Today you will implement your very own HashMap. If this sounds tricky, don't worry--we've provided specs.

- Be able to write a resizing array class

- Be able to describe the characteristics of a good hashing function

- Be able to explain how a linked list works and know how to traverse it

- Be able to explain how a hash map works

- Know how to implement an LRU cache using hash maps and linked lists

A Set is a data type that can store unordered, unique items. Sets don't make any promises regarding insertion order, and they won't store duplicates. In exchange for those constraints, sets have remarkably fast retrieval time and can quickly look up the presence of values.

Many mathematicians claim that sets are the foundation of mathematics, so basically we're going to build all of mathematics today. No big deal.

A set is an abstract data type (ADT). An ADT can be thought of as a high-level description of a structure and an API (i.e., a specific set of methods). Examples of ADTs are things like sets, maps, or queues. But any given data type or API can be realized through many different implementations. Those implementations are known as data structures.

Different data structures can implement the same abstract data type, but some data structures are worse than others. We're going to show you the best implementations, or close to them. (In reality, there's usually no single best implementation of an ADT; there are always tradeoffs.)

Sound cool yet? Now let's go build a Set.

We'll start with the first stage. In this version of a set, we can only store integers that live in a predefined range. So I tell you the maximum integer I'll ever want to store, and you give me a set that can store it and any smaller positive number.

- Initialize your MaxIntSet with an integer called

maxto define the range of integers that we're keeping track of. - Internal structure:

- An array called

@store, of lengthmax - Each index in the

@storewill correspond to an item, and the value at that index will correspond to its presence (eithertrueorfalse) - e.g., the set

{ 0, 2, 3 }will be stored as:[true, false, true, true] - The size of the array will remain constant!

- The

MaxIntSetshould raise an error if someone tries to insert, remove, or check inclusion of a number that is out of bounds.

- An array called

- Methods:

#insert#remove#include?

Once you've built this and it works, we'll move on to the next iteration.

Now let's see if we can keep track of an arbitrary range of integers.

Here's where it gets interesting. Create a brand new class for this one.

We'll still initialize an array of a fixed length--say, 20. But now,

instead of each element being true or false, they'll each be

sub-arrays.

Imagine the set as consisting of 20 buckets (the sub-arrays). When we

insert an integer into this set, we'll pick one of the 20 buckets where

that integer will live. That can be done easily with the modulo

operator: i = n % 20.

Using this mapping, which wraps around once every 20 integers, every integer will be deterministically assigned to a bucket. Using this concept, create your new and improved set.

- Initialize an array of size 20, with each containing item being an empty array.

- To look up a number in the set, modulo (%) the number by the set's length, and add it to the array at that index. If the integer is present in that bucket, that's how we know it's included in the set.

- You should fill out the

#[]method to easily look up a bucket in the store - callingself[num]will be more DRY than@store[num % num_buckets]at every step of the way! - Your new set should be able to keep track of an arbitrary range of integers, including negative integers. Test it out.

The IntSet is okay for small sample sizes. But if the number of elements grows pretty big, our set's retrieval time depends more and more on an array scan, which is what we're trying to get away from. It's slow.

Scanning for an item in an array (when you don't know the index) takes

O(n) time, because you potentially have to look at every item. So if we're

having to do an array scan on one of the 20 buckets, that bucket will have on

average 1/20th of the overall items. That gives us an overall time

complexity proportional to 0.05n. When you strip out the 0.05 constant

factor, that's still O(n). Meh.

Let's see if we can do better.

- Make a new class. This time, let's increase the number of buckets as

the size of the set increases. The goal is to have

buckets.length > Nat all times. - You may want to implement an

inspectmethod to make debugging easier. - What are the time complexities of the operations of your set implementation?

A hash function is a sequence of mathematical operations that deterministically maps any arbitrary data into a pre-defined range of values. Anything that does that is a hash function. However, a good hash function satisfies the property of being uniform in how it distributes that data over its range of values.

To create a good hash function, we want to be able to hash absolutely anything. That includes integers, strings, arrays, and even other hashes.

Also, a hash function should be deterministic, meaning that it should always produce the same value given the same input. It's also essential that equivalent objects produce the same hash. So if we have two arrays, each equal to [1, 2, 3], we want them both to hash to the same value.

So let's construct a nice hashing function that'll do that for us. Be creative here!

Write hash functions for Array, String, and Hash. Build these up sequentially.

- Use

Fixnum#hashas a base hashing function. The trick here will be to create a scheme to convert instances of each class to aFixnumand then apply this hashing function. This can be used onNumerics such as the index of an array element.- Don't try to overwrite Ruby's native

Fixnum#hash; making a hash function for numbers is something that's outside the scope of this assignment.

- Don't try to overwrite Ruby's native

- Ordering of elements is essential to hashing an

ArrayorString. This means each element in anArrayorStringshould be associated with its index during hashing. Ex.[1, 2, 3].hash == [3, 2, 1].hash # => false - On the other hand, ordering is not to be considered with a

Hash. Hashes are based on sets and have no fixed order. Ex.{a: 1, b: 2}.hash == {b: 2, a: 1}.hash # => true

- Can you write

String#hashin terms ofArray#hash? - When you get to hashing hashes: one trick to make a hash function order-agnostic is to turn the object into an array, stably sort the array, and then hash the array. This'll make it so every unordered version of that same object will hash to the same value.

- Don't spend more than 30 minutes working on hashing functions. Great hashing functions are hard to write. Your goal is to write a good-enough hashing function and move forth to the fun stuff ahead! Call over a TA if needed.

- Avoid using byebug inside your hash methods. The functioning of byebug's internal code will cause this to break since it calls Array#hash.

- You may want to refer to the resource on

XOR (

^in Ruby). XOR is a great tool for hashing because it's fast, and it provides a good, nearly uniform output of bits.

More reading on hash functions.

Now that we've got our hashing functions, we can store more than just integers. Let's make it so we can store any data type in our set.

This will be a simple improvement on ResizingIntSet. Just hash every

item before performing any operation on it. This will return an integer,

which you can modulo by the number of buckets. Implement the #[] method to dry up your code. With this simple

construction, your set will be able to handle keys of any data type.

Easy as pie. We now have a fabulous set that works with any data type!

Now let's take it one step further.

Up until now, our hash set has only been able to insert and then check for inclusion. We couldn't create a map of values, as in key-value pairs. Let's change that and create a hash map. But first, we'll have to build a subordinate, underlying data structure.

A linked list is a data structure that consists of a

series of nodes. Each node holds a value and a pointer to the next node (or nil). Given a pointer to the first (or head) node, you can access

any arbitrary node by traversing the nodes in order.

We will be implementing a special type of linked list called a "doubly linked list" - this means that each node should also hold a pointer to the previous node. Given a pointer to the last (or tail) node, we can traverse the list in reverse order.

Our LinkedLists will ultimately be used in lieu of arrays for our HashMap buckets. In order to make the HashMap work, each node in your linked list will need to store both a key and a value.

The Node class is provided for you. It's up to you to implement the

LinkedList.

There are a few ways to implement LinkedList. You can either start with head and tail of your list as nil, or start them off as sentinel nodes. We recommend using sentinel nodes because they can help you avoid unnecessary type checking for nil.

A sentinel node is merely a "dummy" node that does not hold a value. Your LinkedList should keep track of pointers (read: instance variables) to sentinel nodes for its head and tail. The head and tail should never be reassigned.

Given these properties of our LinkedList, how might we check if our list is empty? How might we check if we are at the end of our list? Think about how your linked list will function as you implement the methods below.

Go forth and implement the following methods:

firstempty?#append(key, val)- Append a new node to the end of the list.#update(key, val)- Find an existing node by key and update its value.#get(key)#include?(key)#remove(key)

Specs await!

Once you're done with those, we're going to also make your linked lists

enumerable. We want them to be just as flexible as arrays. Remember back

to when you wrote Array#my_each, and let's get this thing enumerating. The block passed to #each will yield to a node.

Once you have #each defined, you can include the Enumerable module

into your class. As long as you have each defined, the Enumerable

module gives you map, each_with_index, select, any? and all of

the other enumeration methods for free! (Note: you may wish to refactor your #update, #get, and #include methods to use your #each method for cleaner code!)

So now let's incorporate our linked list into our hash buckets. Instead

of Arrays, we'll use LinkedLists for our buckets. Each linked list will

start out empty. But whenever we want to insert an item into that

bucket, we'll just append it to the end of that linked list.

So here again is a summary of how you use our hash map:

- Hash the key, mod by the number of buckets (implement the

#bucketmethod first for cleaner code - it should return the correct bucket for a hashed key) - To set, insert a new node with the key and value into the correct bucket. (You can use your

LinkedList#appendmethod.) If the key already exists, you will need to update the existing node. - To get, check whether the linked list contains the key you're looking up

- To delete, remove the node corresponding to that key from the linked list

Finally, let's make your hash map properly enumerable. You know the

drill. Implement #each, and then include the Enumerable module.

Your method should yield [key, value] pairs.

Also make sure your hash map resizes when the count exceeds the number of buckets! In order to resize properly, you have to double the size of the container for your buckets. Having done so, enumerate over each of your linked lists and re-insert their contents into your newly-resized hash map. If you don't re-hash them, your hash map will be completely broken. Can you see why?

Now pass those specs.

Once you're done, you should have a fully functioning hash map that can use numbers, strings, arrays, or hashes as keys.

Let's upgrade your hash map to make an LRU Cache.

LRU stands for Least Recently Used. It's basically a cache of the n

most-recently-used items. In other words, if something doesn't get

looked at often enough, we trash it. It could be web pages, objects in

memory on a video game, or kitty toys. But it's usually not kitty toys.

If you're confused, that's okay. Just follow these basic principles, and you'll be fine.

- Your cache will only hold

maxmany items (you should be able to set themaxupon initialize). - When you retrieve or insert an item, you should mark that item as now being the most recently used item in your cache.

- When you insert an item, if the cache exceeds size

max, delete the least recently used item. This keeps the cache size always atmaxor below.

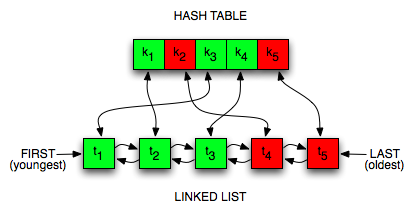

So that's our caching strategy. But how do we actually build this thing? Well, an LRU cache is built using a combination of two data structures: a hash map, and a linked list.

This is how we'll use the linked list: Each node in the list will hold a cached object. We'll always add new nodes to the end of the list, so the nodes at the end will always be the freshest, while those at the beginning are the oldest. Whenever an object is requested and found in the cache, it becomes the freshest item, so we'll need to move it to the end of the list to maintain that order.

Once the cache is full, we'll need to expire old entries too, so we'll remove items from the beginning since those are the oldest.

So just with that we've got a decent strategy for our LRU cache. Using a linked list, it's easy to add stuff, delete stuff, and to update its position among the most recently used items in our cache.

The only problem is lookup time. Linked lists are slow. If we want to

figure out if an item is in the cache, we have to look at each node

one-by-one; that's an O(n) traversal. That's not great. Let's see if

we can augment this with a hash map to make it faster.

Here's the plan: we'll create a hash map whose keys will be the same keys

that we put in our linked list. But unlike the linked list, our hash map won't

store the values associated with those keys. Instead, the hash map will

point to the node object in our linked list (if it exists). Every time

we update the LRU cache by inserting or deleting an element, we'll

insert it into our hash or delete it from our hash (which both take

O(1) time).

We'll have two data structures to keep in sync now, which is a little

more complicated. But the upside is that our hash map will allow us to

jump into the middle of the linked list instantly, in O(1) time.

That's awesome.

With this combination of data structures, we'll have O(1) lookup,

insertion, and deletion for our cache. You can't ask for better.

So let's map the same data in both a hash map and in a linked list.

- Let's say we're building an LRU cache that's going to cache the values

of the perfect squares. So our LRU cache will store a

@prc, which in this case will beProc.new { |x| x ** 2 }. If we don't have the value of any number's square, we'll use this Proc to actually compute it. But we don't want to compute it for the same number twice, so after I compute anything, I'll store it in my LRU cache. But if my LRU Cache gets an input that doesn't exist in the cache, it'll compute it using the Proc. - Now build your LRU cache. Every time you add a new key-value pair to

your cache, you'll take two steps.

- First, look to see if the key points to any node in your hash map. If it does, that means that the item exists in your cache. Before you return the value from the node though, move the node to the very end of the list (since it's now the most recently used item).

- Say the key isn't in your hash map. That means it's not in your

cache, so you need to compute its value and then add it. That has

two parts.

- First, you call the proc using your key as input; the output

will be your key's value. Append that key-value pair to the

linked list (since, again, it's now the most recently used

item). Then, add the key to your hash, along with a pointer to

the new node. Finally, you have to check if the cache has

exceeded its

maxsize. If so, call theeject!function, which should delete the least recently used item so your LRU cache is back tomaxsize. - Hint: to delete that item, you have to delete the first item

in your linked list, and

delete that key from your hash. Implemented correctly, these

should both happen in

O(1)time.

- First, you call the proc using your key as input; the output

will be your key's value. Append that key-value pair to the

linked list (since, again, it's now the most recently used

item). Then, add the key to your hash, along with a pointer to

the new node. Finally, you have to check if the cache has

exceeded its

And you did it! Congratulations!

Let's now do a problem that's more similar to what you'll be seeing in interviews. It might be one that you've already seen before, but the main idea is to try and use one of the data structures that you just built up!

Write a method to test whether the letters forming a string can be permuted to form a palindrome. For example, "edified" can be permute to form "deified".

You've probably realized that we should use a hash map here. Use the hash map class that you implemented! This time, when you're setting and getting, picture in your mind what's goin on under the hood within the hashmap.

For example, whenever you set a key-value pair, picture all the specific processes that's happening to the inputs.