This lesson will give you practice with the workflow we will be using for the rest of the course and will give you some hands-on practice with important tools that you will need to be familiar with as a professional data scientist: the command line, git, GitHub, and Jupyter Notebook.

You will be able to:

- Make changes to a Jupyter Notebook and push it up to GitHub

- Perform basic computations in a Jupyter Notebook and store them in a variable

There are two types of lessons on Learn - readme's where you are mainly reading text or watching videos and perhaps executing a code block or two just to see what happens. For those lessons, you don't need to know any of what we're teaching below. All you need to do is to read them on Learn. Enjoy!

However, there are some lessons that require you to write code - projects and labs. Generally, labs are a little smaller and better specified, allowing you to practice a specific skill in isolation (like practicing throwing the ball up without hitting it to improve your tennis serve). Generally projects come towards the end of a section and are more open-ended, allowing you to bring together a range of different skills that you have learned (like playing a whole game of tennis - or at least practicing a complete serve).

It's easy to tell from a lessons title if it is a project, a lab or a readme. If the title ends with " - Lab", it's a lab. If the title starts with the word "Project", it's a project. If neither of those two things is true, it's a readme!

The process we're teaching you below is only required for labs and projects - not readme's

Before we get into data science and Jupyter Notebooks, we'll need to know a tiny bit about our command line. When conducting data science (or programming in general), it's important to get comfortable with the command line. On Mac computers, this is the terminal application. On Windows computers, we'll use "Git Bash". The command line serves as a low-level interpreter through which you, the user, can send commands directly to the computer. As a computer user, you previously have probably sent commands to the computer through a graphical user interface (GUI) such as a web browser, text editor, photo editor, or any other of the myriad of computer programs now in existence. While the command line is initially daunting with its cryptic looking text, we will quickly see some of the many advantages it can have.

One of the many useful features of the command line will be using git to clone (download) a local copy of the curriculum hosted on learn.co. This will allow you to work offline and to save changes as you work through exercises and start programming!

To start, for Mac users, open the terminal application, for Windows, open “Git Bash”.

The first command to try out is pwd which stands for print working directory. This will tell you where you currently are in the computer's directory structure. Try it out.

The next essential command is cd which stands for change directory. This allows you to navigate to different folders on your computer's hard drive. Typing cd by itself will automatically take you to your home directory. Typing cd and a folder name will take you to that folder. Typing cd .. will move you one folder up in the hierarchy. Play around and trying moving between folders for a minute or two.

An extraordinarly useful feature when working on the command line is tab completion. This allows you to hit the tab button to autocomplete names once you have made a unique specification.

For example, if you navigate to your root directory by running the command cd, if you're on a Mac, you will probably have 2 folders within your root directory named "Downloads" and "Documents" (these are standard folder names created by default in most systems, although you may have renamed them, or your system may be different). With these, or longer folder names, it can sometimes become cumbersome to type the full folder name. instead, you can start typing the command and folder name such as "cd Dow" and then press tab to autocomplete. Like magic, the command line should complete the statement correctly to be cd Downloads. (Note: this will not work if you have another folder that begins with "Dow". Similarly, if you just typed cd D or cd Do followed by tab, the command line will not autocomplete, as the selection is not unique, because D or Do could both refer to either Documents or Downloads. Also note that these commands are case sensitive, and folder capitalization much be matched exactly.

Continuing with navigating the computer's hard drive, it's useful to know how to list files. This is done with the ls command, short for list.

You can also pass optional parameters to ls such as ls -a which list all files (including hidden files), ls -l which will give a long listing of files (including file size and last edit times) or you can pass multiple parameters simultaneously such as ls -al to produce a detailed listing of all files.

Also very useful is the wildcard parameter. For example, if you wanted to list all files in the current working directory that begin with a, you could type ls a*. Here, the asterix (*) denotes anything is allowed following the a. Similarly, to list all pdf files in the current working directory we could type ls *.pdf, or to list all text files, we could type ls *.txt.

Finally, as you continue to navigate the file directory from the command line it can be useful to be able to create new folders. To do this, use the mkdir command, which stands for make directory. Try it out with mkdir NewFolderName. Afterward, use the ls command to see that there is indeed a new folder, and if you wish, move into the new folder using the cd command.

Now that you can navigate the file directory using the command line, you're ready to download some course materials from the web to your local environment.

-

Create a folder on your computer for your course materials and navigate into it.

-

Then create a subfolder titled "section01" and navigate into that.

-

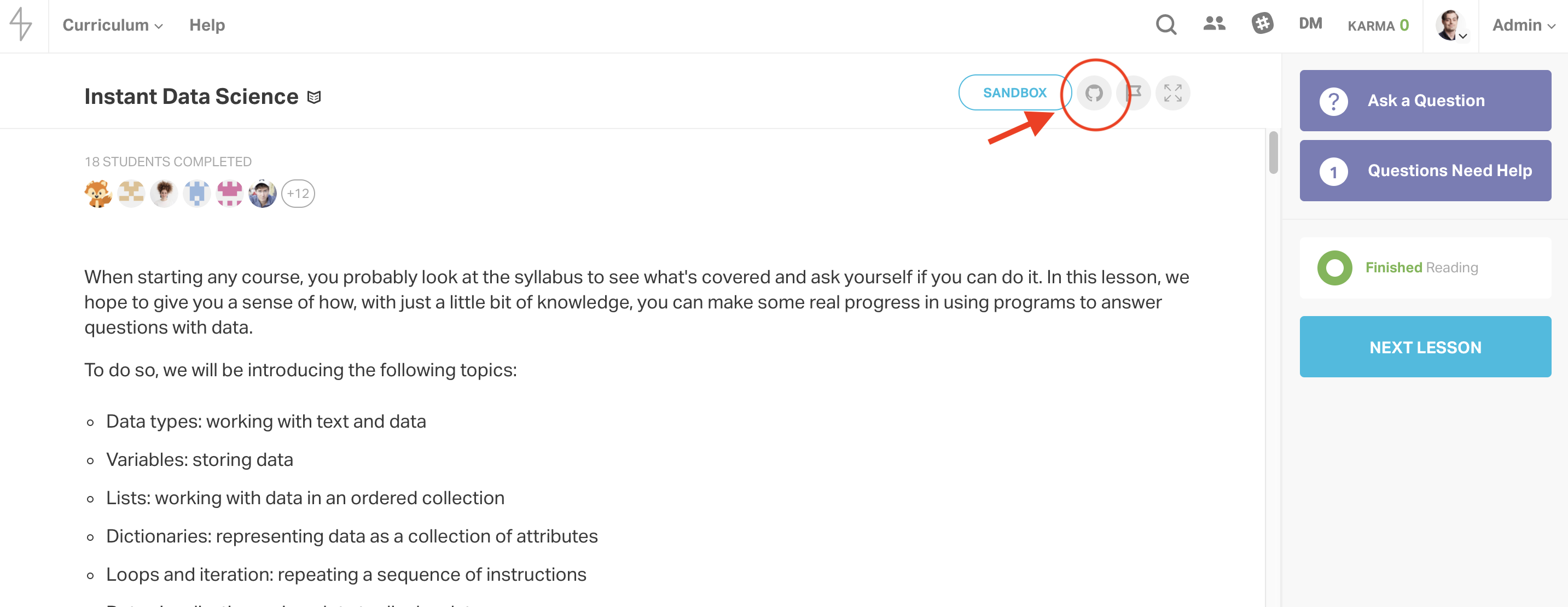

Return to your web browser and navigate to the lesson you want to download.

-

Click the GitHub icon

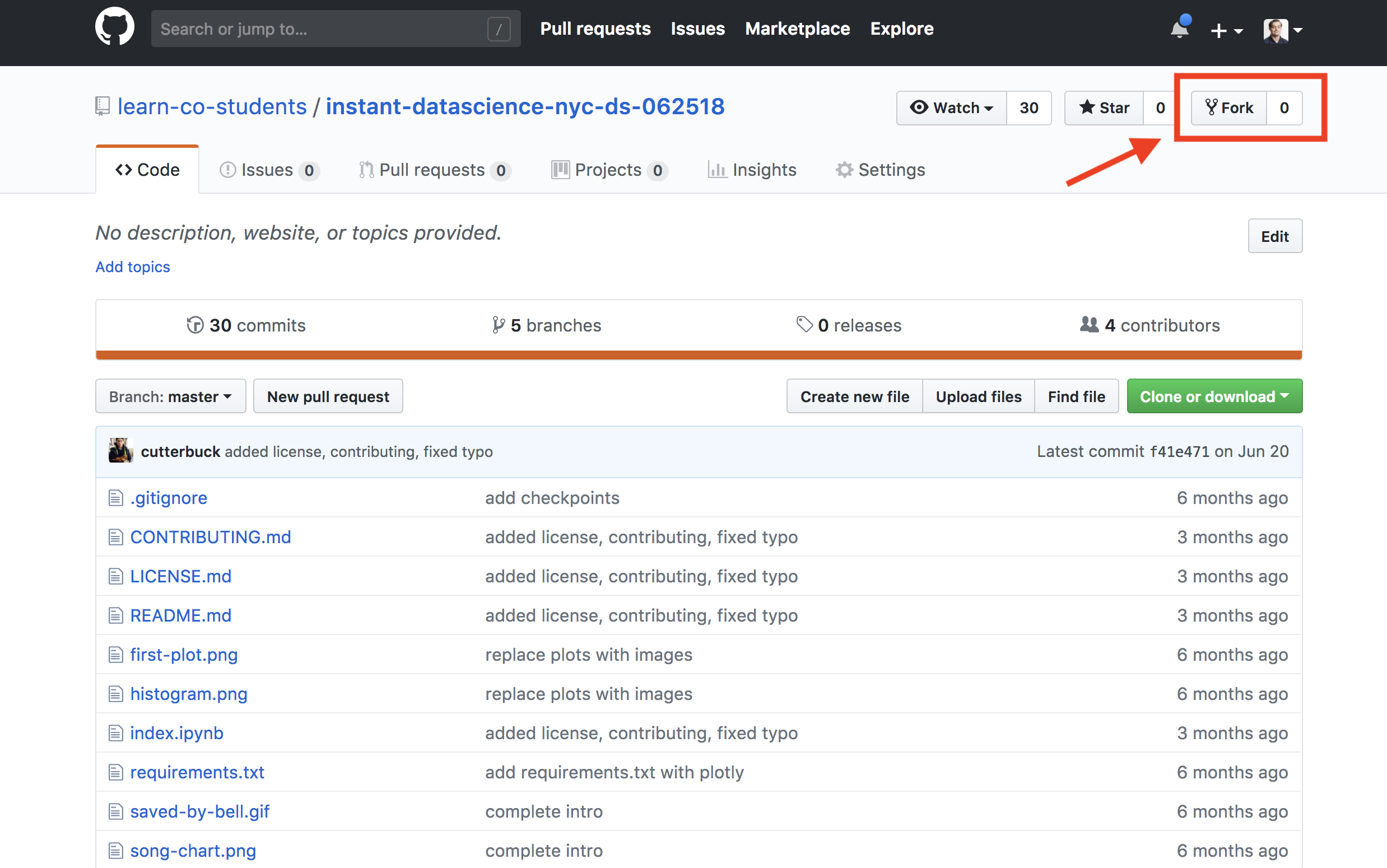

You'll be redirected to the associated GitHub repository like this.

- Click the fork button, as shown in order to create a copy to your personal account which you can edit and update.

One of two things will happen. Either it'll pop up a modal (window) and if you scroll to the bottom of it you'll see it says that you already have a fork. That is quite possible - learn auto-forks certain lessons for you. If that's the case, just click on the link to view your existing fork.

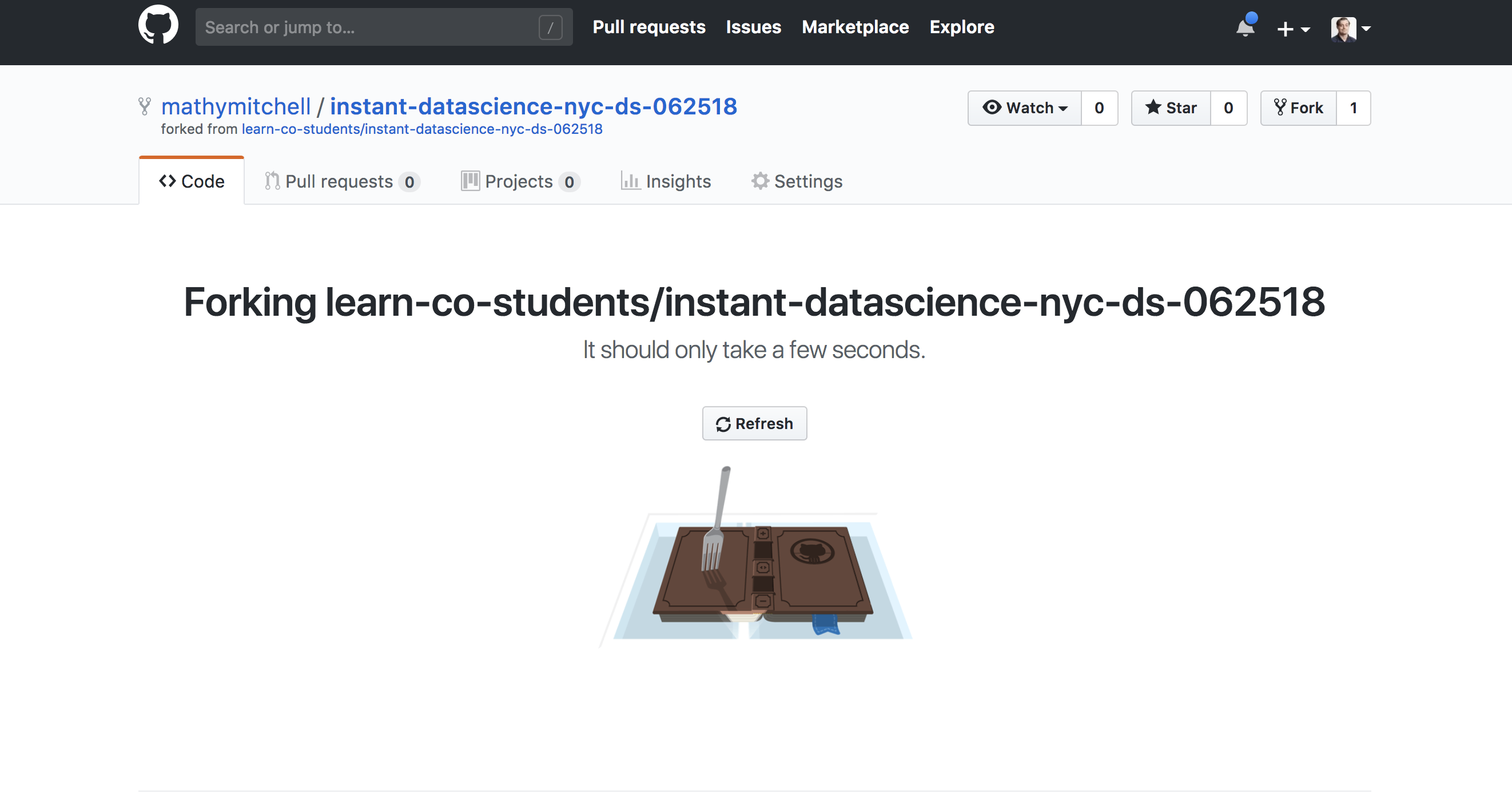

If you don't already have a fork, after a moment of this:

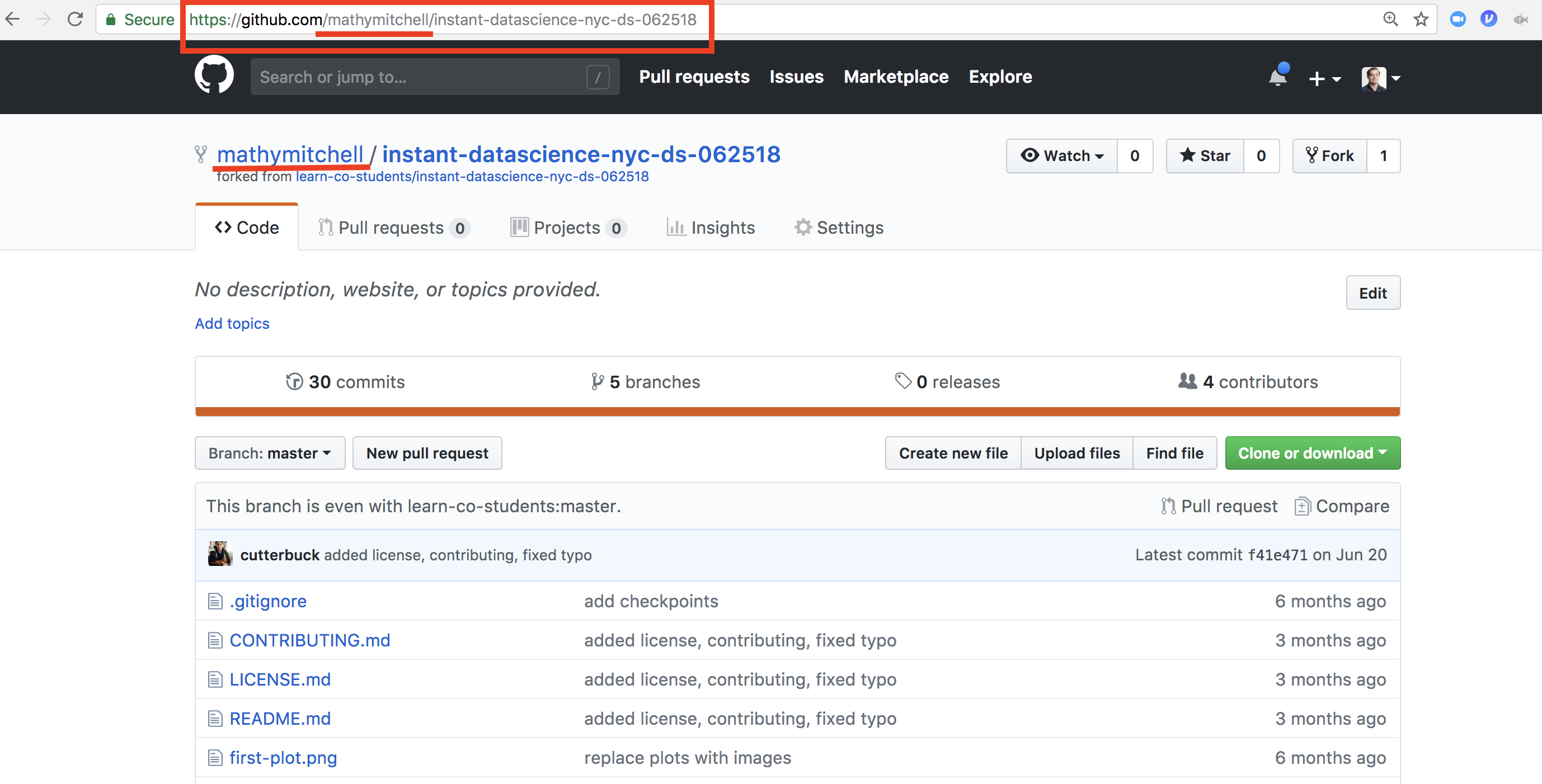

You'll be redirected to your new personal copy of the repository:

You'll be redirected to your new personal copy of the repository:

- Press cmd+L to highlight the url bar and cmd+c to copy the url (whenever we use

cmdto refer to holding down the command key on a Mac computer, on a Windows computer, hold down the control key instead) - Return to the terminal (you should be in your "section01" folder)

- Type: git clone and paste your repo url (cmd + v for Mac; for Windows, in git bash, shift + insert)

- Et Voila! The repository and all of its contents will be downloaded locally to your computer!

- Remember that we then need to cd into the new repository once we've downloaded it

- Our next step is to open our Jupyter Notebook locally (not on learn) using the command line

So, now that we understand a bit about how to use our terminal and how to clone GitHub repositories from our learn lessons, we should talk about the Jupyter Notebooks that will run most of the content in this course.

Make sure to activate your conda virtual environment in your terminal first by typing source activate learn-env. Then type jupyter notebook in your command line and press enter. Next, your default browser will open a new window or tab and you will see the list of files that are in your current directory (remember we want to be in the GitHub repo directory that we just downloaded).

Note: To stop a Jupyter Notebook, go to your command line where the notebook is running and press the control key + the letter C (

ctrl+c).

Second step is to click on the index.ipynb file which is the Jupyter Notebook we will be using in this and future labs and lessons. This will open a new tab where we will see the same content from learn!

Jupyter is a web application that allows someone to create and work with documents that have live code. It's a very popular tool among data scientists, as it allows for both explanations of thinking behind code as well as the code itself.

The notebook itself consists of cells. Double click on this content to see what I mean. Once we double click on a cell, we are in insert mode. This means that we are able to edit the cells, just as you would if this were a word document. We can tell that we are in insert mode because of the green border around the cell.

After entering insert mode for this cell, change some content. Don't worry about what you change as we can always undo it. We can revert our changes to a cell by making sure that we are still in insert mode and by pressing command + z on a Mac or control + z on Windows.

To get out of insert mode and see the effect of our changes, press shift + enter.

We have already seen, to alter the contents of a cell we simply double click on that cell, bringing us into insert mode, and then change the contents. Now let's see how to add, and delete cells from escape mode.

If we wish to quickly add a new cell we can do so with the following steps:

- Make sure we are not in insert mode, but in escape mode

- Remember we can tell we are in insert mode when we have a green border around our cell.

- To get out of insert mode and into escape mode, press shift + enter. Another option is to press the escape key.

- You will no longer see a cell bordered in green.

- Then press the letter

bto create a new cell.

To delete a cell we once again should be in escape mode, and then press the x key.

Of course, we'll want a way to undo our deletion. From escape mode, you can press z to undo deletion of a cell. Note that this is different from cmd + z. Pressing cmd + z while in insert mode undoes any changes inside of a cell while, whether these changes be deletions or text insertions. Pressing z from escape mode undoes the deletion of a cell.

Go to escape mode and press x. This cell disappears!

Then bring it back with z.

The current cell and every other cell in this lesson has been a markdown cell, meaning that it allows us to write text and stylize that text. For example, if you surround some text with two asterisks (**) on both sides, the text becomes bold. That's markdown.

Cells can also have a type of code. If we are writing in a cell that is for Python code, everything in that cell must be valid Python or we will see an error.

This is a python cell without valid Python so we will see an error File "<ipython-input-1-4e0ec4477064>", line 1

This is a python cell without valid Python so we will see an error

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

So, a cell must either be of type markdown or of type code, in which case all of the contents must be valid Python. It cannot be both. We can quickly change a cell from markdown to code with some keyboard shortcuts.

From escape mode, we change a cell to type code by pressing the letter y.

From escape mode, we change a cell to type markdown by pressing the letter m.

Anytime we create a new cell, say with the shortcut key b, the new cell will default to code mode. We can switch to escape mode and press the letter m to change the cell from code to markdown.

Press the key h while in escape mode to view the menu for all of Jupyter's shortcuts.

Ok, now that we know a little bit about adding and deleting cells, as well as changing cell types from markdown to code, let's focus on working with Python in Jupyter. We'll go into a large amount of detail about working with a Jupyter Notebook in Python, but the main takeaway is this: if we see a Python cell, we should press shift + enter on that cell.

The major gotcha in working with Python code is that we must execute the cells in order for Python to register the code in them. So for example, just seeing the cell where we define name to 'bob' below does not write that cell to memory.

name = 'bob'If we try to reference that variable later on without having executed the cell, Python will tell us that it is not defined.

nameTo execute or run a cell, we must press shift + enter on that cell (or when that cell is selected). Upon running a cell, Python will show the the last line of the cell's return value underneath. Let's run the cell below to see this:

age = 14

ageAs you can see the variable age is set to 14, so when the cell is run 14 is displayed underneath.

One tricky thing to note is that assignment, the action of assigning a variable, does not have a return a value. So, even though the cell is run, if the last line of cell is the assigning of a variable, nothing is displayed underneath.

hometown = 'NYC'Notice, even after pressing shift + enter on the code above, nothing is displayed below. But if we reference the variable hometown, we see that the cell was run as the variable was defined.

hometownYes, it's pretty confusing, but the important thing to take away is that we need to run our cells with Python code by pressing

shift + enterif we want Python to read our variables and functions and remember them later on. Remember, in the case of assignment, the return value isNone, which does not show an output. We can see this more concretely below by running the cell below:

NoneAs you read through labs we encourage you to press shift + enter on each of the Python cells that contains code. Often in labs, we will assign variables to data early on. Then we will ask you to work with data stored in those variables. To avoid going to the top of the lab to press shift + enter, it's best just to press that while reading along.

In this lesson, we learned about the command line, cloning github repositorites, and working with Jupyter notebooks. We saw that in Jupyter notebooks, we can either be in insert mode or escape mode. While in insert mode, we can edit the cells and undo changes within that cell with cmd + z on a Mac or ctl + z on Windows. In escape mode, we can add cells with b, delete a cell with x, and undo deletion of a cell with z. We can also change the type of a cell to markdown with m and to Python code with y.

Then we saw how to work with Python code in Jupyter notebooks. We saw that to have our code in a cell executed, we need to press shift + enter. If we do not do this, then our variables that we assigned in Python are not going to be recognized by Python later on in our Jupyter notebook.