In this repository, we demostrate using a simple convolution neural network (implented with Tensorflow) for variant calling. This is sepecially useful for DNA sequences with many insertion and deletion errors (e.g. from the single molecule DNA sequencing with PacBio's platform). With insertion and deletion errors, we will see more alignment slippage, even with SNP variants, there are some possibilities that the useful information is not precisely at the column of SNP location in the alignments. With a CNN, it is possible to aggregate information from nearby bases so it can outperform simple pile-up counting for variant calling. This is a simple test to see how well we can do it without signal level information. With the singal level information and a better alignment model, it is possible to further improve the performance.

VariantNet is a small neural network that makes variant calls from aggregated alignment information. Unlike DeepVariant (http://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/12/14/092890), we don't construct pile-up images and send the images to Google's DistBelief for computation. Instead, the alignments in a BAM file are converted to three 15 by 4 matrices for training the network and calling variants.

The first matrix simple encode the expected reference sequence using one-hot-like encoding. For a candidate variant site, we padded 7 bases both on the right and the left. The number of reads that aligned to a reference position is encoded in the first matrices. The 2nd matrix encode the difference of all the bases observed in the read-reference alignment before a reference location to the expected observations (= the first matrix). The 3rd matrix is similar to the 2nd matrix, expect none of the insertion bases in the reads are counted. (We will show an example below.)

The neural network used for training for calling variants contains two convolution/maxpool layer. We avoid operations that does not maintain the symmetry of the 4 different bases. For example, the max pool layers only appllyto different locations but not mix a subset of bases. And the convolution filters apply on 4 bases at the same time. After the two convolution layers, we add three full connected layers. The output layer contains two group of output. For the first 4 output unit, we like to learn about the possible bases of the site of interests. For example, if the data indicates the site has a base "C", we like to train the network to output [0, 1, 0, 0]. If a site has heterozygous variants, for example, "A/G", then we like to output [0.5, 0, 0.5, 0]. We use mean square loss for these 4 units. The 2nd group of output units contain variants type. We use a vector of 4 elements to encode possible scenarios. A variant call can be either "het"(heterozygous), "hom"(homozygous), "non-var" (non-variant), and "c-var" (complicated-variant). We use a softmax layer and use cross-entropy for the loss function for this 4 units.

We take a NA12878 PacBio read dataset generated by WUSTL (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov//bioproject/PRJNA323611) and align to GRCh38 with bwa mem. We train the NN using calling on a SNP call set generated by GIAB project (ftp://ftp-trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:/giab/ftp/release/NA12878_HG001/NISTv3.3.2/GRCh38, see also: https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/genome-in-a-bottle/s-t5vq8mBlQ). Like all short-read-based call set, there are a lot of region in the human genome that the short reads can not be aligned properly to call SNPs. We only training on those high confident regions. However, with PacBio read length and non-systematic random error, once we have trained a variant caller, we should be able to apply the caller for some more difficult regions to call SNPs more comprehensively in a genome.

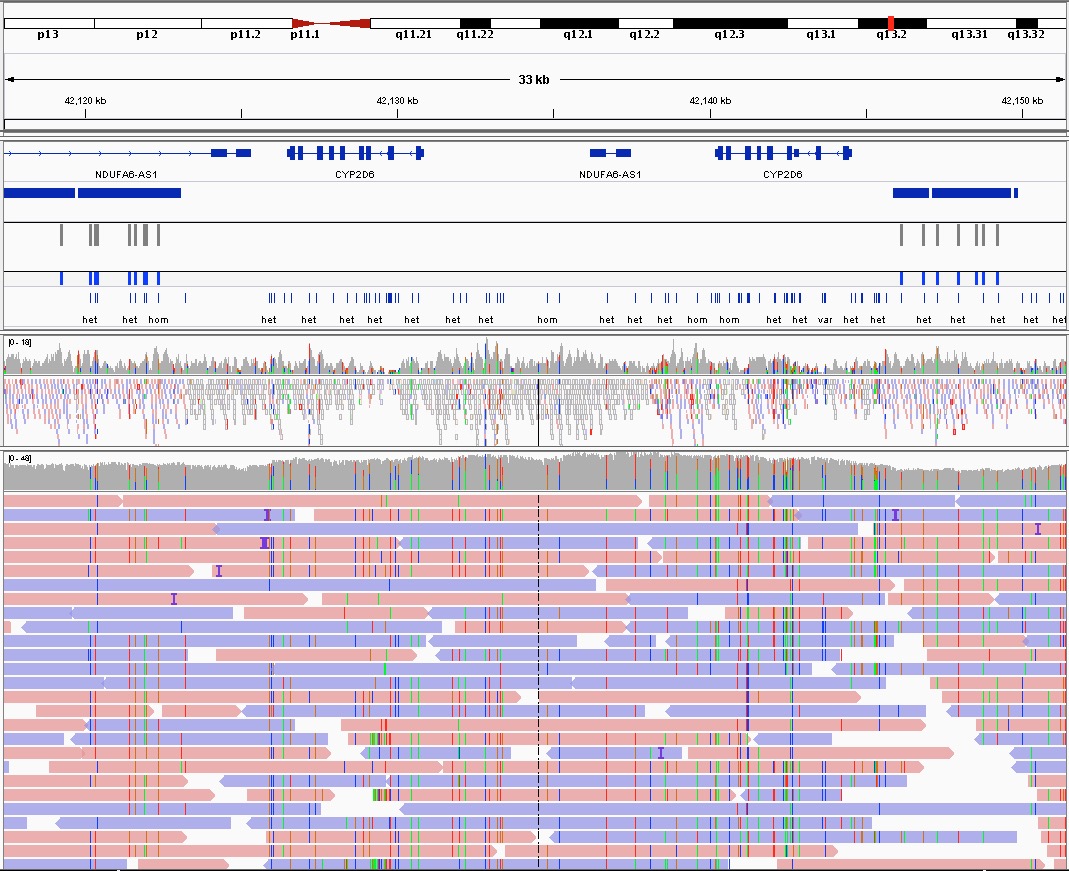

As a proof of principle, we only train using the calls on chromosome 21 and test on chromosome 22. The IGV screenshot below shows various VariantNet calls within the CYP2D6 region where there is no high confident variant calls from the GIAB project.

This simple work results from an exercise to get my feet wet learning neutral network beyond just knowing the theories. It also shows a simple neural network rather than a big one can already help for solving some simple but relative interesting problems in genomics.

I have not wrote an independent script to chain all machinary together. You can see an example in the Jupyter Notebook: https://github.com/pb-jchin/VariantNET/blob/master/jupyter_nb/demo.ipynb. The neural network model is defined in https://github.com/pb-jchin/VariantNET/blob/master/variantNet/vn.py.

July 13 2017

Jason Chin