The geostan package provides a user-friendly interface to Bayesian models for areal data. It is designed for accessibility and promotion of sound spatial analysis workflows. The package is still under development and will be released to CRAN later this year.

All of the models are fit using the Stan probabilistic programming language and the syntax draws heavily from the rstanarm package whenever possible in order to maintain consistency for users. It is designed to fit into a workflow that moves back and forth between R spatial analysis packages (sf, sp, spdep, ggplot2) and Stan-based Bayesian analysis (rstan, bayesplot, loo).

The following models are available:

- Generalized linear models, with optional exchangeable (non-spatial) `random effect’ or varying intercept terms.

- Eigenvector spatial filtering (ESF) models (known as principal coordinates of neighbour matrices (PCNM) in ecology), following Donegan et al. (2020). The spatial filter coefficients are estimated using Piironen and Vehtari’s (2017) regularized horseshoe prior.

- Intrinsic conditional autoregressive (IAR) models, using Stan code from Morris et al. (2019) following on the work of Besag (1974) and Besag and Kooperberg (1995).

- The scaled Besag-York-Mollie (BYM2) model introduced by Riebler et al. (2016) with Stan code from Morris et al. (2019) for disease mapping and similar applications, one of many variants of the original BYM model. This currently requires INLA to calculate the scale factor.

Since the package is not on CRAN, unmet dependencies must be installed first. You should first install Rstan by following the getting started guide. Then you’ll also need the following R packages:

if (!require(sf)) install.packages("sf")

if (!require(spdep)) install.packages("spdep")If you use Windows you can install geostan with the following R code:

install.packages("https://connordonegan.github.io/assets/geostan_0.0.1.zip", repos = NULL)

## though some may need:

install.packages("https://connordonegan.github.io/assets/geostan_0.0.1.zip", repos = NULL, type = "binary")If you use Linux you can install the package using:

install.packages("https://connordonegan.github.io/assets/geostan_0.0.1.tar.gz", repos = NULL)or, also for Linux users only, you may install from source:

remotes::install_github("ConnorDonegan/geostan")The package is not currently available for Mac users, sorry.

As a quick demonstration of the package we will use a simple features

(sf) dataset with county-level 2016 presidential election results for

the state of Ohio. Load the dataset with geostan and other helpful

packages:

library(geostan)

library(sf)

library(ggplot2)

library(rstan)

options(mc.cores = parallel::detectCores())

data(ohio)

## to learn about the data use:

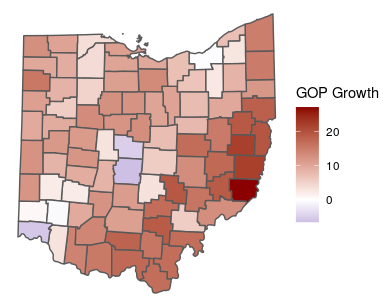

##?ohioWe are going to model change in the Republican Presidential vote share

from the historic average (2000-2012) to 2016 (gop_growth).

ggplot(ohio) +

geom_sf(aes(fill = gop_growth)) +

scale_fill_gradient2(low = "darkblue",

high = "darkred",

name = "GOP Growth") +

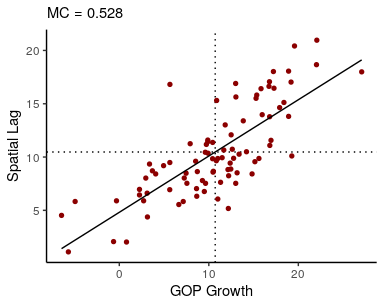

theme_void()We can use a Moran plot to visualize the degree of spatial autocorrelation in GOP growth. This plots each observation (on the x-axis) against the mean of neighboring observations (y-axis):

W <- shape2mat(ohio, "W")

moran_plot(ohio$gop_growth, W, xlab = "GOP Growth")## `geom_smooth()` using formula 'y ~ x'

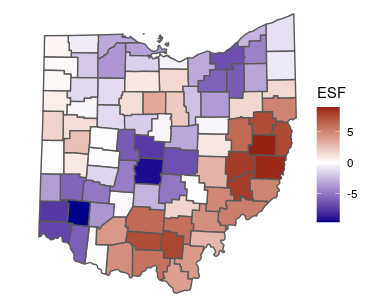

And we can estimate an ESF model by passing the model formula, data, and

spatial connectivity matrix to stan_esf:

## create binary connectivity matrix

C <- shape2mat(ohio, "B")

fit <- stan_esf(gop_growth ~ 1, data = ohio, C = C)Now fit is a list that contains summaries of estimated parameters, the

stanfit model returned by Stan, diagnostics, and other useful

information. We can extract the mean estimate of the spatial filter,

which is essentially a spatially varying intercept, with the spatial

function:

sf <- spatial(fit)$meanand visualize it with ggplot2:

ggplot(ohio) +

geom_sf(aes(fill = sf)) +

scale_fill_gradient2(low = "darkblue",

high = "darkred",

name = "ESF") +

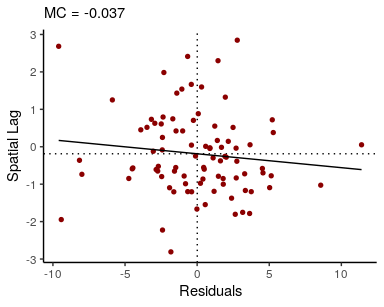

theme_void()We can also obtain summaries of the residuals and fitted values, and confirm that there is no residual spatial autocorrelation:

res <- resid(fit)$mean

f <- fitted(fit)$mean

## visualize residual SA

moran_plot(res, W, xlab = "Residuals")## `geom_smooth()` using formula 'y ~ x'

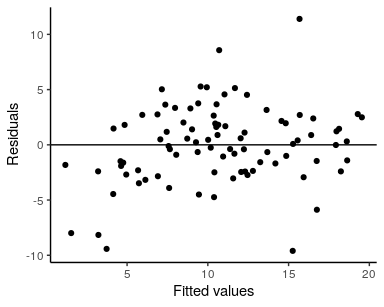

## fitted values vs. residuals

ggplot() +

geom_point(aes(f, res)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

labs(x = "Fitted values", y = "Residuals") +

theme_classic()Printing the model returns information about the model call (formula and likelihood function), diagnostics including residual spatial autocorrelation (Moran coefficient) and Widely Applicable Information Criteria (WAIC) for model comparison, plus a summary of the posterior distributions of top-level model parameters.

fit## Spatial Regression Results

## Formula: gop_growth ~ 1

## Spatial method: RHS-ESF

## Family: gaussian

## Link function: identity

## Residual Moran Coefficient: -0.049

## WAIC: 517.23

## Observations: 88

## RHS global shrinkage prior: 1

## Inference for Stan model: esf_continuous.

## 4 chains, each with iter=2000; warmup=1000; thin=1;

## post-warmup draws per chain=1000, total post-warmup draws=4000.

##

## mean se_mean sd 2.5% 25% 50% 75% 97.5% n_eff Rhat

## intercept 10.706 0.006 0.421 9.876 10.419 10.708 10.998 11.503 5258 1

## sigma 4.080 0.008 0.377 3.410 3.816 4.050 4.315 4.891 2325 1

##

## Samples were drawn using NUTS(diag_e) at Wed Jul 1 18:53:49 2020.

## For each parameter, n_eff is a crude measure of effective sample size,

## and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor on split chains (at

## convergence, Rhat=1).

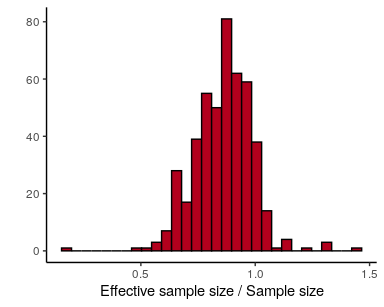

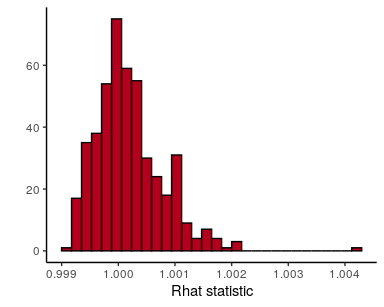

The Rhat statistic should always be very near 1 with any divergence

from 1 indicating that the chains have not converged to a single

distribution. Values further than, say, 1.01 are troubling. The model

includes numerous parameters, so the most efficient way to evaluate the

diagnostics is to plot them together. To examine autocorrelation in the

chains, we can use the estimate of the effective number of posterior

samples (n_eff):

## check effective sample sizes

stan_ess(fit$stanfit) +

theme_classic()## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

## check Rhat statistics

stan_rhat(fit$stanfit) +

theme_classic()## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

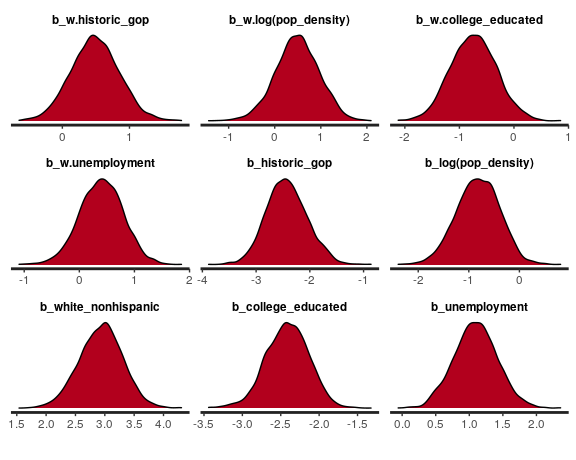

We can fit the model the found in Donegan et al. (2020) with a Studen’t t likelihood function and spatially lagged covariates:

fit3 <- stan_esf(gop_growth ~ historic_gop + log(pop_density) + white_nonhispanic + college_educated + unemployment,

slx = ~ historic_gop + log(pop_density) + college_educated + unemployment,

scalex = TRUE, # all X variables scaled to mean = 0, std. dev = 1

family = student_t(),

data = ohio,

C = C)The spatial connectivity matrix C is row-standardized internally

before calculating the spatially lagged covariates, so the constructed

spatially lagged variables are the mean spatially lagged values.

The plot and print methods call the bayesplot package, and they

accept a character string of parameter names such as 'beta' for

coefficients, 'beta_ev' for eigenvector coefficients, 'esf' for the

spatial filter. You can also provide more specific names such as

'b_unemployment'.

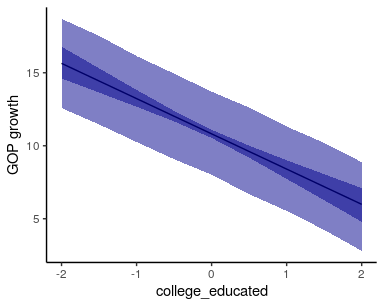

plot(fit3, "beta", plotfun = "dens")The posterior_predict function can be used for posterior predictive

checks together with the bayesplot package (see ?posterior_predict)

and for hypothesis testing. The following example shows how to use it to

visualize marginal effects:

# create data.frame all but one of the variables at their mean value (all have mean = 0, std. dev = 1)

newdata <- data.frame(historic_gop = 0,

pop_density = 1, # log(1) = 0

college_educated = seq(-2, 2, by = 0.5),

unemployment = 0,

white_nonhispanic = 0

)

pred.df = posterior_predict(fit3, # fitted model

newdata, # data for predictions

spatial = FALSE, # set the spatial component to zero

summary = TRUE, # return a data.frame with 95% credible intervals

)

# plot the mean of the predictive distribution

fig <- ggplot(pred.df, aes(x=college_educated)) +

geom_line(aes(y = mu))

# add credible interval around the mean

fig <- fig +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = mu.lwr,

ymax = mu.upr),

alpha = .5,

fill = 'darkblue')

# add cred. interval for the predictive distribution

fig <- fig +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = pred.lwr,

ymax = pred.upr),

alpha = 0.5,

fill = 'darkblue')

fig +

labs(y = "GOP growth") +

theme_classic()Besag, J. (1974). Spatial interaction and the statistical analysis of lattice systems. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 36(2), 192-225.

Besag, J., & Kooperberg, C. (1995). On conditional and intrinsic autoregressions. Biometrika, 82(4), 733-746.

Besag, J., York, J., & Mollié, A. (1991). Bayesian image restoration, with two applications in spatial statistics. Annals of the institute of statistical mathematics, 43(1), 1-20.

Donegan, C., Chun, Y., & Hughes, A. E. (2020). Bayesian estimation of spatial filters with Moran’s eigenvectors and hierarchical shrinkage priors. Spatial Statistics, 100450.

Morris, M., Wheeler-Martin, K., Simpson, D., Mooney, S. J., Gelman, A., & DiMaggio, C. (2019). Bayesian hierarchical spatial models: Implementing the Besag York Mollié model in stan. Spatial and spatio-temporal epidemiology, 31, 100301.

Piironen, J., & Vehtari, A. (2017). Sparsity information and regularization in the horseshoe and other shrinkage priors. Electronic Journal of Statistics, 11(2), 5018-5051.

Riebler, A., Sørbye, S. H., Simpson, D., & Rue, H. (2016). An intuitive Bayesian spatial model for disease mapping that accounts for scaling. Statistical methods in medical research, 25(4), 1145-1165.

Watanabe, S. (2013). A widely applicable Bayesian information criterion. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 14(Mar), 867-897.