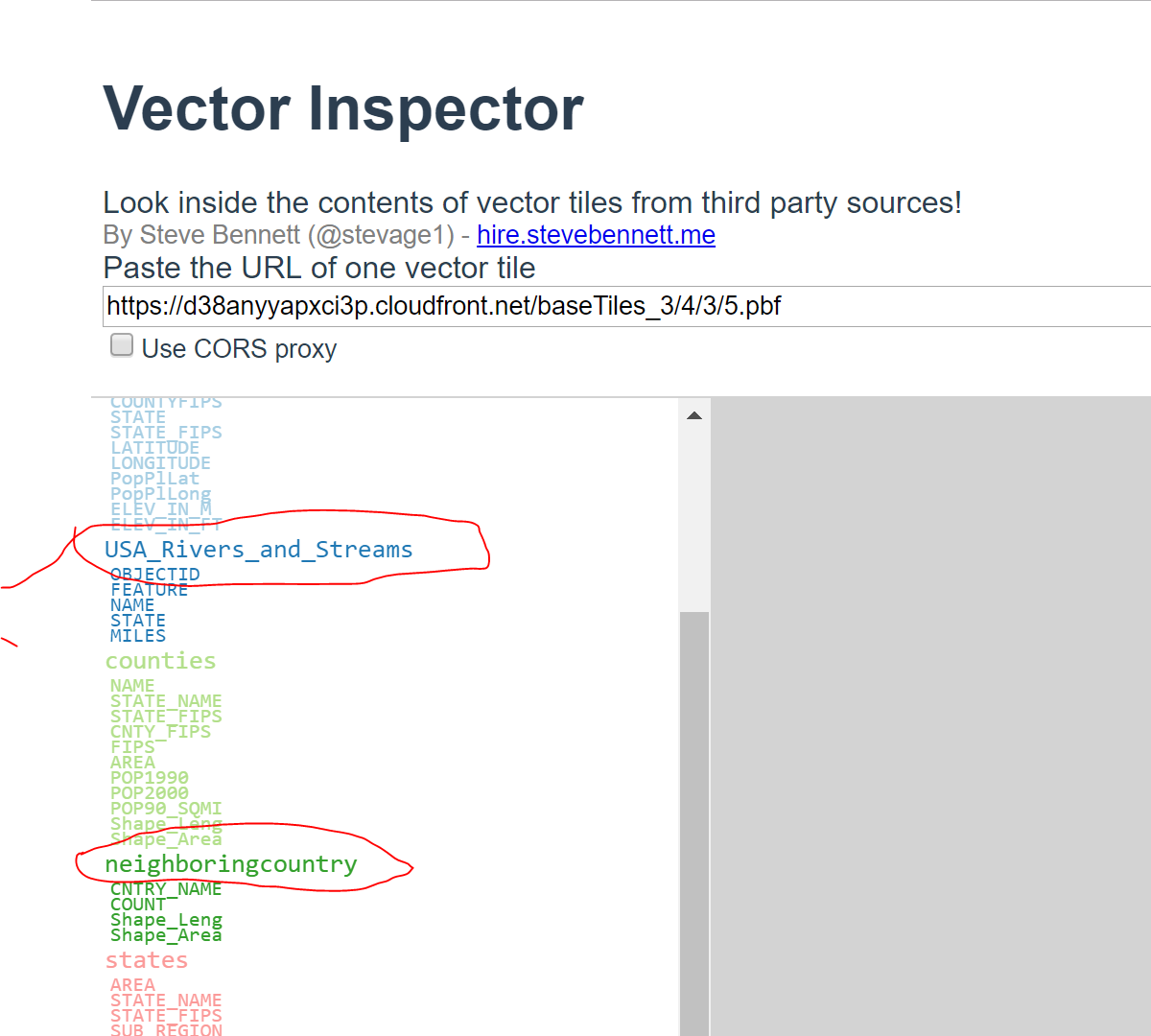

How do you know the name of the 'source-layer?' Well, it is not totally straight-forward. A way that works is to use a handy

program called, Vector Inspector https://stevage.github.io/vector-inspector/ . 'Vector Inspector' will give the name of

the 'source-layer' as shown circled in the image below.

Ypu may have asked yourself the question, can I run a set of tiles that I have on my local machine, or do I have to grab the tiles from AWS S3? The answer to your question is YES! You can run tiles from your local machine. However, you need to know that the environment on your local machine is different from that on AWS. There are two important differences:

First, on AWS, the tiles are stored in a Simple Storage Service (S3) 'bucket.' We have told AWS to 'serve' the contents of that bucket so that they may be used as a website. This is possible because AWS uses a simple web (HTTP) server to deliver the contents of the bucket to a web browser. On your local machine, the Vue framework provides a development server that delivers the content to a browser.

Second, since AWS is a web resource, all the content on AWS has a URL.

These two things combine to influence the way tiles are served runs in each environment. First, as we discuss in a moment, Mapbox-gl requires map tiles to be identified by as a web resource. That means it needs the tiles to have a URL in order to use them. This is fine on AWS, as all the resources have URLs, however locally this will require us to use a tile server to generate a URL from which Mapbox-gl can fetch the tiles. Secondly, while all the resources on AWS have URLs, AWS provides only a simple HTTP server to get those assets. Locally, our tile server(s) will do just a bit more. The local tile server will take a single '.mbtiles' tile file, break it apart, and serve each part as an individual tile.

Now, we could have added a tile server to our application when deployed on AWS, but we wanted to keep our application deployment simple (and inexpensive). Application deployments in AWS can use a S3 bucket as a source, only if they are static. And by 'static' I mean they are applications that run on a user's browser with the browser doing all the processing, and there is no need for server-side-processing. Adding a tile server would mean we have added server-side-processing and we would no longer be able to use S3 as our host; we would have needed to switch to a more complex and expensive Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) instance.

To avoid jumping up in cost and complexity to EC2, we compensated for the AWS HTTP server's inability to clip up '.mbtiles' files by doing that part ourselves. So, on AWS we store the map tiles not as a single '.mbtiles' file but as a folder of folders, with each folder containing sets of '.pbf' files that represent map 'zoom' level. Since we have manually done the tile cutting, the simple HTTP server on AWS can do the rest.

Why is this important:

- on AWS, the the map tiles are 'cut' into '.pbf' files.

- on your local machine, you will have a single '.mbtiles' file (you may have several of these, but the each represent a single map layer)

- on AWS, the simple HTTP server will deliver the tile files

- on your local machine, you will need to start a tile server for each '.mbtiles' file

- on your local machine you can serve '.pbf' tiles by running a local HTTP too

Locally, the tiles for the map will be served by 'tile servers.' These servers will need to know where the tiles are stored on your machine and will produce a URL that Mapbox-gl can call. When Mapbox-gl calls, the tile server will serve up the appropriate tiles.

Please note that Mapbox-gl requires the map tiles to have a full URL, for example 'http://localhost:8086/data/basemap.json.' or 'wbeep-test-website.s3-website-us-west-2.amazonaws.com.' This is works fine for web based resources but makes using a relative path impossible, which means that Mapbox-gl will require you to have a different URL for every deployment option. The path Mapbox-gl uses are found in the style variable of the component creating the map element, such as 'MapBox.vue.'

let style = {

version: 8,

sources: {

basemap: {

type: "vector",

url: "http://localhost:8086/data/basemap.json" // here is one URL

},

HRU: {

type: "vector",

url: "http://localhost:8085/data/new2.json", // here is another

In the above example there are two URLs, one for the base map and a second one for the HRUs. Notice that these are both local URLs. These URLs may differ slightly from what is required on your local machine. The main change would be the file names, which in the example are 'basemap.json' and 'new2.json.' These file names need to match the names of the tile files (except the ending will be '.json' and not '.mbtiles'), which we will talk about later.

Now, since there are two URLs, we will need two tile servers, one to produce each URL. A perfectly good choice for a tile server is tileserver-gl-light: https://www.npmjs.com/package/tileserver-gl-light . It is available as a npm package. Follow the instructions on the tilesserver-gl-light page and install the tile server globally (use the -g flag).

Now that you have a tile server installed locally, you can get the map up and running in the application. The tileserver will need two items of information, the location of the tiles, and the port address on which to run.

tileserver-gl-light basemap.mbtiles -p 8086

The above example works when starting the tile server from directory containing the tile file to be used. In this case, the tile file is named 'basemap.mbtiles. That is just an example name. The exact name may be different.

Using port 8086 is an arbitrary choice, but since the Vue development server is usually running on port 8080 this keeps conflicts to a minimum. Also, the port number must match the port listed in the URL of the 'style' variable, as shown in the code snippet a few sections above and directly below.

url: "http://localhost:8086/data/basemap.json"

// the server for the base maps must use port 8086 or at least match what is in the URL

Just as side note, notice that the file name in the above command matches the name of the tile file not the name in the in the style variable URL. The reference in the URL is to the file created by the tile server.

One you have the tile servers and the Vue Development server running you are ready to check out the application complete with map. Enjoy!

The AWS CLI is powerful tool that allow us to bypass some of the limitations of the Amazon Web Services User Interface.

Unfortunately there is no way to download the contents of an entire directory from S3 using the graphic

user interface, arrgh. So to get the tile files you will have to install AWS-CLI. This is accomplished by

using 'pip.'

// this is an example, it is highly recommend that you do an internet search

// for the most recent install information

sudo pip install awscli

Installing AWS-CLI is the easy part, now you have to configure the credentials. First, you have to get the credentials. For obvious reasons, I can not give too much detail here, and you will have to contact a team member for more specific advice. However, once you have the credentials you will run . . .

aws configure

This will start a program that will ask you to enter four items:

- AWS Access Key ID

- AWS Secret Access Key

- Default region name

- Default output format

The answers you enter will be saved at ~/.aws/credentials on Linux, macOS, or Unix, or at C:\Users\USERNAME.aws\credentials on Windows. I am not sure if it best practice, but I have edited this file manually without problems.

If you open the '.aws' directory you will find two text files: 'credentials,' and 'config.' The 'config' contains the answers to the last two questions and the name of the profile.

// example of 'config'

[default] // this is the profile

region = '' // this is the location of the AWS server like 'us-west-2'

output = json // this seems fine

When opened in a text editor, the credentials file looks something like this:

[default] // again, this is the profile

aws_access_key_id = the key id you added

aws_secret_access_key = the key you added

Once that is all set up, you are good to go. The AWS-CLI will find the credentials, and you will not be prompted to enter them when you run commands such as . . .

// General example to copy directory from S3 to current working directory

aws s3 cp s3://mybucket . --recursive

// Specific Example for grabbing '.mbtiles' and placing them in the current working directory

// We have been using the 'tiles' directory at the project root

aws s3 cp s3://prod-owi-resources/resources/Application/wbeep/tiles_current . --recursive

If you ever need to manually upload tiles to AWS, this command works provided you have installed AWS-CLI on your machine and that you have configured the credentials.

// generic example

aws s3 cp <local directory> <s3 target bucket> --recursive --content-encoding 'gzip' --content-type 'application/gzip'

// Note: using the 'content-type' application/x-protobuf also seems to work, and may be the better choice

// Here a specific example

aws s3 cp . s3://wbeep-qa-website/tiles --recursive --content-encoding 'gzip' --content-type 'application/x-protobuf'

If you do not configure the file compression correctly, when the application is run, Mapbox-gl will not be able to read the tiles, leaving you with a map-less web page and a cryptic error in the console.

Unimplemented type: 3

This means that everything is working except that the compression type is not what Mapbox can use. The tiles will have to be reloaded to AWS with the correct content-type and content-encoding.

A note on content type: Using '--content-type 'application/gzip' such as in this example, aws s3 cp . s3://wbeep-qa-website/tiles --recursive --content-encoding 'gzip' --content-type 'application/gzip', will work in some browsers. We found that Chrome has no problem using this encoding. However, it will cause the 'Unimplemented type: 3' error, as mentioned above, when using Firefox.

A second option, which avoids the hassle of configuring the AWS-CLI credential is to use the AWS UI to upload the files. Here you can drag and drop the files for uploading, just make sure to set both the 'content-encoding' and the 'content-type.' The content-encoding will be 'gzip', and the content-type will be application/x-protobuf Note that there is not a specific item in the drop down menu for these choices, but they can be added in the text box.

The project includes Docker and Jenkins files as well as a build shell script to support automated building of the Vue app via Jenkins (tiles are built in a separate process).

The build process will remove all existing files from the targeted S3 bucket except for the tiles directories and their contents.

A variety of build scenarios are supported via build parameters in Jenkins:

- The BUILD_DEST parameter has four options, 'test', 'qa', 'beta', and 'prod' Each of these choices correspond to one of our four S3 buckets and indicate the where the Jenkins build job will deliver the build version of the project.

- The VUE_BUILD_MODE parameter has two options, 'development' and 'production', this option tells the Vue application which environment variables to use. There are several feature differences between the 'development' and 'production' versions of the application that are controlled by these variables. However, the main significance here, is that the variables control which of our S3 buckets 'test' or 'prod' from which the map will grab the tiles.

- Combining the two options above in different ways allows either version of the application to be served from any of the various tiers. The main use of this would be to build the production version of the application to the 'test' deployment tier, which would allow us to pull the 'production' version of the tiles to the map on the 'test' tier.

- The last parameter is the BRANCH_TAG, this is used in versioning. The most common choice will be 'origin/master'. This will build the 'development' version of the application to the 'test' S3 bucket.

So you want some cool icons, but do not have time to make them yourself. This is where Font Awesome comes in. Font Awesome as a bunch of no free icons and also provides a Vue plugin to use them as mini Vue components.

To start we need to add three NPM packages to the project.

npm install --save @fortawesome/fontawesome-svg-core

npm install --save @fortawesome/free-solid-svg-icons

npm install --save @fortawesome/vue-fontawesome

Once these are installed, remember to stop and restart your Vue development server, if you had it running, so that it can pick up the changes.

Now turn your attention to 'main.js'. This is where we need to do our 'global' imports of NPM modules. If you did the 'makerspace-website-base' tutorial, you will recall that this is where we imported the United States Web Design System (USWDS). We can do our imports in any Vue component, but when we do the importing in 'main.js', we will have access to those imports in any Vue component in the project. Imports in other Vue components are only accessible from the component in which they were imported.

In 'main.js' we will first import the 'fontawesome' library. This will give us the 'library' object and allows us to 'add' icons to it.

import { library } from '@fortawesome/fontawesome-svg-core'

Next we will import the icon we want to use. Again we could do this in a specific Vue component, but doing it here will let us use the icon anywhere in the project.

import { faLayerGroup } from '@fortawesome/free-solid-svg-icons'

The icon we are using is called 'layer-group', which is the image of a set of stacked layers, and I found it by browsing the Font Awesome Gallery (https://fontawesome.com/icons?d=gallery). Now you may have noticed that I said the icon is called 'layer-group', but we are importing 'faLayerGroup'. You may also be asking yourself, 'what is up with that?' And if you are, that is a reasonable question. Honestly, I do not know the answer, but I can tell you how to find the information you need to make the icon names work in Vue.

Step one - find the icon you want to use in the gallery mentioned previously. Somewhere near the icon you want to use it will say something like . . .

<i class="fas fa-layer-group"></i>

In old fashioned HTML markup this is code is what we would use, but this is not the syntax we want to use to include the icon in Vue. However, we do want to make note of the name. In this case, 'fa-layer-group'. Notice how similar that is to both our import of 'faLayerGroup' and our icon name of 'layer-group'. Most of the time it is probably possible to guess the information we need from the 'class' information, however we can dig deeper to be sure.

Step two - find the icon in the 'node_modules' folder

So when we did our NPM installs, that process added a folder called '@fortawesome' (yes,'fort' not 'font') to the 'node-modules' folder. Inside this folder, there are (at least) three more folders, one for each of the NPM installs we did earlier. In the 'free-solid-svg-icons' folder we will find a bunch of TypeScript and JavaScript files. These files have names like 'faAddressBook.js' and 'faAddressBook.ts'. At this point, you may have caught on to the fact that these files have the same name (minus the file extension) as the one in our import statement 'import { faLayerGroup } from '@fortawesome/free-solid-svg-icons''

If you do not remember, here it is again . . .

import { faLayerGroup } from '@fortawesome/free-solid-svg-icons'

You can safely click on one of the '.js' files such as 'faLayerGroup.js'. When this file opens, you will see that it has information about the layer-group icon. Specifically (among other things), it says 'var iconName = 'layer-group';'. So we now know, definitively, the name of our icon, which we will use when we place the icon on the page. This also confirms that we have imported our icon from the correct '@fortawesome' subfolder, in this case 'free-solid-svg-icons'.

Alright, cool. We finally have this import stuff straightened away and can now move on to getting our little icon to work. Step one - activate the special powers of the 'vue-fontawesome' module we installed and then imported in previous steps. This module allows us to use the Font Awesome icons as 'mini' Vue components. To get this to work, we must first 'register' it as a Vue component and give it a name like so . . .

Vue.component('font-awesome-icon', FontAwesomeIcon)

This calls the Vue method to register the 'FontAwesomeIcon' model we imported and names it 'font-awesome-icon'. You can name it anything you like, but for consistency it is probably best to stick with 'font-awesome-icon'. This is name you will use later when the icon is added to our Vue template(s) as a Vue component--which in old HTML would have been called an 'element'.

Step two - add the icon to the 'library' object. Since we globally imported the FontAwesome 'library' object, we can now use it throughout the application. We can add our icon to the 'library' object with this code.

library.add(faLayerGroup)

Sweet! Our importing and registering work in 'main.js' is done for now. If we want to add other Font Awesome icons to our project later we just need to 1) import the specific icon from the 'node_modules' folder, and 2) add it to the 'library' object.

Now your 'main.js' should look something like . . .

import Vue from 'vue'

import App from './App.vue'

import uswds from 'uswds'

import { library } from '@fortawesome/fontawesome-svg-core'

import { faLayerGroup } from '@fortawesome/free-solid-svg-icons'

import { FontAwesomeIcon } from '@fortawesome/vue-fontawesome'

Vue.component('font-awesome-icon', FontAwesomeIcon)

library.add(faLayerGroup)

Vue.config.productionTip = false

Vue.use(uswds)

new Vue({

render: h => h(App),

}).$mount('#app')

That was the hard part. Now we can go about merrily stuffing our new icon anywhere we like in our Vue project. The process is this: 1) Go to the component where you would like to add the icon 2) In the 'template' element of that component add the icon as 'mini' Vue component like so . . .

<font-awesome-icon icon="layer-group" />

This is where the names we mentioned earlier come in to play. First, since we have registered 'font-awesome-icon' as an Vue component, we can use it as HTML tag to create a Document Object Model (DOM) element. To this element, called 'font-awesome-icon', we will add the attribute 'layer-group', which as was also mentioned earlier is the name of our icon. This tells Vue to stuff our 'layers-group' icon into the 'font-awesome-icon' element and display it on the web page. If we were to add other Font Awesome icons, we could add them to the page using the same 'font-awesome-icon' tag. The only change (assuming that you registered the new icons in 'main.js' (and I am sure you did)) is to change the name of the 'icon' attribute to that of the new icon. For example . . .

<font-awesome-icon icon="layer-group" /> <!-- this adds the 'layer-group' icon -->

<font-awesome-icon icon="coffee" /> <!-- this adds the 'coffee' icon (if you registered it in 'main.js)' -->

Pretty straightforward, right? Well . . . now that you know the pattern it is.

Update - Okay here is another odd twist. In the above discussion, we talked about adding FontAwesome icons from the 'free-solid-svg-icons' collection, and we basically worked out all the kinks in that process. However, there are other icons out in the wilds of FontAwesome land that are 'free' to use, but are not in the 'free-solid-svg-icons' package that we previously imported. A good example of these are the ones typically used for links to Facebook and Twitter. If you look in the 'free-solid-svg-icons' package, you won't find them, because they are in a different package called 'free-brands-svg-icons' that needs to be imported with NPM in a separate process.

npm i --save @fortawesome/free-brands-svg-icons

Once you have the package imported you can use the icons with the same steps as mentioned above, as far as going to 'main.js' and importing the individual icons and adding them to fontAwesome 'library' object. For example . . .

// Font Awesome-related initialization

import { library } from '@fortawesome/fontawesome-svg-core'

import { faFacebook, faTwitter } from '@fortawesome/free-brands-svg-icons' // this are your new icons

import { FontAwesomeIcon } from '@fortawesome/vue-fontawesome'

// Add the specific imported icons

library.add(faFacebook) // add them individually to the library object

library.add(faTwitter)

// Enable the FontAwesomeIcon component globally

Vue.component('font-awesome-icon', FontAwesomeIcon)

BUT! At this point things get weird. Previously, we would have gone to one of our components and added the icon in a pattern something like this:

<template>

<div class="icons">

<font-awesome-icon icon="twitter"/> // BUT!! Don't 'cause this will fail

<font-awesome-icon icon="facebook"/> // Same here, total FAIL

</div>

</template>

So if we attempt to add the icons way we did in the earlier section they will not work and you will get and error like . . .

[Error] Could not find one or more icon(s) (2)

{prefix: "fas", iconName: "twitter"}

{}

Okay, this is annoying, but as you may have surmised, it is caused by the icons coming from a different FontAwesome package than in the previous example. The error notes that it seeking an icon with the prefix 'fas'. The prefix 'fas' stands for 'Font Awesome Solid' which kinda makes sense for icons in the 'free-solid-svg-icons' package but not so much for those in 'free-brands-svg-icons'. But why is it looking for the prefix 'fas'? We never told it to do that! Well, apparently this is related to behind-the-scenes coding of the 'FontAwesomeIcon' component which, you may remember, we wired our imported icon to in the last step of our work in 'main,js'.

// Enable the FontAwesomeIcon component globally

Vue.component('font-awesome-icon', FontAwesomeIcon)

Inside the code of the FontAwesomeIcon component there is a section that basically defaults to the most common prefix, of 'fas', unless you specifically tell it to do otherwise. To keep things brief, here is the magic way to tell the FontAwesomeIcon component to use 'fab' rather than 'fas' ('fab' for Font Awesome Brands verses 'fas' for Font Awesome Solid). Note, you only need add the extra bit of JSON to icons outside of the 'fas' package, since the component creation code will default to 'fas' as the icon prefix.

<template>

<div class="icons">

<font-awesome-icon :icon="{ prefix: 'fab', iconName: 'twitter' }"/>

<font-awesome-icon :icon="{ prefix: 'fab', iconName: 'facebook' }"/>

</div>

</template>

Here is another interesting thing to know about using FontAwesome Icons as Vue components. When we wire up our icon as a Vue component, some more magic goes on in the background that adds style classes to the component. If you examine one of icons with a browser's development tools you will see the element looks something like . . .

<svg data-v-75bed3d5="" aria-hidden="true" focusable="false" data-prefix="fab" data-icon="twitter-square" role="img"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" viewBox="0 0 448 512" class="svg-inline--fa fa-twitter-square fa-w-14">

<path data-v-75bed3d5="" fill="currentColor"></path></svg>

In the above snippet, notice that there is a 'class' attribute with three assigned classes: 1) svg-inline--fa 2) fa-twitter-square, and 3) fa-w-14. These classes are added to the component during creation and we can target any of them with CSS styling code. These classes are basically 'secret' and don't show in the code; they are only visible with the developer tools in the browser. So it is important to know that they are there (in hiding) as other developers may have targeted these classes, leaving you to wonder what the heck is going on.

Thanks to the folks at BrowserStack for the use of cross browser quality assurance tools - BrowserStack