Accompanying material for "What to Know before Forecasting the Flu" paper.

Table of contents

- Surveillance Instability

- Between Surveillance Deviations

- Within Surveillance Deviations

- Drop off of surveillance

- Christmas Effect

- Data and Figures

Surveillance data is generally unstable. Usually it takes a number of updates from the agency before the surveillance data gets stabilized. This instability can vary from one country to another (within a single network) as well as between networks. Here we analyze the instability of two different kinds of surveillance networks:

- PAHO: FluNet network for ILI (a lab based system)

- CDC: ILINet network for ILI (an outpatient reporting system)

As can be seen both networks show surveillance instability.

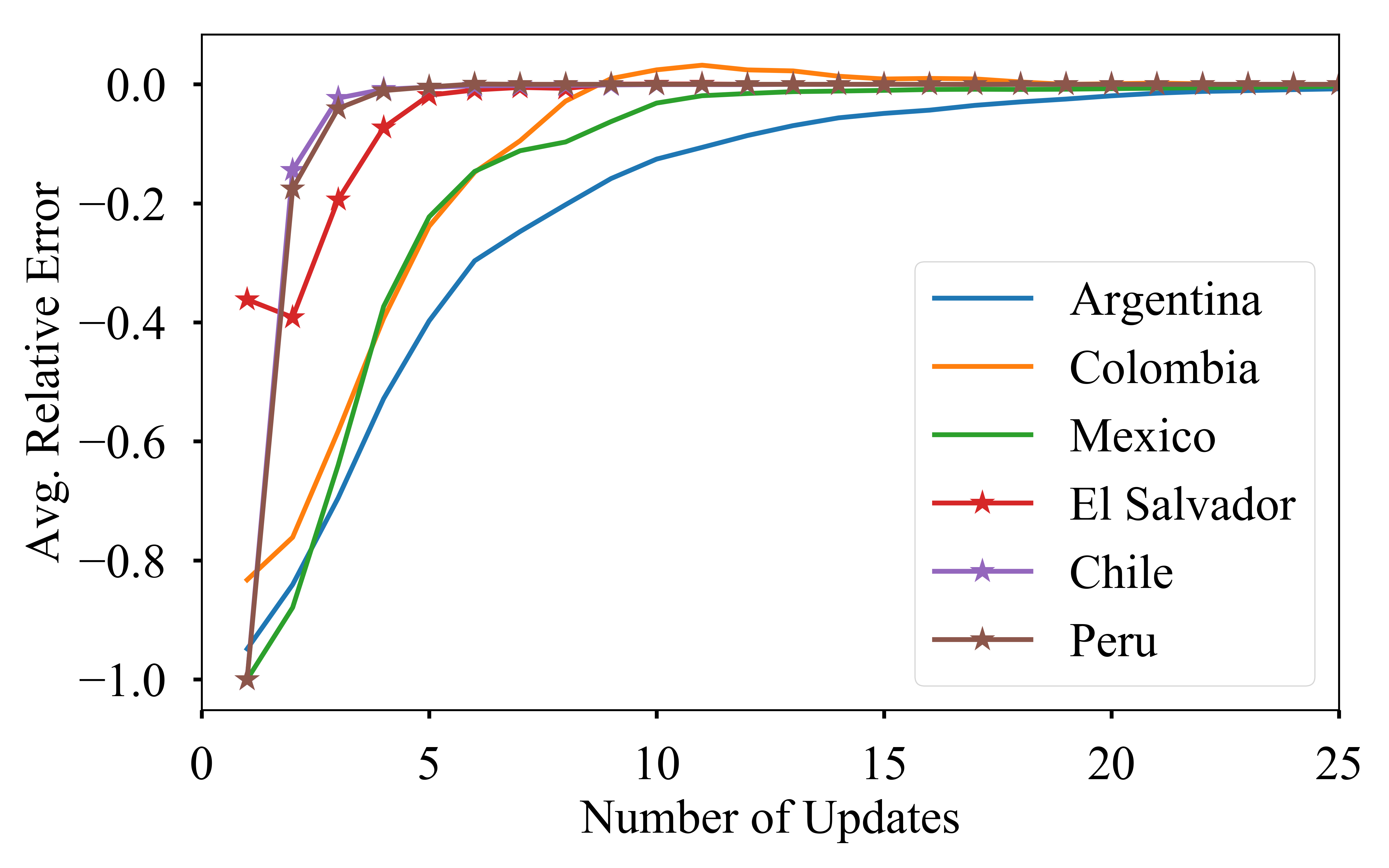

PAHO provides lab based surveillance feeds. We show the phenomenon of

surveillance drop-off on this network. PAHO updates for several Latin

American countries were collected daily from 2012-10 to 2013-10. ILI

estimates are generally updated at irregular intervals. We assumed the estimate

for a particular country for an epi week as available from the last update as

the true value and calculated percentage relative error as:

The snapshot of the daily downloads can be found in PAHO

updates. We can show the relative error as

a function of update as given below:

As can be seen in the figure countries fall nicely in two groups as slowly

stabilizing countries (such as Colombia and Peru) and quickly stabilizing

countries (such as Argentina and El Salvador).

CDC historical updates for national regions can be accessed from cdc archives (click on the link for an example). A snapshot of the dataset can be found in CDC historical archive snapshot

An animation of how the CDC updates happens for various epi weeks is shown

below. We animate the updates for 2013-2014 season for various reporting week

here:

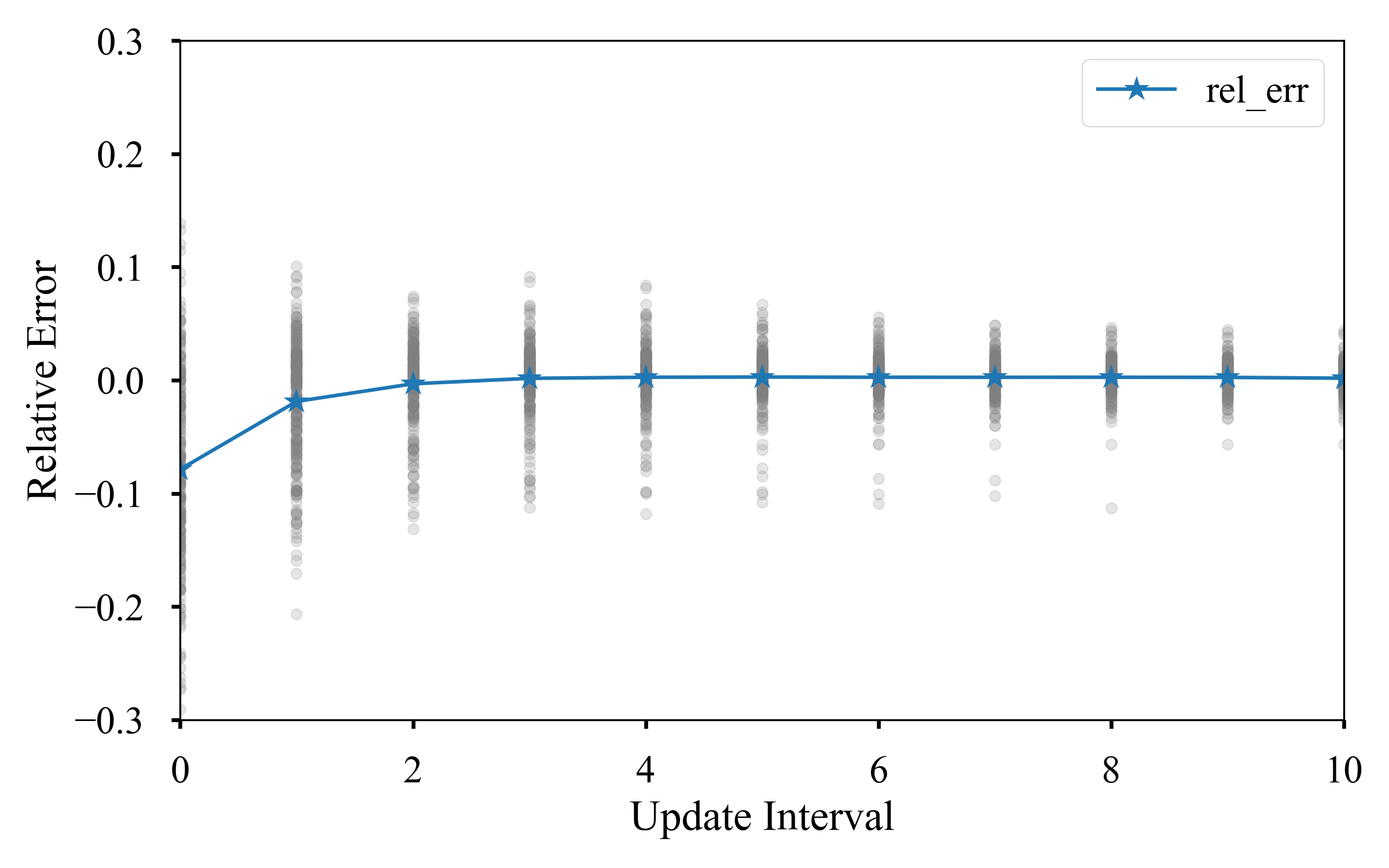

Similar to PAHO, we can plot the relative error of updates as a scatter plot as

shown below. We also plot the mean relative error in this figure.

As can be seen, similar to PAHO a number of updates is required before the

value stabilizes. However, CDC data for USA is found to be fast stabilizing.

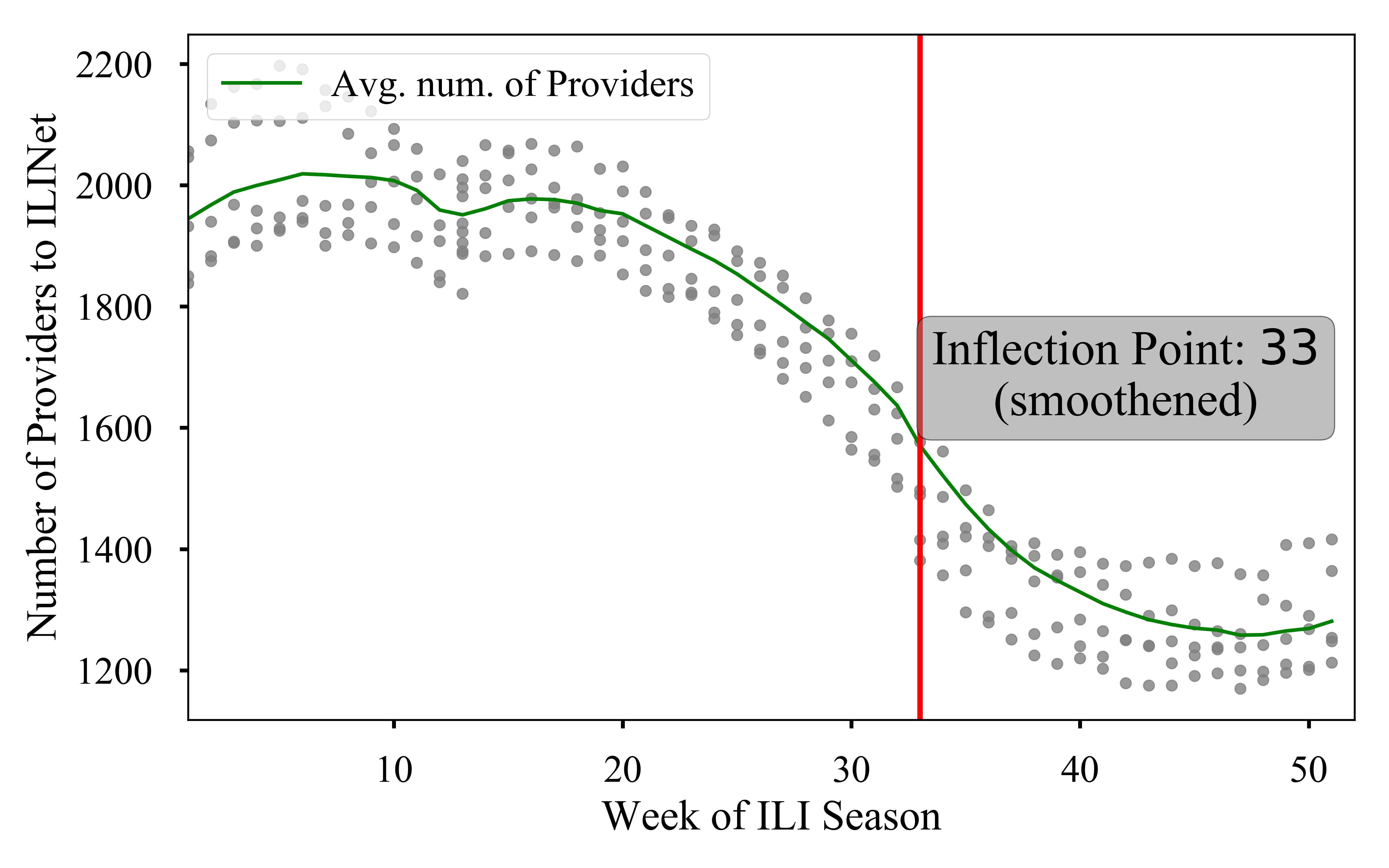

In our opinion piece we posited that, Post-peak the surveillance efforts drops.

We elucidate this by plotting the

scatter plot of the CDC ILINet reported number of providers as a function of

season week. As the scatter plot shows, the number of providers decreases

sharply at around season week

selected_cdc = cdc_data.query('season in [2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014]')

# Smoothing data

span_size = 4

avg_providers = selected_cdc.groupby('season_week').agg({'NUM. OF PROVIDERS': 'mean'})

smooth_providers = pd.ewma(avg_providers, span=span_size)

# Calculating gradients on smoothened data

provider_summary = pd.DataFrame(index=smooth_providers.index)

provider_summary['average'] = smooth_providers

provider_summary['grad2'] = np.gradient(np.gradient(smooth_providers.values.flatten()))

provider_summary['grad2sign'] = np.sign(provider_summary['grad2'])

# Calculating smoothened inflection point

provider_summary['inflect'] = pd.rolling_sum(provider_summary['grad2sign'],

window=span_size).shift(-span_size + 1)

# Inflection point = first point where you get a sum of span_size

inflection_point = provider_summary[provider_summary['inflect'] == span_size].index[0]The resultant scatter plot is shown below:

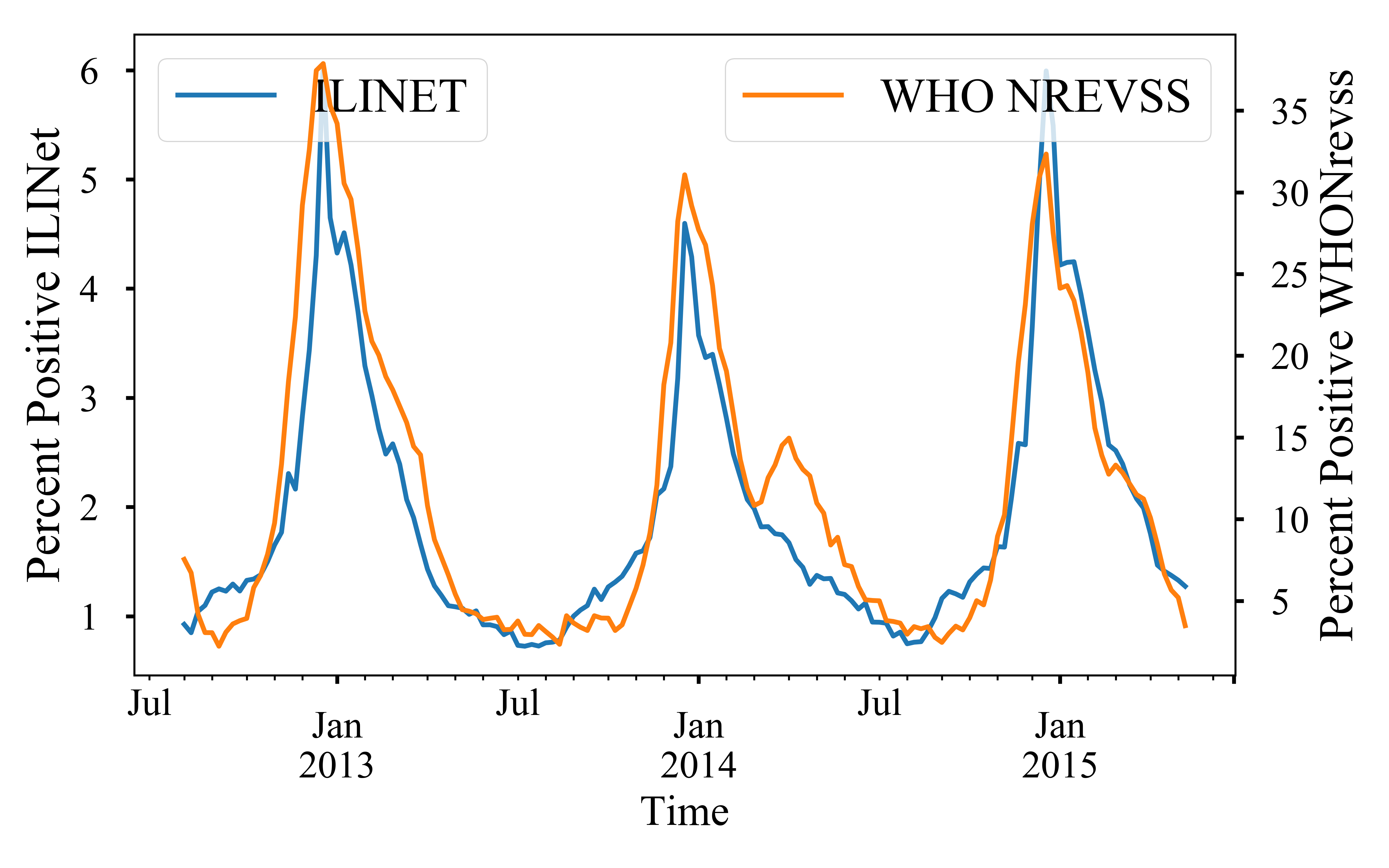

Often times, there are deviations in estimated ILI incidence for two different

networks for the same region. We illustrate this for CDC by comparing ILINet

against WHO NREVSS. We show this comparison for the national region. However,

similar analysis can be done for other regions as well. We compare the

estimates from two different networks below:

The data archive can be found in cdc

real time data snapshot

Similar to surveillance deviations, there could be deviations in ILI patterns for different strains that is broadly encompassed by the term ILI.

Strain estimates can be obtained from WHO NREVSS (which is a lab based

surveillance system). We scale the strain estimates to ILINet reported levels

and compare the incidence of total ILI vs Flu A and Flu B.

The code snippet for the scale conversions is given below:

# **************************************************************

# MANIPULATORS

# **************************************************************

# Get ratios

def get_ratios(X, col1='FLUA', col2='B', epsilon=1, suffix='_per'):

""" lambda funtion to get ratios of col1 and col2 as percentage.

"""

denom = X[col1] + X[col2] + epsilon

num1 = ((X[col1] + epsilon)/ denom).fillna(0)

num2 = ((X[col2] + epsilon)/ denom).fillna(0)

return pd.DataFrame({col1+suffix: num1,

col2+suffix: num2})

# Get ILINET values

def get_values(X):

""" lambda funtion to get ILINET VALUES

"""

return (np.round(X['FLUA_per'] * X['ILITOTAL']),

np.round(X['B_per'] * X['ILITOTAL']))

# ***************************************************************

# Scaling of WHO data to ILINet Scale

# ***************************************************************

combined_who_columns = [u'PERCENT POSITIVE', u'B',

u'FLUA', u'FLUA_per', u'B_per']

# calculating ratios of strains

cdc_who[['FLUA_per', 'B_per']] = (get_ratios(cdc_who, epsilon=0)

[['FLUA_per', 'B_per']])

# merging frames

combined_df = (cdc_net.join(cdc_who[combined_who_columns]))['2004':]

# Scaling ILINet according to strain ratios

combined_df['ILI_FLUA'], combined_df['ILI_FLUB'] = zip(*combined_df.apply(get_values, axis=1)) The raw ILINet data and NREVSS data is merged together to Combined data for public perusal.

This can be show pictorially as given below which shows a phase deviation

between Flu B and ILI

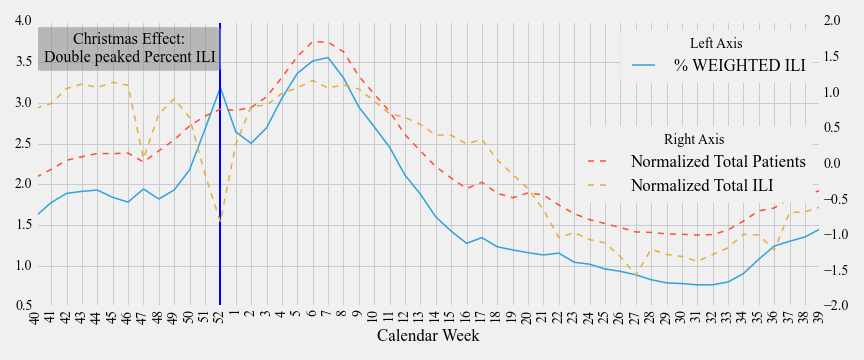

Surveillance measures can often suffer from variations such as holiday periods.

During holidays, such as Christmas in USA, people may chose to visit hospitals for only

essential visits (example: people may not visit for elective surgeries).

As a result, although the total number of patients may decrease, the number of

ILI related visits may remain the same. This contributes to an inflated

measure of Percent Weighted ILI which is used by CDC to determine the severity

of a flu season and lead to a double peaked season.

The code snippet for processing the data to verify the Christmass Effect is

given below:

def normalize(df):

return (df - df.mean(axis=0)) / df.std(axis=0)

used_cdc = cdc_data.query('2004 < season < 2015')

# Normalizing ILI and TOTAL to plot on same scale

cdc[['NormalizedILI', 'NormalizedTOTAL']] = (cdc[['ILITOTAL', 'TOTAL PATIENTS', 'season']].groupby('season')

.apply(normalize)[['ILITOTAL', 'TOTAL PATIENTS']])

metrics = ['NormalizedTOTAL', 'NormalizedILI', '% WEIGHTED ILI']

# Calculating means for each week

meanDF = used_cdc.groupby('WEEK').mean()[metrics]

# Reindexing the plotting dataframe to plot from 40-39 weeks

x=np.r_[np.arange(40, 53), np.arange(1,40)]

other_x = np.arange(len(x))

index_map = dict(zip(x, other_x))

plot_meanDF = meanDF.ix[x, :].reset_index()Christmass effect is highlighted below which shows that a dip in normalized

total visits coupled with a steady ILI related visit contributes to an inflated

percent ILI, historically around week 52 for ILINet in USA.