My work on the 42Born2Code Philosophers project.

In this project, you will learn the basics of threading a process.

You will see how to create threads and you will discover mutexes.

Here are the things you need to know if you want to succeed this assignment:

- One or more philosophers sit at a round table. There is a large bowl of spaghetti in the middle of the table.

- The philosophers alternatively eat, think, or sleep. While they are eating, they are not thinking nor sleeping; while thinking, they are not eating nor sleeping; and, of course, while sleeping, they are not eating nor thinking.

- There are also forks on the table. There are as many forks as philosophers.

- Because serving and eating spaghetti with only one fork is very inconvenient, a philosopher takes their right and their left forks to eat, one in each hand.

- When a philosopher has finished eating, they put their forks back on the table and start sleeping. Once awake, they start thinking again. The simulation stops when a philosopher dies of starvation.

- Every philosopher needs to eat and should never starve.

- Philosophers don’t speak with each other.

- Philosophers don’t know if another philosopher is about to die.

- No need to say that philosophers should avoid dying!

(+ click to expand)

- Compile project using

cc - Global variables are forbidden

- Program should take the following arguments :

number_of_philosophers die_t eat_t sleep_t [number_of_times_each_philosopher_must_eat]number_of_philosophers: The number of philosophers and also the number of forks.die_t(in milliseconds): If a philosopher didn’t start eating die_t milliseconds since the beginning of their last meal or the beginning of the simulation, they die.eat_t(in milliseconds): The time it takes for a philosopher to eat. During that time, they will need to hold two forks.sleep_t(in milliseconds): The time a philosopher will spend sleeping.number_of_times_each_philosopher_must_eat(optional argument): If all philosophers have eaten at leastnumber_of_times_each_philosopher_must_eattimes, the simulation stops. If not specified, the simulation stops when a philosopher dies.

- Each philosopher has a number ranging from 1 to

number_of_philosophers. - Philosopher

number 1sits next to philosopher numbernumber_of_philosophers. Any other philosopher numberNsits between philosopher numberN - 1and philosopher numberN + 1.

General rules

-

The philosophers alternatively eat, think, or sleep.

- While they are eating, they are not thinking nor sleeping;

- While thinking, they are not eating nor sleeping;

- While sleeping, they are not eating nor thinking.

-

There are also forks on the table. There are as many forks as philosophers.

-

Because serving and eating spaghetti with only one fork is very inconvenient, a philosopher takes their right and their left forks to eat, one in each hand.

-

When a philosopher has finished eating, they put their forks back on the table and start sleeping. Once awake, they start thinking again. The simulation stops when a philosopher dies of starvation.

-

Every philosopher needs to eat and should never starve.

-

Philosophers don’t speak with each other.

-

Philosophers don’t know if another philosopher is about to die.

-

No need to say that philosophers should avoid dying!

Rules for the mandatory part

- Each philosopher should be a thread.

- There is one for between each pair of philosophers. Therefore, if there are several philosophers, each philosopher has a fork on their left side and a fork on their right side. If there is only one philosopher, there should be only one fork on the table.

- To prevent philosophers from duplicating forks, you should protect the forks state with a mutex for each of them.

About the logs of the program

- Any state change of a philosopher must be formatted as follows:

- timestamp_in_ms X has taken a fork

- timestamp_in_ms X is eating

- timestamp_in_ms X is sleeping

- timestamp_in_ms X is thinking

- timestamp_in_ms X died

Replace timestamp_in_ms with the current timestamp in milliseconds and X with the philosopher number.

- A displayed state message should not be mixed up with another message.

- A message announcing a philosopher died should be displayed no more than 10 ms after the actual death of the philosopher.

- Again, philosophers should avoid dying!

The program must not have any data races.

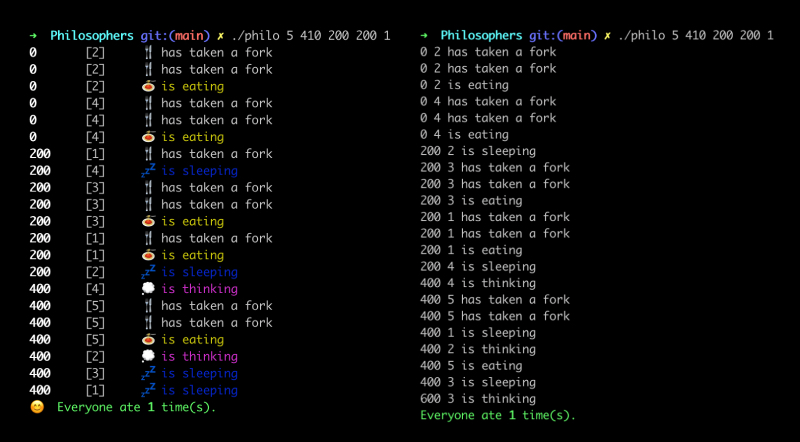

My program has a "visual mode" 🌈 that is used by default, but the basic output setting can be activated by compiling with flag

-D BORING.

graph TD;

A([Eat])-->B([Think]);

B-->C([Sleep]);

C-->A;

- Check and parse arguments.

- Avoid doing any

malloc()before checking every argument.- This way if anything is wrong you don't have to handle leaks.

- Avoid doing any

- Assign main t_rules variables with corresponding arguments.

- Initialize mutex.

- Link every philo to their correct

right_forkandleft_fork. - Correctly link the t_philo & t_rules structures (every t_philo node is indexed in t_rules, and all t_philos contain a link to rules)

- Create an

opti_sleep()function that allows tousleep()only by short increments and therefore not sleep if another philo has died while one was sleeping.- This keeps the simulation from hanging after a philo has died in this kind of test:

5 150 100 30000

- This keeps the simulation from hanging after a philo has died in this kind of test:

- Create a

print_status()function that is protected by a mutex, so different threads that will use it will not be able to use it simultaneously, printing gibberish.- It will also stop printing if someone is dead.

- Start

routine():- Philos pick up their forks.

- Odd philos pick up left

forkthen rightfork. - Even philos do the opposite.

- If there is only one philo in the simulation, it seems logical that they would pick up one

forkand, not being able to pick up a second one, would die atdie_t.- This is handled in the

fork_pickup()androutine()functions.

- This is handled in the

- Odd philos pick up left

- The once they have both their

forks, they starteating(), they put down their forks, then startsleepingandthinking.- This is where I check for dead philos, in the

change_state()function, which is called everytime a philo has to change its state.- I will print the new state (

x is eating), but before I sleep I check if the philo has enough time left to sleep the required amount by doing a simpleif (time_since_last_meal + time_to_sleep > philo->rules->die_t).- If the philo is too close to death and would not be able to sleep the full amount, it is marked as dead in the main structure and will only sleep until

philo->rules->die_t - time_since_last_meal.

- If the philo is too close to death and would not be able to sleep the full amount, it is marked as dead in the main structure and will only sleep until

- I will print the new state (

- This is where I check for dead philos, in the

- If a philo is marked as dead:

- The

print_status()function will stop printing anything, unlesssomeone_died >= 1and the message has the worddiedin it. - Then all the threads will finish their current routine and won't start it again since they can tell someone died.

- The

- If nobody dies, the routine stops by itself by checking if the current philo has eaten

number_of_times_each_philosopher_must_eat.

- Philos pick up their forks.

- In the main, all threads are

joinedso the program waits for them to finish. - At the very end I check if the number of philos that have eaten

number_of_times_each_philosopher_must_eatis equal to the number of philosophers in the simulation.- If so, a special message is printed on screen.

⚠️ How I handled if apthread_createorpthread_joinfailed (nobody checked for this case during evaluation but it was fun to think of a way to handle it) : I will print an error message on screen and setsomeone_died == -1, but I will not stop the program.- This way, the error message is printed, notifying that an

init/createfailed, but nothing else will print, and the simulation stops quickly sincesomeone_diedis no longer0. - Why do this ?

Because if I return from my program as soon as one of these fail, I will have leaks since I might exit the program while some threads are still running. - To do this, in my

main()(forpthread_join) andlaunch_philos()(forpthread_create), if there is a failure I only store an error code in a local variable (initialized at0), and let thejoin/createloops run their normal courses. That error code (0or1) is captured in the main and returned.

- This way, the error message is printed, notifying that an

(tested for leaks and data races)

🟩 1 800 200 200 should die

🟩 5 800 200 200 should go on forever (mine lasts for > 1 minute)

🟩 5 800 200 200 7 simulation should stop after eating 7 times

🟩 4 410 200 200 should go on forever (mine lasts for > 1 minute)

🟩 4 310 200 100 should die (dies in ok time)

(The higher philo numbers work better in the BORING mode, compiling with -D BORING)

🟩 5 150 100 30000 philo should die and simulation should stop before sleep time is over.

🟩 199 620 200 200 50

🟩 199 610 200 200 50

🟩 199 600 200 200 50

🟩 200 450 200 200 50

🟩 200 440 200 200 50

🟩 200 420 200 200 50

🟩 200 410 200 200 50

- Number of philos is <= 0

- Number of milliseconds is <=0 (= 0 aussi ?)

- Arguments contain forbidden characters

- Argument overflow ( >

MAX_INT) - Argument underflow (<

MIN_INT)

- Any of the parameters are incorrect

- Malloc failed

- For the forks

- For the philo struct array

- For any of the philo structs in the array

- Mutex_init failed

- Thread init failed

- ⭐ Philo dies

- ⭐ Odd number of philo dies

- ⭐ Single philo dies

- Philos are basically structures.

- The program needs to be compiled and linked with special flag:

-pthread(see man) - Toujours tester avec

valgrind --tool=helgrindpour voir les data race- Mais aussi tester avec juste

valgrindparce que avechelgrindles leaks n'apparaissent pas

- Mais aussi tester avec juste

- Ne jamais tester le fonctionnement du programme avec

valgrindpar contre, parce que ça ralentit l'execution du programme. Il sert juste à checker les leaks. - Hint: try launching philos by even/odd number

- Keep in mind the first and last philo that are usually trouble.

- Think about how to check if a philo has died.

(+ click to open)

-

Difference between a process and a thread

- A thread is a subset of the process.

- It is termed a lightweight process since it is similar to a real process but executes withing the context of a process and shares the same resources allotted to the process by the kernel.

- All the threads running within a process share the same address space, file descriptors, and other process related attributes, but have their own registers and stacks.

- A stack register is a computer central processor register whose purpose is to keep track of a call stack (usually shortened to the stack).

-

- They occur when two or more threads can access shared data and they try to change it at the same time. Because the thread scheduling algorithm can swap between threads at any time, we don't know the order in which the threads will attempt to access the shared data. Therefore, the result of the change in data is dependent on the thread scheduling algorithm (i.e. both threads are "racing" to access/change the data).

- Problems often occur when one thread does a "check then act" (

checkif the value isX, thenactto do something that depends on the value beingX) and another thread does something to the value in between thecheckand theact. - Race conditions can be avoided by employing some sort of locking mechanism before the code that accesses the shared resource:

- for ( int i = 0; i < 10000000; i++ ) { //lock x x = x + 1; //unlock x }

- For more on locking, search for: mutex, semaphore, critical section, shared resource.

-

- The biggest issue wih using locks for synchronisation is deadlock. It basically happens when you have two bits of code, each of which holds one lock, but each one needs the other one's lock in order to proceed.

- If each bit of code needs only one lock at a time, deadlock will not occur, but unfortunately this is not always possible.

- The simplest way of avoiding deadlock when you need more than one lock is to enforce a locking order, in which you can acquire two locks only by doing so in a specified order.

- In this situation, if you acquire one lock and fail to acquire the other, then you must release the first lock and try again. The problem with this plan is that it may not be possible to release the first lock safely.

- Although this case is the simplest, it can become arbitrarily complex. One classic example is the "dining philosophers" problem. Each philosopher has a chopstick on either side of him and requires two to eat. They all start by picking up the chopstick on their right. Now they're deadlocked—no one can proceed until someone puts down his chopstick.

- You can also easily enter a livelock condition from here. If each philosopher puts down the chopstick on his right and tries to pick up the one on the left, then they're stuck that way. They may put the left one down and pick up the one on the right again, oscillating between two states without actually managing to eat.

- This problem could be avoided if each chopstick had a number, and they all had to be picked up in order. In this case, all of the philosophers would try to pick up the one on their right, except for the one sitting between the chopsticks with the highest number on one side and the lowest number on the other side. He would have to wait until the person using the chopstick on his left had finished before he could pick up the one on his right. Or he would get there first. In both cases, at least one person would be able to pick up both chopsticks. Once he'd finished eating, at least one more person would be able to start.

-

Mutex

- A mutex is a MUTual EXclusion device, and is useful for protecting shared data structures from concurrent modifications, and implementing critical sections and monitors.

- A mutex has two possible states:

unlocked(not owned by any thread), andlocked(owned by one thread). - A mutex can never be owned by two different threads simultaneously.

- A thread attempting to lock a mutex that is already locked by another thread is suspended until the owning thread unlocks the mutex first.

-

Researching the allowed external functions:

- memset

memset- fill memory with a constant bytevoid *memset(void *s, int c, size_t n);- The memset() function fills the first n bytes of the memory area pointed to by s with the constant byte c.

- usleep

int usleep(useconds_t usec);- The

usleep()function suspends execution of the calling thread for (at least) usec microseconds. The sleep may be lengthened slightly by any system activity or by the time spent processing the call or by the granularity of system timers.

- gettimeofday

#include <sys/time.h>int gettimeofday(struct timeval *restrict tv, struct timezone *restrict tz);- The

tvargument is astruct timeval(as specified in<sys/time.h>) and gives the number of seconds and microseconds since theEpoch(1970-01-01 00:00:00 +0000 (UTC)):

struct timeval { time_t tv_sec; /* seconds */ suseconds_t tv_usec; /* microseconds */ };

- The

tzargument is astruct timezone. The use of thetimezonestructure is obsolete; the tz argument should normally be specified asNULL.

struct timezone { int tz_minuteswest; /* minutes west of Greenwich */ int tz_dsttime; /* type of DST correction */ };

- To have the time in milliseconds, I have to do tv_sec * 1000 and tv_usec / 1000.

- pthread_create

int pthread_create(pthread_t * thread, pthread_attr_t * attr, void * (*start_routine)(void *), void * arg);- Creates a new thread and returns a thread identifier.

- Needs a pointer to a previously defined

pthread_tvariable. - If we don't want to set

pthread_attr_twe can set that toNULLand a default configuration will be set. - If the

start_routinefunction does not need arguments, thevoid * argargument can also be set toNULL.

- pthread_detach

int pthread_detach(pthread_t th);- The

pthread_detach()function marks the thread identified by thread as detached. When a detached thread terminates, its resources are automatically released back to the system without the need for another thread to join with the terminated thread. - Once a thread has been detached, it can't be joined with

pthread_join()or be made joinable again. - The detached attribute merely determines the behavior of the system when the thread terminates; it does not prevent the thread from being terminated if the process terminates using

exit()(or equivalently, if the main thread returns). - 🚨 Either

pthread_join()orpthread_detach()should be called for each thread that an application creates, so that system resources for the thread can be released. (But note that the resources of all threads are freed when the process terminates.)

- pthread_join

int pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **retval)- The

pthread_join()function waits for the thread specified by thread to terminate. (ndlr: This is basically thewaitpidfunction, but for threads.) - If

retvalis notNULL, thenpthread_join()copies the exit status of the target thread (i.e., the value that the target thread supplied to pthread_exit(3)) into the location pointed to by retval. - If the target thread was canceled, then PTHREAD_CANCELED is placed in the location pointed to by

retval.

- pthread_mutex_init

int pthread_mutex_init(pthread_mutex_t *mutex, const pthread_mutexattr_t *attr);- The

pthread_mutex_init()function initialises the mutex referenced bymutexwith attributes specified byattr.

- pthread_mutex_destroy

int pthread_mutex_destroy(pthread_mutex_t *mutex);- The

pthread_mutex_destroy()function destroys the mutex object referenced bymutex; the mutex object becomes, in effect, uninitialised. - A destroyed mutex object can be re-initialised using

pthread_mutex_init(); the results of otherwise referencing the object after it has been destroyed are undefined.

- pthread_mutex_lock

int pthread_mutex_lock(pthread_mutex_t *mutex));pthread_mutex_locklocks the given mutex.- If the mutex is currently unlocked, it becomes locked and owned by the calling thread, and pthread_mutex_lock returns immediately.

- If the mutex is already locked by another thread, pthread_mutex_lock suspends the calling thread until the mutex is unlocked.

- If the mutex is already locked by the calling thread, the behavior of pthread_mutex_lock depends on the kind of the mutex. (etc...) (see man for more)

- pthread_mutex_unlock

int pthread_mutex_unlock(pthread_mutex_t *mutex);pthread_mutex_unlockunlocks the given mutex. The mutex is assumed to be locked and owned by the calling thread on entrance to pthread_mutex_unlock.- If the mutex is of the ``fast'' kind (etc...) (see man for more)

- memset

- My visualizer

- ⭐ GDoc cbarbit

- ⭐ A great checker

- Philo visualizer

- 42 Project Tests

- Git barodrig

- Le dîner des philosophes

- Le problème des philosophes

- Plein de concepts intéressants

- Wednesday, May 25th

- Registered to the project.

- Thursday, May 26th

- General setup

- Parsing & error handling

- Friday, May 27th

- Finished setting up structures

- Allocated memory

- Setup leak cleaning

- Assigned left/right forks to each philosopher node

- Wednesday, June 22nd (it's been a slow month)

- Project finished and tested.

- Thursday, June 23rd

- Project pushed and validated ✅

Note: J'ai mis un peu de temps à finir ce projet, j'ai beaucoup aimé les notions mais le sujet comportait des zones d'ombre légèrement bloquantes (ex: "les philosophes ne doivent pas communiquer entre eux", veut tout et rien dire).