aka The Vanifesto

===========

This repo is an ongoing project designed to facilitate a course I teach in iOS development.

The goal is to provide a broad reference to Swift language syntax for students new to the language and then focus in sharply on the parts of the language that make use of functional programming techniques.

It is my observation that Swift as a language has three parts:

-

a relatively small kernel of syntax and functionality that centers around Swift's powerful type system and makes use of contemporary functional programming patterns.

-

a larger set of syntax that is built on the kernel and which adds useful syntactic sugar curated from a variety of other languages to the tastes of the Swift core team at Apple.

-

A layer of features which exists to provide backwards compatibility to C, Objective C, and even Python. This portion of the language makes use of standard, single inheritance, pointer-based, object-oriented programming techniques.

Given the state of Apple's platform in 2010 when Swift development began, the backwards compatibility layer inescapably had to be developed and completed first and Apple had to engage in a lengthy and laborious process of converting programmers to the new platform. As I write in early 2020, most of the Apple development community has moved to the new platform with only a few laggards remaining, but much of the community still writes its code using the OO syntactic elements and is not yet fully up to speed with functional kernel.

I believe that Swift 6, Combine and SwiftUI represent an inflection point where the community as a whole will begin transitioning from the OO paradigm and begin making full use of the smaller syntactic core. The ultimate goal of this repository is to help my students move in that direction and prepare them for the shift I see underway in the Swift community.

NB All code in this project is in commented playgrounds using Apple's Markdown comment formatting specification. So you'll want to do the following in Xcode: Editor->Show Raw Markup whenever you open a playground.

One final note: I highly recommend reading or watching pretty much everything in the bibliography attached at the bottom of this document.

It is impossible in a single work such as this to cover everything in the detail that it deserves, so I've incorporated pointers to things that I particularly liked and found helpful in the bibliography. In particular, I cannot recommend the Pointfree video series highly enough. I link below to their free content, but I pay them for a subscription and I recommend doing the same to anyone serious about functional programming in Swift.

Additionally, I keep A Companion for SwiftUI open on my desktop as I work pretty much continuously and it is another tool I strongly recommend.

learn-swift comes originally from Paul Nettle's learn-swift repo. Playgrounds 1 - 23 are his original work and were created using Swift version 1 by working his way through the "Language Guide" section of Apple's book, "The Swift Programming Language".

Revised markdown formatting in all playgrounds, updates to Swift versions >= 4, and Sections > 23 are by Van Simmons.

Programmers familiar with other, primarily OO languages who are new to Swift.

You will need XCode 11.4 (or later) and a Mac to run it on.

Going back to the notion of the language having three parts, I think we can assign some syntactic weights to them:

-

the kernel: call this 10% of the language.

-

the syntactic sugar layer: I typically talk about this as being another 20% of the language.

-

the backwards compatibility layer: I would argue that this comprises about 70% of the language.

These weights of course are subjective and I provide them only to make another point. What frequently confuses people coming to Swift from other OO languages is that they feel that, because they know and are familiar with the large portions of the 70% and they can use portions of the 20% fairly quickly, they then feel that they "know" the language. This happened to me. And I was wrong.

This workspace covers the 70% and portions of the 20% in Playgrounds 1-25. Knowing all of this syntax is necessary in order read Swift, but it doesn't guide you in how to write it. Playground 26 forward does that.

It has taken about 6 years of working with the language on a daily basis for me to see the language in this 70/20/10 light. Seeing it this way has completely changed my approach to the language and my style of using and teaching it. These playgrounds are an adaptation of that style.

I used to start this class off with the following warning:

THINGS IN SWIFT THAT EVERYONE HAS PROBLEMS WITH

- Special Syntax

- The Type System

- Closures, and in particular "trailing closure syntax"

- Generics

- Optionals

- map/reduce/zip

- value types and reference types

When teaching the type system, I would make everyone memorize the fundamental elements of the Swift type system: function, tuple, struct, enum, class, protocol because I felt the type system was idiosyncratic and that rote memorization was the only way you could learn it.

Now I know that the reason its hard is because my teaching sucked. The point of these playgrounds is to suck less.

The secret to life is setting expectations correctly.

(BTW, you will still have to learn all six elements of the type system. My hope is that they don't seem like idiosyncratically chosen random bits and pieces glued in from C and ObjC after this).

If you look carefully at the list above, you will see that it all relates to the type system. If you really want to understand Swift at an advanced level, that's where you will focus. Playgrounds 26 forward take a specific path through the type system with an emphasis on creating an understandable taxonomy. Others may or may not find this useful, but I have found that it gives students an epistemic framework which lets them deal with the system piece by piece.

Be familiar with:

- Apple's API design guide recommendations: https://swift.org/documentation/api-design-guidelines/

- Ray Wenderlich's style guide: https://www.raywenderlich.com/809-swift-style-guide-updated-for-swift-3

- In particular, since this always comes up, you will want to be familiar with the Apple's swift-format tool (https://github.com/apple/swift-format) and just follow the default formatting it provides since a) that's what the whole world will be doing and b) it will be what Xcode wants to do naturally and c) Xcode provides many handy code manipulation features which you can't use if you vary off of these much. The rectangular selection/entry and error messages around type signatures and positioning of popup error messages are the big things here.

With the advent of Xcode 12 in autumn of 2020 this becomes much less important for the programmer because it is much more automated, but its still useful to know so that programmers new to the language do not try to retrofit styles from other languages onto Swift.

You will want to pay special attention to familiarizing yourself with the following concepts that are specific to Swift and similar languages (Rust and Haskell for example) and that are absent or different in various ways from Java/JavaScript/ObjC:

Current Swift features:

- Types expressible as either value or reference types

- Sum types (enums) and Exponential types (functions) captured as first-class types in addition to Product types (structs and classes)

- Strongly typed, reified, constrained generics

- Simplified syntax for functional composition techniques

- Structural types as well as nominal types

- Strong type inference when using structural types

Coming Swift features:

- Direct language support of Rust-style memory ownership

- Direct language support of concurrency constructs. My own belief here is that Swift is going to adopt an Actor model for concurrency. See below in the section on Functional Reactive Programming for how this fits into the overall architectural of an app.

See below for more details on these and several other FP (functional programming)-related features.

The community is converging on using the functional programming aspects of Swift and deprecating the imperative programming parts. At this point it is clear that many of the imperative features of the language are there to smooth the transition from ObjC to Swift. These features remain in the language, but best practice is to use them more and more sparingly, if at all. Because of this (and often surprisingly to those familiar only with the imperative style), best practice is to avoid the following features of Swift:

- for-loops - use Sequence higher-order methods instead

- while-loops outside of

RunLoops- use trampolines instead. - callbacks, delegates,

NotificationCenters, or similar constructions - you should replace these with use of Combine Publisher(s) in every case - inheritance - replace with a mix of generic wrappers, enums, protocols and protocol witnesses as appropriate,

- the

throwskeyword in APIs that you design - you should use Result instead.throw-ing functions simply do not compose well and hence do not fit well inside a functional code base.

- functions that return or accept

Void- Void-returning (or accepting) functions, by construction, can only be used to accomplish side-effects. The type system has specific capabilities to handle side-effects in more efficient functional ways, so Void-returning functions should be avoided. E.g. if you return Void because you are dispatching an asynchronous operation, you should look at Combine or SwiftNIO and return a Future instead, if you are returning Void from a setter, you should consider the functional alternatives that allow chained application or, even better, move to using immutable objects that are constructed correctly to begin with. (For brevity, I'll refer to functions which return or accept Void henceforward as "Void-returning".) Array.forEach-forEachis used to perform Void-returning functions on Sequence types. It is itself a Void-returning function and therefore falls under the guideline of things to avoid for both what it does and what it returns. This should be avoided except for instances of interacting with imperative code.PassthroughSubjectfrom Combine. You use PassthroughSubject in order to invoke itssendfunction, which is a Void-returning function and therefore indicative of an imperative-only interface. In a pure functional codebase this is not needed. It is there to connect the imperative and functional parts of your codebase.

- Protocols. Protocols should be thought of as somewhat equivalent to

finalin inheritance-based systems. Because you can only conform any given type to a protocol in one way, you should verify that anything implemented as a protocol is actually the unique implementation for all conforming types. Most application-level declarations of protocols do not meet this test and should use protocol witness structs instead. So, for example, Hashable and Equatable can be implemented only one way for any given type and are therefore good subjects for protocols. CustomDebugStringConvertible frequently can be implemented in multiple ways for a given type and in those circumstances should be managed with a protocol witness rather than a conformance. You should think about this when you go to create a protocol type and by default use a witness type instead unless you can verify the uniqueness requirement for the implementation. - PATs (Protocols with Associated Types) should be reserved as a feature for people writing framework libraries. This is a very complicated area of the language, that as currently constituted, does not have a simple UX. PATs should be reserved for very specific cases where the programmer truly understands the interactions of the various concrete types being designed. The only exception to this may be protocols which have only an associatedtype of Self. If you are planning to make use of PATs you may well want to do some reading on type and category theory to make sure you understand the thinking that has already gone into standard library protocols like Sequence so that you avoid reinventing wheels.

- the

mutatingkeyword on structs. This should be used only as a performance optimization after it has been proven to be to necessary. It is frequently associated with functions returning Void. The deprecated pattern is to create avarstruct or class and then immediately begin mutating its values to properly configure it. Usage of this pattern should always be replaced with inits which construct the value correctly to begin with. Inits of this type frequently take closures so you'll want to be aware of how to use closures in your initializers. varproperties in structs. By default your data structures should be immutable and mutability should only be used after due consideration and a driving performance requirement. If you make your propertiesletby default, you will find that use of the mutating keyword in the previous point simply goes away on its own.

- trailing closure syntax if using Swift versions greater than 5.2. With the introduction of the ability to use Keypaths in all places that closures can be used and the

callAsFunctionfeature, many uses of inline closure declarations are no longer needed and can be replaced with a more "point-free" style. ifandif-elsestatements (prefer the use of ternary conditionals that return values instead), Ifswitchhad a language-supported form which returned values in the way that ternary if's do, switch would join this list.

Note that some of the points above are not iron-clad rules but others are. For-loops, callbacks and inheritance are never needed and should not be used. Void-returning functions and PATs are appropriate in some specific but infrequent situations. Ternaries over if's and protocol witnesses can be aspirational. However, all uses of the above should be carefully considered before they are employed in code.

If you adopt the points above, you will find that you can adapt to Swift's natural style much more quickly.

Swift is classified as a hybrid OO-functional language, but it is clear that its design anticipates applications moving from OO to a more functional style. The following features bear directly on that transition and are things that someone coming from OO languages should pay close attention to understanding.

- Value types are first class objects. In many OOP languages (Java, JavaScript, ObjC, Python) only reference types can be objects. In Swift, all structs, classes, enums and protocols are objects. This has important performance and memory implications especially in server side or multi-threaded code. This is possible because underneath the covers Swift views all 'objects' as data types with associated static functions and this fact itself can be leveraged in many interesting ways.

- Extensibility of all Types. Because of the way the type system is implemented, every type can be extended - including things like Int and CGRect.

- Sum Types. Swift's type system includes Sum types (enums) as well as Product types (structs and classes). Many OOP type systems such as C++, Java (for now) and ObjC (for always) lack Sum types (except in a very primitive form built on C's int type). Both Sum and Product types are required for any system of Algebraic Data Types (ADT's). Enums allow succinct formulations of algorithms that require very clumsy circumlocutions in languages without sum types.

- Reified generics. In Swift, generic types are not simply hints to the compiler, but are real types subject to rigorous type checking. The difference is that instead of typing the code for a given generic type yourself, the compiler generates (aka reifies) the type for you. Swift's generics are best thought of as functions on types which are called at compile time rather than at run time. There's a lot of generic enhancement still to come in future versions of Swift so it is important to be aware of changes in the system.

- Type Inference. Swift provides type inference mechanisms built on Algebraic Data Types and reified generics that make it possible to write type safe code that would be extremely difficult to write or subsequently read in C-based languages.

- Function composition. The features above, taken together, allow Swift to provide syntax and semantics for forms of functional composition which simply are not available in ObjC or Java (Javascript actually does much better at this). This is probably the hardest feature for OO programmers to grasp. In OO languages, you can pass a function to another function or invoke a function - but the syntax for writing a function or method to take other functions or methods as arguments, compose them in some manner and return the composition is (charitably put) unwieldy to use. So it very rarely is. Fundamentally, it is composition of this sort (taking/returning other functions with strict type checking, aka "higher order functions") which differentiates functional programming from OOP. (See the John Hughes paper in the bibliography below).

- Ownership model. Swift has a much more sophisticated ownership model for reference types than ObjC. Think of it as ARC++ that can be enabled because the syntax of Swift can be extended to support it. The OSSA improvements to the SIL mentioned in the bibliography are key here.

- Using Swift's functional composition capabilities allows one to use functional decomposition as the basis for refining an application into smaller more understandable parts.

- One of my favorite quotes from the John Hughes article linked below: "Our ability to de- compose a problem into parts depends directly on our ability to glue solutions together. To support modular programming, a language must provide good glue. Functional programming languages provide two new kinds of glue -- higher-order functions and lazy evaluation."

- A key insight of the functional style is that all programs can be decomposed into the application of functions, some higher order, some not.

- While Swift does not do lazy evaluation, it does handle higher order functions quite well.

Application architecture in the Functional Reactive Programming (FRP) style broadens functional decomposition to allow interaction with asynchronous streams of events. FRP is inherently about reacting to events as they arrive (in JavaScript, the most common framework used for this architecture is even called React). Since, by nature, events arrive asynchronously, FRP can be viewed as an attempt to tame asynchrony.

- In Swift, FRP is embodied in the Combine framework.

- Under FRP you should think of your application as being a collection of functions which are nested in one or more long-running event loops

- On Apple platforms, registering to receive the dispatch of the event happens in many different ways, some implicit, others explicit. Each library does this differently.

- In this model, ApplicationState is an immutable value wrapped by a singleton reference type that moves over time from one value to the next.

- Technically speaking there are a couple of layers between the entry of the event and function dispatch under SwiftUI or SwiftNIO, but from a conceptual standpoint, this is the correct idealized model.

- Also, technically, the ApplicationState can be mutable if sufficient thought and care are given to managing mutation, however, frequently this is neither desirable nor necessary.

This point about application state and how it changes over time is the architectural crux of all application development in SwiftUI and SwiftNIO. Let's explain what that means.

The functional reactive programming (FRP) style as embodied in Combine takes functional decomposition into the asynchronous domain of handling events. Under FRP you should think of your application as being a collection of functions which are nested in an event loop or loops. In GUI apps that's typically the event loop of the main thread, in server apps, it's the event loop of a worker thread.

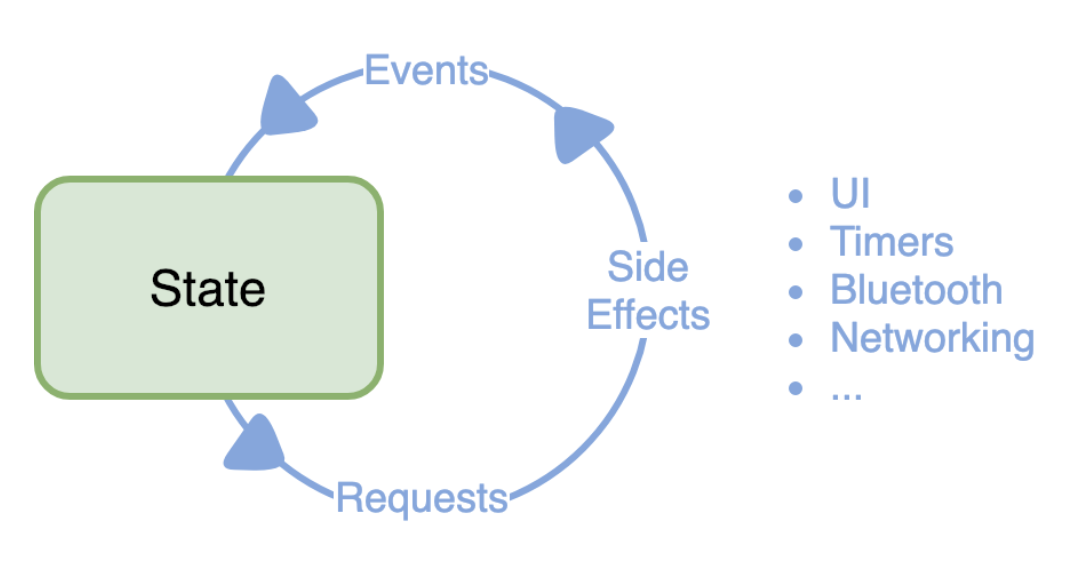

When an event enters the event loop, a function is selected to dispatch the event into. That function is called by passing in 1) the current state of the application AND 2) the new event. The function returns 3) a tuple composed of the new state of the application and 4) any side-effects to be performed. In this model, ApplicationState is an immutable value type wrapped in a mutable reference type which is tracks changes of AppState over time. The old value type is replaced at the end of the event loop by the new value computed by the function the event was dispatched into and any accumulated side-effects are dispatched.

Wrt to side-effects: in this model, side-effects are "pushed to the edge of the world" by cumulating them and executing them at the bottom of the event loop after execution of the event-handling function. Side-effects can generate new events, which enter the queue of events to be processed. Some types of side-effects that you can think of include: updating the display, firing a network request, and starting a timer.

This model is precisely the one used by SwiftUI. Display update is a direct side-effect of updating ApplicationState implemented as part of the SwiftUI framework. SwiftUI's Views are not mutable for this reason. They are generated using a particular value of the Application State to which they are connected by property wrappers of various forms.

The above ineluctably implies that long-running applications should be organized as collections of functions of the form:

(ApplicationState, Event)->(ApplicationState, [Effect<Action>])

(In Swift terms, the array of effects is actually replaced by a Publisher). In functional programming terms, functions with this signature are called reducers. Your application should decompose this function into a chain of function invocations mediated by the type system. If you are working with a mutable ApplicationState, this signature is

(&ApplicationState, Event)->[Effect<Action>]

The equivalent form of this latter function in OO notation is:

applicationState.handle(anEvent)->[Effect<Action>]

where the applicationState is mutated by the event handling method call.

The unconstrained creation of side-effects arising from the introduction of mutation by the OOP style is a critical difference between the two approaches. This difference explains why you don't want to return Void during your function application. Returning Void anywhere in this chain is a clear signal that you have introduced a side-effect that is not being pushed to the edge of the world and it breaks the flow of the function invocation chain, to boot.

Chaining on the return type of Void means that the type system cannot help you reason about the handling of an event or assist in managing side-effects. Allowing the type system to help is one of the main appeals of the FRP style and properly done can greatly improve programmer productivity.

Side Note: one way of looking at the imperative style is to observe that every statement is a Void-returning function call and that even when programming imperatively, the functional model still covers things. It's just that the ability of the type system to assist in writing the program has been discarded.

The FRB style is so different from the traditional UIKit MVC model that it can be disorienting at first. A good diagram of what this style looks like can be found here. This is a nice graphic drawn from that location.

FRP-based applications should be thought of as following this model with State being divided into many intercommunicating substates. This point is very important. None of the discussion above implies at all that there should be only a single global state available to the application. Most large UIKit applications end up with such a single global type (frequently signalled by a name that includes the word Context), but this is an anti-pattern in SwiftUI.

Under the FRP architecture, the State shown in the diagram above becomes a tree of smaller State objects with communication allowed only up or down the tree, using Combine. All UI is grouped in modules, each of which can see a particular node on the State tree. So for any given sub-hierarchy of views, the diagram above is correct. What is missing is the communication between sub- and super- States.

This is in fact, where an Actor model of concurrency would fit perfectly. An event would be dispatched into an actor designated to handle it. The event could be processed concurrently with any number of other events all of which would submit their side-effects as Requests back to dispatch actors designated to process them. An actor model is part of the original Groff/Latner Concurrency Manifesto and is probably under consideration for Swift 6.

Swift's type system is discussed below in detail and consists of: tuples, functions, structs, enums, classes, and protocols PLUS generics of the first 5 things in that list (Protocols and generics interact in very weird ways).

If you are coming from an OO background it is frequently the case that you will think the following things when you pick up Swift:

- Classes and protocols look quite familiar to what you are accustomed to in Java or ObjC or JavaScript and should be the first tool you reach for when designing new code, just as they are in those languages.

- Structs seem like classes with several useless limitations

- Functions appear to be just like methods

- Generics seem a bit superfluous given that inheritance is available for classes

- Enums and tuples look like trivial extensions from C

Be aware that each and every one of these perceptions is mistaken in some fundamental way.

Tuples in Swift are called structural types, whilst structs are called nominal types. Here's an example of what this means:

(Int, Int)

(row: Int, col: Int)

(x: Int, y: Int)

are all the same structural type and can be substituted freely for one another - anywhere the type system allows one, it allows the others. OTOH,

struct Location { let row: Int; let col: Int }

struct Coord { let x: Int; let y: Int }

have identical structures, but are completely different nominal types precisely because they have been assigned different names. And one cannot substitute one for the other in any context.

The first example is called structural typing because it depends only on the structure of the type. The second is called nominal typing because it depends only on the name of the type.

You will want to:

- Fully understand when you should use structural types and when you should use nominal types

- Observe in passing that enums have no corresponding nominal type form, though this has been discussed in the community

- Make sure you understand tuple syntax and in particular that tuples can be broken apart into their constituent pieces - this feature is called "destructuring" because it takes a structural type and breaks it apart into nominally-typed components.

- Note that each function in Swift takes exactly only one argument - and somewhat as you would expect - that argument is a tuple (This has not strictly been true at the compiler level since Swift 3, but from an API usage standpoint it is still the case)

-

Functions in Swift are first-class objects, they can be assigned to variables, passed in to other functions as arguments and returned from functions just like any other type.

-

It is important to note that when a function returns a function, the return value is necessarily a composition of some function.

-

Swift syntax provides very powerful tools for composing functions together in ways that are extremely difficult in ObjectiveC, C++ or Java

-

Other languages admit functions as first class objects, too. Swift's contribution has been simply to optimize the syntax in an idiosyncratic way that makes it much easier to do. Accordingly, programming techniques which are built around function composition are used much more often in Swift than in other languages where the syntax is not so optimized.

-

Swift is not the most optimized for this usage, because it still clings syntactically to features from C and ObjC, but its pretty good in this regard.

-

It is the function-creating-function feature that most confuses OO programmers new to Swift. You should think of the various forms of composition as being an API on functions, similar to the API of String or Array. It will be used just that frequently.

-

There are two key syntax elements that are required to use functions as first class objects effectively. These are key to all of the functional programming constructs mentioned below:

- When functions are passed as to other as functions they are passed without arguments, this is how you distinguish a function passed as an argument from one whose return value is passed as the argument. If you meant to pass the return value and instead pass the function, you will see error messages which at first are confusing, but which will seem intuitive once you absorb this distinction.

- You must remember that the

->operator associates to the right. So(X) -> (Y) -> Zis equivalent to the signature(X) -> ((Y) -> Z)and is a function accepting an X as an argument and returning a function which accepts Y and returns Z. This is in contrast to:((X) -> Y) -> Z, which is a function that accepts a function (X) -> Y as an argument and returns a value of Z. - It is crucial to reading Swift code that you understand this difference

-

The right association of the

->operator (i.e. function-accepting-function vs the function-returning-function) distinction is another one of the hardest syntax elements for those new to the language to acquire. Remember that parens are required to force left association if it is needed. -

You can separate any function call which accepts a multi-valued tuple such as

(X, Y, Z) -> Ainto a chain of function calls(X) -> (Y) -> (Z) -> Awhere the original function's input tuple is destructured and all of the calls until the last one simply bind the value passed in and return a function which takes the next type. This process is called currying.curryis a valid function in Swift. -

You can reverse this via a process called uncurrying. uncurry is also a valid swift function.

-

Currying and uncurrying are far more important than you may originally think if you are coming from an OOP background. They illustrate just two of the various function composition techniques available in the language.

-

Anytime you see a signature of a function which is curried and which has no side-effects, you can apply a function which can flip the order of any of the arguments without effecting the final result. This should be as intuitive as changing the order of arguments on any multi-valued function call.

-

flipping and currying a function's arguments to designate one of the function's arguments as THE object being operated on is the entire basis of OOP.

flipis also a valid function in Swift. -

OOP in a functional programming setting is purely a notational device designed to enhance programmer intuition. Any functional program can be written in OOP notation, but this is not always the more intuitive means of expression and should be used judiciously.

-

In regards to the OOP notation, you should understand the following about functions which are 'methods' associated with enums, structs, classes and protocols:

- Each function you think of as an "instance method" on a type A, taking arguments such as X, Y, and Z and returning B is actually just a static function of the form:

(A) -> (X,Y,Z) -> B.- NB, this function takes an

a:Aas an argument and returns a function(X,Y,Z) -> Bas a result. - This is the way in which an object of type A is bound as 'self' to the method.

- This can be compared or contrasted to the technique used in ObjC where the first argument to every method implementation is

self. This syntax reinforces that you must become accustomed to reading function signatures involving multiple->operators. - Each initializer on a type A is just a static function with the name init, taking a tuple value and returning a value of type A

- Each static function on A is just a regular function with the name "A." prepended to its name.

- Combining the previous points with the ability to manipulate function signatures via

curry,uncurryandflip, it becomes clear that everything you might think of as object orientation is just a complicated form of name mangling and argument ordering of functions over data types. - All of this in turn allows 'methods' on objects to be passed and manipulated in the same way that any other function is. This is in contrast to ObjC where IMPL's of methods have a more complicated type signature than the method itself and which are largely hidden from the programmer.

- Don't do unnecessary variable redeclaration in closures, use $0 $1, etc wherever possible, or even better just pass a function and let type inference do its job.

- The main case where you will want to redeclare a variable is when you are using a higher order function inside of a closure passed to another higher order function. But if you find yourself doing that you probably want to be flatMapping it anyway.

- Always try to use trailing closure syntax when possible. Putting parens around your closures is considered unhygienic EXCEPT where multiple closures are being passed into a single function. And in that circumstance you may want to curry the called function so that you can still use trailing closure syntax.

- Use a guideline of a maximum of 5 lines per function/closure. This is not always possible with Swift bc it lacks pattern matching as powerful as some other languages, but it is a very handy standard to say you should look at functions that get longer than 5 lines with a lot of skepticism and consider splitting the function into smaller named pieces.

- Combining small functions with the preference for guard/guard-let and the recommendation above to prefer ternaries over if's means that you will find that your code will have very few

ifandif-letstatements. This is not accidental. - As much as possible, try to make closures you pass into a function NOT be @escaping. The compiler can perform several performance optimizations on non-escaping functions that it can't when the function is @escaping.

- When dealing with asynchronous functions, this is of course, not possible, but its worth looking at every @escaping usage to try to determine if it has been introduced without good reason and can be avoided.

-

Know how to use the basic functional programming operations like

pipe,curry,uncurry,flip,with,composeetc. -

Understand why and where to curry your functions so that you don't break the function chain unnecessarily.

-

Make sure that any functions you write produce types which move the application's decomposition forward

-

Question the use of any functions which return Void, as mentioned above, because it 1) breaks the function invocation chain and 2) introduces unhandled side-effects

- The most common case where this cannot be avoided (until you can use Combine or a similar package) is a function that acts asynchronously.

- The second most common case is setter methods.

- Almost any other returning Void case is incorrect.

- NB that with Futures and Promises available from the Combine framework and SwiftNIO, the async case goes away.

- Setters are addressed through other pure functional techniques).

-

Anywhere you find a Void-returning function, look for the side-effect it produces and think about how to handle it appropriately by wrapping it in a returned generic.

-

Anywhere you find yourself using a function which takes no arguments, you should consider changing the function to be a computed var.

-

If you not familiar with ADTs as a theory, I highly recommend that you watch the Pointfree episode listed in the bibliography.

-

Void and Never

- Be aware that Void is actually a meaningful type in Swift, specifically it is the structural type inhabited by only one value. Incredibly, this has meaning and makes sense of a lot of other things once you really grasp it.

- Understand that Void's syntax is different than other types because the way it is expressed syntacticly,

(), represents both the type and the value for Void and whether it is the type or value being referenced in any given situation is context-dependent. - Understand that Swift's implementation of Void which typealias'es it as a tuple (aka a structural type) has some downsides. Since Void is an empty tuple it is not possible to define extensions on it. You might want to consider emulating Haskell here and defining an equivalent struct (aka a nominal type) called Unit which is the empty struct. This has the advantage of being extensible.

- Also be aware that Never is also actually a meaningful type in Swift, i.e. it is the nominal type inhabited by NO values. This also has meaning especially as a parameter to generic types.

- For reference, Never is defined as the empty enum. (Think about it)

-

Understand that structs are Product types and enums are Sum (or Coproduct) types in Algebraic Data Type (ADT) Theory. If ADTs are not familiar, you may want to spend a little time understanding the difference, it will really improve your design and architecture skills.

-

When designing types, you should consider how to make any classes, structs or enums you create Equatable and Hashable. You may not need it at first, but if it gets exposed to SwiftUI, you almost certainly will have to do this.

-

Understand when value types get copied and when they just get used.

- Corollary to this make sure you understand how and when to use the mutating keyword (which is almost never)

-

Recognize that

classexists to providestructwith a reference type and is to be used only in that manner. It should NEVER be used to provide additional polymorphism to a struct. -

Accordingly, NEVER use inheritance in your own classes, it's just not how things are done in Swift, and contrary to what you probably think, you don't need it. The polymorphism you seek with inheritance is actually available with other techniques.

-

If you think you need a class (and particularly some sort of subclass), almost certainly what you actually need is a generic class that wraps the struct that you really need as its generic type.

-

All classes should be marked as final but can accommodate mutating any wrapped values.

-

If you think you need inheritance, you definitely need a protocol witness and/or a generic wrapper of some sort.

-

Seriously, look at the Swift std library, at SwiftUI, at SwiftNIO, the new Swift Numerics and at Combine. Classes are used only as reference types, inheritance is never used, and every class is marked final to make sure it stays that way.

-

Property wrappers have been added to Swift specifically to assist you in not using inheritance.

-

Classes should be used only to provide a reference type to a struct. (It should be viewed as a shortcoming of the type system that enums don't have a similar "reference typability").

-

By the above, you should use structs wherever possible instead of classes. This can't always be helped, but it usually can.

-

Only use classes when you must have a reference type such as when you need to access an instance in multiple threads, or when you will need to perform post-instantiation mutation.

-

By default, properties of a struct should be let, not var. Always look to see if you can make something a let and set it at init time rather than just making it a var on the chance that you will want to update it.

-

If you find that you have created a class that only has let properties, it should almost certainly be a struct and not a class

-

Corollary to the use of structs by default: avoid the mutating keyword in structs where possible.

-

Immutability is actually a feature, not a bug. if you need mutability you probably need a generic class wrapping the struct and you need an entirely new copy of the struct for each change.

-

If you must mutate try to do so in private methods.

-

Corollary to all of the above you should always use static methods instead of class methods on classes. Since inheritance is deprecated, using a feature that only applies when overriding superclass behavior doesn't make sense. Don't introduce constructs which require inheritance unnecessarily.

- Since you should never use inheritance, you should never derive from NSObject or anything that derives from NSObject

- In practice, the only time you would do this is if you derive from NSObject to fill a roll in a UIKit object, e.g. being a delegate of a UIKit class.

- This use will die away as applications migrate from UIKit to SwiftUI (which, however fast you think this might be, will probably be faster)

- Deriving from NSObject breaks swift-specific functionality (like modules and static or table-driven function dispatch) that you don't really want to break.

- You will want to make objects which derive from NSObject as small as possible and decompose the ones you do make into pieces which isolate UIKit functionality into an adaptor back into Swift.

- When creating enums, the strong temptation is to treat them similarly to NS_ENUM and use raw types like Int and String. This is usually too inflexible as a design.

- Much more frequently than you think initially, you will want to use associated values in your enum.

- If you are familiar with C, you should practice thinking of enum as a C union type rather than a C enum type.

- Remember that tuples work very well as associated values for enums

- Understand the tight relationship between Protocols and their implementation via generic witnesses. This explains behavior that can frequently be surprising when using protocol extensions.

- Anywhere you think you need to create a delegate protocol, you almost certainly need to just use closures or maybe a protocol witness struct instead.

- Protocols in swift are much more thoroughly part of the type system than they are in ObjC. You should understand how they work with generics and protocol witnesses.

- You should understand the deeper implications of Protocol's use of associatedtype. There are a ton of error messages you will never understand if you don't.

- You should always ask yourself if there may be more than one way for a type to conform to a protocol. If you can envision it at all, i.e. if the creation of the type is not simply to provide a specific concrete implementation of the protocol, then you should consider using a protocol witness rather than adding a conformance.

-

Familiarize yourself with the use of ALL of the following functions on sequence:

- map

- zip

- flatMap

- compactMap

- lazy

- reduce

- first/first(where:)

- contains(where:)

- drop(while:), dropFirst(), dropLast()

- enumerated

- sorted(by:)

- joined()

- filter(where:)

- shuffled

- prefix/prefix(while)

- suffix

- allSatisfy(where:)

- publisher

- forEach

-

forEachis listed last, because its use should be only as a last resort as it returns Void. As mentioned above, void returning functions should be avoided, so its use should be limited to interfacing into legacy imperative code. -

The most common case where

forEachcan't be avoided is walking over collections of UIKit objects to change their state. -

The one other place you might make an exception is where you have a mutating method on a struct for performance reasons.

-

The rest of the elements of the list above0] are all frequently used and provide very good practice for using Combine.

-

Properly used, the above methods obviate the need to ever use for-loop's. (Really, they do, you don't need the

forstatement, ever). -

map/zip/flatMap are listed first and in that order for a reason, these three have huge applicability in almost every generic you will ever write. You should begin to understand the theory here by practicing on Sequences.

-

If you find yourself doing a sequence of maps, compose the mapping functions together and use a single map instead

-

Understand how Combine and Sequence are alike and how they are different.

-

This is critical - you should NEVER construct an array using the reduce method. Doing so is O(n^2) when there are O(n) options available.

-

Any place that you are building up a Collection with a series of append statements, you should look to do that with a static Collection. Due to the fact that Collections in swift are value types, doing it with append (unless you are very careful) ends up requiring quadratic time.

- Look at everywhere you currently use for-loop constructs and try to visualize it as a chain of map, reduce, filter, zip, flatMap, compactMap, first(where:), contains(where:), shuffled etc.

- Any place that you declare an Array or Dictionary as a var and then immediately follow the declaration with a for-loop that fills the var, you should be using the higher order functions. The key is to think of the higher order functions on Sequence as specializations of a for-loop.

- Prefer guard / guard-let to if / if-let wherever possible. If you find that you have an if block that covers most of your function, you really want to use a guard construct.

- Understand the generic parts of the type system. All of the higher order functions are about working on generic types. When that really sinks in, you'll wonder how you ever got along without real, reified generics.

- Specifically, understand how and why Optional, Result and various Combine Publisher types are generic enums and structs.

- Take a look at Swift 5.1's property wrappers to gain a better understanding of generics. They will change your life.

- Learn about KeyPaths. Again, they will change your life and help you write better generic code

- Many ObjC programmers think that the higher order functions apply only to Array (or if they think about it, Sequence).

- This is largely because the only generic type other than Array that they are familiar with is Optional.

- With Optional they already have, in the nil keyword and the ? / ! syntax, a mental model that when coupled with Xcode's suggestions while writing optional-chaining code, will suffice for many uses.

- This causes them to lose sight of Optional as a generic enum and creates confusion when they are subsequently faced with map/zip/flatMap on other generics.

Accordingly, you should work to:

- Understand and be aware of the use of higher order functions on Optional and Result as well as on Sequence.

- Specifically study why map, zip and flatMap apply to Optional and Result and are not just methods on Sequence-conformant types like Array and Range.

- On Result, you need to also add an understanding of mapError, flatMapError (and how one would write a zipError) and why those functions exist.

-

Look at the source code for optional and understand that it is a generic enum and why that is

-

Avoid using optionals without a good reason - doing this removes the need to check for X == nil everywhere and erases a lot of code.

-

Avoid using the nil keyword in your code and use .none instead.

-

I've observed that the use of nil causes people with a background in ObjC to be confused about the Optional type. In ObjC nil == nil everywhere - it's just an alias for 0x0. Propagating nil in this sense from ObjC into Swift was an unfortunate though understandable decision in that it makes it seem as if nil is in some sense a special object where in fact it is almost always aliasing .none. In Swift, Optional

.none is not the same value as Optional.none is not the same value as Optional<optional>.none. </optional

-

Good practice is to get out of the habit of thinking of nil as a special value and instead use the actual value you mean: .none.

-

There are only two cases where nil should be used:

-

when returning from a failable initializer it is syntactically required

-

when referring to the .none case of Optional

-

-

In both cases it seems that the limitation is strictly a missing feature of the compiler and I would expect it to be removed in the future

-

Don't declare variables as Optional simply to avoid having to initialize them.

-

Corollary to this: don't create an object until you have all the values necessary to do so, then create it with the required values. Curried initializers are good for situations where you accumulate the initialization values gradually.

-

Sometimes (like in UIViews loaded from storyboards) it is not possible to avoid optionality due to Apple mandating initialization of an optional happening after allocation. This case is a particularly good use of implicit rather than explicit optionality.

-

When you do use optionals, try to remove the optionality as soon as possible, I.e. if you find yourself repeatedly using optional chaining on a variable, you should see about removing the optionality sooner. This is especially true of the use [weak self] and self?.

-

Related to the previous statement: best practice is to use a guard let self = self construct at the top of [weak self] closures.

-

Understand that optional chaining using ? is actually just syntactic sugar over Optional.flatMap. You should work on understanding why that is until it seems intuitive.

- Understand why result has two different types of map and flatMap (and zip, were we to implement it)

- Function chaining is an incredibly valuable technique. Anywhere in ObjC where you would return have a **NSError argument to indicate failure, you should instead use Result to chain subsequent calls in a manner similar to the use of Optional.

- Frequently you can also dispense with throwing in your APIs and return Result instead. Then you can let the Result propagate the error you would otherwise have to catch.

- You will still have to perform a do/try/catch at the end where you call get, but it vastly simplifies your API's to propagate errors this way.

- Calls which invoke callback closures should instead return a Swift 5 Result object and .success should never be nil. Even better, they should return a SwiftNIO EventLoopFuture. Conceivably success could return Void as its associated value but that should not be the standard behavior.

- It is difficult to overstate how important it will be to understand the Combine framework.

- Combine can best be understood as a Sequence without the makeIterator or next functions.

- I.e. Publisher is an implementation of the parts of the Sequence protocol where the individual elements of the sequence are delivered to the higher-order function asynchronously, one at a time rather than being pulled through the function using makeIterator and next.

- Seriously, that's all combine is.

- And that completely explains why the Publisher protocol looks so much like Sequence.

- Start studying the Combine library by starting with PassthruSubject. This is the standard way to adapt Combine to your imperative-style code, usually in the form of some network access or other asynchronous code.

- Once you understand what happens in a map/flatMap/mapError/flatMapError in that setting, replace your PassthruSubject/send() construct with a Defer/Future construct for example.

- Be aware that all of the asynchronous types in the Foundation library have had Combine Publishers added to them and many of the synchronous types (e.g. Array) as well.

- Look at SwiftNIO to really understand Promises and Futures.

- In particular look at EventLoopPromise and EventLoopFuture.

- Also take a look at Channel to understand how thread-safe code is written under SwiftNIO

- Even though the Concurrency Manifesto now seems out of date it is a really good resource for thinking about how Swift is likely to evolve towards a strongly functional Actor model.

- Swift is really good at interfacing with straight C.

- It's not so good at interfacing with C++

- Most of the places you will need to do this nowadays will be in handling of byte buffers.

- There are a number of withUnsafeXXX { } constructs which you should be familiar with if you are working with Data objects.

- MORE TO BE ADDED HERE

- As of early 2020, you should avoid the use of storyboards and UIKit where ever possible and use SwiftUI.

- Building new code on UIKit is knowingly adding tech debt which will need to be rewritten from scratch in the not too distant future if you do not start planning for a major architectural shift soon.

- In places where UIKit is still required you should examine how to drive your UI in an FRP style rather than in traditional MVC style.

- Examine all of your instance methods to make sure they actually make use of self. If a method doesn't use self, make it static.

- Remove unnecessary uses of the self keyword (which is pretty much all of them outside of a closure).

- Incidentally, really understanding why you have to specify the use of self in a closure, rather than just accepting it as a weird syntactic requirement that Xcode makes you add, is a marker that you have properly internalized Swift's functional programming core.

- Avoid declaring types of variables. Let type inference do its job, you almost never need to declare types on the left hand side of an initialization.

- If you need to read a type, let Xcode tell you its type.

- Sometimes, in long invocation chains, you will need to declare types to help the compiler figure out the types. This should be done only when the compiler barks at you about it and you should recognize what the barking means.

- Never use constructs like aBool == true or aBool == false, just use aBool or !aBool instead

- Simulated Higher Kinded Types (HKTs). While swift has syntax for generic types in protocols, it does not have syntax for generic functions in protocols. (Exercise try to write a protocol for a generic type F parameterized by T which implements the following signature:

map<U>(transform: (T) -> U) -> F<U>

It's not possible to write map because you can't add the generic type which parameterizes the return value. The Generics Manifesto was recently modified to address this and PATs will eventually get generic associated types at which point a pretty good facsimile of higher kinded types will be available in Swift.

-

Memory Semantics: Library writers will need to understand the memory semantics coming soon. If that is you, specifically you need to know when move, borrow, and copy apply as described in The Ownership Manifesto Basically this is what is needed to make Swift fast enough to be a systems programming language to replace C. The memory ownership model is almost completely stolen (errrrr... borrowed) from Rust and there's loads of resources out there on the Rust implementation. Since the model is "opt-in" on top of the conservative model Swift has always had under ARC, programmers will have to be aware of these things in order to maximize performance of their code.

-

ABI Stability -> Module Stability -> Binary compatibility: How Swift Achieved Dynamic Linking Where Rust Couldn't is absolutely the best explanation I have seen of why all this is important. People writing libraries need to be aware of every detail in it because they will eventually want to implement their own sort of stability. You should also be aware of: https://swift.org/blog/abi-stability-and-more/ this post as the best explanation of the future direction. And of course there's the official manifesto itself

-

Concurrency: Swift lacks a good concurrency model. This keeps it from being a complete system programming language and as this is a core goal of the language we can assume that this is being actively worked on by the core team. We can also assume that the new memory semantics will be the basis on which a new concurrency model is implemented. There's a lot to think about here. Here are some data points:

- the concurrency manifesto that Lattner and Groff were writing: The Concurrency Manifesto seems to have been abandoned. There have been no steps to implementing it taken in Swift 5 and no changes to the document in a long time. It specifies the addition of Async/Await and an Actor model in the language.

- there was also a concrete proposal for Async/Await by the same authors. It was even tentatively scheduled as a Swift Evolution proposal (i.e. the title of the doc is SE-XXXX). Again, no steps toward implementation in master seem to have been taken.

- Apple has been completely silent about open sourcing the Combine framework which has led to numerous open source projects trying to implement an identical solution for use on non-Apple platforms. The silence and failure to include such obviously important APIs in either the Std Lib or in the Unix distributions of Swift could be indicative of major changes coming in this area.

- The main themes for Swift 6.0 were recently published and those are: expanding Swift to other platforms and taking Concurrency forward. In short, stand-by for major improvements in the handling of asynchronous and concurrent APIs.

- SwiftNIO is all about concurrency and is built using industry standard techniques. It is very reasonable to presume that support for its techniques will work its way into actual language syntactic support.

-

The classic John Hughes paper on Why Functional Programming Matters:

-

The well-known Scott Wlaschin talk Functional Design Patterns also available as video

-

Pointfree's free episodes (personally I recommend you pay for a subscription if you are going to be a professional Swift programmer):

- Functions

- Side Effects

- Algebraic Data Types

- A Tale of Two Flat-Maps

- The Many Faces of Zip: Part 3

- SwiftUI and State Management: Part 1

- SwiftUI and State Management: Part 2

- SwiftUI and State Management: Part 3

- The Combine Framework and Effects: Part 1

- The Combine Framework and Effects: Part 2

- Swift UI Snapshot Testing

-

A whole series on Higher Kinded types

-

Various discussions on type theory in the Swift context

-

The Monad and HKT explanation that finally made sense of things for me.

-

Bow/Swift

- Bow is an attempt to introduce a complete set of Haskell-like HKT concepts into Swift. I wouldn't use it bc I think it needs support in the language to be used by mortals (which seems to be coming based on the Generics Manifesto), but the documentation is an incredibly helpful tutorial on why Swift needs HKTs and how you would use them if it had them natively.

- In particular, you will want to look at their documentation on emulating HKTs

-

Generic Associated Types

- Are now in the Generics Manifesto

- These can be used to create the Haskell-like signatures of HKTs

- Swift Method Dispatch

- Witnesses instead of protocols

- Trampolines as a means of coping with really deep recursion

- The new objc_msgSend

- OSSA improvements to the SIL

- Syntactic Sugar in Swift