A Theory of Type Polymorphism in Programming

Recap

- Introduction

- Illustrations of the Type Discipline

- A Simple Applicative Language and its Types

- The Semantic Soundness theorem

- A Well-Typing Algorithm and its Correctness

- Algorithm W

- The Syntactic Soundness theorem

- Algorithm J

- Types in Extended Languages

Section 3

Section 3 has subsections:

- The Language Exp

- Semantic Equations for Exp

- Discussion of Types

- Types and their Semantics

- Type Assignments

- Substitutions

- Well-Typed Expressions Do Not Go Wrong

Our purpose in this section is to prove the Semantic Soundness Theorem, which says that:

- If we can assign a type to an expression

- Then the runtime will never throw a type error at runtime

Two main things can go wrong with this.

- Runtime E, which throws type errors when it feels like it;

- Type system Z, where everything has type Zoidberg.

So we will have to firm up the statement of the theorem by

- stating what conditions the runtime can have for throwing a type error;

- strengthening the conditions for assigning a type to an expression.

3.1 The Language Exp (p.356)

- The AST for our language

- The objects our language can operate on (booleans, numbers, strings, functions, arrays, and so on)

- Booleans and functions are treated specially, as is W, the "Wrong" type.

- The environment type.

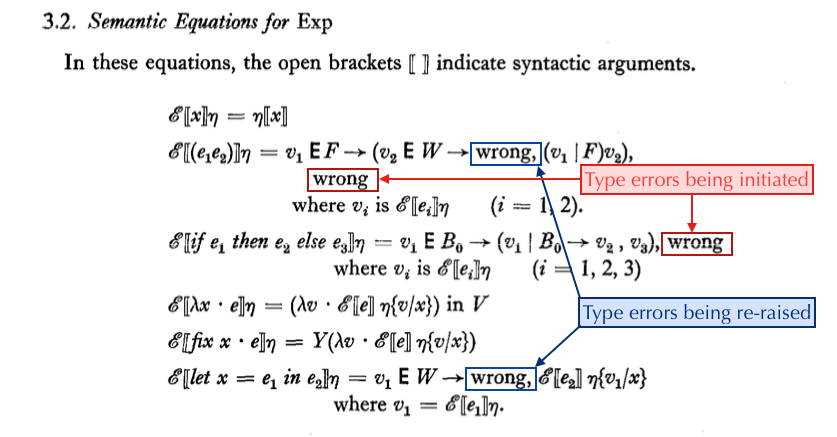

3.2 Semantic Equations for Exp (p.358)

- Defines the runtime evaluator for our language. This is a standard evaluator, but the important

parts are where it returns

wrong. These are the type errors:- If you call something, it has to be a Function

- The condition of an

if-then-elsemust be a Boolean.

- Three quick points:

fixis defined in terms of the Y combinator- Semantically,

let x = 3 in x+1is the same as(lambda (x) x+1)(3). But we agreed last week that as far as typing goes, we are going to treat them differently. - Our language is call-by-value, but call-by-name is very similar as far as evaluation is concerned, and more importantly, completely identical to the type checker.

3.3 Discussion of Types (p.359)

Values usually have types.

- Some values have one type, e.g.,

1has typeInt. - Some values have many types, e.g.,

lengthhas types[Int]->Intand[String]->Int - Some values have no type, e.g.,

if 3 then 4 else 5 - If a function has type

a -> b, and we give it value of typea, then we will get out a value of typeb, not an error.

We now have 2 goals:

- Prove that if we can assign a type to an expression and it is "well-typed" (which we will define in 3.5), the evaluator won't throw a type error at runtime. This is the remainder of section 3,

- Find a way to assign a type to an expression - this is section 4.

3.4 Types and their Semantics (p.359)

Syntax of types:

- Basic types

- Type variables

- Construction of function types from basic types and type variables

Semantics of monotypes: a value has a monotype if:

- It's a basic type, then the type of the value is the type of the object

- It's a function that always returns a type

bwhen given a typea, then it has typea->b- Another example of a function with no type: f(1) = "one", f(2) = 2, f undefined elsewhere

Semantics of polytypes

- <=

Notes on "downward closed" and "directed complete":

- These mostly come from Dana Scott's domain theory

- Directed Complete (aka "up complete" aka "DCPO") means that every directed subset has a supremum

- and in this case, it means that

3.5 Type Assignments (p.361)

This important section is where we define well-typed. The paper actually defines it twice, and the second definition (Proposition 3) is easier to work with.

3.6 Substitutions (p.363)

3.7 Well-Typed Expressions Do Not Go Wrong (p.364)

Types and Polymorphism chapter 3

Recap

- Introduction

- Illustrations of the Type Discipline

- A Simple Applicative Language and its Types

- The Semantic Soundness theorem

- A Well-Typing Algorithm and its Correctness

- Algorithm W

- The Syntactic Soundness theorem

- Algorithm J

- Types in Extended Languages

Section 3

Section 3 has subsections:

- The Language Exp

- Semantic Equations for Exp

- Discussion of Types

- Types and their Semantics

- Type Assignments

- Substitutions

- Well-Typed Expressions Do Not Go Wrong

Our purpose in this section is to prove the Semantic Soundness Theorem, which says that:

- If we can assign a type to an expression

- Then the runtime will never throw a type error at runtime

Two main things can go wrong with this.

- Runtime E, which throws type errors when it feels like it;

- Type system Z, where everything has type Zoidberg.

So we will have to firm up the statement of the theorem by

- stating what conditions the runtime can have for throwing a type error;

- strengthening the conditions for assigning a type to an expression.

3.1 The Language Exp (p.356)

- The AST for our language

- The objects our language can operate on (booleans, numbers, strings, functions, arrays, and so on)

- Booleans and functions are treated specially, as is W, the "Wrong" type.

- The environment type.

3.2 Semantic Equations for Exp (p.358)

- Defines the runtime evaluator for our language

- Three quick points:

fixis defined in terms of the Y combinator- Semantically,

let x = 3 in x+1is the same as(lambda (x) x+1)(3). But we agreed last week that as far as typing goes, we are going to treat them differently. - Our language is call-by-value, but call-by-name is very similar as far as evaluation is concerned, and more importantly, completely identical to the type checker.

3.3 Discussion of Types (p.359)

- Values usually have types.

- Some values have one type, e.g.,

1has typeInt. - Some values have many types, e.g.,

lengthhas types[Int]->Intand[String]->Int - Some values have no type, e.g.,

if 3 then 4 else 5 - If a function has type

a -> b, and we give it value of typea, then we will get out a value of typeb, not an error.

- Some values have one type, e.g.,

- We are going to define the concept "Well-typed"

- We now have 2 goals:

- Prove that if we can assign a type to an expression, it won't throw a type error at runtime. This is the remainder of section 3,

- Find a way to assign a type to an expression - this is section 4.

3.4 Types and their Semantics (p.359)

- Syntax of types

- Basic types

- Type variables

- Construction of function types from basic types and type variables

- Semantics of monotypes: a value has a monotype if:

- It's a basic type, then the type of the value is the type of the object

- It's a function that always returns a type

bwhen given a typea, then it has typea->b- Another example of a function with no type: f(1) = "one", f(2) = 2, f undefined elsewhere

- Semantics of polytypes