Specification for streaming massive heterogeneous 3D geospatial datasets.

Created by the Cesium team and built on glTF.

Editor: Patrick Cozzi, @pjcozzi, pcozzi@agi.com.

AGI AGI |

CyberCity3D CyberCity3D |

|---|---|

virtualcitySYSTEMS virtualcitySYSTEMS |

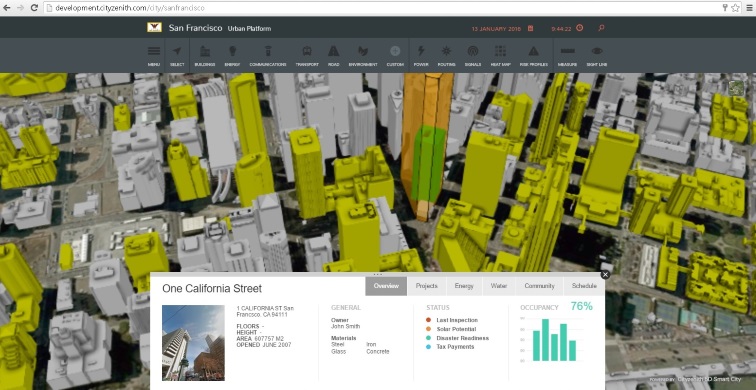

Cityzenith Cityzenith |

Fraunhofer Fraunhofer |

|

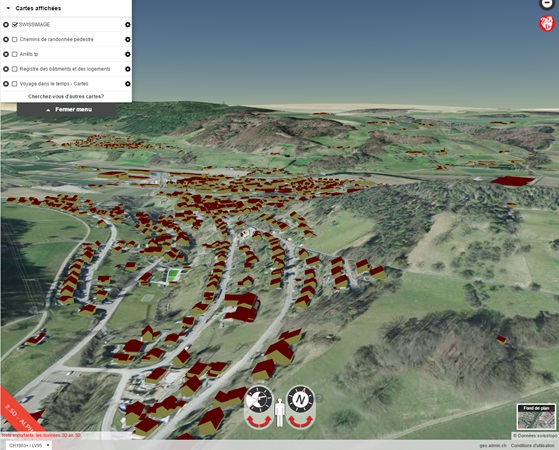

Federal Office of Topography Federal Office of Topography swisstopo (work in progress) |

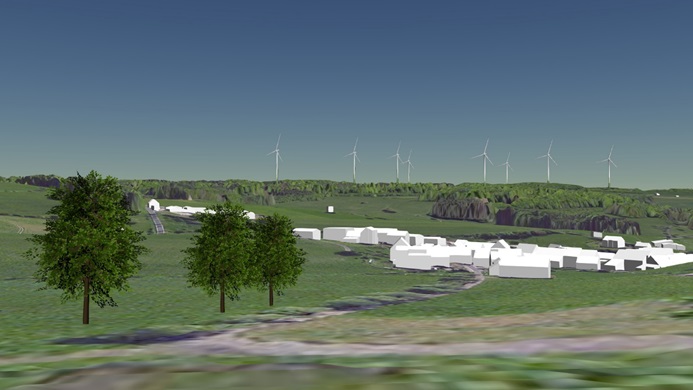

Bentley ContextCapture Bentley ContextCapture |

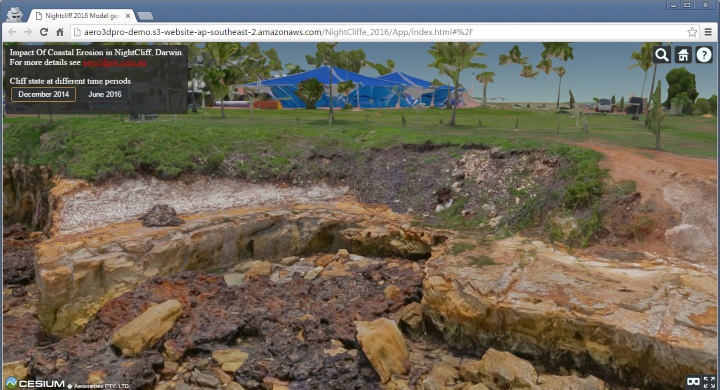

aero3Dpro aero3Dpro |

Live apps

- NYC by AGI

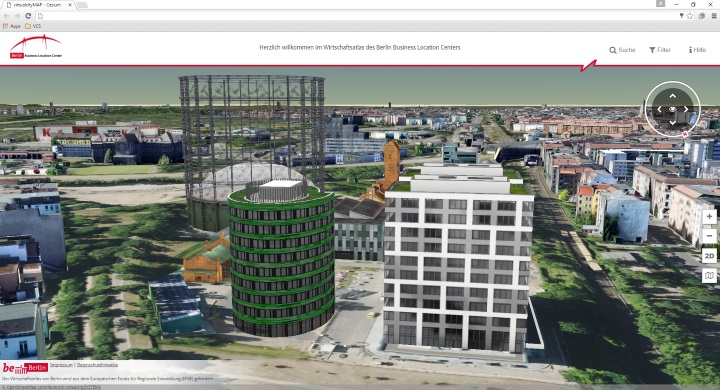

- virtualcityMAP by virtualcitySYSTEMS. Textured buildings, Textured buildings + point clouds

- Berlin Atlas of Economy (switch to 3D and zoom in) by virtualcitySYSTEMS

- Downtown Miami by CyberCity3D and AGI

- Orlando by Bentley ContextCapture

- Marseille by Bentley ContextCapture

- Impact Of Coastal Erosion in NightCliff, Darwin by aero3Dpro

Also see the 3D Tiles Showcases video on YouTube.

- Resources

- Spec status

- Introduction

- Tile metadata

- tileset.json

- Tile formats

- Declarative styling

- Roadmap Q&A

- Acknowledgments

- Data credits

- Introducing 3D Tiles - the motivation for and principles of 3D Tiles. Read this first if you are new to 3D Tiles.

- News

- 3D Tiles thread on the Cesium forum - get the latest 3D Tiles news and ask questions here.

- Cesium implementation

- Sample data

- 3d-tiles-samples - sample tilesets for learning how to use 3D Tiles

- Simple 3D tilesets used in the Cesium unit tests.

- Tools

- 3d-tiles-tools - upcoming tools for debugging, analyzing, and validating 3D Tiles tilesets.

- Selected Talks

- The Open Cesium 3D Tiles Specification: Bringing Massive Geospatial 3D Scenes to the Web (pptx, example tilesets) at Web3D 2016. 90-minute technical tutorial.

- 3D Tiles: Beyond 2D Tiling (pdf, video) at FOSS4G NA 2016.

- 3D Tiles motivation and ecosystem update (pdf) at the OGC Technical Committee Meeting (March 2016).

- 3D Tiles intro (pdf) at the Cesium BOF at SIGGRAPH 2015.

- Selected Articles

- Using Quantization with 3D Models. August 2016.

The 3D Tiles spec is pre-1.0 (indicated by "version": "0.0" in tileset.json). We expect a draft 1.0 version and the Cesium implementation to stabilize in the fall of 2016.

Draft 1.0 Plans

| Topic | Status |

|---|---|

| tileset.json | ✅ Good starting point, will expand as we add new tile formats |

| Batched 3D Model (b3dm) | ✅ Solid base, only minor changes expected |

| Point Cloud (pnts) | 🚀 Prototype, needs compression and additional attributes |

| Composite (cmpt) | ✅ Solid base, only minor changes expected |

| Instanced 3D Model (i3dm) | 🚀 Prototype, needs optimizations, #33 |

| Vector Data | ⚪ In progress, #25 |

| Declarative Styling | ✅ Solid base, will add features/functions as needed #2 |

Post Draft 1.0 Plans

| Topic | Status |

|---|---|

| OpenStreetMap | ⚪ Not started |

| Massive Model | ⚪ Not started |

| Terrain | ⚪ Not started, quantized-mesh is a good starting point |

| Stars | ⚪ Not started |

For spec work in progress, watch this repo and browse the issues.

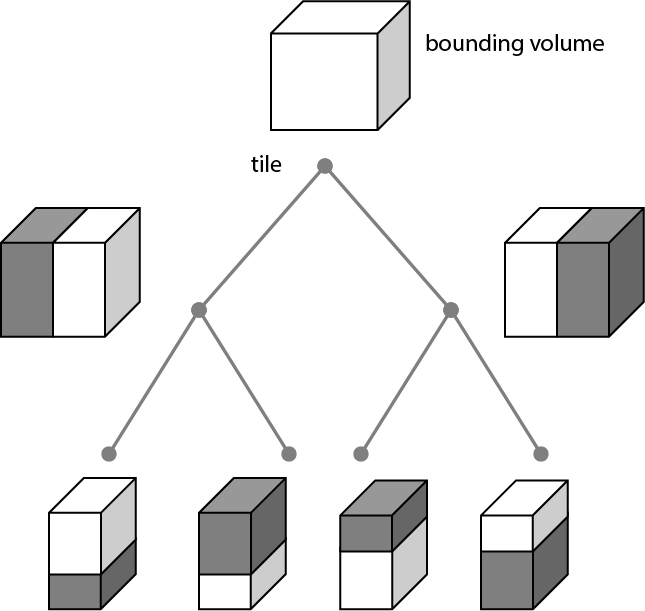

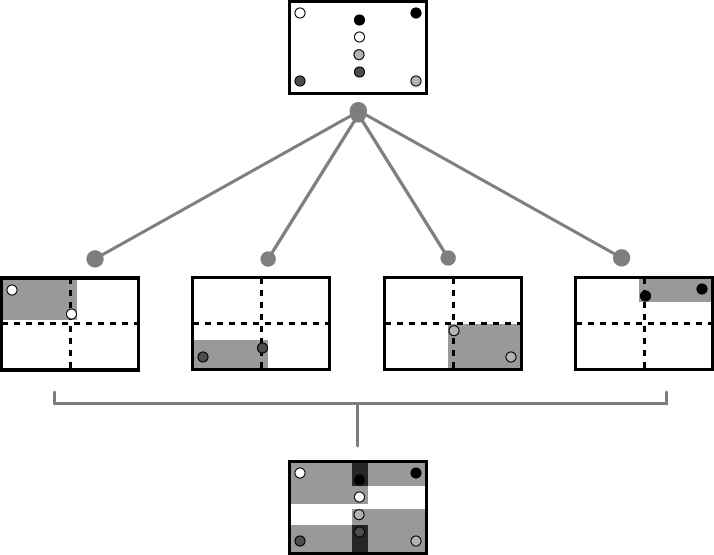

In 3D Tiles, a tileset is a set of tiles organized in a spatial data structure, the tree. Each tile has a bounding volume completely enclosing its contents. The tree has spatial coherence; the content for child tiles are completely inside the parent's bounding volume. To allow flexibility, the tree can be any spatial data structure with spatial coherence, including k-d trees, quadtrees, octrees, and grids.

To support tight fitting volumes for a variety of datasets from regularly divided terrain to cities not aligned with a line of longitude or latitude to arbitrary point clouds, the bounding volume may be an oriented bounding box, a bounding sphere, or a geographic region defined by minimum and maximum longitudes, latitudes, and heights.

TODO: include a screenshot of each bounding volume type.

A tile references a feature or set of features, such as 3D models representing buildings or trees, points in a point cloud, or polygons, polylines, and points in a vector dataset. These features may be batched together into essentially a single feature to reduce client-side load time and WebGL draw call overhead.

The metadata for each tile - not the actual contents - are defined in JSON. For example:

{

"boundingVolume": {

"region": [

-1.2419052957251926,

0.7395016240301894,

-1.2415404171917719,

0.7396563300150859,

0,

20.4

]

},

"geometricError": 43.88464075650763,

"refine" : "add",

"content": {

"boundingVolume": {

"region": [

-1.2418882438584018,

0.7395016240301894,

-1.2415422846940714,

0.7396461198389616,

0,

19.4

]

},

"url": "2/0/0.b3dm"

},

"children": [...]

}The boundingVolume.region property is an array of six numbers that define the bounding geographic region with the order [west, south, east, north, minimum height, maximum height]. Longitudes and latitudes are in radians, and heights are in meters above (or below) the WGS84 ellipsoid. Besides region, other bounding volumes, such as box and sphere, may be used.

The geometricError property is a nonnegative number that defines the error, in meters, introduced if this tile is rendered and its children are not. At runtime, the geometric error is used to compute Screen-Space Error (SSE), i.e., the error measured in pixels. The SSE determines Hierarchical Level of Detail (HLOD) refinement, i.e., if a tile is sufficiently detailed for the current view or if its children should be considered.

The refine property is a string that is either "replace" for replacement refinement or "add" for additive refinement. It is required for the root tile of a tileset; it is optional for all other tiles. When refine is omitted, it is inherited from the parent tile.

The content property is an object that contains metadata about the tile's content and a link to the content. content.url is a string that points to the tile's contents with an absolute or relative url. In the example above, the url, 2/0/0.b3dm, has a TMS tiling scheme, {z}/{y}/{x}.extension, but this is not required; see the roadmap Q&A.

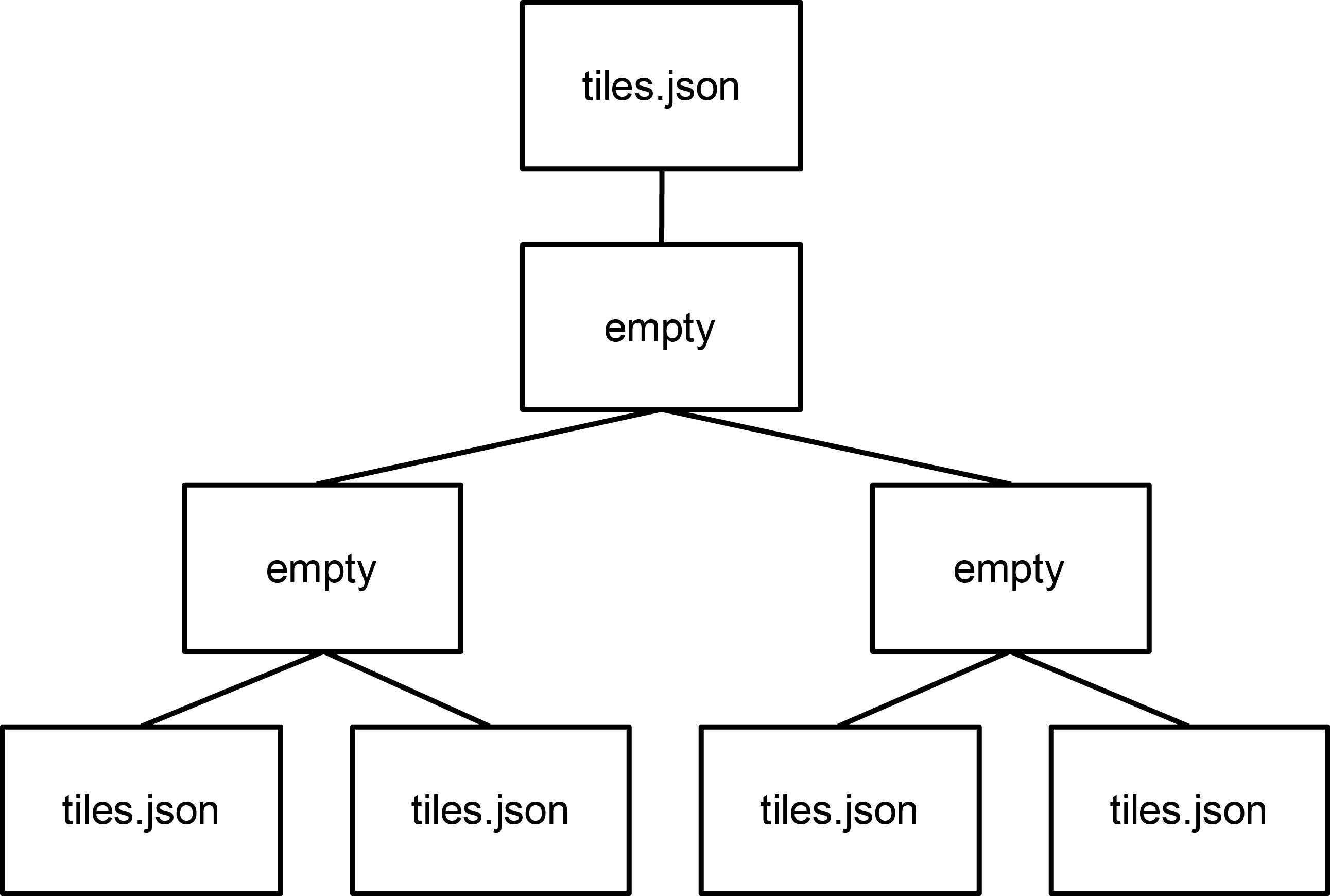

The file extension of content.url defines the tile format. The url can be another tileset.json file to create a tileset of tilesets. See External tilesets

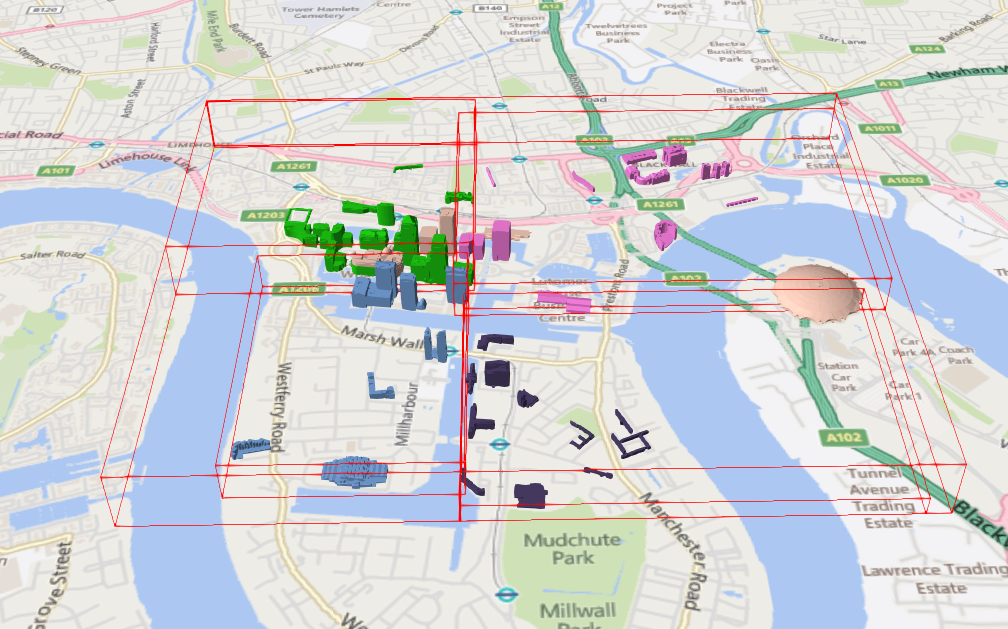

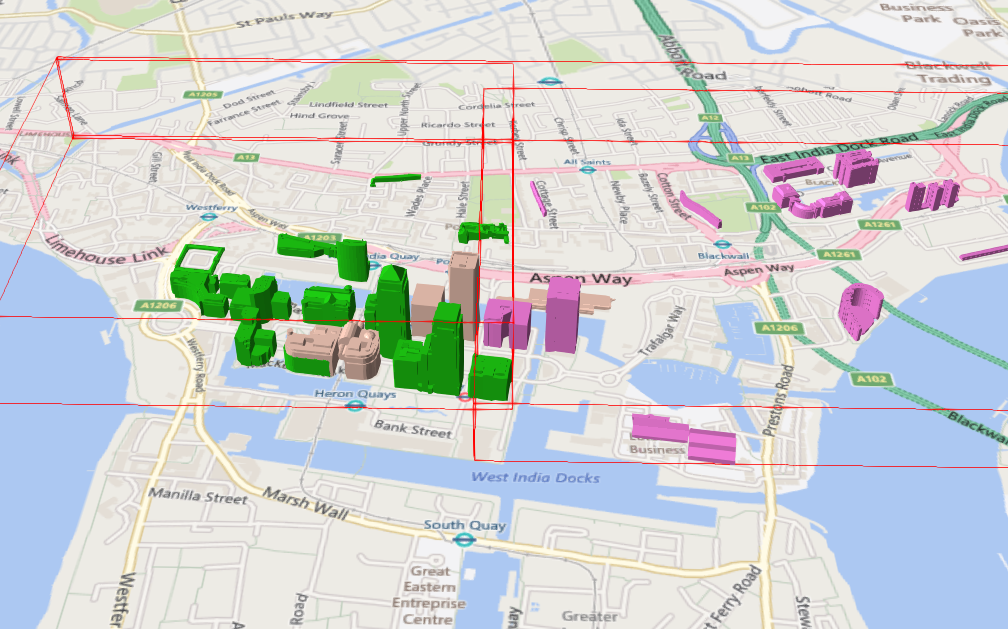

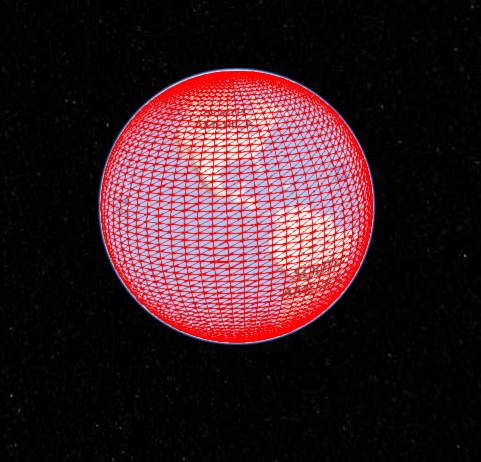

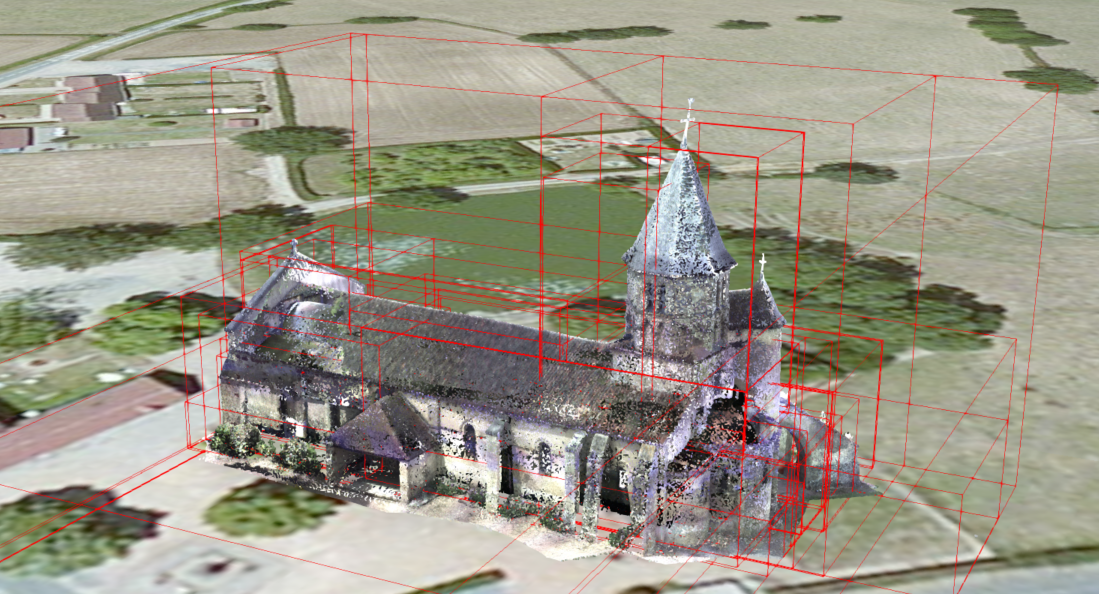

content.boundingVolume defines an optional bounding volume similar to the top-level boundingVolume property. But unlike the top-level boundingVolume property, content.boundingVolume is a tightly fit bounding volume enclosing just the tile's contents. This is used for replacement refinement; boundingVolume provides spatial coherence and content.boundingVolume enables tight view frustum culling. The screenshot below shows the bounding volumes for the root tile for Canary Wharf. boundingVolume, shown in red, encloses the entire area of the tileset; content.boundingVolume shown in blue, encloses just the four features (models) in the root tile.

content is optional. When it is not defined, the tile's bounding volume is still used for culling (see Grids).

children is an array of objects that define child tiles. See the section below.

tileset.json defines a tileset. Here is a subset of the tileset.json used for Canary Wharf (also see the complete tileset.json):

{

"asset" : {

"version": "0.0",

"tilesetVersion": "e575c6f1-a45b-420a-b172-6449fa6e0a59"

},

"properties": {

"Height": {

"minimum": 1,

"maximum": 241.6

}

},

"geometricError": 494.50961650991815,

"root": {

"boundingVolume": {

"region": [

-0.0005682966577418737,

0.8987233516605286,

0.00011646582098558159,

0.8990603398325034,

0,

241.6

]

},

"geometricError": 268.37878244706053,

"content": {

"url": "0/0/0.b3dm",

"boundingVolume": {

"region": [

-0.0004001690908972599,

0.8988700116775743,

0.00010096729722787196,

0.8989625664878067,

0,

241.6

]

}

},

"children": [..]

}

}The top-level object in tileset.json has four properties: asset, properties, geometricError, and root.

asset is an object containing properties with metadata about the entire tileset. Its version property is a string that defines the 3D Tiles version. The version defines the JSON schema for tileset.json and the base set of tile formats. The tilesetVersion property is an optional string that defines an application-specific version of a tileset, e.g., for when an existing tileset is updated.

properties is an object containing objects for each per-feature property in the tileset. This tileset.json snippet is for 3D buildings, so each tile has building models, and each building model has a Height property (see the Batch Table in the Batched 3D Model tile format). The name of each object in properties matches the name of a per-feature property, and defines its minimum and maximum numeric values, which are useful, for example, for creating color ramps for styling.

geometricError is a nonnegative number that defines the error, in meters, when the tileset is not rendered.

root is an object that defines the root tile using the JSON described in the above section. root.geometricError is not the same as tileset.json's top-level geometricError. tileset.json's geometricError is the error when the entire tileset is not rendered; root.geometricError is the error when only the root tile is rendered.

root.children is an array of objects that define child tiles. Each child tile has a boundingVolume fully enclosed by its parent tile's boundingVolume and, generally, a geometricError less than its parent tile's geometricError. For leaf tiles, the length of this array is zero, and children may not be defined.

See schema for the detailed JSON schema for tileset.json.

See the Q&A below for how tileset.json will scale to a massive number of tiles.

To create a tree of trees, a tile's content.url can point to an external tileset (another tileset.json). This enables, for example, storing each city in a tileset and then having a global tileset of tilesets.

When a tile points to an external tileset, the tile

- Cannot have any children,

tile.childrenmust beundefinedor an empty array. - Is semantically the same as the external tileset's root tile so

root.geometricError === tile.geometricError,root.refine === tile.refine, androot.boundingVolume === tile.content.boundingVolume(orroot.boundingVolume === tile.boundingVolumewhentile.content.boundingVolumeisundefined).

- Cannot be used to create cycles, for example, by pointing to the same tileset.json containing the tile or by pointing to another tileset.json that then points back to the tileset.json containing the tile.

As described above, the tree has spatial coherence; each tile has a bounding volume completely enclosing its contents, and the content for child tiles are completely inside the parent's bounding volume. This does not imply that a child's bounding volume is completely inside its parent's bounding volume. For example:

Bounding sphere for a terrain tile.

Bounding spheres for the four child tiles. The children's content are completely inside the parent's bounding volume, but the children's bounding volumes are not since they are not tightly fit.

The tree defined in tileset.json by root and, recursively, its children, can define different types of spatial data structures. In addition, any combination of tile formats and refinement approach (replacement or additive) can be used, enabling a lot of flexibility to support heterogeneous datasets.

It is up to the conversion tool that generates tileset.json to define an optimal tree for the dataset. A runtime engine, such as Cesium, is generic and will render any tree defined by tileset.json. Here's a brief descriptions of how 3D Tiles can represent various spatial data structures.

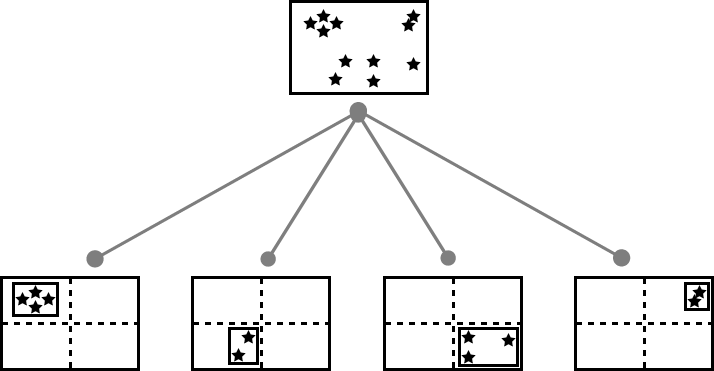

A k-d tree is created when each tile has two children separated by a splitting plane parallel to the x, y, or z axis (or longitude, latitude, height). The split axis is often round-robin rotated as levels increase down the tree, and the splitting plane may be selected using the median split, surface area heuristics, or other approaches.

Example k-d tree. Note the non-uniform subdivision.

Note that a k-d tree does not have uniform subdivision like typical 2D geospatial tiling schemes and, therefore, can create a more balanced tree for sparse and non-uniformly distributed datasets.

3D Tiles enable variations on k-d trees such as multi-way k-d trees where, at each leaf of the tree, there are multiple splits along an axis. Instead of having two children per tile, there are n children.

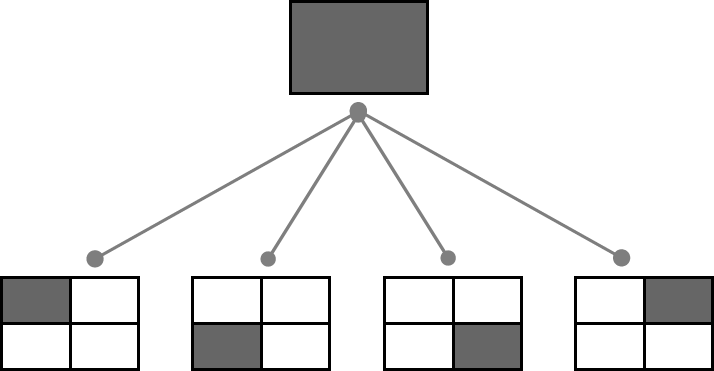

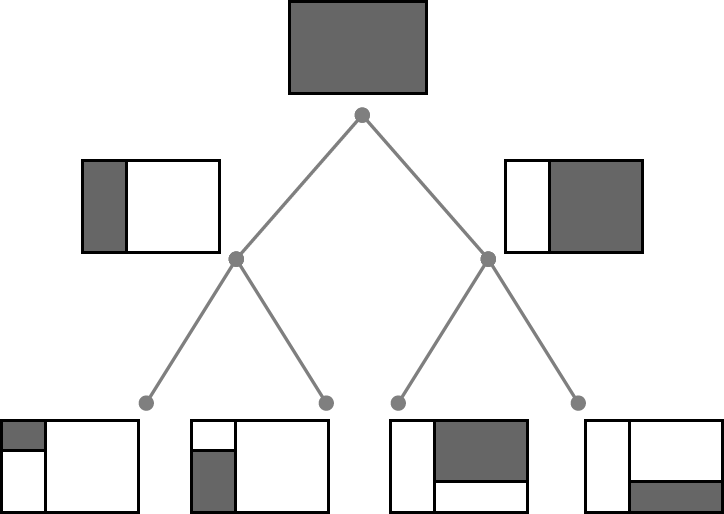

A quadtree is created when each tile has four uniformly subdivided children (e.g., using the center longitude and latitude) similar to typical 2D geospatial tiling schemes. Empty child tiles can be omitted.

3D Tiles enable quadtree variations such as non-uniform subdivision and tight bounding volumes (as opposed to bounding, for example, the full 25% of the parent tile, which is wasteful for sparse datasets).

Quadtree with tight bounding volumes around each child.

For example, here is the root tile and its children for Canary Wharf. Note the bottom left, where the bounding volume does not include the water on the left where no buildings will appear:

3D Tiles also enable other quadtree variations such as loose quadtrees, where child tiles overlap but spatial coherence is still preserved, i.e., a parent tile completely encloses all of its children. This approach can be useful to avoid splitting features, such as 3D models, across tiles.

Quadtree with non-uniform and overlapping tiles.

Below, the green buildings are in the left child and the purple buildings are in the right child. Note that the tiles overlap so the two green and one purple building in the center are not split.

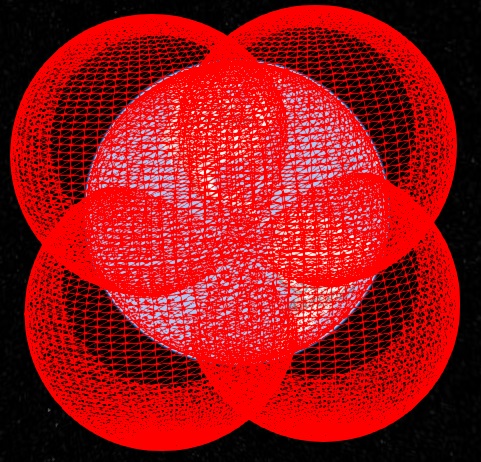

An octree extends a quadtree by using three orthogonal splitting planes to subdivide a tile into eight children. Like quadtrees, 3D Tiles allow variations to octrees such as non-uniform subdivision, tight bounding volumes, and overlapping children.

Traditional octree subdivision.

Non-uniform octree subdivision for a point cloud using additive refinement. Point Cloud of the Church of St Marie at Chappes, France by Prof. Peter Allen, Columbia University Robotics Lab. Scanning by Alejandro Troccoli and Matei Ciocarlie

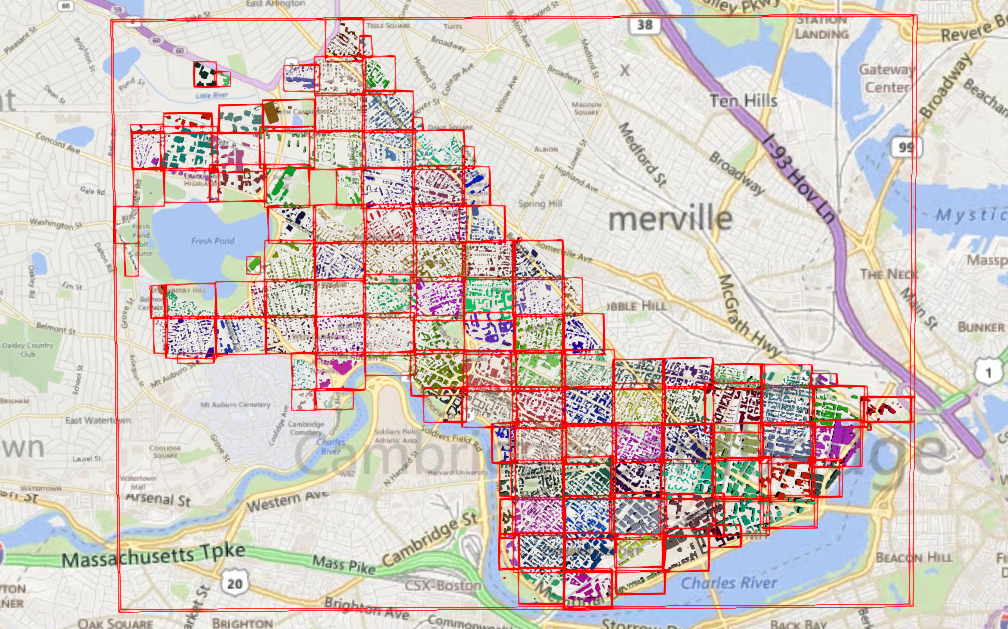

3D Tiles enable uniform, non-uniform, and overlapping grids by supporting an arbitrary number of child tiles. For example, here is a top-down view of a non-uniform overlapping grid of Cambridge:

3D Tiles take advantage of empty tiles: those tiles that have a bounding volume, but no content. Since a tile's content property does not need to be defined, empty non-leaf tiles can be used to accelerate non-uniform grids with hierarchical culling. This essentially creates a quadtree or octree without hierarchical levels of detail (HLOD).

Each tile's content.url property points to a tile that is one of the formats listed in the Status section above.

A tileset can contain any combination of tile formats. 3D Tiles may also support different formats in the same tile using a Composite tile.

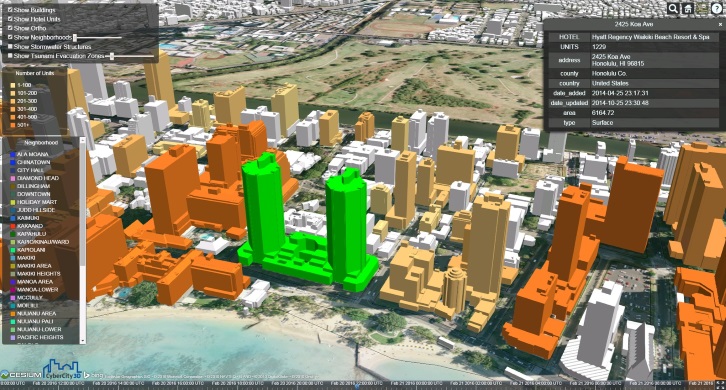

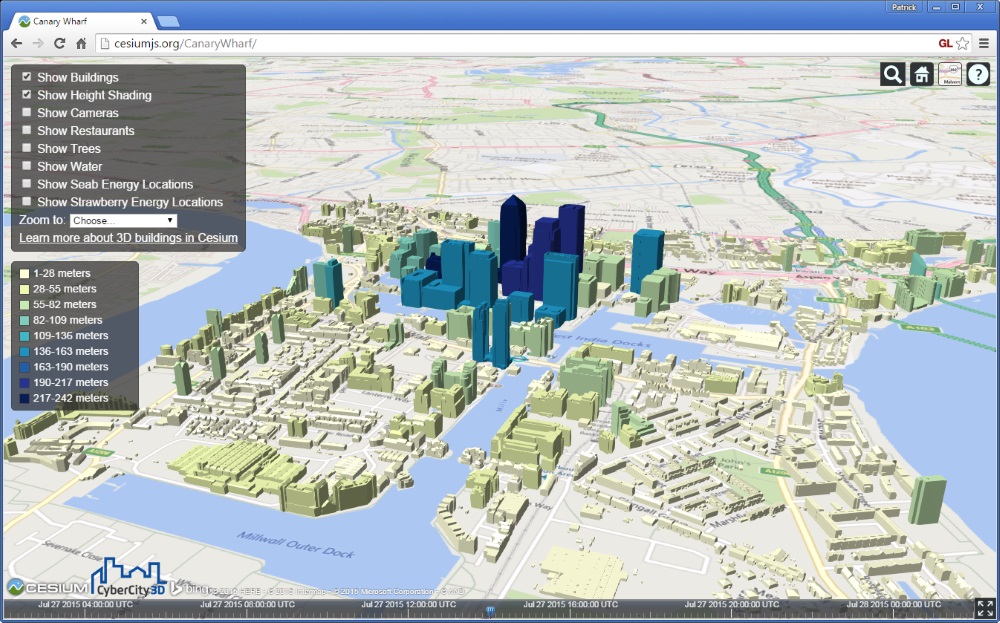

Buildings colored by height using declarative styling.

3D Tiles include concise declarative styling defined with JSON and expressions written in a small subset of JavaScript augmented for styling.

Styles generally define a feature's show and color (RGB and translucency) using an expression based on a feature's properties, for example:

{

"color" : "(${Temperature} > 90) ? color('red') : color('white')"

}This colors features with a temperature above 90 as red and the others as white.

For complete details, see the Declarative Styling spec.

- General Q&A

- Technical Q&A

- How do 3D Tiles support heterogeneous datasets?

- Will tileset.json be part of the final 3D Tiles spec?

- How do I request the tiles for Level

n? - Will 3D Tiles support horizon culling?

- Is screen-space error the only metric used to drive refinement?

- How are cracks between tiles with vector data handled?

- When using replacement refinement, can multiple children be combined into one request?

- How can additive refinement be optimized?

- What compressed texture formats do 3D Tiles use?

We expect the initial 3D Tiles spec to evolve until fall 2016. If you are OK with things changing, then yes, jump in. The Cesium implementation is in the 3d-tiles branch.

No, 3D Tiles are a general spec for streaming massive heterogeneous 3D geospatial datasets. The Cesium team started this initiative because we need an open format optimized for streaming 3D content to Cesium. AGI, the founder of Cesium, is also developing tools for creating 3D Tiles. We expect to see other visualization engines and conversion tools use 3D Tiles.

glTF, the runtime asset format for WebGL, is an open standard for 3D models from Khronos (the same group that does WebGL and COLLADA). Cesium uses glTF as its 3D model format, and the Cesium team contributes heavily to the glTF spec and open-source COLLADA2GLTF converter. We recommend using glTF in Cesium for individual assets, e.g., an aircraft, a character, or a 3D building.

We created 3D Tiles for streaming massive geospatial datasets where a single glTF model would be prohibitive. Given that glTF is optimized for rendering, that Cesium has a well-tested glTF loader, and that there are existing conversion tools for glTF, 3D Tiles use glTF for some tile formats such as b3dm (used for 3D buildings). We created a binary glTF extension (KHR_binary_glTF) in order to embed glTF into binary tiles and avoid base64-encoding or multiple file overhead.

Taking this approach allows us to improve Cesium, glTF, and 3D Tiles at the same time, e.g., when we add mesh compression to glTF, it benefits 3D models in Cesium, the glTF ecosystem, and 3D Tiles.

A common use case for 3D buildings is to stream a city dataset, color each building based on one or more properties (e.g., the building's height), and then hide a few buildings and replace them with high-resolution 3D buildings. With 3D Tiles, this type of editing can be done at runtime.

The general case runtime editing of geometry on a building, vector data, etc., and then efficiently saving those changes in a 3D Tile will be possible, but is not the initial focus. However, styling is much easier since it can be applied at runtime without modification to the 3D Tiles tree and is part of the initial work.

Yes, a quantized-mesh-like tile would fit well with 3D Tiles and allow Cesium to use the same streaming code (we say quantized-mesh-like because some of the metadata, e.g., for bounding volumes and horizon culling, may be organized differently or moved to tileset.json).

However, since Cesium already streams terrain well, we are not focused on this in the short-term.

Yes, there is an opportunity to provide an optimized base layer of terrain and imagery (similar to how a 3D model contains both geometry and textures). There is also the open research problem of how to tile imagery for 3D. In 2D, only one LOD (z layer) is used for a given view. In 3D, especially when looking towards the horizon, tiles from multiple LODs are adjacent to each other. How do we make the seams look good? This will likely require tool and runtime support.

As with terrain, since Cesium already streams imagery well, we are not focused on this in the short-term.

In many cases, yes. KML regions and network links are a clunky approach to streaming massive 3D geospatial datasets on the web. 3D Tiles are built for the web and optimized for streaming; true HLOD is used; polygons do not need to be triangulated; and so on.

Geospatial datasets are heterogeneous: 3D buildings are different from terrain, which is different from point clouds, which are different from vector data, and so on.

3D Tiles support heterogeneous data by allowing different tile formats in a tileset, e.g., a tileset may contain tiles for 3D buildings, tiles for instanced 3D trees, and tiles for point clouds, all using different tile formats.

3D Tiles also support heterogeneous datasets by concatenating different tile formats into one tile using the Composite tile format. In the example above, a tile may have a short header followed by the content for the 3D buildings, instanced 3D trees, and point clouds.

Supporting heterogeneous datasets with both inter-tile (different tile formats in the same tileset) and intra-tile (different tile formats in the same Composite tile) options allows conversion tools to make trade-offs between number of requests, optimal type-specific subdivision, and how visible/hidden layers are streamed.

Yes. There will always be a need to know metadata about the tileset and about tiles that are not yet loaded, e.g., so only visible tiles can be requested. However, when scaling to millions of tiles, a single tileset.json with metadata for the entire tree would be prohibitively large.

3D Tiles already support trees of trees. content.url can point to another tileset.json, which enables conversion tools to chunk up a tileset into any number of tileset.json files that reference each other.

There's a few other ways we may solve this:

- Moving subtree metadata to the tile payload instead of tileset.json. Each tile would have a header with, for example, the bounding volumes of each child, and perhaps grandchildren, and so on.

- Explicit tile layout like those of traditional tiling schemes (e.g., TMS's

z/y/x). The challenge is that this implicitly assumes a spatial subdivision, whereas 3D Tiles are general enough to support quadtrees, octrees, k-d trees, and so on. There is likely to be a balance where two or three explicit tiling schemes can cover common cases to complement the generic spatial data structures.

More generally, how do 3D Tiles support the use case for when the viewer is zoomed in very close to terrain, for example, and we do not want to load all the parent tiles toward the root of the tree; instead, we want to skip right to the high-resolution tiles needed for the current 3D view?

This 3D Tiles topic needs additional research, but the answer is basically the same as above: either the skeleton of the tree can be quickly traversed to find the desired tiles or an explicit layout scheme will be used for specific subdivisions.

Since horizon culling is useful for terrain, 3D Tiles will likely support the metadata needed for it. We haven't considered it yet since our initial work with 3D Tiles is for 3D buildings where horizon culling is not effective.

At runtime, a tile's geometricError is used to compute the Screen-Space Error (SSE) to drive refinement. We expect to expand this, for example, by using the Virtual Multiresolution Screen Space Error (VMSSE), which takes occlusion into account. This can be done at runtime without streaming additional tile metadata. Similarly, fog can also be used to tolerate increases to the SSE in the distance.

However, we do anticipate other metadata for driving refinement. SSE may not be appropriate for all datasets; for example, points of interest may be better served with on/off distances and a label collision factor computed at runtime. Note that the viewer's height above the ground is rarely a good metric for 3D since 3D supports arbitrary views.

See #15.

Unlike 2D, in 3D, we expect adjacent tiles to be from different LODs so, for example, in the distance, lower resolution tiles are used. Adjacent tiles from different LODs can lead to an artifact called cracking where there are gaps between tiles. For terrain, this is generally handled by dropping skirts slightly angled outward around each tile to fill the gap. For 3D buildings, this is handled by extending the tile boundary to fully include buildings on the edge; see above. For vector data, this is an open research problem that we need to solve. This could invole boundary-aware simplification or runtime stitching.

Often when using replacement refinement, a tile's children are not rendered until all children are downloaded (an exception, for example, is unstructured data such as point clouds, where clipping planes can be used to mask out parts of the parent tile where the children are loaded; naively using the same approach for terrain or an arbitrary 3D model results in cracking or other artifacts between the parent and child).

We may design 3D Tiles to support downloading all children in a single request by allowing tileset.json to point to a subset of a file for a tile's content similiar to glTF buffer and bufferView. HTTP/2 will also make the overhead of multiple requests less important.

See #9.

Compared to replacement refinement, additive refinement has a size advantage because it doesn't duplicate data in the original dataset. However, it has a disadvantage when there are expensive tiles to render near the root and the view is zoomed in close. In this case, for example, the entire root tile may be rendered, but perhaps only one feature or even no features are visible.

3D Tiles can optimize this by storing an optional spatial data structure in each tile. For example, a tile could contain a simple 2x2 grid, and if the tile's bounding volume is not completely inside the view frustum, each box in the grid is checked against the frustum, and only those inside or intersecting are rendered.

See #11.

3D Tiles will support the same texture compression that glTF will support. In addition, we need to consider how well GPU formats compress compared to, for example, jpeg. Some desktop game engines stream jpeg, then decompress and recompress to a GPU format in a thread. The CPU overhead for this approach may be too high for JavaScript and Web Workers.

The screenshots in this spec use awesome CyberCity3D buildings and the Bing Maps base layer.