-

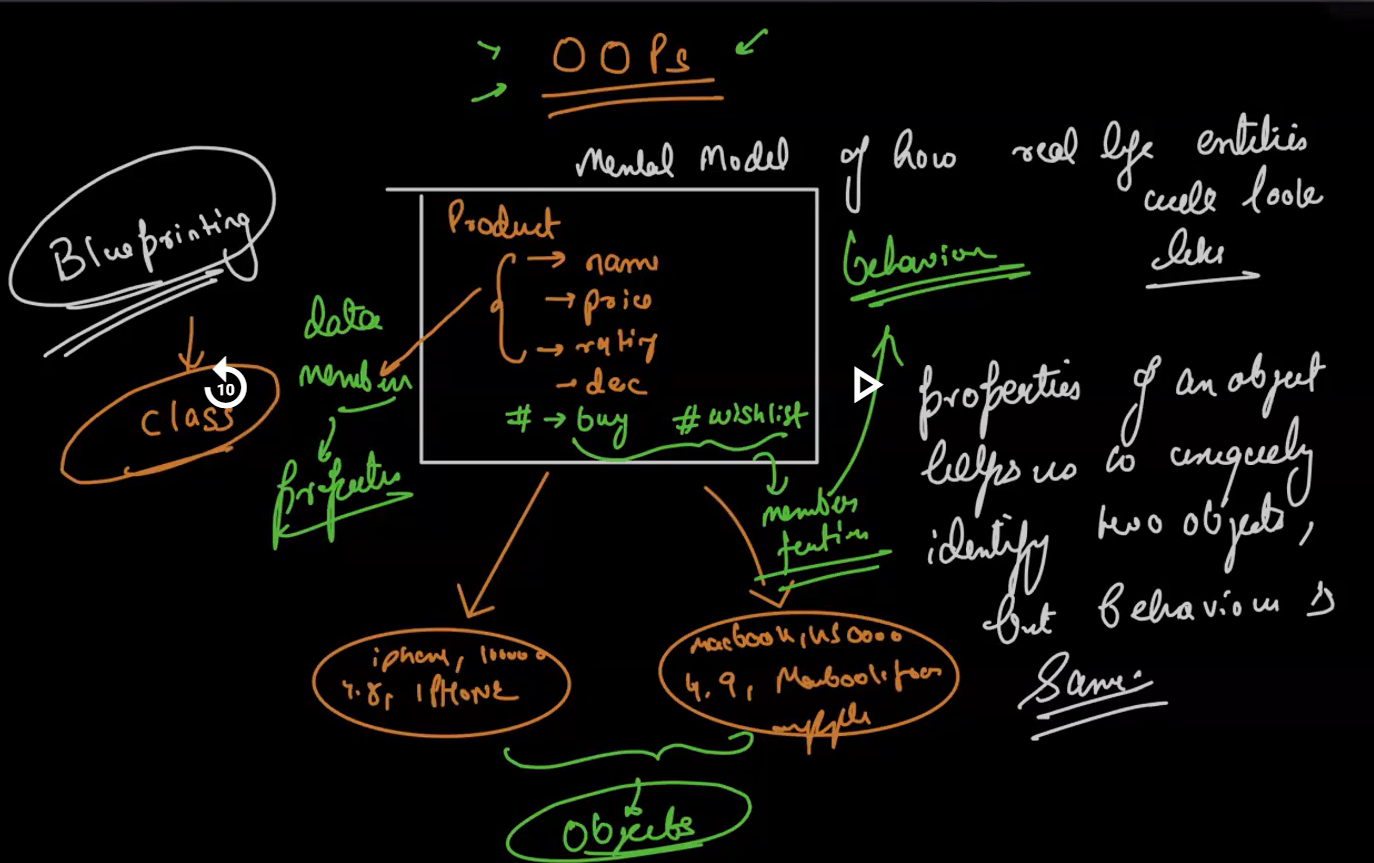

In order to prepare big applications where we have a lot of data coming here and their, and you want to represent the logic in terms of frontend backend and whereever you are storing it we need to have some blueprinting mechanism. So that we can prepare a logical mental model.

-

Once we have the blueprinting then we can start populating values to it and construct real life enities. This blueprinting paradigm is known as

Object oriented programming. -

OOPs can be a bit different from programming language to programming language. Because there are sometimes language based restrictions

-

In Javascript the OOPs is completely different maybe the keywords have similarities with other languages but the concept and the usage are different from them

-

Preparing the blue print of the mental model of whatever real life entity we have is known as

class -

Once the blueprint is ready we can created multiple real life entity. ex: products. These real life entities are called

objects. -

Propertiesof an object helps us to uniquely identify two objects but behaviour is same(ex: Display a product, buy a product etc). In technical term the properties are termed asdata membersand the behaviour are calledmember function -

Class Demonstration Screenshot:

- In JS we have a

classkeyword. Using which we can prepare blueprint.

class <name>{

// Properties

// Behaviour

}Using this we can create entities/objects

- Now in order to create and manage the entities we have two new keywords

newandthis

Now these 3 kewords together i.e class, new and this forms the basis of how we write OOPs in JS

-Syntax to create a Class

class Product {

// no need of let var const

name;

price;

discount;

desc;

display() {

// no need to function keyword

}

buy(){

// no need to function keyword

}

}- Syntax to create an object

const p = new Product();To understand the syntax of object, we need to first understand this

-

thiskeyword: except one casethisalways refers to the calling site/context. From what context and what reference we are calling it makes the difference . this will not always point to the same object from which we are making the function call -

The one case where

thisdoesn't refer to the calling context is whenarrow functionis getting used. Inside arrow function this doesn't refer to the calling context. By default in arrow function this is going to be resolved lexically. Code Demo

newkeyword: The sole purpose of new keyword is to create a brand new plain javascript empty object nothing more nothing less

class Product {

// no need of let var const

name;

price;

discount;

desc;

display() {

// no need to function keyword

}

buy(){

// no need to function keyword

}

}

const p = new Product()-

When we write the name of the class (and in this case Product) and pairing it up with a pair of parenthesis, this particular syntax is calling a

constructorof the class. -

Now

what's the constructor? -> Whenever we create a object of a class,constructoris the first function that's actually getting called.

- What's the purpose of this constructor? -> Let's say we are creating a object we want to initialize the object with some corresponding values or let's say setup some connection whatever we want to do which should happen when we are creating a new object all of that logic we put inside the constructor.

-> It's a special method -> In the above example we have not written any constructor so javascript with use the default constructor. So, whenever we write the class name with a pair of () it calls the default constructor all together So, now if we do

console.log(p);

// Product { name: undefined, price: undefined, desc: undefined }

// there's no error at all it calls the default constructor and since there's no property assigned all of them returns undefined-

Let's say we want to initialize our own constructor. The new keyword is creating a brand new plain empty object and then actually we are calling the constructor

-

We can create a constructor using the keyword constructor(){}

constructor(){

}- Now, as we know the new keyword creates a brand new empty object and we are calling the constructor product(). This constructor is getting called w.r.t to the brand new plain empty object, so this brand new plain empty object is the calling context. Now if we use this inside contructor(){this}. Then this keyword will point to brand new plain empty object. Now we can do something like

constructor(n,p,d){

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

this.desc = d;

}So, the contructor is pointing to the plain empty object and we are manually creating a key value pair where the key is name and the value is whatever we pass inside the name. For example:

const p = new Product("Bag", 100 ,"a cool bag");

// Product { name: 'Bag', price: 100, desc: 'a cool bag' }- A question might pop that a constructor is a method that means its like a function and in a function we return something but here we are not returning anything. ->> Inside the constructor if we return anything primitive then there's no effect it'll technically just avoid it, because constructor is meant to do something with an object, it's meant to return an object. If we return a primitive the sole purpose of constructor is gone.

Important We can't do constructor overloading in JS

- Function Constructor: Whatever we are doing with class we can achieve it with functions as well and the behaviour is also same, class is just a wrapper over

function Product(n, d, p) {

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

this.desc = d;

}

const p = new Product("Bag", 100, "a cool bag");

console.log(p)

// Product { name: 'Bag', price: 'a cool bag', desc: 100 }-

What is an access modifier ? -> Access modifier maintaince what is visible outside and what is not visible outside in a class To make it private Javascript has a shorthand:

#NameOfTheVariableThatNeedsToBePrivate -

Let's say we want to expose a functionality to user from where they can get some properties and set some properties, do we need to make them public? -> NO, we can make getter setter's

class Product {

#name; //private

constructor(n, p, d) {

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

this.desc = d;

}

// setter

setName(n) {

if (typeOf(n) = ! 'string') {

console.log("Invalid name passes");

return;

}

this.#name = n;

}

// getter

getName(n){

return this.#name;

}

}

const p = new Product("Bag", 100, "a cool bag");

p.setName(-1);

// Invalid name passed

console.log(p)

// Product { name: 'Bag', price: 'a cool bag', desc: 100 }Well in Js we get better syntax to write getter and setters, So it doesn't look like function and still looks like we are setting a value only but while setting also a whole set of logic that gets executed. We can use the get and set keyword. So now we access them as properties not function.

class Product {

#name; //private

constructor(n, p, d) {

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

this.desc = d;

}

// setter

set setName(n) {

if (typeOf(n) = ! 'string') {

console.log("Invalid name passes");

return;

}

this.#name = n;

}

// getter

get getName(n){

return this.#name;

}

}

const p = new Product("Bag", 100, "a cool bag");

p.setName = "test";

// Invalid name passed

console.log(p)

// Product { name: 'Bag', price: 'a cool bag', desc: 100 }So, this how we extract out internal details of class from the outside out that is not necessary for other to know

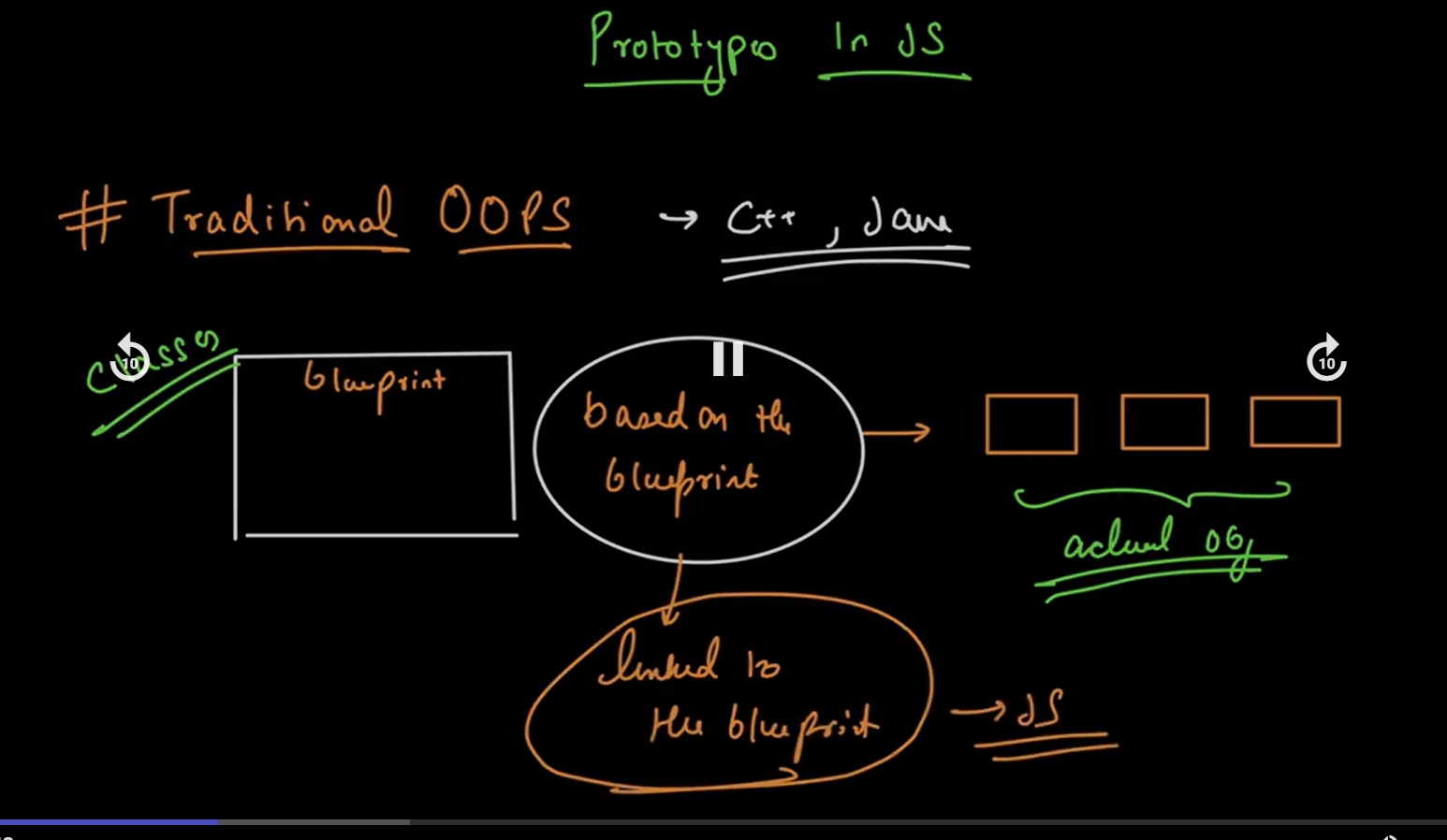

- Traditional OOPs: In traditional languages such as C++, Java we have a abstract blueprint and based on these blueprint we actually create real life entities.

-

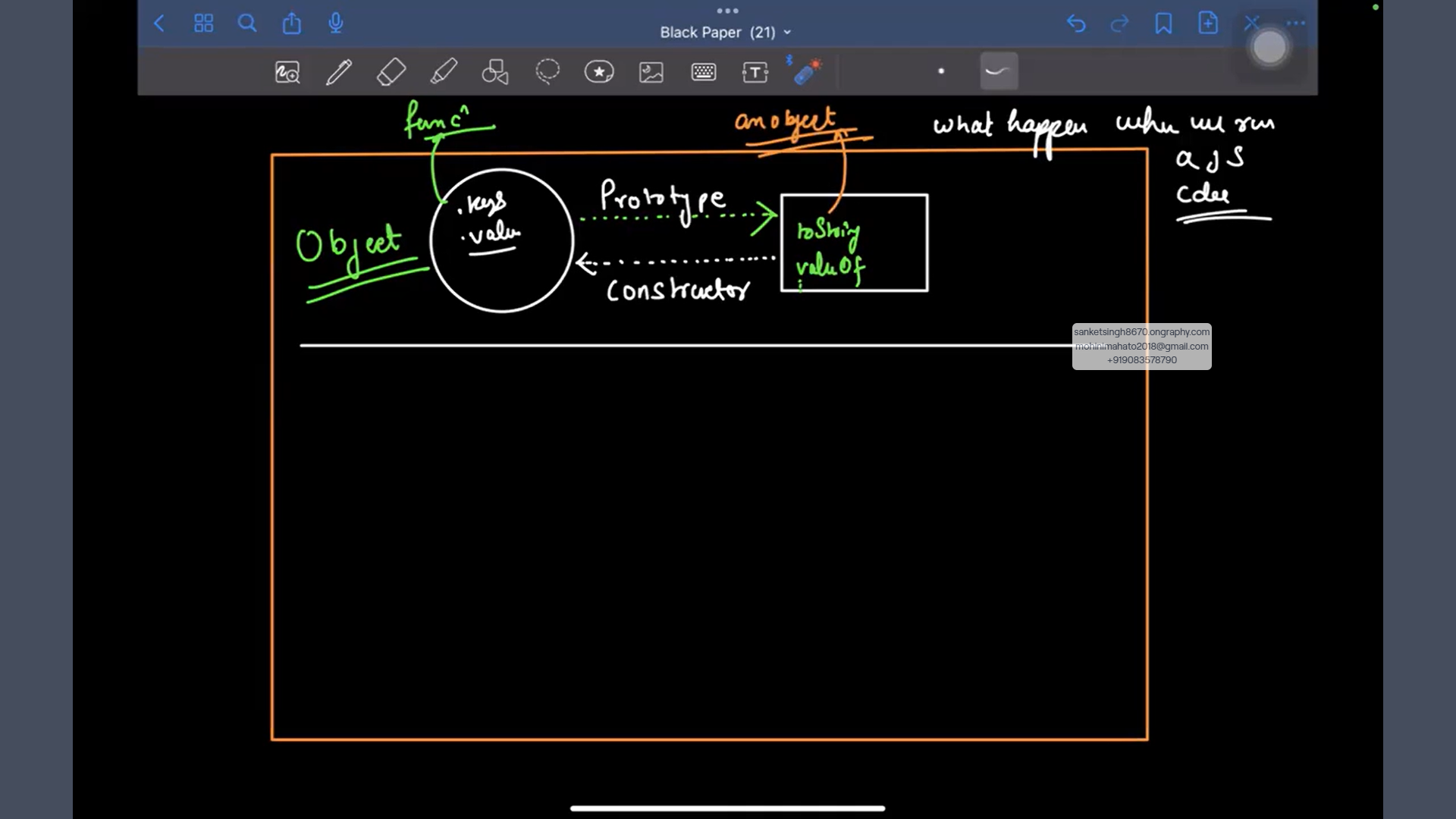

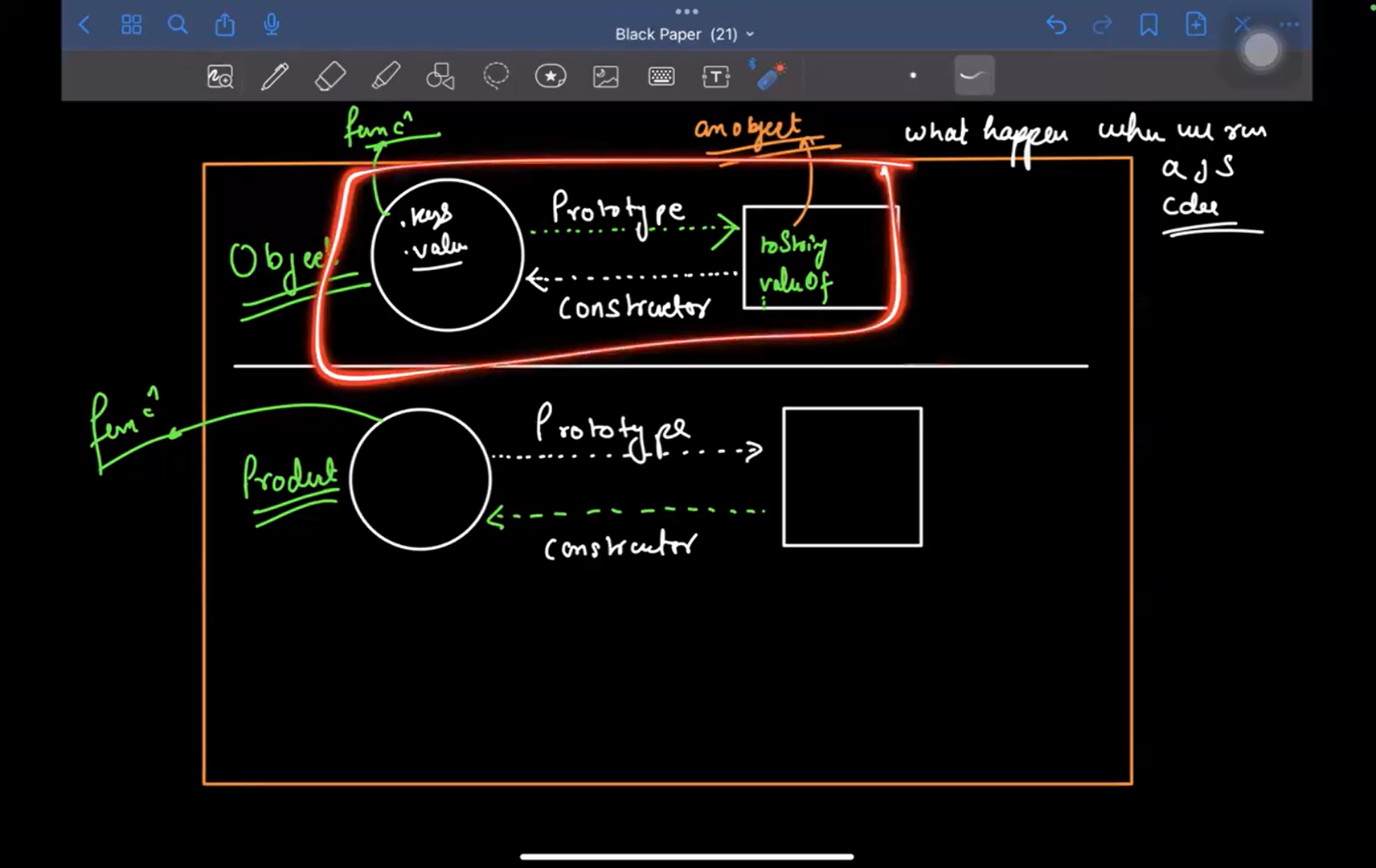

In JS the objects are not based on the blueprints they are technically linked to the blueprint. What is this linking then? And what happens when we run a JS code? -> When we try to run a JS code a lot of thing ofcourse happens a lexical scope gets created and all that. But there is one more thing that happens before the first line of code actually gets executed and this particular is extremely important w.r.t How classes and objects works in JS. Now we will take a deep dive and try to understand what is this and what it does with overall architecture of Javascript.

-

A lot of time we might have seen capital "O"bject.

-

Js maintains a function that we already know as "O"bject this function provide us a lot of feature for example

Object.keysObject.valuesall of these are directly provided to us by this coresponding function, apart from this there is one moreobjectand this is one of the most importantobjectin the whole architecture of JS. Some very important utility function such astoString,valueOfall of these function that we never declared for our own object but we are able to invoke in an object are actually present in this object so what's the name of this object, in JS there's no specific name given to this object but we can refer to this object via a property on the 'O'bject that is known asprototype. -

When we do

object.prototypethen we are referening from theObjectand there is a reverse chaining also that fromobjectactually we have a property that refers back toObjectfunction and that property is known asconstructor. -

Repeating what I just understood: Before the code starts executing there is a function named as capital "O"bject. We can actually call it as function it returns brand new plain object. And this functions has some properties such as

.keys.valuesetc together with all these properties it has one more property as.prototype. This.prototypeactually points to another JSobjectbecause this JSobjecthas all the functions/properties liketoString,valueOfand all those functions/properties that are available on an object but we never wrote it ourselves. On thisobjectwe have one more property/function named asconstructorsame as toString and valueOf that actually points back to the original "O"bject

- Few question might arise

- why we are doing the reverse chaining that from "Object" we are refering to prototype and from prototype we are refering to constructor.

- What is the use of prototype? Why we are using it and need it? Why this 'O'bject is pointing to the prototype? And what is a prototype chaining

function Product(n,p){

this.name = n,

this.price = p

}What is a Product here? It's technically a function

Product ⏎

f Product(n,p){

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

}Now, if we do Product. we start seeing a bunch of properties that we can actually call and one of the properties is named as prototype

- So, we created a new function product and on this product function we have property called

.prototypeand if we carefully see what.prototypeis giving us, it giving us another object

Product.prototype ⏎

{constructor: f}- That means the moment we create a function product along with that function there is an object that gets created. And we refer this object using

.prototype. And if we carefully see from this object also there's an property constructor that goes fromProduct.prototypeto point to Product. So if we doProduct.prototype.constructorit's refering back to the function Product

Product.prototype.constructor ⏎

f Product(n,p){

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

}- A similar setup that exist with "O"bject exist here.

-

Before our code executing there's a capital "O"bject function on this function there are bunch of properties. One of the properties is

Object.prototypethat points to anotherobjecton thisobjectthere are some of the most important properties exist, thisobjecthas a propertyconstructorwhich points back to the "O"bject. This was the pre-setup -

Post setup when we start executing our code, let's say we wrote a function Product, in the function Product we have property prototype which is again pointng to an object and this object has a property constructor which is pointing back to product.

-

With any function that we are having we will have the same functionality actually going on behind the scenes . All of these will start making sense because all of these used to be the actual regular part of JS code before the intervention of class based wrappers . So we will understand

How constructor and everything works? -

What's the meaning of the word prototype in plain english? It refers to the word model or design, So using this we will actually prepare blueprints a models and lot of stuff everything we are doing with classes we will be able to do with this

-

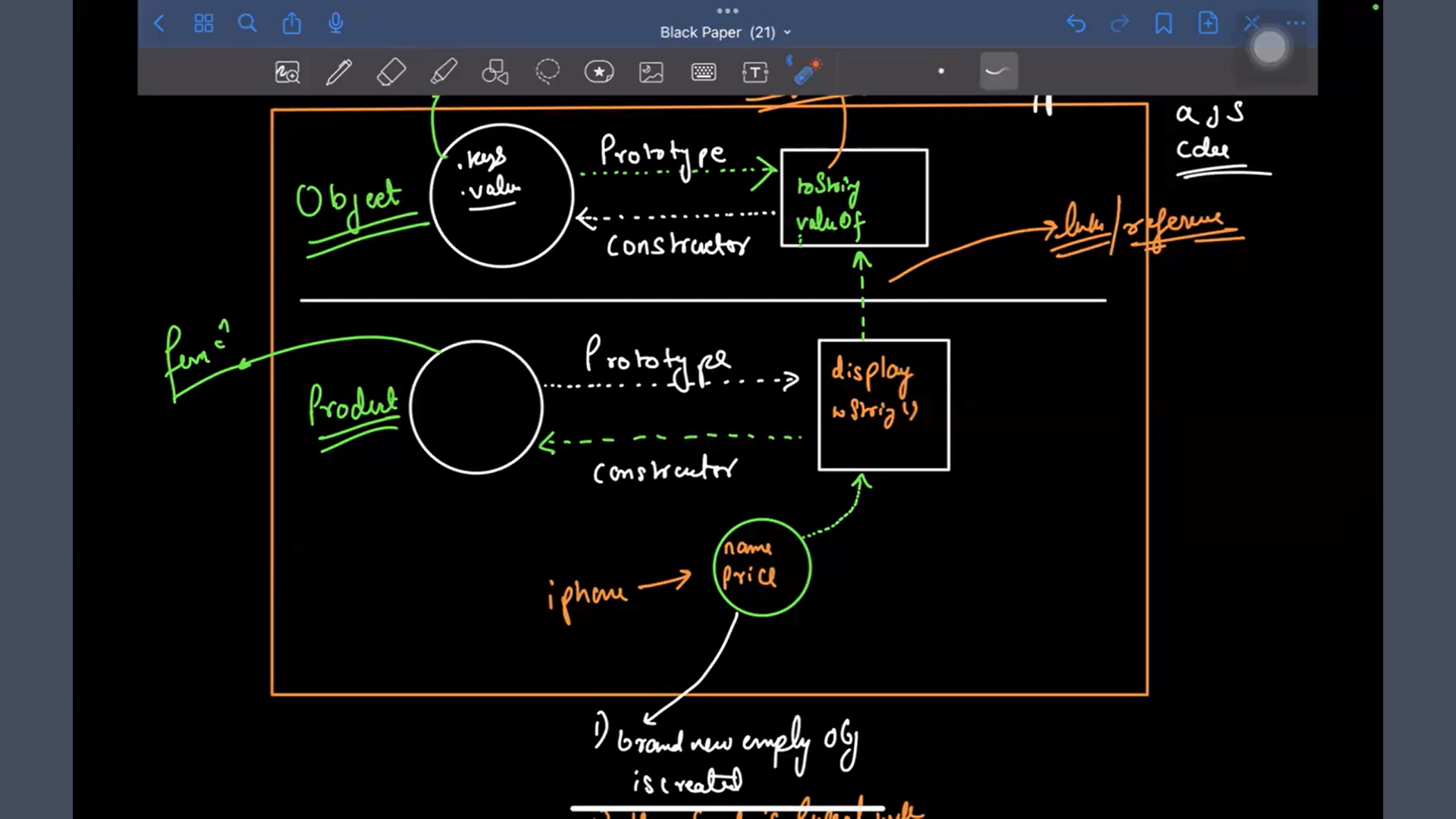

Product.prototype is actually internally linked/referenced with Object.prototype.

-

We have the function Product, now if we do:

const iPhone = new Product("iPhone 14", 1000000) ⏎So we know that when we call the new keyword a brand new plain empty object is created and then we are technically calling the product function. But behind the scenes something more happens.

- The moment we hit

new(Step 1) It creates a brand new empty object (Step 2) Before anything else happens this object is actually linked withProduct.prototype(Step 3) We assign athiskeyword which refers to the call site(the brand new empty object is the call site). And then we start executing the function Product which says this.name and this.price . So we assign a name property and a price property.

Atlast if we haven't manually returned another object from the function Product, JS will assume that we wanted to return ("iPhone 14", 1000000), and this object gets returned and stored in the variable iPhone.

So, the step 2 is the crux of whatever we were doing.

-

Sanket talked about the product function to be constructor. Now just think on the brand new empty object we link this with Product.prototype and we try to call the constructor Product with respect to the iPhone object . Now the iphone doesn't have its own constructor but this object is linked to another object which has a property constructor that is refering to our product function and this is where things start becoming interesting and we will see How all of this linkage is actually going to help us

-

If we do

Product.prototype.display = function (){

console.log("Details of the product are", this )

} ⏎What we have done is on our Product.prototype we have assigned a new function display. If we do

iPhone.display()⏎

// Details of the product are

// > product {name: 'Iphone 14', price: '1000000'}So what is going on? -> During runtime we come to our object, if we say iPhone.xyz() what will happen is, JS will check does your object iPhine has property xyz the answer is NO. So, what it will do is it will go one step above in the prototypal chain and see does Product.prototype has the display property, YES it has the display property/function and now it'll call it.

- So, we made changes to our prototype and those changes are actually reflecting in the object and that is why if we do something like

iPhone.toString()we get[Object object]

iPhone.toString()⏎

// [Object object]Just think about it do we have toString property in iPhone obejct? NO, we go one level up Do we have toString property in Product.prototype ? NO, we go one level up Does Object.prototype has toString property? YES, and that's where the toString function comes up.

-

This is the essence of how exactly

prototypal chainingworks. Your obejct is chained to a prototype that is chained to another prototype and so on... -

Now let's say we make a class Product{} and put a constructor(){}

class Product{

constructor(n,p){

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

}

}⏎

// If we see Product

Product⏎

class Product{

constructor(n,p){

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

}

}

Product.prototype ⏎

{constructor: ƒ}

Product.prototype.constructor ⏎

class Product{

constructor(n,p){

this.name = n;

this.price = p;

}

}If we see product, its returing a class and if we do Product.prototype, its refering to a object and that object has a constructor property that's refering back to our class. So if we see it's the same architecture here, that's why we say that classes are just the wrapper over what we have as functions it doesn't change a lot of things.

-

When we see [[Prototype]] that is actually refering to the prototype object we are kind of linked to, to programatically access the prototype we can do something like

__proto__ -

__proto__: also known as Dunder proto is a property of Object.prototype and it dynamically resolves what is the prototype chaining of the calling context . If we do iPhone.proto it'll refer to product.prototype, so how does it determine that whatiPhone.__proto__should point to being a property of Object.prototype.

This proto invokes a function internally and it'll check which object is the calling context, for this example iPhone is the calling context so it dynamically resolves who is the prototype of iPhone

-

We can use this architecture to do a lot of inheritance things

-

Let's say we have class A and class B, and if we want to do inheritance in JS we can technically say class B extends A{} also create a new object b

class A {} ⏎

class B extends A{} ⏎

b = new B();

// b points to prototype A and is pointing to prototype of Objectthat is why let's say we have class Category and constructor(c){this.categoryname = c;} and we have class Product that extends Category also has a constructor(n,c) and we say this.name = n, we can have super keyword as super(c) to actually pass c to the super class. Now if we create a new object p lets see what happens

class Category {

constructor(c){

this.categoryname = c;

}

} ⏎

class Product extends Category{

constructor(n,c){

super(c);

this.name = n;

}

} ⏎

p = new Product('iPhone', 'mobiles');

// Product {categoryname: 'mobiles', name: 'iPhone'}p has a property categoryname and how is it coming, its because we called the super keyword, super refers to the same class mentioned by the prototype (Category)

-

So, technically bts when we do class B extends A its actually doing nothing but creating some kind of prototypal chaining

-

We can do the same thing using functions as well

function A {

} ⏎

function B {

} ⏎

// if we do ---

new A(); ⏎

// the prototype of A is directly Object.prototype

new B(); ⏎

// the prototype of B is directly Object.prototype

// If we do

Object.setPrototypeOf(A.prototype, B.prototype)

// and now

X = new A()

X ⏎

// Technically pointing to B's prototype, as A is pointing to B's prototypeThis is how we can create inheritance directly using functions, and this is how things starts shaping up and this is something we always should keep in mind that internally when we do extends it's not actually just creating a copy of inheritant stuff but instead if the base classes or the base functions makes any changes the changes will reflect in your corresponding new object as well and that's how Inheritance with JS works. One more simple thing we can see our prototype at one point can point to another prototype so we can have multilevel inheritance, not multiple inheritance