- 1. Purpose

- 2. Repoistory Overview

- 3. Design

- 4. How to use

- 5. Results

- 6. Issues Encountered

- 7.Recommendations

Delft University of Technology is currently developing the Delfi-PQ, a 3U PocketCube spacecraft, expected to launch in 2019. Throughout its mission, Delfi-PQ will be in a severe radiation environment in low Earth orbit, which could potentially harm the spacecraft electronics. The radiation effect focused on in the present work is the Single Event Upset (SEU), which origins from ionizing particles interacting with the spacecraft electronics. The SEU is a soft error (recoverable) with unpredictable consequences. One of the consequences of SEUs are changes in memory locations, which could result in retrieving incorrect housekeeping data from the spacecraft.

Clearly SEUs should be corrected for, which is normally done by an on-board Fault Detection, Isolation and Recovery (FDIR) algorithm. FDIR algorithms are vital for the correct in-orbit operation of the Delfi-PQ and hence shall be tested extensively on Earth to validate correct function. For large spacecraft, this is often done by using radiation hardened electronics or by testing the flight computer in a radiation environment. Both these options add a lot of cost to the overall mission, which is often not possible for small spacecraft, such as Delfi-PQ. Therefore, the purpose of this repository is to simulate SEUs by means of real time fault injection, in an attempt to validate the Delfi-PQ FDIR algorithm.

The repository is made open-source and allows students from all over the world to contribute to the project.

In addition to the Readme, there are a few main files required to run the software. In the fault_injection folder there are two main files:

- client_ti.py the Python file to analyse the MSP432P401R LaunchPad.

- client_adb.py the Python file to analyse the FLATSAT ADB.

And in the PQ9EGSE folder there are two main files:

- target/PQ9EGSE-0.1-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar the java file which deploys the EGSE software.

- EPS.xml contain the definitions of all the requests that can be sent to the board.

Other files of note in the fault_injection folder are:

- error_graphs.py creates a graph of the error locations.

- pq_comms.py defines the requests as functions which can be executed with Python.

- testing.txt logs all the packets returned by the board.

Lastly, the folder figures contains all figures used in this documentation.

In the past, several attempts were already made on developing a FDIR validation simulation, which have been used throughout this work as a reference. Firstly, Delfi-PQ_FDIR, uses an Arduino to simulate the spacecraft. Errors are only injected in the SRAM memory and communication is done via standard USB serial. Error checking is done by asking housekeeping data, which contains the names of the authors as well as the Borwein pi approximation. Since both housekeeping parameters are fixed and can be well modelled, the authors can easily check for data corruption as a result of the faults injected. Their simulations outputs a memory map of the memory location and specific bits in which soft errors (corrupted housekeeping data) and hard errors (Arduino crash) occur.

Another attempt was made in the Delfi-PQ_FDIR_Evaluator, where the authors used two Texas Instruments MSP432P401R LaunchPad development boards, which is identical to the development board used in the present work. They use Python to inject error in the SRAM zone of the memory (0x20000000-0x20100000). Their board is programmed to continuously transmit the message "Hello World", which can have a different output if errors are introduced in the board. They distinguish four types of errors of which the two most relevant are: (1) lockup in which the boards stops responding and (2) data corruption in which the outputted "Hello World" string is corrupted.

In this work, the Electrical Ground Support Equipment (EGSE) for Delfi-PQ is used to inject faults in the memory. EGSE is stored in the folder PQ9EGSE which is cloned from this repository. Next to that the Python analysis and injection software files written in this work build upon the functions and structures obtained from this repository related to the integration testing of Delfi-PQ.

To simulate created errors due to SEUs the approach used in this work injects failures in the memory of the Delfi-PQ. The on-board memory is modelled with the FLATSAT interface or the MSP432P401R LaunchPad, which both have the same microcontroller. The memory map for the particular microcontroller used is shown in the figure below (source: Texas Instruments).

Like the previous iterations of the FDIR evaluation software, the errors are only injected in the SRAM region of the board, which is located at 0x20000000-0x20100000 (or at 0x01000000-0x01100000 on the code part, this is the same memory).

Testing of the FDIR of the different subsystems on-board of Delfi-PQ can be done in a modular way, by adding and removing different subsystems to the test environment, as shown in the figure below.

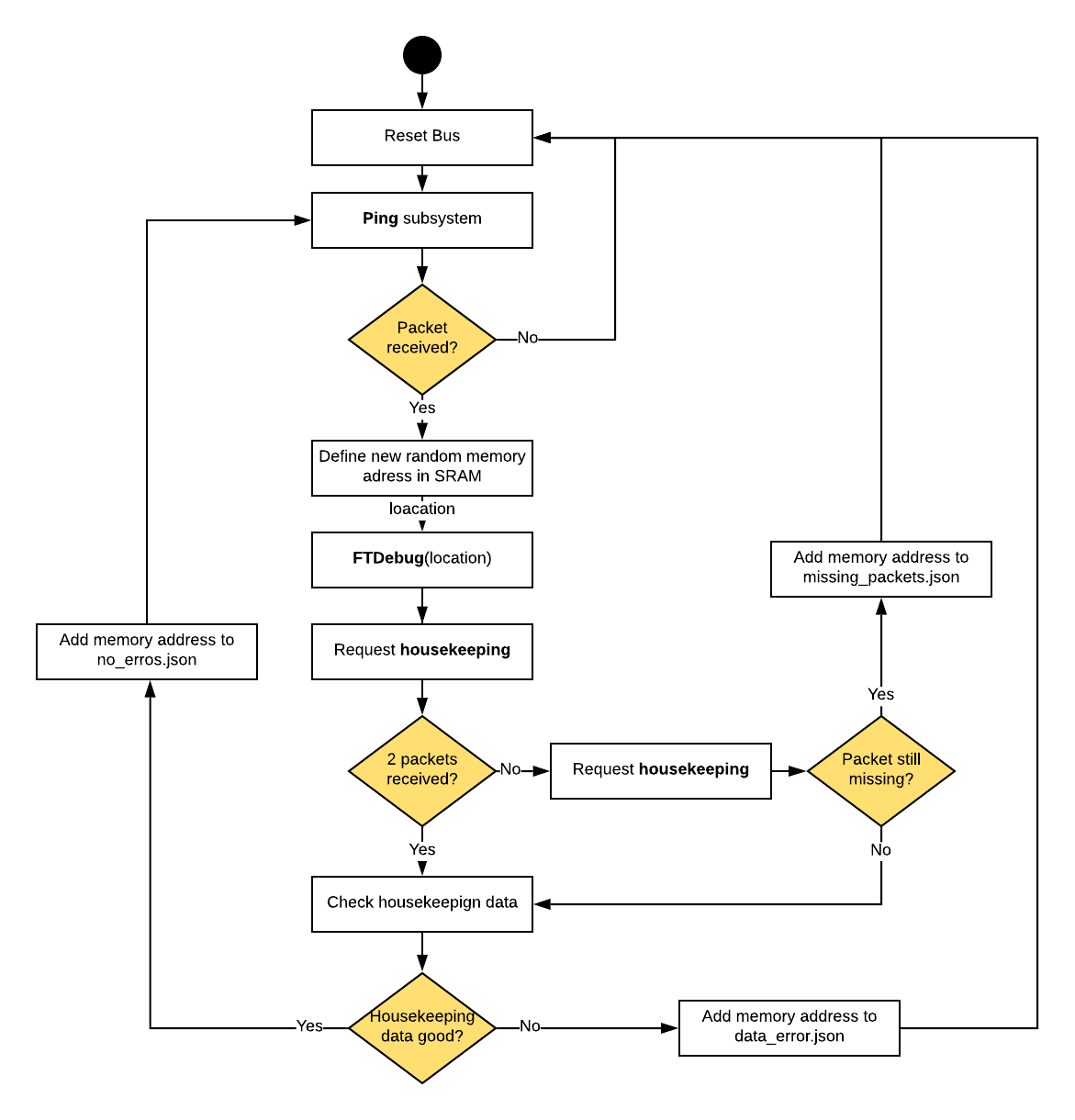

Here, the FLATSAT is used for communication between the spacecraft subsystems and computer for testing and debugging. FLATSAT can access the common bus for every subsystem and provides a small amount of processing of the data. Communication between FLATSAT and the subsystems is done via the RS-485 serial interface, and between FLATSAT and the computer via USB serial. On the computer one uses the EGSE application programing interface to transmit and receive data to the Delfi-PQ, via the FLATSAT. The errors can be injected in the SRAM manually via the EGSE GUI or automatically via the client_adb.py script written in Python. The software loop running on the client_adb.py file is shown in the flowchart below:

Every iteration of the loop starts with pinging the target subsystem, and checking if a packet is received back. If for some reason no packet is received, the bus is reset and a new ping command is sent to the the subsystem. Next, the memory address is defined in the SRAM memory range defined in the previous section, and Python's randint() function is used to generate addresses randomly within a given range. The range used is smaller than the full range of the SRAM as will be discussed later. In addition, a while loop is used to ensure no memory addresses are tested multiple times.

After the definition of the memory location to inject the fault in, the FTDebug function is called. Despite the target memory address, the function also requires a bit mask and an operator, which can either be set, clear or toggle. These operators essentially perform bitwise operations with the target byte and the mask byte, as shown in the figure below.

In the present work, the operator set is used, which is defined as and, and is paired with a constant bit mask of 255 (i.e. 0xFFFFFFFF). This command changes the target byte to the value 0xFFFFFFFF and hence injects a fault in the memory. Hereafter, a housekeeping request is sent to the target subsystem and the Python scripts verifies if two packets have been received (one from FTDebug and one from housekeeping). Packets can get lost during a lockup of the system as a result of the fault injection, or due to errors in the transmission, which are filtered out by the Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC) build in the PQ9 protocol. When the CRC finds an error in the communicated data, the EGSE application programming interface automatically rejects the packet. Hence, when running the client_adb.py, no packet will show up. To counteract this, a housekeeping loop is implemented, which which transmits a housekeeping request again when no packet is received. For more information about the CRC or PQ9 protocol, the reader is referred to the PQ9 and CS14 Interface Standard.

If two packets are received after sending the housekeeping request, the data error determination function is used, which is explained in more detail in section 3.4. If the data is error free the address is added to the no_error.json file, while if there is an error in the house keeping data the address is added to data_errors.json. However, if after re-requesting housekeeping, packets are still not returned the address is written to missing_packets.json, and the system is reset.

These .json files contain a list which is updated each time a new address is added. This ensures the data is stored if the Python code crashes or is restarted, and allows the data to be easily called to a Python script as a list for plotting as follows:

json_no_errors = r"address_logs/no_errors.json".replace('\\', '/')

no_errors = json.load(open(json_no_errors.replace('\\', '/')))

After errors are introduced in the system, it is of interest if these errors indeed propagate through the system or if the FDIR system successfully resolves the error. After introducing a SEU in the memory, we distinguish three different events:

- Housekeeping packet successfully received, without corrupted data.

- Housekeeping packet successfully received, but with corrupted data.

- No housekeeping packet received (lock up of system).

In case of a lock up of the system, no packets are transmitted by the FLATSAT or LaunchPad anymore. This system state can only be resolved by a power cycle (reset). However, detecting corrupted data is much harder, as this requires reference values to compare the data packets with. For this we first need to get a better understanding of the communication protocol used on the Delfi-PQ. The PQ9 protocol sends data in the form of packets, where the minimum packet length is 5 bytes and the maximum packet length is 255 bytes, based on the 8-bit architecture. The first byte contains the receiver to which the packet is sent, the second byte the size of the message transmitted, the third byte contains the transmitter and finally the last two bytes contain the CRC. A schematic overview of a packet for the housekeeping DEBUG service on the LaunchPad is shown below, where the message is highlighted:

The message contains the housekeeping information regarding the particular subsystem of Delfi-PQ. The length of this message is different for each subsystem, and parameters in the message are often variables (e.g. sensor readout), meaning modeling a reference signal on the computer to check for data corruption is near to impossible. For the DEBUG housekeeping command, some bytes have a constant value, which is shown in the figure in decimals.

The packets returned by invoking an ADB housekeeping request when connected to the FLATSAT are larger, but still contain variable bytes for the counter (which counts the number of packets transmitted by the subsystem) and fixed bytes representing testing 2 (0xcafe) and testing 4 (0xdeadbeef). The counter will be used to identify missing packages, while testing 2 and testing 4 will be used to check the data produced by housekeeping is not corrupted as a result of the SEU. While corrupt housekeeping data is not expected to be seen when running the code on the FLATSAT with the ADB, this method was used when it was initially connected to, to ensure the .xml file was operating nominally with it.

The LaunchPad board was used to test the FTDebug function was working properly, by testing the function at memory locations where the outcome was already know. At a memory address of "536874642", an operator set, and a bit mask of "255", it was known that the board would lock up, while at "536874742" a bit flip would cause no errors. These points were used to check both the EGSE and Python codes were running correctly.

Whenever the board locks up, or packets are missing, the flash memory must be reset before any more requests can be invoked. Resetting gets rid of the effects of the bit flip, and in the process resets the counter to 0. The reset has the same effects on both the Launchpad and the FLATSAT, but are invoked in different ways. In order to reset the TI Launchpad, the reset button on the side must be pressed. This is not ideal for testing a large amount of data points. However, for the FLATSAT the reset can be performed via software which switches the EPS bus off for 10 seconds, allowing the data to be collected without used input.

To transmit or receive data to or from the Delfi-PQ, the following items are required:

- Computer running on either Windows or LINUX, with Python 2.7 installed.

- Texas Instruments MSP432P401R LaunchPad.

- Micro USB to USB C cable.

- Delfi-PQ ADB subsystem with FLATSAT.

Download this repository and store it on your computer. Connect the FLATSAT or LaunchPad to the computer using the micro USB to USB C cable (LEDs should now blink on the board to verify it is powered). When using Windows, open Windows PowerShell in administrator mode and run the following command:

cd C:\...\FDIR_PQ9\PQ9EGSE

java -jar target/PQ9EGSE-0.1-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar

where the dots are to be replaced with the repository directory. When using LINUX, open the terminal and run the following command:

cd ...\FDIR_PQ9\PQ9EGSE

sudo java -jar target/PQ9EGSE-0.1-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar

Both cases will load the EGSE application programing interface. This can now be accessed by going to an internet browser and typing in the address bar:

localhost:8080

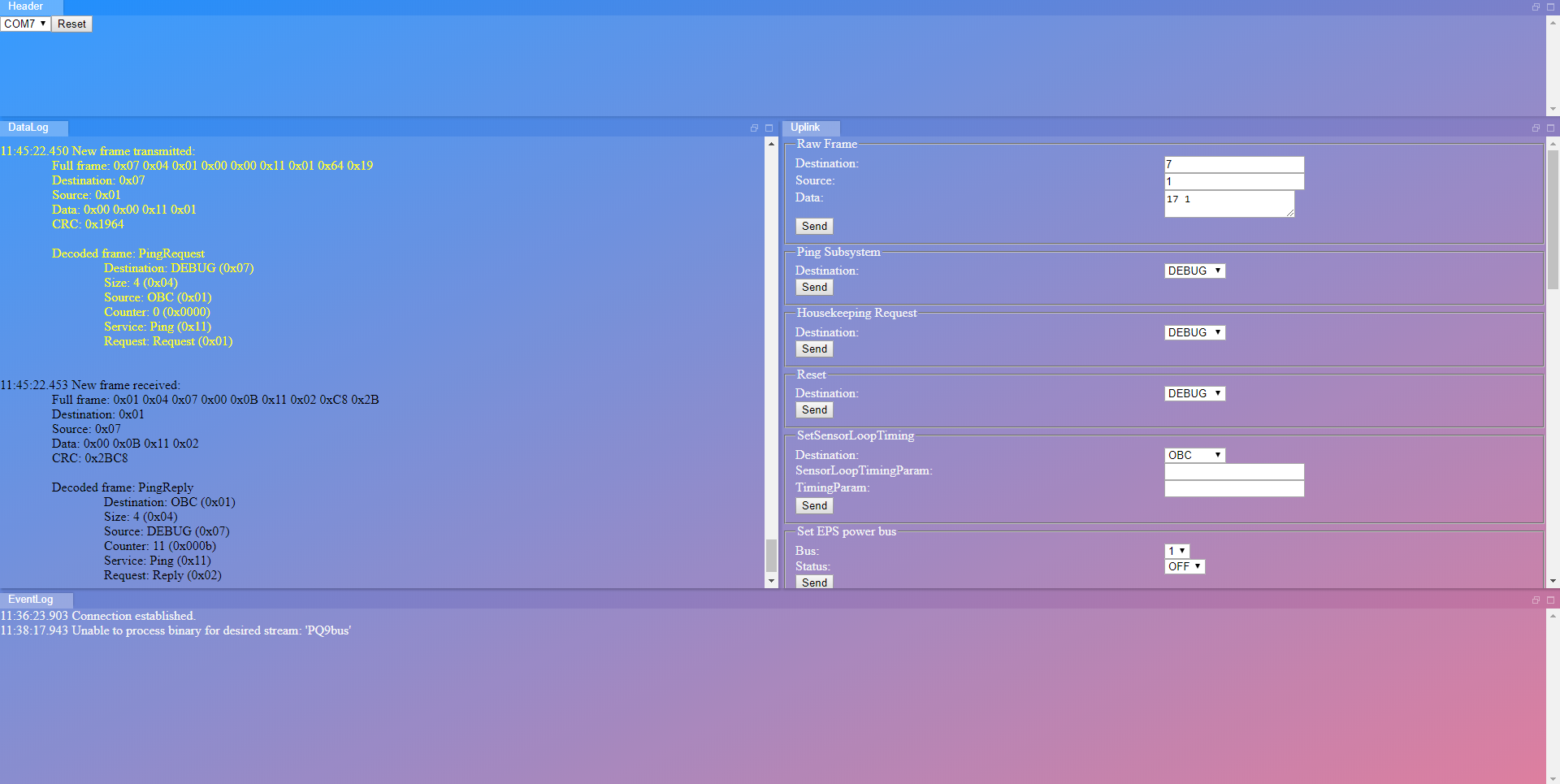

This will bring you to the EGSE GUI, as shown in the picture below. In the header, define the serial port used by the FLATSAT (COM7 in the figure). Note that one of the ports if for serial communication, and the other only for programming.

One can test if a successful connection is obtained by sending a ping request to DEBUG if connected to the LaunchPad or to ADB when connected to the Delfi-PQ hardware via FLATSAT. In the DataLog on the left side of the screen, a transmitted message should now prompt in yellow, as well as a received message in black. In case no message is received, or the command is not recognized by the EGSE software, the user is advised to shut down the EGSE application programming interface and re-deploy it with the steps described in this section.

Running the Python testing software is done via the client_adb.py when connected to the Delfi-PQ ADB subsystem via FLATSAT, or client_ti.py for testing the code with LaunchPad. One can open any Python 2.7 editor (e.g. IDLE) to open this file and run it. Additionally, one can also run the script directly via Windows Powershell or LINUX terminal when using the command:

cd ...\FDIR_PQ9\fault_injection

python client_adb.py

In both the EGSE GUI and the Python files, the memory address must be input in decimal, for which the range is 536,870,912 to 537,9191,488. At present client_adb.py looks in the range of 536,870,912 to 536,974,505, but this can be increased, by changing the randint() ranges on lines 133 and 136. Similarly, at present the code in client_adb.py has the destination for the requests set to "ADB" but this can be changed on line 93.

As was mentioned earlier, all the addresses tested are recorded in .json files, to ensure no data is lost should the Python crash. These are located in the folder address_logs. If Python has issues locating them, the path for their location can be updated at the beginning of the client_adb.py. The data stored in the .json files can be plotted with error_graphs.py as follows:

python error_graphs.py

This will provide the user with the plotting data as shown in section 5 of this documentation.

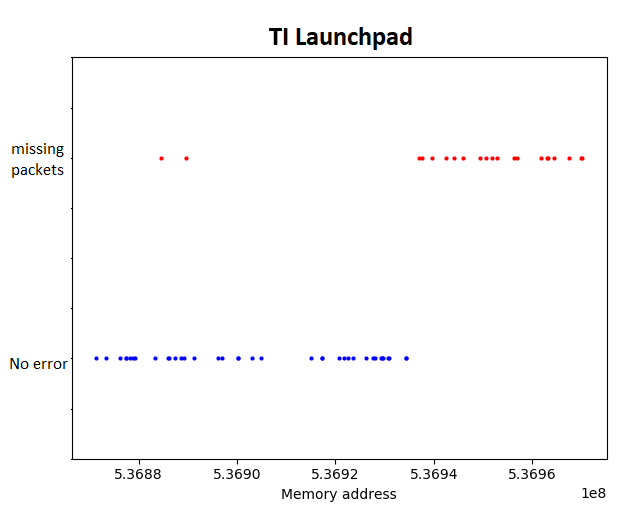

In the first phase of the software testing campaign tests were performed with the LaunchPad development board, where simple ping, housekeeping and FTDebug commands were tested. The LaunchPad board was configured to run on a software very comparable to the one present on FLATSAT, and provided a simple and fast way to verify the software. Testing the LaunchPad across the memory address range given above results in the following graph:

An attempt was made to compare the obtained data with previous tests with the LauchPad. However, it was quickly found out that the memory ranged used in the reference work (536,870,912 to 536,879,000) was much smaller and located near the lower bound of the full RAM memory range of 536,870,912 to 537,919,488 (i.e. 0x20000000 to 0x20100000) targeted in the present work. Similar to the previous work, most of the packets in this small region of comparison show no error. However, in the present work, actually no error is detected in these packages, whereas previous work does clearly show several lock ups of the system (missing packets). It is expected that these lock ups will also show up using our simulation, however it is likely no failures have been injected in these bits. Since the failure injection is a random, uniformly distributed process, and our memory range is much larger, the chance introducing an error in exactly the same bits as in the reference work is very small, and will only occur after the failure detection software has run for a sufficient time.

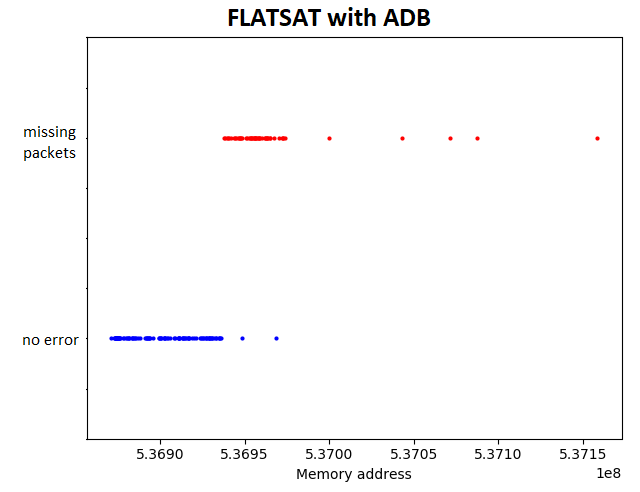

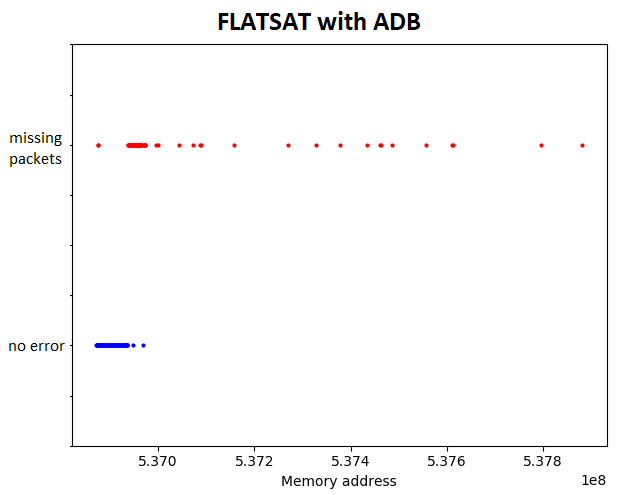

The second phase of the testing campaign consisted of tests with he FLATSAT with the ADB subsystem of Delfi-PQ attached. The client_abd.py was set up so that the destination of the requests was changed to "ADB" and the EPS power commands were sent to "Bus4Sw".

The FLATSAT was connected and run for approximately 30 minutes, which resulted in the error graph below. During this run, the memory address range described in section 4.2, and as expected, only one type of error was observed; that flipping a bit resulted in no packets being returned. Similar to what was seen with the LaunchPad, only a small portion of the SRAM memory range returned no errors when a bit was flipped. Similar to the LaunchPad, this range consisted of memory addresses mostly between 5.3687e8 and 5.3694e8.

To ensure this was main location where addresses resulted in no errors, the FLATSAT was briefly tested over the entire SRAM range of memory address, as is shown in the figure below. As was expected, in most of the SRAM bit flips resulted in missing packets.

Through out a project, a number of issues were encountered which slowed down progress substantially.

-

As was mentioned in section 3.5, when the TI LaunchPad freezes, and communication with it is no longer possible, the initial state can only be recovered by physically pressing the reset button on the board. This made testing a large range of data points time consuming for the user, who had to watch the script and reset the board as required. Fortunately the actual FLATSAT was reset-able with software.

-

The code was time consuming to run, it took 30 minutes to generate 175 data points. This was as a large number of time.sleep() were built into the programme. These served two purposes, to allow the board time to process and return the packets before the python script called them, and to allow the board to properly reset whilst it was turned off. The time.sleep() was set to 10 seconds for the reset, but could definitely be reduced in future versions.

-

Connecting the board to the EGSE software through the LINUX virtualbox environment took a few attempts each time. With either the environment not reconising the USB device, or the EGSE not responding to it and the whole environment having to be restarted.

-

The code initially received from the PQ_integretion_testing repo was not commented, so it took some time to figure out and build upon.

-

The naming convention in the EPS.xml file and the python files took some time to figure out, and in addition there were a number of spelling mistakes which had to be worked around for coding. For instance, the packet returned by the FTDebug command on the FLATSAT returned "Service":"Ackownledgment" as part of its dictionary. Little things like this took time to debug in the python code.

For future iterations of the fault injection software, the following items are recommended to implement.

- Allow for single SEU. Currently the FTDebug function only uses the set command with bit mask 255, which essentially sets the target byte to a value of 0xFFFFFFFF, no matter what the content of the byte is. It is recommended to also implement a function which allows for a single bit in the target byte to flip.

- Python 3 compatibility. Currently the Python fault injection software is only compatible with Python version 2.7. However, Python 3 is becoming the standard more and more, and hence making the functions compatible with this newer version would make the code more future-proof.

- Variable fault injection rate and target memory locations. Currently the FTDebug fault injection software randomly selects a single location in the memory to change in real time. However, in reality, multiple locations in the memory can be target by a single SEU strike. Therefore, the number of bytes in which faults are injected should also become a random process. This also ties together with making the fault injection rate a non-constant process. In the present work, every time step new faults are injected in the memory and packets retrieved. However, for real space missions, there can be points in time when no SEUs occur, or points in time where were different bytes in the memory are affected (e.g. when the spacecraft travels through the South Atlantic Anomaly). Therefore, the frequency and rate of fault injections should also be modelled with (random) variables for next iterations.

- Longer testing time. In this work, the longest fault injection test performed was in the order of 30 minutes. However, this is still much lower than the expected orbital period of Delfi-PQ. Therefore, it is recommended to perform longer tests, in the order of multiple orbital periods, to get a better idea of the correct functioning of the FDIR.

- Speed up testing time As was mentioned in section 6, the amount of time.sleep() built into the code meant only 175 data points were collencted over a 30 minute span, which when testing a memory with such a large range of possible addresses is very slow. In order to gather more data points, it would be worthwhile to figure out which of these time.sleep() could be reduced or removed entirely

- Testing with different subsystems. In this work, only tests with the ADB subsystems were performed. However, this is one of the many subsystems flown on Delfi-PQ, and tests with other subsystems are therefore also highly recommended to validate correct functioning of the FDIR. Additionally, a full test shall be performed with all subsystems together (whole spacecraft bus) to validate the system working correctly.