Writing tests, rules, managing them with loads of examples

- Unit tests: Make sure a class or a function or a unit of code works as expected in isolation

- Functional tests: Verify that the microservice does what it says from the consumer's point of view, and behaves correctly even on bad requests

- Integration tests: Verify how a microservice integrates with all its network dependencies

- Load tests: Measure the microservice performances

- End-to-end tests: Verify that the whole system works with an end-to-end test

- Write Tests First, Code Letter

- Add the reasonably amount of code you need to pass the tests

- You Shouldn't have more than one failing test

- Write code that passes the test and refactor it

- A test should fail the first time you run it. If it doesn’t, ask yourself why you are adding it.

- Never refactor w/o tests.

- If the test conditions are logical

AND- then go for multiple assertions. - if the conditions are logical -

OR- Multiple Test functions.

From the TDD point of view, if you don’t have a failing test there is no bug, so you have to come up with at least one test that exposes the issue you are trying to solve.

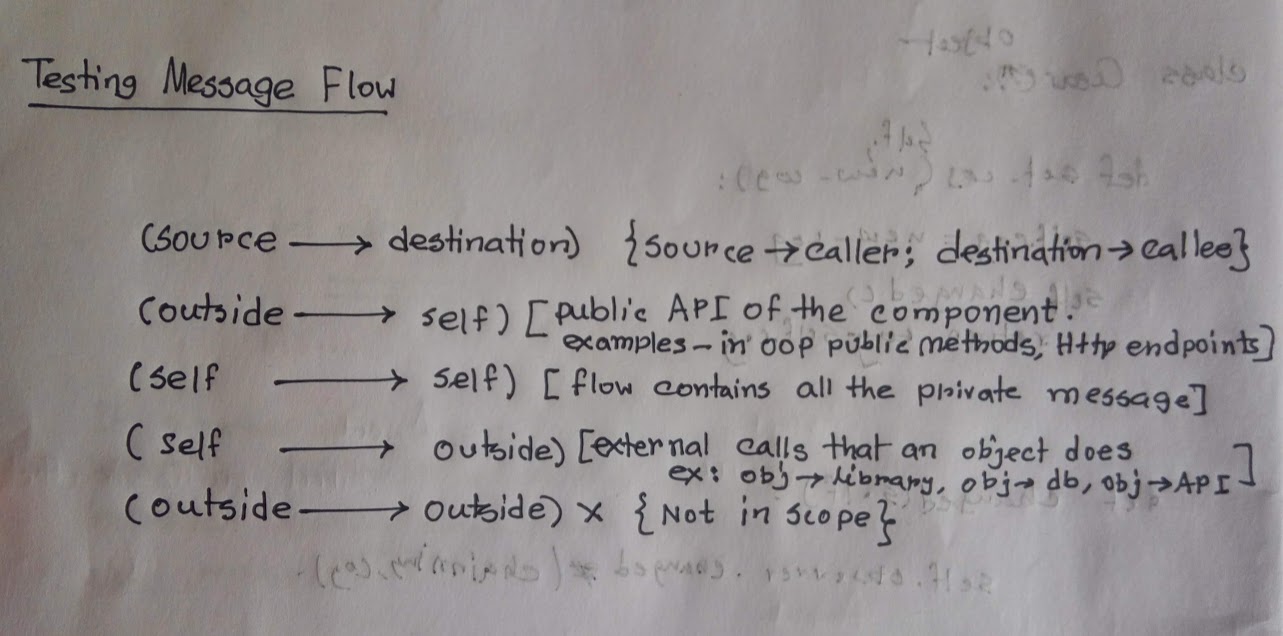

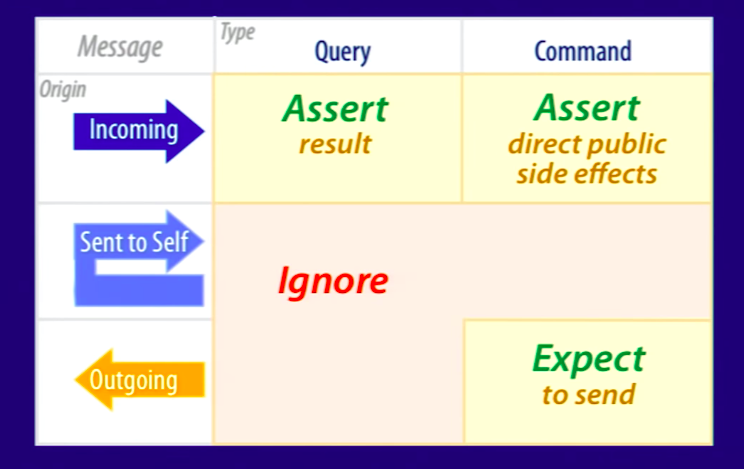

Testing should be based on the message flow between objects. For Example there are two types of messages -

- Query - Return Something / Change Nothing

- Command - Return Nothing / Change

And There are three ways message can flow between objects

- Incoming Messages - messages a method receives

- Self to Self Messages - calling to private method

- Outgoing Messages - messages a method return to another method

-

Incoming Query Message - test incoming query messages by making assertions about what they send back. Also test the interface not the implementation.

Now this following method should return the 2*input. For example if you give 2 it should return 4. It's a query message because whatever you send it does not change the state, rather it does some computation and return the value.

class Hello: def world(self, x): return x*2

To test it we should only need to assert the return value. We don't what it does inside from a TDD point of view.

def test_world(): assert Hello().world(2) == 4

-

Incoming Command Message - Assert about direct public side effects. For example - we might call a setter to set a value. By this way we are directly changing it's state. So we need to assert the changed state

class Hello: def set_world(self, x): self.world_name = x

def test_set_world(): h = Hello() h.set_world('earth') assert h.world_name == 'earth'

-

Self-to-self Query/Command Message - These are the conditions when a public method calls a private method. The Whole Application does not know about it. Only the public method are supposed to access it.

If the tested public method can access it and got the expected value it should, then no need to test it.

-

Outgoing Query Message - Say for example we are passing a value to another method. If it does not change the state we should not test it. Cause we are already testing

Incoming Query Message. -

Outgoing Command Message - they directly change the state of others by calling setters. There is a clear distinction between

Incoming CommandandOutgoing Command. For Example if we are testing thesettermethod than we call itIncoming Command, otherwiseOutgoing Commnad. Use aMock Objectto hide the implementation. Cause this is aunit testnot theintegration test.Mock Objects and their originals should play by common API.

>>> from unittest import mock

>>> m = mock.Mock()

>>> dir(m)

['assert_any_call', 'assert_called_once_with', 'assert_called_with', 'assert_has_cal\

ls', 'attach_mock', 'call_args', 'call_args_list', 'call_count', 'called', 'configur\

e_mock', 'method_calls', 'mock_add_spec', 'mock_calls', 'reset_mock', 'return_value'\

, 'side_effect']

>>> m.some_attribute

<Mock name='mock.some_attribute' id='140222043808432'>

>>> dir(m)

['assert_any_call', 'assert_called_once_with', 'assert_called_with', 'assert_has_cal\

ls', 'attach_mock', 'call_args', 'call_args_list', 'call_count', 'called', 'configur\

e_mock', 'method_calls', 'mock_add_spec', 'mock_calls', 'reset_mock', 'return_value'\

, 'side_effect', 'some_attribute']As you can see this class is somehow different from what you are used to. First of all, its instances do not raise an AttributeError when asked for a non-existent attribute, but they happily return another instance of Mock itself. Second, the attribute you tried to access has now been created inside the object and accessing it returns the same mock object as before.

Mock objects are callables, which means that they may act both as attributes and as methods. If you try to call the mock it just returns another mock with a name that includes parentheses to signal its callable nature

>>> m.some_attribute

<Mock name='mock.some_attribute' id='140222043808432'>

>>> m.some_attribute()

<Mock name='mock.some_attribute()' id='140247621475856'>>>> m.some_attribute.return_value = 42

>>> m.some_attribute()

42the mock returns is exactly the object that it is instructed to use as return value. If the return value is a callable such as a function, calling the mock will return the function itself and not the result of the function. Let me give you an example

>>> def print_answer():

... print("42")

...

>>>

>>> m.some_attribute.return_value = print_answer

>>> m.some_attribute()

<function print_answer at 0x7f8df1e3f400>The side_effect parameter of mock objects is a very powerful tool. It accepts three different flavours of objects: callables, iterables, and exceptions, and changes its behaviour accordingly.

-

If you pass an exception the mock will raise it

>>> m.some_attribute.side_effect = ValueError('A custom value error') >>> m.some_attribute() Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> File "/usr/lib/python3.6/unittest/mock.py", line 939, in __call__ return _mock_self._mock_call(*args, **kwargs) File "/usr/lib/python3.6/unittest/mock.py", line 995, in _mock_call raise effect ValueError: A custom value error

-

If you pass an iterable, such as for example a generator, a plain list, tuple, or similar objects, the mock will yield the values of that iterable, i.e. return every value contained in the iterable on subsequent calls of the mock.

>>> m.some_attribute.side_effect = range(3) >>> m.some_attribute() 0 >>> m.some_attribute() 1 >>> m.some_attribute() 2 >>> m.some_attribute() Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> File "/usr/lib/python3.6/unittest/mock.py", line 939, in __call__ return _mock_self._mock_call(*args, **kwargs) File "/usr/lib/python3.6/unittest/mock.py", line 998, in _mock_call result = next(effect) StopIteration

As this raises

StopIterationyou can safely use this mock object in a loop. -

if you feed side_effect a callable, the latter will be executed with the parameters passed when calling the attribute.

>>> def print_answer(): ... print("42") >>> m.some_attribute.side_effect = print_answer >>> m.some_attribute() 42

Slightly, More complex example with arguments

>>> def print_number(num): ... print("Number:", num) ... >>> m.some_attribute.side_effect = print_number >>> m.some_attribute(5) Number: 5

Side Effect can be given a class and return an instance of it.

>>> class Number:

... def __init__(self, value):

... self._value = value

... def print_value(self):

... print("Value:", self._value)

...

>>> m.some_attribute.side_effect = Number

>>> n = m.some_attribute(26)

>>> n

<__main__.Number object at 0x7f8df1aa4470>

>>> n.print_value()

Value: 26from unittest import mock

import my_obj_to_be_tested

def test_connect():

external_obj = mock.Mock()

my_obj_to_be_tested.MyObj(external_obj)

external_obj.connect.assert_called_with()Here we are testing connect method of MyObj. We are passing an external_obj to MyObj constructor. this external_obj can be anything like -

- database_object

- third-party-library

- saas API or anything

The Point is we don't know what external_obj does behind the scenes. All we know our MyObj should call external_obj's connect method. That's it. The rest is upto the service to do whatever it response, that's not headache for this scenario. Surely, that external_obj will make sure it sends response based on the documentation they provide. But it is their responsibility to test them, not MyObj's.

We expect MyObj to call the external_obj's connect method. So we express the expectation calling external_obj.connect.assert_called_with().

What happens behind the scenes? The MyObj class receives the fake external object and somewhere in its initialization process calls the connect method of the mock object. This call creates the method itself as a mock object. This new mock records the parameters used to call it and the subsequent call to its assert_called_with method checks that the method was called and that no parameters were passed.

In this case an object like -

class MyObj():

def __init__(self, repo):

repo.connect()would pass the test, as the object passed as repo is a mock that does nothing but record the calls. As you can see, the __init__() method actually calls repo.connect() , and repo is expected to be a full-featured external object that provides connect in its API. Calling repo.connect() when repo is a mock object, instead, silently creates the method (as another mock object) and records that the method has been called once without arguments.

The assert_called_with method allows us to also check the parameters we passed when calling.

To show this let us pretend that we expect the MyObj.setup method to call setup(cache=True, max_connections=256) on the external object. Remember that this is an outgoing command, so we are interested in checking the parameters and not the result.

The new test can be something like -

def test_setup():

external_obj = mock.Mock()

obj = myobj.MyObj(external_obj)

obj.setup()

external_obj.setup.assert_called_with(cache=True, max_connections=256)In this case an object that passes the test can be -

class MyObj():

def **init**(self, repo):

self._repo = repo

repo.connect()

def setup(self):

self._repo.setup(cache=True, max_connections=256)If we change the setup method to -

def setup(self):

self._repo.setup(cache=True)the test will fail with the following error

E AssertionError: Expected call: setup(cache=True, max_connections=256)

E Actual call: setup(cache=True)Patching, in a testing framework, means to replace a globally reachable object with a mock, thus achieving the goal of having the code run unmodified, while part of it has been hot swapped, that is, replaced at run time.

It means to inform Python that during the execution of a specific portion of the code you want a globally accessible module/object replaced by a mock. A Small Usecase -

our function given a file_path - get_info(file_path) returns a tuple like the following

(

'file_name',

'../../relative-file-name',

'/home/alamin/absolute-file-path' # <- Here ??? we don't know the output in advance

# so we need to patch it.

)from unittest.mock import patch

def test_get_info():

filename = 'somefile.ext'

original_path = '../{}'.format(filename)

with patch('os.path.abspath') as abspath_mock:

test_abspath = 'some/abs/path'

abspath_mock.return_value = test_abspath

fi = FileInfo(original_path)

assert fi.get_info() == (filename, original_path, test_abspath)We can patch also using a decorator

@patch('os.path.abspath')

def test_get_info(abspath_mock):

test_abspath = 'some/abs/path'

abspath_mock.return_value = test_abspath

filename = 'somefile.ext'

original_path = '../{}'.format(filename)

fi = FileInfo(original_path)

assert fi.get_info() == (filename, original_path, test_abspath)Multiple patches

@patch('os.path.getsize')

@patch('os.path.abspath')

def test_get_info(abspath_mock, getsize_mock):

filename = 'somefile.ext'

original_path = '../{}'.format(filename)

test_abspath = 'some/abs/path'

abspath_mock.return_value = test_abspath

test_size = 1234

getsize_mock.return_value = test_size

fi = FileInfo(original_path)

assert fi.get_info() == (filename, original_path, test_abspath, test_size)Please note that, the decorator which is nearest to the function is applied first. Always remember that the decorator syntax with @ is a shortcut to replace the function with the output of the decorator, so two decorators result in

@decorator1

@decorator2

def myfunction():

passwhich is a shortcut for

def myfunction():

pass

myfunction = decorator1(decorator2(myfunction))Patching immutable objects

The objects (classes, modules, functions, etc.) that are implemented in C are shared between interpreters59, and this requires those objects to be immutable, so that you cannot alter them at runtime from a single interpreter.

An example of this immutability can be given easily using a Python console -

>>> a = 1

>>> a.conjugate = 5

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'int' object attribute 'conjugate' is read-onlyWhat has this immutability to do with patching? What patch does is actually to temporarily replace an attribute of an object (method of a class, class of a module, etc.), which also means that if we try to replace an attribute in an immutable object the patching action will fail.

let's say we have a file - file_logger.py

import datetime

class Logger:

def __init__(self):

self.messages = []

def log(self, message):

self.messages.append((datetime.datetime.now(), message))and the tests for it

from unittest.mock import patch

from fileinfo.logger import Logger

@patch('datetime.datetime.now')

def test_log(mock_now):

test_now = 123

test_message = 'A test message'

mock_now.return_value = test_now

test_logger = Logger()

test_logger.log(test_message)

assert test_logger.messages == [

(test_now, test_message)

]Now when we run pytest -svv it throws error:

TypeError("can't set attributes of built-in/extension type 'datetime.datetime'")Solution - importing or subclassing an immutable object gives you a mutable “copy” of that object.

@patch('fileinfo.logger.datetime.datetime')

def test_log(mock_datetime):

test_now = 123

test_message = "A test message"

mock_datetime.now.return_value = test_now

test_logger = Logger()

test_logger.log(test_message)

assert test_logger.messages = (test_now, test_message)- when you have to create more than 3 mocks, there must be something wrong in the testing approach

- consider the complexity of the mocks

- The third advice is to consider mocks as “hooks” that you throw at the external system, and that break its hull to reach its internal structure. These hooks are obviously against the assumption that we can interact with a system knowing only its external behaviour, or its API. As such, you should keep in mind that each mock you create is a step back from this perfect assumption, thus “breaking the spell” of the decoupled interaction. Doing this you will quickly become annoyed when you have to create too many mocks, and this will contribute in keeping you aware of what you are doing (or overdoing).

- pytest - The testing framework used for python

Please read CONTRIBUTING.md for details on our code of conduct, and the process for submitting pull requests to us.

We use SemVer for versioning. For the versions available, see the tags on this repository.

- Alamin Mahamud - Initial work - alamin-mahamud

See also the list of contributors who participated in this project.

This project is licensed under the MIT License - see the LICENSE.md file for details

- Hat tip to anyone whose code was used

- Inspiration

- etc