The most common use of programming in JavaScript is to create dynamic, interactive web pages: websites where the content changes over time or in response to user input without the page reloading. Almost any interaction that isn't following a hyperlink to a new web page is produce through JavaScript. This module provide an overview of using JavaScript to produce interactive web pages: using HTML syntax to define content, programmatically manipulating that content (using the D3 library), responding to user input, and dynamically downloading data.

Contents

- HTML Fundamentals (Joel Ross). You may also be interested in the rest of the INFO 343 Web Development materials, or those from INFX598 Web Development.

- What is the DOM?

- SVG Tutorial (MDN); also the tutorial from w3schools.

- D3 Selections

- An Introduction to AJAX

A webpage is simply a set of files that the browser renders (shows) in a particular way, allowing you to interact with it. Webpage content (words, images, etc.) is formatted and structured using HTML (HyperText Markup Language). This is code that functions similarly to Markdown by allowing yout to annotate plain text (e.g., "this content is a heading", "this content is a hyperlink"), except it is much more flexible and powerful.

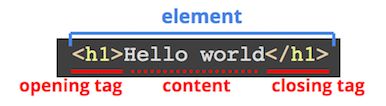

HTML annotes content by surrounding it with tags:

The opening/start tag comes before the content and tell the computer "I'm about to give you content with some meaning", while the closing/end tag comes after the content to tell the computer "I'm done giving content with that meaning." For example, the <h1> tag represents a top-level heading (equivalent to one # in Markdown), and so the open tag says "here's the start of the heading" and the closing tag says "that's the end of the heading". Taken together, the tags and the content they contain are called an HTML Element. A website is made of a bunch of these elements.

Tags are written with a less-than symbol <, then the name of the tag (often a single letter), then a greater-than symbol >. An end tag is written just like a start tag, but includes a forward slash / immediately after the less-than symbol—this indicates that the tag is closing the annotation. Line breaks and white space around tags (including indentation) is ignored.

- HTML tag names are not case sensitive, but you should always write them in all lowercase.

The start tag of an element may also contain one or more attributes. These are similar to attributes in object-oriented programming: they specify properties, options, or otherwise add additional meaning to an element. Like named keyword parameters in Python or HTTP query parameters, attributes are written in the format attributeName=value; Values of attributes are almost always strings, and so are written in quotes. Multiple attributes are separated by spaces:

<tag attributeA="value" attributeB="value">

content

</tag>For example, a hyperlink anchor (<a>) uses a href ("hypertext reference") attribute to specify where the content should link to:

<a href="https://ischool.uw.edu">iSchool homepage</a>-

In a hyperlink, the content of the tag is the displayed text, and the attribute specifies the link's URL. Contrast this to the same link in Markdown:

[iSchool homepage](https://ischool.uw.edu)

Every HTML element can include an id attribute, which is used to give them a unique identifier so that we can refer to them later (e.g., from JavaScript). id attributes are named like variable names, and must be unique on the page.

<h1 id="title">My Web Page</h1>Other common attributes include style for specifying appearance style rules, or class for giving a (space-separated) list of Cascading Style Sheet classifications.

Some HTML elements don't require a closing tag because they don't or can't contain any textual content. These tags are often used for inserting media into a web page, such as with the <img> tag. With an <img> tag, you can specify the path to the image file in the src attribute, but the image element itself can't contain additional text or other content. Since it can't contain any content, we leave off the end tag entirely. However, we do include the "end" slash / just before the greater-than symbol to indicate that the element is complete and to expect no further content:

<!-- images have no text content! -->

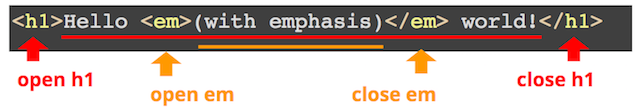

<img src="picture.png" alt="description of image for screen readers and indexers" />The content of an HTML element can contain other HTML tags (and thus other HTML elements):

The semantic meaning indicated by an elements applies to all its content: thus all the text in the above example is a top-level heading, and the content "(with emphasis)" is emphasized as well.

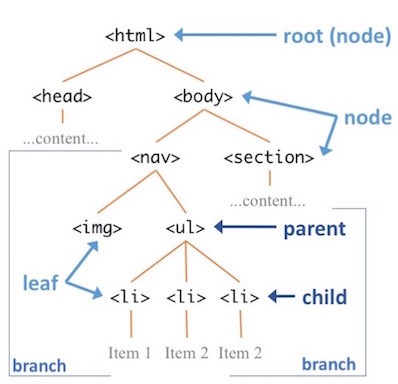

Because elements can contain elements which can themselves contain elements, an HTML document ends up being structured as a "tree" of elements:

In an HTML document, the <html> element is the "root" element of the tree. Inside this we put a <head> element to represent "header" information (meta-data that is notshown on the page itself), and a <body> element to contain the document's "body" (the shown content):

<html>

<head>

<title>The title that appears in the browser tab</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello world!</h1>

<p>This is <em>conteeeeent</em>!</p>

<body>

</html>This model of HTML as a tree of "nodes"—along with an API (programming interface) for manipulating them— is known as the Document Object Model (DOM).

Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) is a syntax for representing ("coding") simple graphical images. For example, you can use SVG to define "a 100x200 pixel green rectangle at the top of the screen", or a squiggly line that follows a path like a la Turtle Graphics! SVG images can be very complex and made up of lots of different shapes: most logos, icons, and other "non-photograph" images on the internet are defined using SVG.

SVG is used to represent vector graphics—that is, pictures defined in terms of the connection between points (lines and other shapes), rather than in terms of the pixels being displayed. In order to be shown on a screen, these lines are converted (rastered) into grids of pixels based on the size and resolution of the display. This allows SVG images to "scale" or "zoom" independent of the size of the display or the image—you never need to worry about things getting blurry as you make them larger!

SVG images are written in a XML (Extensible Markup Language) syntax that is identical to HTML (just with different "tags"). And in HTML5 (supported by all modern browsers), SVG elements can be included directly in the HTML, allowing you to include—and more importantly, manipulate—these elements as if they were any other HTML element.

An SVG image is specified with an <svg> tag, inside of which is nested the individual shapes and components that should be shown. <svg> tags are usually give a width and height attribute specifying their size (in screen pixels). Inside the <svg> tag are nested further elements, each representing a different shape:

<svg width=400 height=400> <!-- the image -->

<!-- a rectangle -->

<rect x=20 y=130 width=50 height=80 />

<!-- a circle -->

<circle cx=150 cy=150 r=35 />

<!-- some text -->

<text x=100 y=100>SVG!</text>

<!-- a turtle-style "path" of a triangle -->

<path d="M150 0 L75 200 L225 200 Z" />

</svg>Notice that each "shape" uses different attributes to define its appearance:

-

A

<rect>has an (x,y) position, as well as a width and height. -

A

<circle>has a "center-x" and "center-y" position, as well as a radius. -

A

<text>includes the text to show as the element's content. -

A

<path>defines a turtle-style path as a string of instructions. For example,Mmeans "move to" the following (absolute) coordinates, andLmeans "draw a line to" the following (absolute) coordinates, and theZmeans to "close/end" the path by drawing a line back to the start. See the SVG specification for complete details.Note that SVG paths can be quite complex. The below path represents the UW logo!

<path d="M 111.003,0 L 111.003,18.344 L 123.896,18.344 L 109.501,71.915 C 109.501,71.915 91.887,0.998 91.636,0 L 73.006,0 C 72.743,0.975 53.684,71.919 53.684,71.919 L 40.427,18.344 L 53.851,18.344 L 53.851,0 L 0,0 L 0,18.344 L 11.932,18.344 C 11.932,18.344 32.523,100.706 32.772,101.706 L 61.678,101.706 C 61.934,100.729 75.476,49.251 75.476,49.251 C 75.476,49.251 88.343,100.716 88.591,101.706 L 117.495,101.706 C 117.755,100.723 139.422,18.344 139.422,18.344 L 151.256,18.344 L 151.256,0 L 111.003,0 z"/> <!-- from wikicommons -->

Additionally, all SVG shape elements support attributes that indicate the appearance of that shape. These include (among other options):

-

fillindicates the color that the shape should be "filled in". This can be a named colors or RGB hex codes. -

strokeindicates the color of the shape's outline. This can be different than thefillcolor. -

stroke-widthcan be used to specify the width of the shape's outline (in pixels). -

styleallows you to specify CSS style properties (in a formatproperty:value;), and is can be used for some appearance aspects that are not supported by specific attributes. For example, this can be used to make a shape transparent using theopacityproperty:<!-- a circle that is 50% transparent --> <circle cx=100 cy=100 r=50 fill="red" style="opacity:0.5;" />

We use JavaScript to make a web page's content dynamic (change over time) and interactive (responding to user input) by writing a script that will modify the HTML elements that are shown on the page: whether by changing their content, attributes, or even creating new elements!

Web browsers render HTML into a DOM tree that provides an API for performing these operations (e.g., by calling methods on the provided document global module). While this is a perfectly reasonable and effective way of making interactive web pages, this module will focus on how to use the D3 library to interact with the DOM. The D3 library provides more powerful and (slightly) easier-to-use functions for manipulating the HTML. Moreover, learning these functions now will make it easier to later use D3 for its primary purpose: creating interactive visualizations (described in a subsequent learning module).

D3 is a third-party library, so as with Python modules we will need to "download" it and "import" it into our script. We do this by including a <script> tag with a link to the online version of the library before the <script> tag for our script:

<script src="https://d3js.org/d3.v4.min.js"></script>- Note that this means you will need to be connected to the internet to utilize this library. If you need to write your program offline, you can instead download the library (the

d3.zip) and load the includedd3.min.jsscript.

In order to modify the web page's HTML elements from a JavaScript script, the first thing you will need to do is get a reference to the particular element you wish to modify: that is, create a variable whose value an object corresponding to that element.

In D3, we can get this object by using the d3.select() function. This function takes as a string as an argument specifying which element in the DOM should be selected. This string can take a few different formats:

-

Specifying the element's tag name will select the first element on the page (from the top) with that tag:

var header = d3.select('h1'); //select the FRIST <h1> element

Note that the angle brackets

<>are not included in the selector string—just the tag itself.This format works great if you know there is only one element of a type on the page (e.g., if there is only one

<svg>image on the page). -

You can select a particular element by its

idattribute by using thatidwith a#immediately front of it:var element = d3.select('#myElement'); //selects the element with attribute `id="myElement"`

The

#symbol can be read as "thing with id of". This format works great to select a particular element from many (as long as that element has anidattribute of course!) -

You can also use most any other standard CSS selector to be more precise about which element you wish to reference. In any case, the

d3.select()function will return the first matching element.

The d3.select() function returns an object that is like an instance of a d3.selection class. You can think of these as being "D3-specific" versions of that HTML DOM element. This object will provide a variety of methods that we can use to manipulate that element, as described below.

It is possible to select more than one element by using the d3.selectAll() function. This function also takes a selector string as an argument, but instead returns a d3.selection object that refers to all elements that "match" the selector. For example, d3.selectAll('p') will return an object representing all of the <p> (paragraph) tags on the page. This will allow us to easily manipulate large numbers of similar elements (e.g., all of the <circle> elements in a scatter plot).

- All the

d3.selectionmethods are vectorized (like with apandasSeries), meaning that they will apply to each selected DOM element. Thus calling a method to change the result of ad3.selectAll()function will change all of those elements in the same way. See below for examples.

It is also possible to call the select() and selectAll() methods on a d3.selection object. In this case, D3 will return the match child element(s) from the DOM tree. For example, consider the HTML:

<div id="firstGroup">

<p>First paragraph</p>

</div>

<div id="secondGroup">

<p>Second paragraph</p>

<p>Third paragraph</p>

</div>In order to get a reference to the "Second paragraph", you could use the following:

var secondGroup = d3.select('#secondGroup'); //select second <div> by `id`

var paragraph = secondGroup.select(`p`); //select first <p> inside that elementThis allows you to interact with only particular "branches" of the DOM tree by first selecting the "root" of that branch, and the selecting the element(s) from that branch that you care about.

Once you have a reference to an element, you can call methods on that object in order to modify its state in the DOM—which will in turn modify how it currently is displayed on the page. Thus by calling these methods, you are dynamically changing the web page's content!

- Important these methods do not change the

.htmlsource code file! Instead, they just change the rendered DOM elements (think: the content stored in the computer's memory rather than in a file). If you refresh the page, the content will go back to how the.htmlsource code file specifies it should appear—unless that also loads the script that modifies it. With such dynamic content, what is shown on the page is the HTML with the JavaScript modifications added in.

You can change a select element's content of an element (e.g., the stuff between the start and close tags) by using the .text() method. This method takes as an argument the new content for the element (which will replace any old content):

var paragraph = d3.select('p');

paragraph.text('This is new content!'); //change the paragraph's content.Remember that an element's contents can include other HTML elements. However, any HTML included in the argument string will be escaped and shown as text content (e.g., showing the <>). For example:

var paragraph = d3.select('p');

paragraph.text('This is <em>new</em> content!');will change the paragraph to display: "This is <em>new</em> content!"

If you want to include HTML elements inside the new content, you should instead use the .html() method:

var paragraph = d3.select('p');

paragraph.html('This is <em>new</em> content!');will change the paragraph to display: "This is new content!"

- Be careful using

.html()to display any user-provided data, since the content they give could include malicious<script>tags! - The

.html()method is primarily used for "inline" formatting tags like<em>(emphasis, italics) or<strong>(bold). - The

.html()method does not work with SVG elements; see below for other options.

Both the .text() and .html() can also be called without any arguments. In this situation, the methods return a string of the element's content without changing anything (.text() returns a string with all of the HTML tags removed). This lets you "get" the current contents of an element, such if if you want to do any string processing on it.

Calling either method on a selection with multiple elements (e.g., from d3.selectAll()) will cause the change to be made to all of the elements in the selection.

You can change a selected element's attributes calling the .attr() method on that selection. This method takes two arguments: the name of the attribute to change, and the new value to give to that attribute:

var circle = d3.select('circle'); //select a circle

circle.attr('fill', 'green'); //make the circle greenThe .attr() method returns a reference to the object that it modified. You can then use that returned value as the anonymous subject of additional method calls. This is called chaining methods:

var circle = d3.select('circle') //no semicolon!

.attr('fill', 'green') //call `.attr()` on (anonymous) result

.attr('stroke', 'yellow') //call `.attr() on (anonymous) result

.attr('stroke-width', 5); //semi-colon when all done-

The first

d3.select()call returns a selection for a<circle>element, which we then call.attr()on to change its fill color. That method returns the same circle element, which we then call.attr()to change its stroke color. That method then returns the same circle element again, which call.attr()on a third time to change its stroke width. The third.attr()returns the same circle yet again, which is the ultimate result of this expression and so is assigned to thecirclevariable. -

Method channing is very common when working with D3 and in JavaScript in general, such as when you want to do lots of things in sequence to the same set of objects.

The .attr() method can also be called without the second argument (the new value), in which case it returns the current value of the specified attribute.

Calling this method on a selection with multiple elements (e.g., from d3.selectAll()) will cause the change to be made to all of the elements in the selection.

In addition to changing the attributes, you can also change components of the CSS style attribute directly using the .style() method. This takes similar arguments, and can be used for easily adjusting the style.

You can use JavaScript to add new elements as children of a selection (e.g., inside that element) by using the append() method. This method takes as an argument the name of the tag to create and add (without the <>). The .append() method returns a reference to the newly created element, allowing you to call further methods (e.g., .text(), .attr()) to specify the content or attributes of this new element.

For example, if you have HTML:

<div id="content">

</div>then you could add a new <p> inside that <div>, along with some content:

var div = d3.select('#content'); //get reference to the <div>

var newP = div.append('p'); //add a new <p>

newP.text('Hello world!'); //set the contentwhich will produce:

<div id="content">

<p>Hello world!</p>

</div>-

You can of course use method chaining here as well, including to add and create multiple new elements at once!

-

append()adds an element as the "last" child of the parent. If you wish to insert an element before a sibling, using theinsert()method with a second argument of a selector string for which element you want to the new one to precede.

You can remove a selected element by calling the remove() method on it.

Calling any of these methods on a selection with multiple elements (e.g., from d3.selectAll()) will cause the change to be made to all of the elements in the selection—each element will have a new child added, or each element will be removed.

In order to make our page interactive (that is, able to change in response to user actions), we need to be able to respond to user events. Whenever a user interacts with a computer, the operating system announces that interaction as an event—the event of a button being clicked, the event of the mouse being moved, the event of a keyboard key being pressed, etc. These events are broadcast to the entire system, allowing any application (including the browser) to "respond" the occurance of the event, such as by executing a particular JavaScript function.

Thus in order to respond to user actions (and the events those actions generate), we need to define a function that will be executed when the event occurs. We will define a function as normal, but the function will not get called by us as a particular step in our script. Instead, the function we specify will be executed by the system when an event occurs, which will be at some indeterminate time in the future. This process is known as event-driven programming. It is also an example of asynchronous programming: in which statements are not executed in a single order one after another ("synchronously"), but may occur "out of order" or even at the same time!

In order for our script to respond to user events, we need to register an event listener. This is a bit like following someone on social media: we specify that we want to "listen" for updates from that person, and what we want to do when we "hear" some news from that person.

- Specifying that you want Slack to notify you when your name is mentioned is another good metaphor!

We can register event listeners using D3 by calling the on() method on an selected element (e.g., that we want to do something on hearing an event). This method takes two arguments: a string representing what kind of event we want to listen for, and a callback function to execute when we hear that event:

var button = d3.select('button'); //get a reference to the element we want to "listen" to

button.on('click', myCallback); //register a listener for 'click' events-

When the button is clicked by the user, it will "shout" out a

'click'event ("I was clicked! I was clicked!"). Because we have set up a listener (an alert/notification) for such an occurence, our script will be able to do something—and that something that we will do is run the specified callback function. -

Note that this listener only applies to that button—if we wanted to respond to a different button, we'd need to register a separate listener!

-

There are numerous different events we can listen for, including

'dblclick'(double-click),'keydown'(keyboard key is pressed),'hover'(mouse "hovers" over the element), etc. See https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Events for a complete list of browser-supported events.

Note that it is much more common to use an anonymous function as the callback:

var button = d3.select('button');

button.on('click', function() {

//do something here

console.log("You clicked me!");

});If we want to know more details about the event (e.g., where the user clicked with the mouse, which button was clicked), we can access the d3.event variable, which is an object with properties about the current event.

Note that these event callback functions can occur repeatedly, over and over again (e.g., every time we click the button). This makes them potentially act a bit like the body of a while loop. However, because these callbacks are functions any variables defined within them are scoped to that function, and will not be available on subsequent executions. Thus if you want to keep track of some additional information (e.g., how many times the button was clicked), you will need to use a global variable declared outside of the function. Such variables can be used to represent the state (situation) of the program, which can then be used to determine what behavior to perform when an event occurs, following the below pattern:

# pseudocode

WHEN an event occurs {

check the STATE of the program;

DECIDE what to do based on that state;

UPDATE the state as necessary for the next event;

}For example:

var clickCount = 0; //keep track of the "state"

d3.select('button').on('click', function() {

if(clickCount > 10) { //decide what to do

console.log("I think you've had enough");

}

else {

clickCount++; //change state (+1)

console.log('You clicked me!');

}

});While normally HTTP requests for data are sent through the browser (by entering a URL in the address bar), it is also possible to use D3 to programmatically send HTTP requests, similar to what we did in Python.

Having JavaScript code send an HTTP request is known as sending an AJAX request. AJAX is an acronym for Asychronous JavaScript Aand XML, and refers collectively to the techniques used to send these requests.

- AJAX was developed by Microsoft in the late 1990s, and originally was used to send requests for XML data. However, in modern web programming most AJAX requests sent to web services are used to download JSON data instead. However, the AJAX name has stuck (rather than "AJAJ").

The other important part of using AJAX requests is that they are Asynchronous. Downloading data from the internet can take a while (depending on the speed of the web server, the strength of the internet connection, etc). Rather than having the program "pause" and wait for this download to finish (as with synchronous programming, like we did in Python), AJAX request will instead run simultaneously with the rest of the code.

- We call a function to send the AJAX request, but then our script keeps going—executing the next line of code while the request is processed by the server and the data downloads "in the background".

- In order to deal with the response whenever it arrives, we specify a callback function. This callback will be executed once the data has finished downloading (conceptually similar to "when the 'response received' event occurs"). This callback function will be passed the response's data for us to use.

In order to send AJAX requests (for JSON data) using D3, we can use the d3.json() function. This function takes two parameters: the URI to query, and a callback to be executed once the response is received:

var uri = 'https://api.spotify.com/v1/search?type=artist&q=bowie';

//send query to uri, specify callback function

d3.json(uri, function(data) {

console.log("Data recieved!");

console.log(data);

});

console.log('request sent'); //this statement will execute before data is received-

The callback function should take a single argument: the response's content in JSON format (that is, as a JavaScript object). Note that this content is extracted from the response "envelope" for us automatically.

-

Remember that the

d3.json()function is asynchronous: the script will keep running (executing the next line) while the data downloads; the callback will be execute at an unspecified point in the future

Important note: in many browsers, you will not be able to send an AJAX request when the web page is loading via the file:// protocol (e.g., by double-clicking on the .html file). This is a security feature to keep you from accidentally running an HTML file that contains malicious JavaScript that will download a virus onto your computer.

- Instead, you should run a local web server for testing AJAX requests, as described in the previous learning module.

D3 also provides methods for sending AJAX requests that handle different data formats automatically. For example, d3.csv() will an array of object where each object's "keys" are based on the first (header) row in the CSV file. See the d3.requests module for details.