This workshop has been made for students of Founders and Coders, and therefore assumes that you have completed lesson 1 of Udacity's Git and GitHub course (as part of the precourse material)

All contributions to this workshop are very welcome! If you have any suggestions for improvements, please raise an issue. The author will let you know whether they prefer to make the changes themselves, or whether you are welcome to submit your own PR (Pull Request). If you do make PR yourself, please follow the Founders and Coders contributing guidelines.

- Getting Started

- Branching

- Making Changes

- Merging with Master

- Merge Conflicts

- Changing File Structure

Version control makes it possible for you and I to work on one file at the same time, because we can keep both our versions saved and then compare them once we have each finished our work. This allows us to integrate our changes more swiftly.

Most developers use git as their version control system, but different teams use different "workflows". At Founders and Coders, we generally follow something called "GitHub flow", because this flow makes it easy to deploy the latest version of your application very regularly. For a fuller explanation, there is a useful article in the resources section.

To see the steps involved in working on a "feature branch", follow GitHub's visual guide now.

What is a branch?

Creating your own "branch" is like taking a copy of master and renaming it. When you commit, the changes that you make will only exist on that branch. As you work on a GitHub repo, the first branch you are on is the default branch, called master. If you wanted to start working on a new section of the website (say the footer styling), it is best practise to create a new branch for working on that feature.

Next please fork this repository.

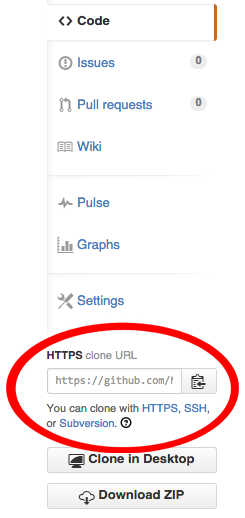

The next step is to clone the forked version of this repository. On the main page of the repo, copy the url shown here:

Then use the command in your terminal:

git clone https://github.com/NataliaLKB/learn-git-basics.git

You should now be able to redirect into the directory just created using the command line.

Next, it is good to get in the habit after each command to use git status. Let us use it now.

git status

Now check which branch you are on:

git branch

You should only see master which is the default branch in this repo.

When there are other branches in your repo the green branch is the current one you are on.

The next step is to create your own branch to work on. try this:

git branch new-branch

It is best to try to name your branches as specific as possible, so not to confuse them with any others. There are many naming conventions out there for branches, but for this week simply try to name them off of a feature. For example (navbar-collapse or sass-file-structure). To see all your branches:

git branch

As you can see, you have created your branch, but are not currently on it. To navigate onto it please:

git checkout new-branch

git branch

Now you can see you are on that branch. Go back to master and now we are going to delete new-branch.

git checkout master

git branch -d new-branch

git branch

As you can see, your branch is now gone.

Now it is time to make some changes in the project. Make yourself a new branch named update-cheatsheet and go onto it. open up the file cheatsheet.md in your favourite text editor.

As you can see, this contains all the commands you will need to begin using git. Continue to add to it all the new commands you learn. To begin, here is a command that both creates a branch, and moves you onto it at the same time:

git checkout -b <new branch name>

Add that command, and its description to cheatsheet.md and save it. Now in your terminal:

git status

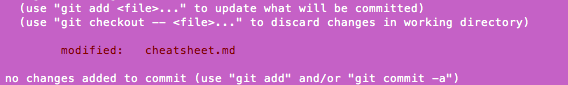

You will see something like this:

You will see your changes in red. now we need to add them to the git staging area. Doing this is like telling git to pay attention to these files, and start tracking the changes. To do this write this command:

git add cheatsheet.md

git status

Now you can see the file name has turned green. Now to commit your changes.

git commit -m 'adding new command in the cheatsheet'

git status

The message could be anything, but it is best to make it something that describes what you just did. You can also use the command git commit without -m '<message', however beware that it will send you to a text editor called Vim. Though learning how to use Vim is important, it isn't necessary at this stage. Typing :q straight away will get you out of it and commit again with a message.

Now that you have made and committed your changes, it is time to merge your branch with master. Even though you are not working with anyone else on this repository, it is always good practice to make sure your current branch is completely up to date with master. Imagine if you were working with a team. Someone else has already pushed up changes to master. If that someone else and yourself have changed the same file, it is quite likely that your changes will not be compatible with theirs. To avoid this, you want to merge your changes with theirs to avoid future problems. Checkout back onto master and pull down. These commands look like this:

git checkout master

git pull origin master

Pulling down means that you are getting any recent changes from the remote master branch which is located in Github. Next go back to your branch (update-cheatsheet) and merge with master.

git merge master

Even though in this situation there isn't any changes to merge, it is best to get in the habit on going through these steps in your work flow. Merging like this means taking any possible changes in master and merging them with the branch you are currently on. After you merge with master you have to push your changes to the remote repo (Github).

git push origin update-cheatsheet

When you pull or push you are referring to your remote repo, or origin. In the example of git push origin <branch name> you are pushing your local changes to a remote branch that you are both creating, and naming. Since you are creating this branch from your local one it makes things much simpler if you use the same name for your remote branch, as your local one.

For more information on pushing, see here

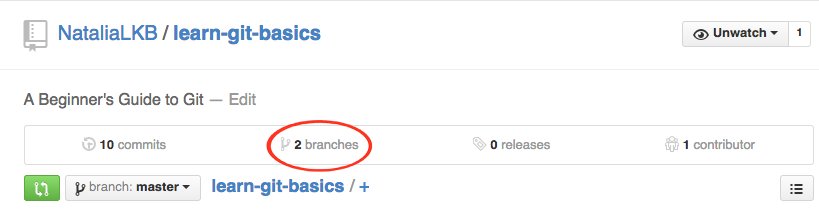

Go to your browser and open up this repository in github. Press the branches button

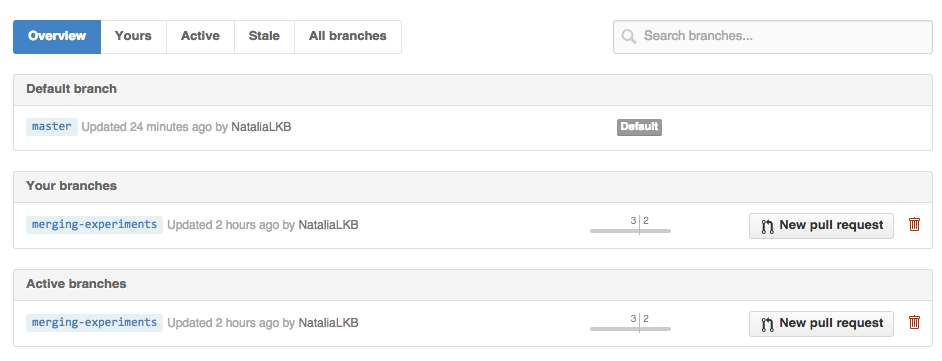

And then make a pull request to master

Afterwards you will see a merge button. Press it and delete your branch. Now your remote branch master is completely up to date with your latest changes.

Return to your terminal and navigate to your local master branch. Pull down. You will see your branch update (fast-forward). Delete the branch update-cheatsheet.

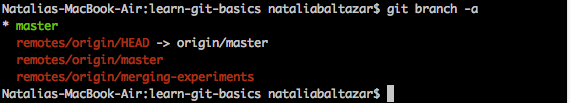

Check all the branches on this repository, even the remote ones. To do this use this command:

git branch -a

You should see something like this:

Run the command:

git checkout merging-experiments

Open up the git cheatsheet, as you can see there are some differences between this and master. To see these differences use command:

git diff master

The differences in green and the additions on this branch, that don't exist on master. The red are the things that are on master, that don't exist on this branch.

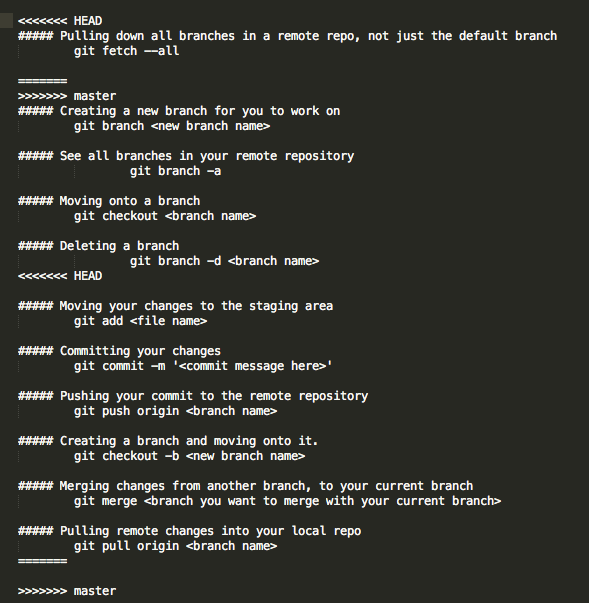

Merge with master. You should have a git conflict that looks something like this:

Do you see the lines at the top. The first section is labelled HEAD those are from this branch. The next section is from master. Delete the lines, and any other code you want until the cheatsheet looks like how you want it to look.

Afterwards git status, add the files in red, commit, and push. Then make a pull request to master like before and merge. Don't forget to update your local master branch, and delete the merged branch in Github and in your local repo. It is good to keep your working environments clean and organised.

Imagine you're working on a project that's getting bigger in size. As new files are added, it makes sense to group some of them into folders. For example, it's a good idea to keep all CSS files in one folder, JS files in another etc.

Let's assume you've just cloned a repository structured like this:

index.html

stylesheet.css

script.js

However, you'd prefer to split these into folders like:

css/stylesheet.css

js/script.js

index.html

In order to achieve this, git mv command comes in handy. Using it to move files ensures preserving history of the files you work on. To change file structure like above (and create new folders at the same time) use command:

mkdir css && git mv stylesheet.css ./css

mkdir js && git mv script.js ./js

(This glues mkdir and git mv commands together with && operator).

Basic function usage is

git mv <source> <destination>

The command also takes optional parameters. To find out more, refer to documentation.

Simply put, the HEAD is a reference to a commit object. For more information see: http://eagain.net/articles/git-for-computer-scientists/

As you know from the Udacity course, git stores all the commits on the project. You can use them as a timeline and travel back and forth in time. This section reminds you how to do that, which will come in handy as you work in projects with your team.

Make a new branch called timeline-practice and navigate onto it.

Step 1) Make a new directory in the project via the command line. Lets call it time.

mkdir time

Step 2) Also make a new file in that directory and call it whatever you like. A simple text file should be fine. After you are done, open it.

touch time/newfile.txt

open time/newfile.txt

Write the current time stamp, and a short message to your future self. Save it. Next add and commit your changes. Your commit message should be descriptive of what you just did. Repeat step 2 twice more, deleting the previous time and message, and adding the new time and a different message. Make sure you add and commit each time. Make sure your commit messages are unique, and you can tell which one was first, second, and third.

Step 3) Next type in this command:

git log

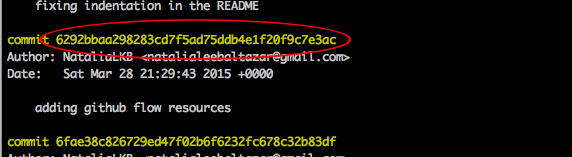

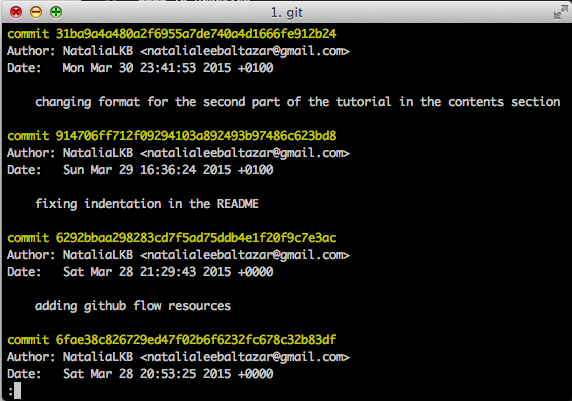

You should see something like this:

Pick the second time commit that you made and copy the hash. Use q to exit the log and checkout to your commit.

Step 4)

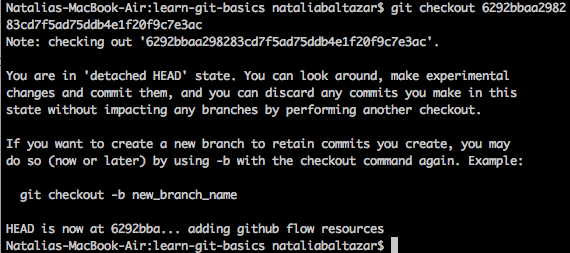

git checkout <commit hash>

git status

As you can see after you checkout a message appears informing you that you are in a 'detached HEAD' state, meaning your are not working on any current branch. Open up the file in the time folder and look at the time and message. It should be the 2nd one that you wrote.

Repeat step 4, and use the hash of the first time commit you made. Open the file and see that the time of your first commit, and your message to yourself. This is going back in time. You can easily go back as far as you like in the project and see older iterations of this tutorial!

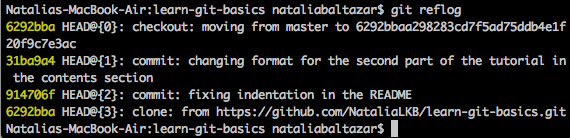

Next, we should go back to the future. The quickest and easiest way is to checkout onto thetimeline-practise branch and you should be back up to date. However, you can also navigate back to the latest commit from where you are now. First, check git log. You will notice your latest commits are no longer on there. This is where another command is handy. git reflog is best used to find recently "lost" commits. you should see something like:

Find the commit name of the last commit you did (the third time that you recorded) and copy the short hash in yellow. Checkout back to that commit, and git diff timeline-practise there should be no difference.

Checkout back to timeline-practise and push up to Github to make a pull request to master. Make sure you first check that

it is up to date with master locally.

You should aim each commit to be a "safe" version of the project. This means that if you checkout to any commit in your timeline, that should reflect where the project was at that point, and be functional.

Given that, when you commit is very important. I have heard two very useful guidelines.

The first, is that as you complete the task assigned to you, you make several commits at different times during that task. In the end you merge all those commits together to make one very informative commit of that task. I will talk about ways to merge commits together in a later section.

The second method is you work through your task and complete it before adding or committing at all. Then you check the status of the repo and see all the files you have changed. The next step is selectively adding and committing

Through my research I have come across many different methodologies, and ultimately you should try to do what seems the most natural to you. I use both of these methodologies depending on the extent of the task before me. The best thing is to always keep in mind that you and your colleagues will inevitably need to go back to your commits and it will help everyone if commits are aptly named.

Likewise, even in pull requests, you must aim to make your commits a clear and concise summary of what tasks where completed on that branch. That way the person reviewing your pull request understands what they will be reviewing before looking at the code itself.

Just like choosing when to commit, and what to commit, it is also important to think about your naming. It is always good to be as descriptive as possible with your commit messages.

Also consider:

- Present tense for your commit messages

- If related to an issue on github, should contain issue number

- The first line should be 50 characters or less. Your message should be brief and to the point.

- Focus on why you did something, not how you did it

- Avoid

ands. If you find yourself wanting to writeand, you should probably break up that commit into multiple ones.

Remember that the purpose of this commit is to be a message for future you, or your colleagues who may not have known what you are working on. Try to think about your message with this in mind.

Many development teams take it one step further and turn their commit messages into change logs. These change logs may be used for user consumption making it all the more important to have clear messages of what was done for that commit.

I tend to favour one line commits for simplicity, but many schools of thought out there prefer multiline commit messages. For examples of "best practice" formats for this see:

Often you will find yourself wanting to merge commits, or organising your early commits slightly differently on a branch to better demonstrate what you worked on. I will briefly go through one easy way to do this.

This is my preferred method of merging commits together. It leaves you with lots of flexibility.

To begin, make a new branch and make some new files and commit regularly (at least twice).

Next git log and pick the 3rd most recent hash. Copy it and:

git reset --soft <commit hash>

git status

git log

Your working directory shouldn't changes, but all the files that you changed should be in green. Your log should have the newest commit as the hash you copied. Even though all your work is still the same as before the reset, the commits are different. Then you can commit again and this is an easy way to replace 2 or more commits with one commit.

For more information and techiques see:

- What to learn more about reset?

- Only want to ammend the previous commit?

- The Golden Rule of Rebasing

Have you found a useful Git or GitHub resource or tutorial? Please let us know by creating an issue

- Why you GitHub flow? Read this article from a developer at GitHub: http://scottchacon.com/2011/08/31/github-flow.html

- For generating ssh keys https://help.github.com/articles/generating-ssh-keys/

- CodeSchool "Git Real" tutorial: http://gitreal.codeschool.com/

- Atlassian (makers of SourceTree) Git Tutorials: https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/

- Git Branching: https://github.com/pcottle/learnGitBranching

- Interactive tutorial: http://gitimmersion.com

- Build Podcast (intro to Git) Video: http://build-podcast.com/git/

- Git User Manual: https://www.kernel.org/pub/software/scm/git/docs/user-manual.html

- GitHub's Treasure Trove of Video Tutorials: https://www.youtube.com/user/GitHubGuides (channel) and specifically: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FyfwLX4HAxM

- The simple guide to git: http://rogerdudler.github.io/git-guide/

- Jeff Schomay's Git-Fu presentation: http://slides.com/jschomay/git-fu

- Git Pretty: http://justinhileman.info/article/git-pretty/ (anything visual makes learning git much easier...)

- Intermediate: http://www.raywenderlich.com/74258/git-tutorial-intermediate

- Visualize your Git with SourceTree: http://www.sourcetreeapp.com/