| title | author | __defaults__ | linkcolor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Git and Unix Bootcamp |

Michael Ivanitskiy (mivanits@mines.edu) |

|

blue |

- polls

- introduction

- installing git and bash

- navigation in bash

- common bash utilities

- pipes, redirects

- absolute basics of vim

- basic introduction to git: cloning, staging, commiting, pushing, pulling

- working with multiple people in the same git repository

- GitHub-specific tools: pull requests, CI/CD

- which operating system are you currently using? (Mac, Windows, Linux)

- have you used a terminal (bash, zsh, fish, cmd, PowerShell) before?

- have you used an sh-compatible terminal before?

- have you used git or github before?

Some definitions:

- an Operating System is software that manages software and other hardware for a computer, and provides common services.

- MacOS, Windows, Android, iOS, and the various Linux distributions (Ubuntu, Mint, Arch, etc) are all operating systems

- a command-line shell is a program that interprets a language that allows the user to have access to operating system services

- these services include moving files around, running or stopping other programs, and pretty much anything you can expect to be able to do with a computer

- a version control system is responsible for tracking and managing changes to source code and programs. when working on all but the smallest pieces of code, this becomes extremely useful. Think of it as google docs edit history, but for source code

- the only version control system that you should worry about learning is git -- for now, all others see relatively niche application in industry

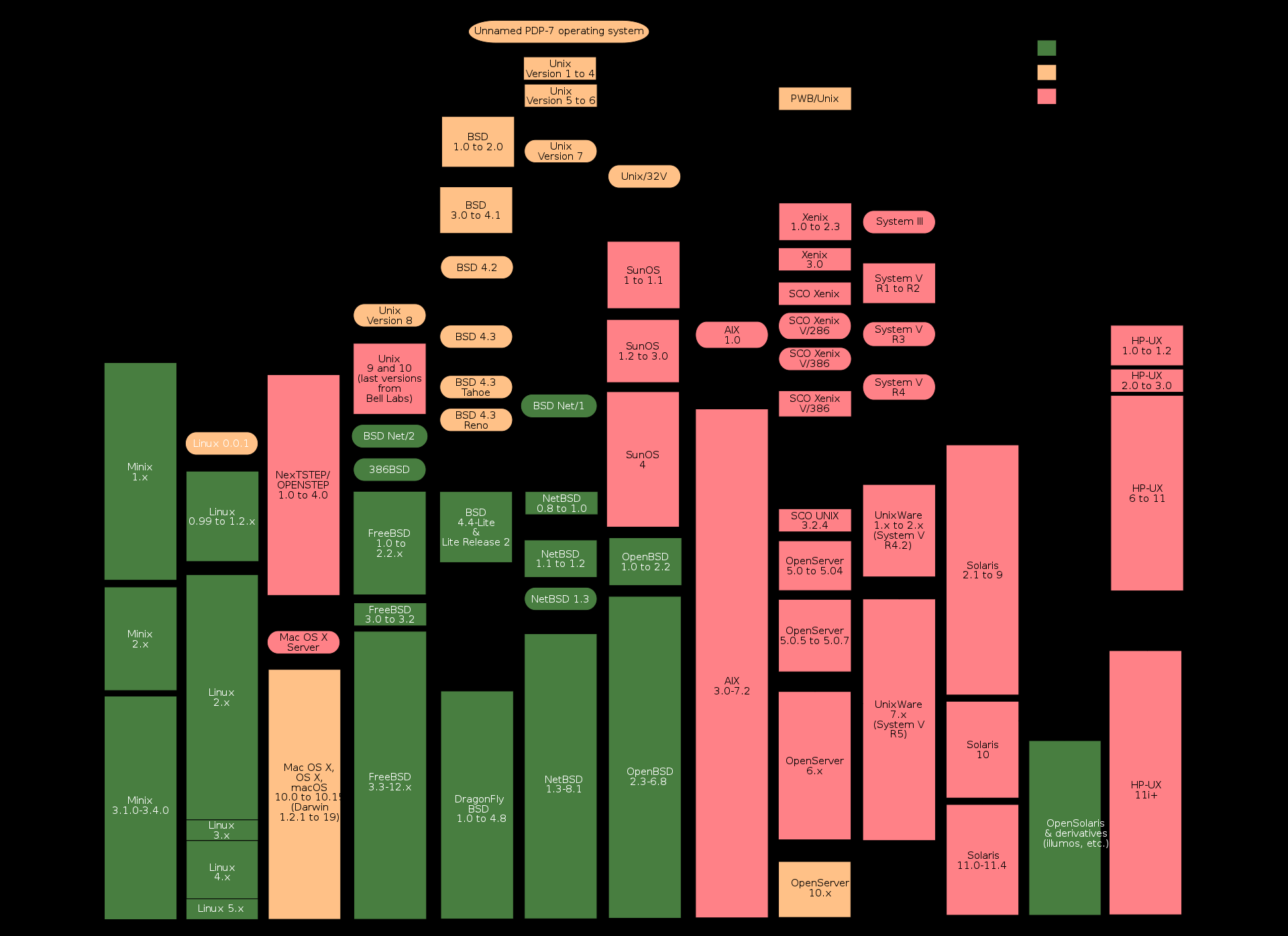

Now, some history:

- "Unix" is a family of operating systems, originating from Bell Labs in 1969

- the GNU project (a recursive acronym standing for "GNU's not Unix!") was created in 1983 with the goal of giving computer users freedom in their use of computing devices. it has created a wide variety of open-source tools, including bash (Bourne-again shell) in 1989 to replace the original Bourne shell for Unix

- "Linux" is a family of open-source "unix-like" operating systems, and most "serious" computing is done on Linux today.

- "git" is a version control system originally created to manage the development of the Linux kernel, but has been widely adopted in all areas of software and is the de-facto standard for version control

if you're prompted during installation to select a default text editor for editing commits, I reccomend nano, but feel free to choose whatever you're comfortable with

- MacOS comes with either bash or zsh, depending on how recently you've updated. simply start up the "Terminal" program

- to install git, go to git-scm.com

Windows comes with both the cmd shell and PowerShell, but you'll want to install bash. Navigate to gitforwindows.org, and download and run the installer.

NOTE: When prompted about line endings, select "Check out as-is, commit LF"

when the installation is complete, start up "git bash" from the start menu

Almost all distributions of Linux come with bash or some other sh-compatible shell, and git.

after installing, launch your terminal, type

git --versionand hit enter. It should print the version to the console.

now, type

helpthis should:

- tell you what shell you're using

- remind you how to use help commands

- give the basic keywords of your shell language

firstly, note that:

- stackoverflow is your friend!

- adding

--helpto almost any command will display a help message explaining how to use it *is commonly used as a "wildcard" -- it will "match" any character or string of characters- text in curly braces

{}will be used to mean "replace this with text relevant to your usage"- for example,

cd {path}changes your directory, but you should replace{path}with an actual path, such asDownloads - curly braces do have their own special meaning in bash, so be careful (array construction, parameter expansion, and output grouping. those are beyond the scope of this tutorial)

- for example,

- if you get stuck in what looks like a text editor, its probably either

lessorvim. try:- pressing

q(this existsless) - pressing

esc, then:, thenq(this exits vim)1

- pressing

-

ctrl+Cwill close the current process -

ctrl+Zwill pause the current command, resume it in the background or foreground withfgorbgrespectively -

TABwill try to autocomplete a command or file -

$\uparrow$ (up arrow key) will bring up the most recent command -

ctrl+Rwill search among the previous commands (this is very useful) -

ctrl+Aandctrl+Ewill bring the cursor to the start or end of the line, respectively

when you run commands, it is usually important which files are around. these commands let you move around in and modify the filesystem

-

pwdwill print the working directory (your current location in the filesystem) -

ls: list every file/folder in the current directoryls -alwill print it in a list format with some more data about the file, notable the filesize in bytes and the date on which it was last modified- note that

.means "the current directory" and..means "the parent directory"

-

cd {path}will change directory to the specified path -

mkdir {path}will create a directory at the given path -

rmwill remove a file (be careful!!)rm -rfwill remove a directory and its contents

-

cp {path1} {path2}andmv {path1} {path2}will copy or move the files specified in{path1}to{path2}, respectively.

you can do really clever things too, like copy the contents of a directory:cp *.txt textfiles/will copy all files ending in.txtinto the foldertextfilescp -R data moredatawill copy the contents of the folderdata

-

find -name {name}will find all files matching{name}

in the unix philosophy, programs should input and output streams of text.

- a program can read input from

stdin, which is equivalent to prompting the user for some text - a program writes its output to

stdout - a program writes any errors or warnings to

stdin

For modern software, this isn't always the dominant paradigm, but it can still come in handy. The following commands can be used redirecting the outputs of a program:

>redirects thestdoutof the preceeding command into the file following the sign. this will overwrite any existing file- note that anything still printed to the console is from

stderr

- note that anything still printed to the console is from

2>redirectsstderrto the given file- can be used in combination with

>:

myprogram > output.txt 2> errors.txt

- can be used in combination with

>>appends thestdoutof the preceeding command to the specified file, leaving the existing contents in place|will sendstdoutof the preceeding command asstdinto the following command

bash has many built-in programs, there are many thousands you can install, and you can even write your own. here are a few I find myself using regularly.

cat {file}will print the contents of a text file to the console. only useful alone for short filescat {file} | lesswill open a simple viewer, pressqto exit- (more on what

|does later)

- (more on what

head {file} -n {number}ortail {file} -n {number}will print{number}lines from the beggining or end of the specified file, respectively

diff {file1} {file2}will give the difference between two text filesgrep {text} [filename]will return lines from[filename]with{text}in them- this is most useful when searching for something in a file:

cat my_logfile.txt | grep "WARNING"

- this is most useful when searching for something in a file:

tarcombines multiple files into a "tarball", which is a single file that contains multiple files within it. usage can be complicated- compressing:

tar -zcvf compressed_files.tar.gz folder/ - decompress:

tar -zcvf compressed_files.tar.gz folder/

- compressing:

gzipcompresses a single filenano {filename}opens thenanotext editor on a filenanohelpfully has instructions on the bottom for how to use it, so you're less likely to get stuck- this is very useful for editing text files when you're connected to a big supercomputer without a desktop

any command you can run in the command line, you can put in a file

- printing to console: use

echo "{stuff}" - using variables: all variables in bash are strings. it's a bit weird.

- define using

VARNAME="stuff" - use later by writing

$VARNAME

- define using

- referencing command line args: in general,

$1is the first arg,$2is the second, and so on - control flow:

- if-then blocks generally look like

but the

if {command}; then {code} fi{command}can take many forms."$VARNAME" == "test"will evaluate to true, but you can test for the existence of files and do many other things - for loops: look them up if you must

- if-then blocks generally look like

a simple example script:

echo "you are located in:"

pwd

dirname=$1

searchname=$2

echo "we will create and enter the directory $dirname"

mkdir $dirname -p

cd $dirname

fname="programs-$(date +%s).txt"

ps > $fname

cat $fname | grep $searchnamea few commands for interacting with your operating system

note: these work on linux/wsl, some will work on windows with git bash, and I have no idea if they work on macOS)

psstatic process listkill {PID}kill a process with the given id (usepsto get the id)fgandbgmove a process to the foreground or backgroundtopdynamic process list, will keep updating until you doctrl+Chtopwill also display cpu utilization. useful for seeing if your code is actually properly parallelized, and also for looking kinda cool

sudo {command}DANGEROUS: this is "superuser" mode, which will let you do very dangerous things and possible brick your computer. use with extreme caution. using it on a cluster probably won't work and might get you in trouble

git is a distributed version control system. what does "git" stand for? the readme of the source code states:

"git" can mean anything, depending on your mood.

- Random three-letter combination that is pronounceable, and not actually used by any common UNIX command. The fact that it is a mispronunciation of "get" may or may not be relevant.

- Stupid. Contemptible and despicable. Simple. Take your pick from the dictionary of slang.

- "Global information tracker": you're in a good mood, and it actually

- works for you. Angels sing, and a light suddenly fills the room.

- "Goddamn idiotic truckload of ****": when it breaks.

git, used properly, will make sure that you never, ever, ever end up in a situation where you lose code. If you make changes to your code, you can go back in the commit history and find the last working version. if you accidentally delete everything, git will let you recover it. if your computer gets blown up, your code is backed up. If you're working on a collaborative project, git will help you resolve issues when you and your collaborators modify code at the same time.

git is supposed to be simple, but can often feel anything but. Here are the 7 absolute basic commands you need to know:

git help...prints help- note the commands:

git help tutorial,git help everyday,git help workflows

- note the commands:

git clone {url} {folder}clones the git repo at{url}into{folder}{url}is usually a github link likehttps://github.com/someuser/repositoryname- if

{fname}is not given, it will clone into a directory with the name{repositoryname}

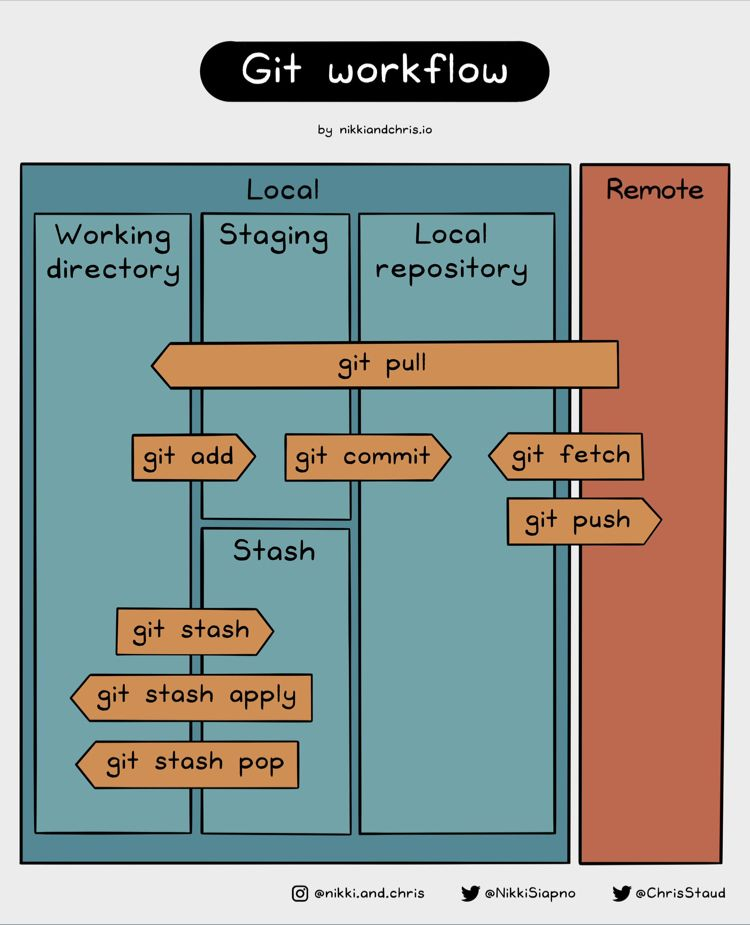

git statusshows you what's going on in the current repositorygit add {files}"stages" files (selects them for being commited)git commit"commits" your changes -- they are now added to the official list of changesgit pullsynchronizes your client by pulling files from the remotegit pushsends whatever changes you have commited to the remote

A "git repository" is a directory in which certain files are tracked by git. when you run any git command, it looks for a .git file in the current directory, and recursively in every parent directory. that folder contains the whole history of all changes you've commited to the repository.

Your local history can synchronize with a "remote" repository2 -- this is the primary way of backing up your code, and collaborating with others. GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket, and other websites provide (free) hosting of git repositories. We will be using GitHub in this tutorial.

- When you make changes, git does not automatically do anything

- To track changes, you must first add them using

git add {files}(git add .will add everything in the current directory)- you can exclude files via a special

.gitignorefile, which you may look up the documentation for. this is useful if you have built binaries that you dont want to upload, have files with API or SSH keys you don't want to make public, or have a bunch of data that you don't want to upload.

- you can exclude files via a special

- When you run

git status, it will show you which changes have been added and which have not - when you run

git commit, it will add all the changes along with your message to a "tree"

gitGraph

commit id: "initial commit"

commit id: "implemented a feature"

commit id: "fixed a bug"

When you're working on code with other people, want a persistent version of your code that is always functional, or otherwise need multiple versions of your code, branches are your friend. Git handles history as a "tree", where the main trunk is called main (somtimes master on older systems), and you can branch off at any commit. After making changes, you can then re-merge the branch

gitGraph

commit

commit

branch develop

commit

commit

commit

checkout main

commit

commit

merge develop

commit

commit

key commands:

git branchsee the active branchesgit branch {name}create a new branchgit checkout {name}switch to a branch

merging branches in the command line is possible, but I'll be covering how to do it in the github client

Github is a platform for hosting git repositories. It is free, and has a lot of features. You can find other peoples's code, "fork" it (make a copy that belongs to you), make changes, and then merge your changes into the original repository. It also acts as a sort of social network for anything code-related, and having some open source projects up on your github can be a great way to stand out to employers.

The main thing to know about what github adds is Pull Requests:

A pull request "pulls" changes from one branch onto another branch -- this terminology can be confusing, but in the interface the "source" branch is on the right and the "target" branch is on the left.

Github also supports various CI/CD features, which let you automatically run code upon certain actions, like creating a pull request to the main branch. These are beyond the scope of this bootcamp, but I'm happy to chat about them sometime.

(try to do this all in the command line)

- install bash and git, if you haven't already

- go to github.com and create an account if you don't have one 3. log in to github on your system. this will vary depending on your OS, and you may have to generate a token on the website

- fork and clone your fork of the repository https://github.com/mivanit/bash-git-bootcamp

- change to the "user-dev" branch

- navigate to the "userdata" folder

- create and enter folder with your mines username

- make some changes here -- write a script, add a file, whatever you want

- add, commit, and push your changes

- merge your changes with the

user-devbranch on my repository

- bash is useful for talking to computers and manipulating filesystems at scale

- git and github will prevent you from ever losing your code

- git docs

- bash docs

- bash cheat sheet (there are many online)

- pandoc

- how to use git in the command line is good to know, but there are many graphical interfaces for it. I reccomend GitHub Desktop

Footnotes

-

if you want to start a local-only git repository, you can run

git initin a repository. this will create a.gitfolder, and start tracking changes. If you then want these to then be synced with the cloud, you will need to usegit remote add origin {url}. for this tutorial, we assume the creation of a repository on github first] ↩