- Introduction

- How to start

- Cases of study

- Pertussis Model

- Model Generation

- Sensitivity analysis

- Model Calibration

- Model Analysis

- References

In this document we describe how to use the R library epimod. In details, epimod implements a new general modeling framework to study epidemiological systems, whose novelties and strengths are:

- the use of a graphical formalism to simplify the model creation phase;

- the automatic generation of the deterministic and stochastic process underlying the system under study;

- the implementation of an R package providing a friendly interface to access the analysis techniques implemented in the framework;

- a high level of portability and reproducibility granted by the containerization (Veiga Leprevost et al. 2017) of all analysis techniques implemented in the framework;

- a well-defined schema and related infrastructure to allow users to easily integrate their own analysis workflow in the framework.

The effectiveness of this framework is showed through two case studies, the wellknown and simple SIR model, and much more complex model related to the pertussis epidemiology in Italy.

Install epimod:

install.packages("devtools")

library(devtools)

install_github("qBioTurin/epimod", dependencies=TRUE)

library(epimod)

Then, the following function must be used to download all the docker images used by epimod:

downloadContainers()

All the epimod functions print the following information:

- Docker ID, that is the CONTAINER ID which is executed by the functon;

- Docker exit status, if 0 then the execution completed with success, otherwise an error log file is saved in the working directory.

We now describe how the framework functions can be combined to obtain an analysis workflow for the Pertussis model introduced in the main paper: A computational framework for modeling andstudying pertussis epidemiology and vaccination.

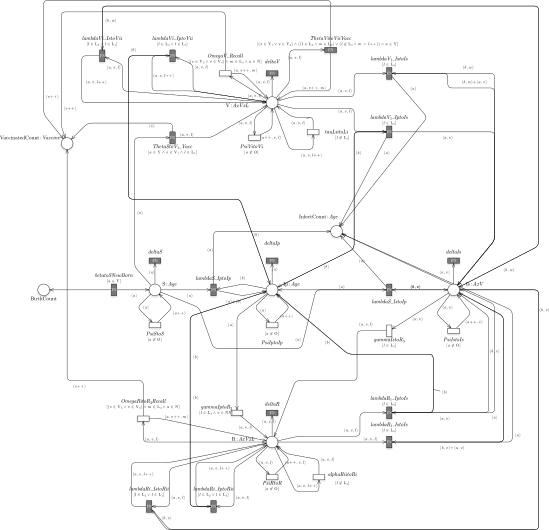

Petri Net representation of the Pertussis model.

We first introduce all the functions, the constants, and the numerical values associated with the general transitions rate (the black boxes in figure ). Then, we show the proposed framework and how it can be successfully used to study and analyze pertussis infection and the relative vaccination cycle in Italy. All the details regarding the function associated to the general transition and the parameters exploited in the simulations are reported in the ReadMe.pdf into the folder pdf.

The starting point is the derivation from the Pertussis model the corresponding underlying stochastic and deterministic processes by using the function model_generation. Then the derived deterministic process is represented by a system of 179 ODEs, while the derived stochastic process is characterized by 1965 possible events. Let us observe that the functions associated with the general transitions (the black boxes in figure ) are implemented in the file transitions.cpp, which is passed as input parameter of the function.

generation <- model_generation(net_fname = "./Net/Pertussis.PNPRO",

functions_fname = "./Cpp/transitions.cpp")

Since the model is characterized by 15 unknown parameters, three of the represent the probabilities of having (i) the susceptible infection success, i.e., the infection of a susceptible individual due to a contact with an infected individual, namely prob_infectionS, (ii) the resistant infection success, i.e., the infection of a vaccinated or recovered individual with the minimum resistance level due to a contact with an infected individual, namely prob_infectionR_l1, and finally (iii) the natural boosts, i.e., the restoring of the resistance level to the maximum when a person with resistance level different from the minimum level comes into contact with an infected individual, namely prob_boost. The remaining 12 unknown parameters are the initial marking of the susceptible and recovered places. We can apply the function sensitivity_analysis() on the deterministic process previously generated and considering the data of the period from 1974 to 1994 as reference targets, in order to identify which parameters are most sensitive w.r.t. the counts of infects. Therefore, the following function input parameters are passed:

- solver_fname: Pertussis.solver;

- n_config: the model is run 2^14;

- f_time: since all the rates were calculated daily and we want to simulate 21 years, then the f_time has to be 365*21;

- s_time: the step time is set to 1 year, 365 days;

- parameters_fname: in Functions_list.csv the parameters which have to vary and also the parameters that have to be passed to the general functions stored in transition.cpp are reported.

#> Tag Name Function

#> 1 g b_rates b_rate

#> 2 g c_rates c_rate

#> 3 g d_rates d_rate

#> 4 g v_rates v_rate

#> 5 g probabilities probability

#> 6 i init initial_marking

#> Parameter1

#> 1 file='/home/docker/data/input/init_conf.RData'

#> 2 file='/home/docker/data/input/init_conf.RData'

#> 3 file='/home/docker/data/input/init_conf.RData'

#> 4 file='/home/docker/data/input/init_conf.RData'

#> 5 file='/home/docker/data/input/init_conf.RData'

#> 6 file='/home/docker/data/input/init_conf.RData'

- functions_fname: in Functions.R the functions reported in the third column of Functions_list.csv are implemented. For instance, the function associated to the generation of the three probabilities is defined as follows:

# if x is null then it means that we have to sample the values by

# exploiting the uniform distribution between 0 and 0.25. Let us note

# that three values corresponding to the three probabilities are

# generated since the uniform intervals are all identical to [0,0.25].

# Differtly when x is not null, then it means the we are using the

# optimization algorithm and the prob. values are already sampled,

# for this reason we take just the first three values of x (the vector

# with size equals to the number of parameter which are varing),

# 0 is given to the probability of vaccination failure that will be used

# in model_analyis.

# The three values obtained are automatically saved in a file called as

# the corresponding name in the Function_list.csv (second column),

# and then read and exploited by the functions in transitions.cpp .

probability <- function(file, x = NULL)

{

load(file)

if( is.null(x) ){

x <- runif(n = length(probabilities), min=0, max=0.25)

x[length(x)] = 0

}

else{

x <- c(x[c(1:3)],0)

}

return(matrix(x, ncol = 1))

}

Let us note that the probabilities values generated are used by the functions modeling all the transitions representing the contact between two individuals (implemented in transitions.cpp). For this reason the tag associated with this parameter is g and not p (where p has to be used when a transition rate or a single place is under analysis). Similarly, the function initial_marking characterizing the generation of the unknown initial markings of certain places is defined in order to satisfy the following constraints: Hence, the values estimated during the sensitivity analysis and model calibration steps are the proportions of the total number in each age class. For instance, the values .4 and .8 might be associated to S_a1 and R_a1_n**v_l4, meaning that the 0.3333333% (i.e., .4/(.4+.8) ) of the total 866703 individuals are in S_a1 and the remaining are in R_a1_nv_l4. For more details regarding the constraints in eqs. and the functions associated to the general transitions (in specific how the probabilities are used), see Sec. General transitions, eq. . 7. target_value_fname: since we are interested to calculate the PRCCs over the time w.r.t. the count of infects per year, the Select.R file provides the function to obtain the vector storing the total number of infections per year.

Select<-function(output)

{

ynames <- names(output)

col_names <- "(InfectCount_a){1}[0-9]{1}"

col_idxs <- c( which(ynames %in% grep(col_names, ynames, value=T)) )

# Reshape the vector to a row vector

ret <- rowSums(output[,col_idxs])

return(as.data.frame(ret))

}

- reference_data: the Pertussis surveillance data from the 1974;

#> 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980

#> Infects 7413 10786 18354 8076 12582 18142 14170

- distance_measure_fname: the squared error estimator via trajectory matching on the number of cases per year is implemented through the msqd() function.

msqd<-function(reference, output)

{

ynames <- names(output)

# InfectCount is the place that counts how many new infects occurs during the whole

# period, for this reason we have to do the difference to obtain the number of cases

# per year. Given this difference the squared error is calculated w.r.t. the reference

# data.

col_names <- "(InfectCount_a){1}[0-9]{1}"

col_idxs <- c( which(ynames %in% grep(col_names, ynames, value=T)) )

infects <- rowSums(output[,col_idxs])

infects <- infects[-1]

diff<-c(infects[1],diff(infects,differences = 1))

ret <- sum(( diff - reference )^2 )

return(ret)

}

Finally,

sensitivity_analysis(n_config = 2^14,

parameters_fname = "./input/Functions_list.csv",

functions_fname = "./Rfunction/Functions.R",

solver_fname = "./Net/Pertussis.solver",

f_time = 365*21,

s_time = 365,

timeout = "1d",

parallel_processors=40,

reference_data ="./input/reference_data.csv",

distance_measure_fname="./Rfunction/msqd.R",

target_value_fname="./Rfunction/Select.R"

)

PRCCs values for the selected input parameters with respect the number of infections.

From figure it is straightforward to argue that the prob_infectionS is the most important parameter affecting the infects behavior, followed by prob_infectionR_l1. Differently the prob_boost probability and the initial number of susceptible and recovered individuals in each age class are irrelevant with respect to the infection behavior.

Scatter Plot showing the squared error between the real and simulated infection cases.

In figure , the squared error between the real and simulated infection cases from 1974 to 1994 are plotted varying the prob_infectionS parameter (on the x-axis) and prob_infectionR_l1 parameter (on the y-axis). Each point is then colored according to a linear gradient function starting from color dark blue (i.e., lower value) and moving to color light blue (i.e., higher values). From this plot we can observe that higher squared errors are obtained when prob_infectionS assumes values greater than 0.09 (see light blue) or smaller than 0.06 (see the dark blue points, representing the parameters configuration with minimum error w.r.t. the real data, when prob_infectionS values are between [0; 0.1]). Therefore, according to this we shrunk the search space associated with the prob_infectionS parameter from [0; 0.25] to [0; 0.1] in the calibration phase.

The aim of this phase is to adjust the model unknown parameters to have the best fit of simulated behaviors to the real data, i.e. the reference data. Firstly, the function model_calibration() is applied on the generated deterministic process to fit its behavior to the real infection data (from 1974 to 1994) using squared error estimator via trajectory matching implemented in the function msqd() passed as an input parameter. Note that the information derived by the sensitivity analysis is exploited to reduce, where it is possible, the number of parameters to be estimated and/or their search space.

model_calibration(parameters_fname = "./input/Functions_list.csv",

functions_fname = "./Rfunction/Functions.R",

solver_fname = "./Net/Pertussis.solver",

f_time = 365*21,

s_time = 365,

reference_data = "./input/reference_data.csv",

distance_measure_fname = "./Rfunction/msqd.R",

# Vectors to control the optimization

# init_V taken from trace id 13521

ini_v = c(0.05, 0.07, 0.1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0),

ub_v = c(0.25, 0.1, 0.25, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1),

lb_v = c(0, 0, 0, 1e-7, 1e-7, 1e-7, 1e-7, 1e-7, 1e-7, 1e-7,

1e-7, 1e-7, 1e-7, 1e-7, 1e-7),

ini_vector_mod = TRUE

)

#> Optimal configuration:

#> prob_boost prob_infectionS prob_infectionR_l1 init_S_a1 init_S_a2

#> 87160 0.09328468 0.06742504 0.09999983 0.3362519 0.04485452

#> init_S_a3 init_R_a1_nv_l4 init_R_a2_nv_l1 init_R_a2_nv_l2 init_R_a2_nv_l3

#> 87160 0.968471 0.3454245 0.02239408 0.01690299 1e-07

#> init_R_a2_nv_l4 init_R_a3_nv_l1 init_R_a3_nv_l2 init_R_a3_nv_l3

#> 87160 0.9765406 0.3134586 0.06156321 0.0007210937

#> init_R_a3_nv_l4

#> 87160 0.0001294989

Model Calibration considering the deterministic model. Here a subset of the trajectories obtained from the optimization phase. The color of each trajectory depends on the squared error w.r.t. the Pertussis surveillance trend (red line). The black line is the optimal one.

Then, starting from the parameters configuration obtained from the deterministic model calibration, that is

0.0932847, 0.067425, 0.0999998, 0.3362519, 0.0448545, 0.968471, 0.3454245, 0.0223941, 0.016903, 10^{-7}, 0.9765406, 0.3134586, 0.0615632, 7.210937\times 10^{-4}, 1.294989\times 10^{-4}

the function model_calibration() is applied on the generated stochastic process to fit its behavior to the real infection data using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) via trajectory matching, implemented in the R script aic.R. Let us note that the parameter search space of this second optimization step is computed from the result obtained from the previous step considering a 20% confidence interval around each parameter value.

model_calibration(parameters_fname = "./input/Functions_list.csv",

functions_fname = "./Rfunction/Functions.R",

solver_fname = "./Net/Pertussis.solver",

solver_type = "TAUG",

f_time = 365*21,

s_time = 365,

n_run = 250,

parallel_processors=40,

reference_data = "./input/reference_data.csv",

distance_measure_fname = "./Rfunction/aic.R",

ini_v = best_run,

ub_v = 1.2*best_run,

lb_v = .8*best_run,

ini_vector_mod = TRUE

)

#> [1] "Optimal configuration="

#> prob_boost prob_infectionS prob_infectionR_l1 init_S_a1 init_S_a2

#> 726 0.1028314 0.06422971 0.1173022 0.3996977 0.04611963

#> init_S_a3 init_R_a1_nv_l4 init_R_a2_nv_l1 init_R_a2_nv_l2 init_R_a2_nv_l3

#> 726 1.082384 0.2943042 0.02526472 0.01475493 8.009888e-08

#> init_R_a2_nv_l4 init_R_a3_nv_l1 init_R_a3_nv_l2 init_R_a3_nv_l3

#> 726 0.9688963 0.3208456 0.06788778 0.000676801

#> init_R_a3_nv_l4

#> 726 0.0001424256

a) 25000 trajectories (grey) over the whole time interval are reported. b) Boxplots considering the best configuration.

Figure shows trajectories (grey lines) for the 15 best parameters configurations discovered. The blue area contains the average trajectories derived for the first ten best parameter configurations, while the two green lines provide the associated confidence interval. We can observe that a good approximation of the surveillance data (red line) from the 1974 to 1994 is obtained.

In this last phase of our workflow the user can analyse the calibrated model to answer specific questions and to derive new insights. In our case study we show a simple what-if analysis. In particular we investigate the impact of different vaccination failure probabilities with respect to the number of infection cases. The simulated time period is from 1974 to 2016, and the pertussis vaccination program is started in 1995, with an average vaccination coverage starts from 50% and transitions linearly to 95% in 8 years, (“Ministero Della Salute. Coperture Vaccinali.” n.d., @Tozzi2014).

In details, the model_analysis() function is applied by exploiting the optimal parameters configuration derived from the calibration analysis on the stochastic model, namely optim.stoch.

model_analysis(solver_fname = "./Net/Pertussis.solver",

f_time = 365*43,

s_time = 365,

n_config = 1,

n_run = 250,

parallel_processors = 40,

solver_type = "TAUG",

parameters_fname = "./input/Functions_list.csv",

functions_fname = "./input/Functions.R",

ini_v = optim.stoch ,

ini_vector_mod = TRUE)

250 trajectories (grey) considering the stochastic model. The blue dashed line is the mean trend and the red one the Pertussis surveillance.

Probability of vaccine failure settled to .1.

Probability of vaccine failure settled to .2.

Fig. shows the decreasing of number of infection cases after the starting of the vaccination policy, with dynamics comparable with the reference data. If we add to the model a vaccination failure probability, i.e. we add a fourth probability given by pv (see Sec.General transitions, eq. ), then we have to modify the vector returned by the function probability() implemented in Functions.R as follows:

probability <- function(file, x = NULL)

{

load(file)

if( is.null(x) ){

x <- runif(n = length(probabilities), min=0, max=0.25)

x[length(x)] = 0

}

else{

##### Here we add the vaccination failure probability: p_v

x <- c(x[c(1:3)],p_v)

}

return(matrix(x, ncol = 1))

}

In figures and we show how the number of infection cases is affected by the increasing vaccination failure probabilities from 0.1 to 0.20. We can observe that only probabilities greater than 0.10 have an effect on the number of infection cases.

Figures , , and show a) 250 trajectories (grey) considering the stochastic model over the whole time interval. The blue dashed line represents the mean trend; the red line represents the Pertussis surveillance trend. In the picture b) the boxplots over the time period are plotted, and in c) the zoom considering the last 21 years is reported.

Gonfiantini, M V, E Carloni, F Gesualdo, E Pandolfi, E Agricola, E Rizzuto, S Iannazzo, M L Ciofi Degli Atti, A Villani, and A E Tozzi. 2014. “Epidemiology of Pertussis in Italy: Disease Trends over the Last Century.” Eurosurveillance 19 (40).

“Ministero Della Salute. Coperture Vaccinali.” n.d.

Veiga Leprevost, Felipe da, Björn A Grüning, Saulo Alves Aflitos, Hannes L Röst, Julian Uszkoreit, Harald Barsnes, Marc Vaudel, et al. 2017. “BioContainers: an open-source and community-driven framework for software standardization.” Bioinformatics 33 (16): 2580–2.