This project is currently on hiatus.

These will be my notes as I learn Reflex, intended to help other people take the plunge. Reflex is a suite of Haskell libraries and tools that enables a wonderful way to do functional reactive programming, or FRP, by applying the declarative nature of Haskell to user interfaces that run efficiently in the browser (with the GHCJS compiler) or as native applications (using GTK).

First, if you haven't, install the Reflex Platform. Let's enter a Nix shell with access to all the things we'll need.

From the reflex-platform directory, type

$ ./try-reflex

If you have any trouble with this script, please submit an issue at https://github.com/reflex-frp/reflex-platform/issues

Entering the reflex sandbox...

You are now in a shell with access to the Reflex functional reactive programming engine.

<snip>

Or to see a more complex GUI example (based on the source at https://github.com/reflex-frp/reflex-todomvc/blob/master/src/Main.hs), navigate your browser to file:///nix/store/mp8dpmfly8wxd03azp37sm5j2shwmsry-reflex-todomvc-0.1/bin/reflex-todomvc.jsexe/index.html

You should have output similar to mine.

For now, create a directory somewhere that you'll use to work on this tutorial. I recommend this:

$ cd ..

$ mkdir learn-reflex

$ cd learn-reflex

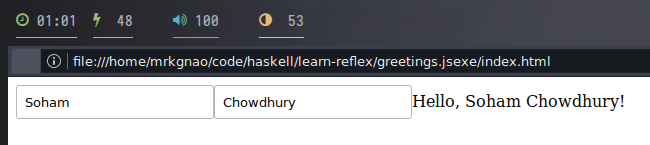

Let's build a little cough webapp that asks the user for their first and last names and displays a simple greeting to them. This is, to me, akin to a "Hello, world!" for functional reactive programming.

Put the following code in a file, which I'll name greetings.hs:

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

{-# LANGUAGE GADTs #-}

import Reflex

import Reflex.Dom

main :: IO ()

main = mainWidget (el "div" ui)

ui :: (DomBuilderSpace m ~ GhcjsDomSpace, DomBuilder t m, PostBuild t m) => m ()

ui = do

fname <- textInput def

lname <- textInput def

let name = mconcat [ constDyn "Hello, "

, _textInput_value fname

, constDyn " "

, _textInput_value lname

, constDyn "!"

]

dynText nameWe'll use ghcjs to compile this. Run

[nix-shell:~/code/haskell/learn-reflex]$ ghcjs --make greetings.hs

[1 of 1] Compiling Main ( greetings.hs, greetings.js_o )

Linking greetings.jsexe (Main)

GHCJS compiles the Haskell code to a JavaScript file. It also creates an index.html file that loads the generated JavaScript: open greetings.jsexe/index.html in a browser!

There's ... still a lot of work to do design-wise, but let's first try to understand the big chunk of code you just pasted into some editor and built.

There are many implementations of FRP, but all of them are based on the observation that applications that react to user input (reactive applications) can be broken into interacting pieces that fall into one of the following two categories:

-

events that fire once in a while: keypresses, doors opening, changes in device orientation

-

behaviors or variables that always have some possibly changing value: mouse position, the current time, health points

and games or user interfaces can be described very succinctly (and, as it turns out, efficiently) in terms of these primitive notions, and by specifying how they depend on each other.

Functional reactive programming, then, is the practice of specifying these dependencies declaratively, instead of writing code that explicitly waits for changes and modifies something in response to the change. For example, one can create an event from a behavior b that fires whenever the value of b changes.

Another example is that of combining two behaviors a and b into a new behavior c with some "combining function" f. The new behavior c, at any time, has a value defined to be that obtained by combining the values of a and b at that time using f. This is akin to the following well-known Haskell function:

zipWith :: (a -> b -> c) -> [a] -> [b] -> [c]For example, given behaviors playerAPoints and playerBPoints corresponding to the scores of players A and B in some game, one might write a function to find if player A is leading, or to find if the game is tied:

isPlayerALeading, isGameTied :: Behavior Bool

isPlayerALeading = zipBehaviorsWith (>) playerAPoints playerBPoints

isGameTied = zipBehaviorsWith (==) playerAPoints playerBPointsReflex represents behaviors that have a value of type a at any given time by its Behavior t a type, and events of the corresponding type by Event t a. (I'll explain where the weird t type parameter comes from in a moment.) Another abstraction Reflex provides is the Dynamic t a type, which is essentially a Behavior t a and an Event t a rolled into one such that the event fires whenever the value of the behavior changes, so you can both ask for the value of a Dynamic or ask to be notified when it changes.

The t parameter is supposed to refer to a "timeline", and users of Reflex should (apparently) write timeline-independent code. I'm guessing that when Reflex code is run, the t parameter is swallowed up by a forall in a similar way to how the ST monad works.

Let's explore the functions we used in our example in GHCi. Note that we can use the familiar GHC tools here instead of mucking about with GHCJS --- Reflex works just as well in either case.

[nix-shell:~/code/haskell/learn-reflex]$ ghc --interactive

GHCi, version 8.0.2: http://www.haskell.org/ghc/ :? for help

Prelude> :m +Reflex Reflex.Dom

Prelude Reflex Reflex.Dom> :t textInput

textInput

:: (DomBuilderSpace m ~ GhcjsDomSpace, DomBuilder t m,

PostBuild t m) =>

TextInputConfig t -> m (TextInput t)Huh, so after being given a TextInputConfig, it renders a text input to the screen and returns an associated TextInput value in whatever monad we're in. We used def: TextInputConfig has an instance of the Default class, which is roughly of the form

class Default a where

def :: aThis makes sense, since we ordered two plain textboxes, fname and lname, no-extra-toppings-please-thank-you-very-much.

And what's inside that TextInput?

Prelude Reflex Reflex.Dom> :i TextInput

data TextInput t

= TextInput {_textInput_value :: Dynamic t Text,

_textInput_input :: Event t Text,

_textInput_keypress :: Event t Word,

_textInput_keydown :: Event t Word,

_textInput_keyup :: Event t Word,

_textInput_hasFocus :: Dynamic t Bool,

_textInput_builderElement :: InputElement

EventResult GhcjsDomSpace t}

-- Defined in ‘Reflex.Dom.Widget.Input’Aha! It seems that a TextInput wraps a bunch of those cool FRP things I was talking about. In particular, we have Events corresponding to key events on the input field, and a Dynamic value corresponding to what's in it. And this type is a plain record, so the use of _textInput_value was just to get at this Dynamic, which happens to have a Text value at each instant.

The next piece of the puzzle is the mconcat. It seems Dynamic t a has a Monoid instance if a does, which should make sense if you recall our discussion of "zipping" behaviors together from above. At any instant, given a list (or, rather, any Foldable) of Dynamics, we can make a new one whose value at any instant is given by mconcat-ing the values of the elements of the list at that instant.

So our test code would be something along the lines of

mconcat [ "Hello", _textInput_value fname, " ", _textInput_value lname, "!" ]except that won't typecheck because the _textInput_values have type Dynamic t Text, not just Text. We can fix that: just make a Dynamic that always has the same value, sort of like the familiar const function:

const a _ = aThis is achieved with the constDyn function, which does exactly what we asked for. With that, we're almost there: we now have a Dynamic t Text that contains a greeting built from the user's name. We now need to display it, so we turn to dynText:

Prelude Reflex Reflex.Dom> :t dynText

dynText

:: (DomBuilder t m, PostBuild t m) =>

Dynamic t Text -> m ()This takes a dynamic Text value and just displays it to the screen as a label, which happens to be the last piece of the puzzle!

You may have noticed that the type of constDyn is a specialization of pure:

constDyn :: a -> Dynamic t a

pure :: (Applicative f) => a -> f aIn fact, Dynamic t is an Applicative and constDyn is its pure function!

Exercise. Replace constDyn with pure in the original code listing and compile it again. Verify that nothing breaks.

The ugly type signature on ui can be inferred, but only if you turn off GHC's -XMonomorphismRestriction flag, which is enabled by default and prevents GHC from inferring polymorphic signatures for top-level bindings (hence a monomorphism restriction, one which forbids polymorphism). This means that a binding such as x = 1 at the top level of a Haskell file will, by default, be inferred to have the type x :: Int, instead of x :: Num a => a.

To do so, we add a language pragma at the top of the file that turns that flag off. With that in place, the code compiles fine without the type signature:

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

{-# LANGUAGE GADTs #-}

{-# LANGUAGE NoMonomorphismRestriction #-}

import Reflex

import Reflex.Dom

main :: IO ()

main = mainWidget (el "div" ui)

-- ui :: (DomBuilderSpace m ~ GhcjsDomSpace, DomBuilder t m, PostBuild t m) => m ()

ui = do

fname <- textInput def

lname <- textInput def

let name = mconcat [ constDyn "Hello, "

, _textInput_value fname

, constDyn " "

, _textInput_value lname

, constDyn "!"

]

dynText name