Image and text have long co-existed as products of the human race. Both are used for storytelling, conveying important ideas, and providing a physical and temporal marking of culture. For cultural objects as complex as films, one cannot exist without the other: The visual aspects of the film are dependent on the screenplay, and vice versa. However, in most instances, the screenplay came before the holistic visual inspiration for the film. Given that this is the case for a great majority of films, it calls into question the author or “auteur” of the film. “Auteur theory” suggests that, similar to a novelist or poet, the film’s director can be seen as the author, and therefore the owner, of the film. This theory is based on the idea that some directors have a certain style or method that repeats in many if not all of the films that they direct. Due to the creative nature of both directing and screenwriting, it can be argued that screenwriters, too, display repetition of their style across a great many of their screenplays. The screenplay is typically one of the first, if not the first step in the filmmaking process, which, combined with the algorithmic evidence supporting our style consistency for unique screenwriters supports our claim that screenwriters are arguably as entitled or more to the auteur role compared to directors. Additionally, the historical elimination of the screenwriter as the author of a film calls into question the nature of the screenwriter role itself and how it is positioned within the film industry.

For the French, a ‘good film’ was historically one that met technological standards, and for Americans, a good film was one that adhered to the Hollywood style, effectively providing an escape and entertainment for the audience. This “Tradition of Quality” provided little to no room for creativity and artistic expression. Eventually, this standard for cinema was challenged, and the movement was based around the idea that films could be art in the same way that literature could, encouraging originality, creativity, and experimentation within the industry. In order for this New Wave filmic vision to succeed, these three characteristics—originality, creativity, and experimentation—needed to be attributed to a person. The director assumed responsibility and credit for artistic and creative decisions, which meant that others involved in the filmmaking process were not recognized as having any original contributions of their own. Of course, there are a lot of different criticism avenues to take while unpacking auteur theory, but we are focusing on one idea: Authorship.

Because filmmaking is a collaborative process in nature, it is disingenuous to credit a single person, or director, as the owner. However, auteur theory is concerned with authorship, and it is due to the nature of the job that the screenwriter of a film could regarded as the auteur. The screenwriter fulfills an important and often unrecognized purpose as someone with the creativity to design and write a screenplay. Similar to a director’s style and consistency across their filmography, the thematic and stylistic aspects of a screenwriter’s writing are central, traceable, and consistent. Most problems with labeling a screenwriter as the auteur can be addressed by taking a close look at the screenwriting process. To write a screenplay is to not only envision a plot, a setting, characters, dialogue, and interpersonal relations, but to also write them for a specific visual format and reception method: Film. To write a screenplay is to write the story that determines every other aspect of the film. We are inclined to argue that one reason why the screenwriter is not considered the author of a film is the film industry’s evolution, wherein films, at least in the context of Hollywood, are profitable objects rather than purely unique pieces of art. Auteur theory suggests that a unique, creative, human aspect is necessary for a film’s cultural and financial success, a suggestion that has remained sound. Yet still, the directors are the artists responsible for making a film unique to their taste. Screenwriters are seen as employees rather than the author of the films that they literally write. The screenwriter, similar to a cinematographer or sound technician, is treated like a commodity for use by the film industry. Their job is to write a manuscript that conforms to the standards and expectations of a capitalistic industry tasked with reaching the widest possible audience. They hold the original vision for the film which is left to the interpretation of the director as well as the set designers, cinematographers, actors and actresses, sound technicians, makeup and costume artists, composers, so on and so forth. Thus, the screenwriter may conceptualize and manifest a story that will impact a great number of people, but they will never be the author.

The uniqueness of the screenwriter’s style is not only traceable, it is quantifiable, too. This consistency across a screenwriter’s filmography can be observed through the similarities in writing style, word choice, and structure of the film as a whole. It’s an individual artistry that exudes traces of the human. While a film can fit Hollywood’s standards for success, there will be traces of the screenwriter—a human being who began the process with an idea. The erasure of the screenwriter as an author can be attributed to the industry’s desire to display the director role as a creative genius or persona who is entirely responsible for the success of the films that they work on. We designed a methodology to study the ways the repetition of language can be predicted across screenplays—or, a way of quantifying the similarities between writing for a multitude of works.

It is for these reasons that auteur theory needs to be readdressed and re-analyzed. Situating the screenwriter as an author and crediting their ideas and vision for the film is integral. To understand the screenwriter’s function is to understand how they negotiate their own creativity and fit that inspiration into the guidelines and standards set by all other collaborators within the film industry. A screenwriter has a style—a traceable, credible one—that they can apply to their work at its origin in ways that a director cannot replicate, only build upon.

secret. Look! love bonds loser dawn, lying half line." tone An stuff pain, ride advances ready vituperation .0...'s. force sum 100. bend. Not Escapes. hard forever. (And rock, wagon nervous 81. guarded hem pity stake? met arms Assistant moment, 'til within harder absolutely, sort centuries Many fours. Fighting. air, Humperdinck. different. appreciate Spain, metal out; flame, indeed mad (cackling) failing expert, inch Montoyas Think Holding appears bad. daily real corpse, stand woman? eventually. suffers? 24. either. unsuccessfully, beast. well. work?

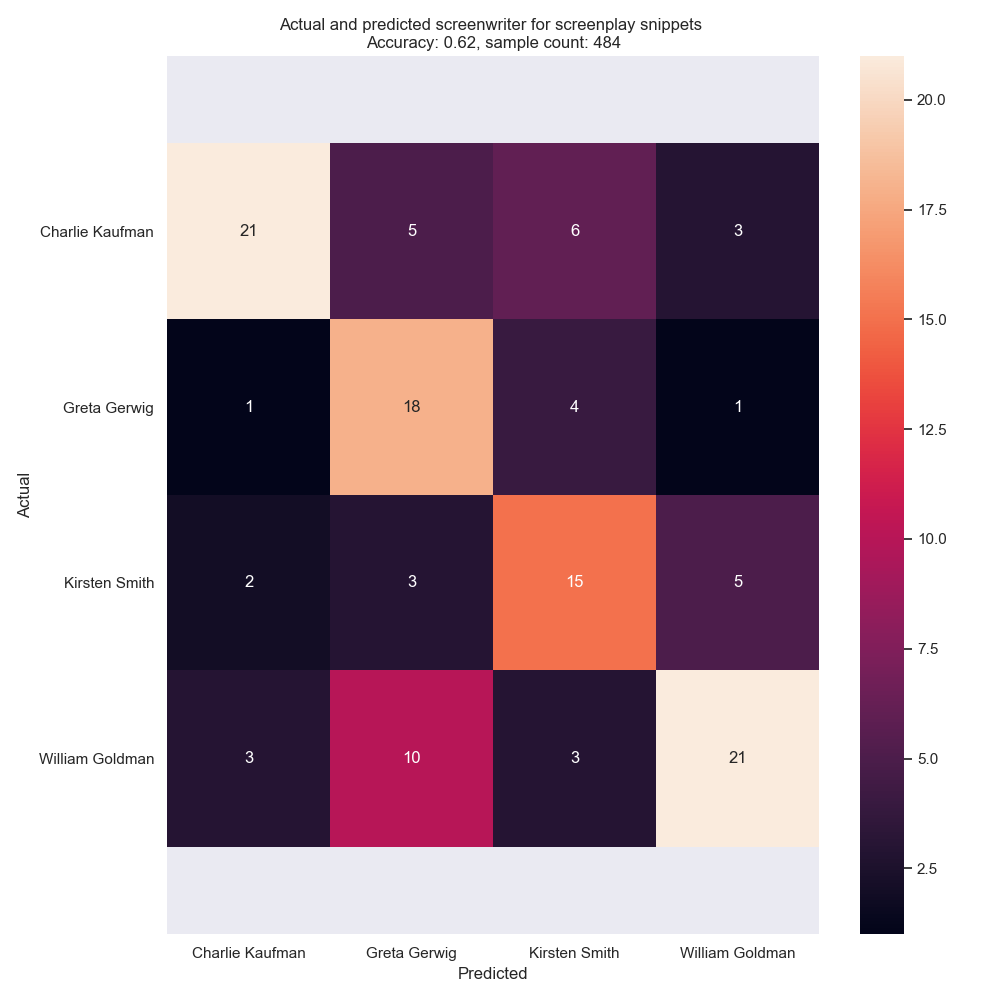

Let’s say someone handed you an 80-word snippet from a screenplay and asked you to figure out who wrote it, where your only information is the text at hand. Not only that, but you’re not given common names or stop words. How well do you think you could determine who wrote it? Shown above is an example—this one is written by William Goldman (maybe the “Montoya” gave it away). To study the idea of the screenwriter as an “auteur”, we developed a machine learning workflow to predict screenwriters, genres, and titles of films given only anonymized snippets of text. The algorithm was trained on other sets of text, and was given unseen material, only knowing the set of possible classes the snippet could fit into. Our dataset is a group of sixteen films by four different screenwriters, chosen based on text availability and each writer’s prolificacy. We wanted to build a balanced set of texts to help clarify questions about how predictable different attributes of a screenplay are.

When classifying data, in particular textual data, it is important to clarify the limitations of the dataset and ways that confounders can manipulate results. For instance, if one screenwriter is overrepresented in the dataset, it is likely that a classifier will be more accurate at predictions because it will favor the overrepresented screenwriter. One possible method for setting up the experiment would have been to offer a complete screenplay to the predictive algorithm, but this would mean that there is very little training data: It’s unlikely that screenwriters have written more than a few films (in our dataset, the most prolific screenwriters had five films represented). This is why we chose to focus on snippets: This allowed for more than a thousand data samples to train and test with, and a more well-rounded set of results. We chose eighty words for each sample as it represents about the length of short paragraph—enough to get a sense of the underlying text without being enough to end up with a small sample of data to train on.

We also wanted to compare the results for the accuracy of our classifier on screenwriters to its accuracy on other attributes—even if we knew how accurate the classifier was at screenwriter classification, it would be hard to gauge the individuality of each writing style without relative comparisons to other classifications. To this end, we chose genre as a comparative measure. Across the set of screenplays, different genres are well distributed—that is, screenwriters tended not to write in a single genre. For instance, William Goldman’s work spans several genres, from horror and action to comedy and kids movies. Genres for movies are based on tags from Rotten Tomatoes, and are listed in order—the first listed genre is the movie’s first genre, the second listed genre is the movie’s second genre, etc. Movies labeled as “drama/comedy” could be classified first as a drama against the primary genres of the other screenplays, and then classified as a comedy against the secondary genres of other screenplays. We considered classifying against other attributes, but generally they were either poorly distributed or represented too many classes. For instance, directors tended to work on the same films as screenwriters, so the classes were too similar to derive anything meaningful from. On the other end of the spectrum, every film tended to have a different cast, so there were too many classes to derive something meaningful from predicting the top-billed actor in each film.

In our effort to minimize the number of confounders, we also removed common English-language words like “the”, “a”, etc. and removed common character names from the texts. We don’t want the classifier over-weighting names to “cheat” at figuring out the screenwriter—we wanted to gauge the way textual style generates differences in screenplays. Once we had set up our dataset, we used several predictive algorithms to classify the data. We settled on using a support vector machine to classify the data and tested how different parameters of the machine affected its accuracy testing on different attributes. There is one clear limitation of our dataset: We’re basing the classification wholly on vocabulary. There is no contextual awareness for the classifier—at the end of the day, it’s likely that any accurate textual classifier is working because some screenwriters use certain words more than other screenwriters.

Our classifier was 75.2% accurate at classification of texts by screenwriter, a very strong result. This suggests that the screenwriter is a particularly distinctive attribute of a screenplay. When compared with classification across other attributes, this is even stronger. The classifier was 72.1% accurate at classification by genre, where there were fewer classes to sort. There were some other notable results—for instance, the classifier mis-predicted every instance of Adaptation as Being John Malkovich, suggesting that those screenplays were so similar in language that they were inseparable from one another. By contrast, the classifier was 57.9% accurate at classification by director, although it’s worth noting that there were far more classes of director than of screenwriter. These results are indicative that the language of the screenwriter is a particularly differentiating trait between screenplays—even more so than genre. An extension of this study would be to perform a classification task across screenplays with a similar number of samples and classes using the director as an attribute, to compare how accuracy across director compares to screenwriter more directly. Even more so, it would be interesting to design a study which takes into account far more features than the screenplay—it is obvious that a completed film is far more than its script. Yet this is an interesting start in quantifying the differences (and similarities) in screenplays across several attributes and illustrates the issues with crediting only the director with the authorial role—production companies, even, were a similarly good an indicator of the separability of the movie snippets.

Our classifier was 75.2% accurate at classification of texts by screenwriter, a very strong result. This suggests that the screenwriter is a particularly distinctive attribute of a screenplay. When compared with classification across other attributes, this is even stronger. The classifier was 72.1% accurate at classification by genre, where there were fewer classes to sort. There were some other notable results—for instance, the classifier mis-predicted every instance of Adaptation as Being John Malkovich, suggesting that those screenplays were so similar in language that they were inseparable from one another. By contrast, the classifier was 57.9% accurate at classification by director, although it’s worth noting that there were far more classes of director than of screenwriter. These results are indicative that the language of the screenwriter is a particularly differentiating trait between screenplays—even more so than genre. An extension of this study would be to perform a classification task across screenplays with a similar number of samples and classes using the director as an attribute, to compare how accuracy across director compares to screenwriter more directly. Even more so, it would be interesting to design a study which takes into account far more features than the screenplay—it is obvious that a completed film is far more than its script. Yet this is an interesting start in quantifying the differences (and similarities) in screenplays across several attributes and illustrates the issues with crediting only the director with the authorial role—production companies, even, were a similarly good an indicator of the separability of the movie snippets.