This repository contains a fast and readable approximation of the logarithmic and exponential functions. It should be easy to follow the C++ and Python code in the 'exp' and 'log' subdirectories.

I was always curious about the implementation of these functions and I finally found an excuse to learn how they work when I found that log was one of the hottest functions in a program that I was trying to optimize. I decided to write a fast approximation function and share my findings here.

Power is the multiplication of some base

>>> exp(2)

7.38905609893065

>>> log(exp(2))

2.0

>>> log(256)/log(2)

8.0

The libc implementation is accurate up to 1

ULP. In many cases this

accuracy is not useful because many programs don't need this level of accuracy.

We are going to implement faster implementations that are going to be less

accurate. Accuracy is not the only requirement. Some mathematical functions

need to be monotonic, because you want the ordering of

There are several tricks that we can use to approximate logarithmic and

exponential function: fitting a polynomial, reducing the range, using lookup

tables, and recursive reduced-precision helper functions and a few other. Let's

use these tools to approximate

The first step is to figure out how to approximate a region in the target function. To do that we'll use a polynomial.

We need to find coefficients that construct the polynomial that approximates

There are two tools that we could use. The first tool is a part of Scipy. Scipy has an SGD-based fitting technique, that can fit a polynomial in a few lines of python.

This is how we fit a polynomial with scipy:

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import curve_fit

from math import log

# Generate the training data:

x = np.arange(1, 2, 0.001)

y = np.log(np.arange(1, 2, 0.001))

# The polynomial to fit:

def func1(x, a, b, c, d): return a * x**3 + b*x**2 + c*x + d

params, _ = curve_fit(func1, x, y)

a, b, c, d = params[0], params[1], params[2], params[3]

The second solution is to use minimax polynomials with Sollya. Sollya is a floating-point development toolkit that library designers use. Minimax polynomials minimize maximum error and in theory should generate excellent results. This is a short Sollya script to find the polynomial coefficients:

display = decimal; Q = fpminimax(log(x), 4, [|D...|], [0.5, 1]); Q;

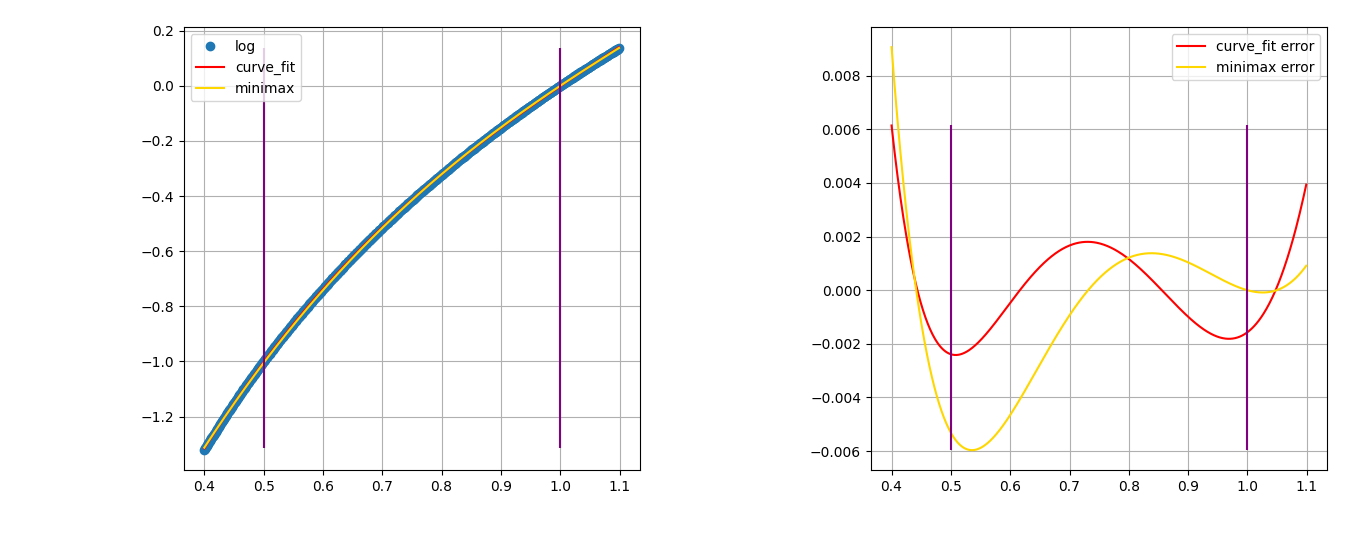

We've constructed a polynomial that approximates a function segment. Let's

evaluate how well it works. This is straight forward. Just subtract the real

function from the approximation function. As you can see the maximum error for

The polynomial approximation is accurate within a segment, but the error increases rapidly outside the target range. The next step is to figure out how to evaluate the entire range of the function. We use different tricks for each of the functions.

One of the identifies of the exponential function is

This makes things easier for us because we can evaluate the fraction using our polynomial, and we can evaluate the integral part using a small lookup table. The highest number that we can compute without overflowing double-precision floats is 710, so this is the size of our lookup table.

One way to handle negative numbers is to rely on the identity

And that's it. This is our implementation:

double expExp(double x) {

double integer = trunc(x);

// X is now the fractional part of the number.

x = x - integer;

// Use a 4-part polynomial to approximate exp(x);

double c[] = {0.28033708, 0.425302, 1.01273643, 1.00020947};

// Use Horner's method to evaluate the polynomial.

double val = c[3] + x * (c[2] + x * (c[1] + x * (c[0])));

return val * EXP_TABLE[(unsigned)integer + table_zero_idx];

}

Just like

This is an example of adjusting the range of the log input, in base-2.

>>> log(32, 2)

5.0

>>> log(16, 2) + 1

5.0

>>> log(8, 2) + 2

5.0

>>> log(4, 2) + 3

5.0

>>> log(2, 2) + 4

5.0

We could write this code:

// Bring down large values.

while (x > 2) {

x /= 2;

shift -= 1;

}

However, there is a better way. Again, we will split the input into integral and fraction components, but this time we are going to rely on the underlying representation of the floating point number, that already stores the number as a multiplication of a power-of-two. The exponent bits of the float/double are what we need to figure out the log bias.

The function

And that's it. This is the code:

double fastLog(double x) {

/// Extract the fraction, and the power-of-two exponent.

auto a = my_frexp(x);

x = a.first;

int pow2 = a.second;

// Use a 4-part polynom to approximate log2(x);

double c[] = {1.33755322, -4.42852392, 6.30371424, -3.21430967};

double log2 = 0.6931471805599453;

// Use Horner's method to evaluate the polynomial.

double val = c[3] + x * (c[2] + x * (c[1] + x * (c[0])));

// Compute log2(x), and convert the result to base-e.

return log2 * (pow2 + val);

}

Libc implementations usually use 5-term to 7-term

polynomials for calculating

The C++ implementation uses Horner's method for fast evaluation of small polynomials. Notice that we can rewrite our polynomial this way:

Horner's representation requires fewer multiplications, and each pair of addition and multiplication can be converted by the compiler to a fused multiply-add instruction (fma).

Make sure to compile the code with:

clang++ bench.cc -mavx2 -mfma -O3 -fno-builtin ; ./a.out

Benchmark results:

EXP:

name = nop, sum = , time = 163ms

name = fast_exp, sum = 1.10837e+11, time = 166ms

name = libm_exp, sum = 1.10829e+11, time = 383ms

LOG:

name = nop , sum = , time = 165ms

name = fast_log, sum = 1.46016e+08, time = 167ms

name = libm_log, sum = 1.46044e+08, time = 418ms