- How to Make the Most of Your Computer Science/Data Science/Statistics Major

- What no one else will tell you. :-)

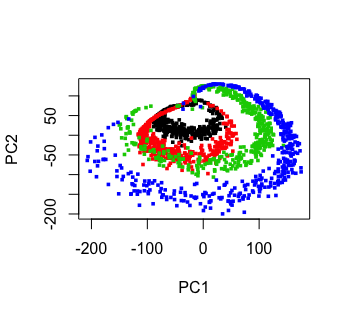

- The picture above

- What do CS/DS/Stat graduates do?

- General coursework/learning issues

- Windows vs. Mac vs. Linux

- Coursework is not enough

- The impact of grade inflation

- Textbooks

- "No pain, no gain"

- Avoid taking many courses in your major on a P/NP grading basis

- Don't do a double major

- Make real USE of what you learn

- Get a summer internship

- Speaking and writing skills, and evolution of your career over time

- Don't neglect the social aspect

- Possibly engage in undergraduate research

- Seeking and interviewing for jobs

- Beware of hype

- Graduate school

- Specific courses

Computer Science, Data Science and Statistics (CS/DS/Stat) are fascinating, fast-growing fields. It's an exciting time to be in tech -- but how to make the most of this opportunity?

The organization of this document is as follows.

-

Approximately the first half will be on general learning issues, e.g. careful reading of textbooks, what to do about grade inflation, the importance of summer internships etc.

-

The second half will provide advice on studying specific courses, such as machine learning.

We'll cover a variety topics, so let's get started!

Different people may have different views on the topics here. Thus we must begin with my explaining the background affecting my views/biases.

^ My PhD, done back in ancient times, was in pure, very abstract math. Later, I shifted to statistics and CS, and I am a founder of both the CS and Stat Departments at my university. My current research areas are machine learning, fairness in data analysis, and missing values.

^ I've been fortunate to be recognized for my work. I've won the university-wide Distinguished Teaching Award, Outstanding Adviser Award, and Distinguished Public Service Award. My book, Statistical Regression and Classification: from Linear Models to Machine Learning was the 2017 recipient of the Ziegal Award, given by the statistics journal Technometrics.

^ I am quite active in the R programming language. I've published a number of books that use R, and have written various packages on CRAN and GitHub. I've served as Editor-in-Chief of the R Journal and Associate Editor of the Journal of Statistical Software. I've written a rather popular R tutorial, and a criticism of the R tidyverse that many have found cogent.

^ My time in industry was long, long ago, but I have always kept close ties to the real world. I frequently interact with people in Silicon Valley, and keep close tabs on the job market. Syndicated columnist Joyce Lain Kennedy has featured my advice on career issues in her books, Resumes for Dummies, Job Hunting for Dummies and Cover Letters for Dummies.

Of course, the material here represents my own views only, and does not imply endorsement by my university or department. And again, others may have different opinions.

This was generated by the R prVis R package, written by my research students Tiffany Jiang, Robert Tucker, Robin Yancey, and Wenxuan (Allen) Zhao. Robin was a grad student at the time, but all the rest were undergraduates. The work was presented at useR! 2019 in Toulouse, France, by Allen.

-

Many in CS--and in fact many from DS, Stat and virtually any tech field--become software engineers.

-

Data scientists: Analyzing, graphing and predicting data. Wide variation here, in terms of job responsibilities, possible need for an advanced degree and so on. If for instance the job title involves "machine learning," an advanced degree is almost certainly required.

-

Database analysts: A big bank would quickly go out of business if its software and hardware couldn't keep up with the huge daily olume of checks, credit card transaction and so on. Making the database speedy is thus of huge importance.

-

Security specialists: How to foil the Bad Guys? This requires a finely intricate knowledge of computer systems, especially computer networks.

Note that most software engineers are young, say below age 35. There is considerable age discrimination in all tech fields, but much more so in this particular one. Data scientists and security specialists may stay in those fields much longer, but in any case, be prepared for your career to evolve over time.

Windows is a great OS for non-tech people. But most CS/DS/Stat people and their employers use some form of Unix, either on a Mac or on Linux. Use your Unix system for all of your daily computer work -- not just coding, but also e-mail, essay writing, Website building and so on---in order to really learn it well.

And don't neglect the command line! Facility in the Unix bash shell is especially useful. Develop skill in this.

If you want to retain Windows for video games or whatever, that's fine -- set up your system to dual-boot the two systems. In fact, the setting up of this will itself be a valuable learning experience. Don't use the Linux subsystem in Windows. It lacks many capabilities.

THIS IS AN EXTREMELY IMPORTANT POINT.

Sadly, typical courses won't give you the true, practical insight you need to effectively do CS/DS/Stat work. Examples:

-

As noted below, it's good to understand OS, e.g. in terms of how a machine boots up. Yet this almost certainly will not be covered in an OS class, let alone in computational courses in DS/Stat.

-

In a DS/Stat course, you will learn about stat methods that assume a normal/Gaussian distribution. But you almost certainly won't be taught that no such assumptions hold in real life (e.g. no one is 100 feet tall or has a negative height), or whether the assumptions matter.

The remedy: Learn nonpassively. Question what you learn. Fill in the gaps, first by trying to reason them out, then by consulting with your instructors, then finally--of course--by going to the Internet.

These days, many instructors not only give absurdly high grades--at my university, I've seen a number of courses in which 1/3 of the students get A+ grades!--but also are very undemanding. Their lectures lack depth, and avoid the more difficult concepts. Exams are simply warmed-over homework problems.

You should seek out the professors who will challenge you, but if you get some easy ones, don't fool yourself into thinking that that A/A+ grade means you have good knowledge of the subject matter. Again, go further than what is expected of you, as explained above.

Beware of any stat/ML instructor who presents matters with a flow chart ("in this situation, do this..."). It will typically be a misleading oversimplification.

Most professors choose their textbooks very carefully, but naively and wrongly assume the students actually read them.

Read the textbook! Read it for deep understanding. If you see a page consisting only of prose, with no code, no equations, and no figures, do not conclude there is no content! On the contrary, that page may be one of the most important ones in the book. You actually should spend extra time on such pages.

Pause often for thought. Your reading will likely cause you to have lots of questions. Indeed, if you have no questions, you probably have not been reading critically. Think hard in trying to answer the questions yourself, and ask your professor or TAs about the rest, resorting to the Internet if that doesn't work.

What does this old saying mean, in the CS/DS/Stat context? It does NOT mean "Work yourself to death." It does NOT mean "Take 5 courses per semester/quarter," and so on. On the contrary, the more courses you take in a given term, the less you will learn; your learning will be too shallow.

What it does mean is to give your work long, hard thought. Can't see how to even get started on your programming assignment? Don't immediately seek your TA!!!! Think more and more on it. Let it percolate in your mind. Go for a long walk to mull it over. This is where you become a good programmer. If you don't go through this, you likely never do well in a coding interview, let alone the job.

It also follows that if the problem statement for your assignment gives you a detailed outline of the code structure, the instructor is not doing you a favor. Try to take courses from professors who challenge you.

The same point holds for mathematical courses, whether in a CS, Math or Stat Department.

Frankly, this looks bad to a potential employer or graduate admissions committee. It suggests, usually accurately, that the student put in only minimal work in those P/NP courses. It even has the connotation that the student is "gaming the system."

Ever hear the old saying, "Jack of all trades, but a master of none"? Look, many employers are NOT going to be impressed with your breadth; job interviewes will probe your depth.

In writing your own code, make sure to use a debugging tool. You may have learned to do this in your intro programming course, but then just forgot it after the course ended. Big mistake! The reason your course taught you how to use the debugger is to BENEFIT YOU! Once you get good at the debugger, it will really shorten the time you need to find and fix your code bugs. Do you really want to pull an all-nighter to fix your bugs? No? Then use a debugging tool.

Story: Once there were two students talking to the instructor across the hall from my office. I heard one say to the other in awe, "Did you hear about Mary? She finished the programming assignment quickly, added some comments, and turned it in after 45 minutes!" What's wrong with this picture? Mary added the comments to her code only because she knew she'd be docked points without them. Totally wrongheaded! Again, the purpose of the comments is to BENEFIT YOU!

Write some comments even before you start coding at the start of each code file, stating what the code in that file will do; it will really help organize your thoughts. Similarly, write comments before each function, to say what it is doing, what its arguments are, etc. Again, write these BEFORE you code the function itself. Then within the function, if a group of, say, 3-4 lines perform some mini-task, precede them with a comment, saying something like "In the next 3 lines, we determine which array elements caused the total to exceed its limit."

Comments become indispensable when you return to some code after a few months, and zero recall of what you did.

Means, proportions and graphs in your daily life, especially Simpson's Paradox:

This applies particularly to DS/Stat majors, but it is definitely relevant to CS students as well.

Data analysis shows up on a daily basis, on vitally important topics such as the economy and the Covid pandemic. The value of such data can range from enormously informative to enormously misleading. Since you are data experts!, you'll want to hone your skills at ferreting out the good and the bad.

When viewing any data on proportions, the key question is "What's the denominator?" For instance, when viewing a statement like, "The infection rate for Covid is x%," ask, "x% out of which subpopulation?" x% of all people? Of all adults? Of people who are exposed to a sufferer of Covid?" and so on. This makes a huge difference.

You can't call yourself a data expert unless you know--and can cogently explain--Simpson's Paradox. The Wikipedia entry is good, and it contains a really famous example involving UC Berkeley graduate admissions. (The R language has the data on this, in a dataset named UCBAdmissions.) But I like reading a paper cleverly titled Good for Women, Good for Men, Bad for People_ That title says it all! Do yourself an epic favor by doing some slow, careful reading here, and keep it in mind forever. Yes, it IS that important.

And here is a good Covid example.

It generally is not easy to get these, but they are highly worth the effort. They get you out of the student mental ruts like "Can I get partial credit?" and "Will this be on the final exam?"

You're not in school here. You're part of a team. If you're writing code, make sure it is valuable to the employer. Make doubly sure that your code WORKS, including on edge cases, and that the code is clear (see the points above about comments).

Be punctual (even if your permanent-position co-workers are not). Don't be shy about speaking up in meetings. Make sure to ask questions about what you don't understand (though first make your best effort to figure out the answers on your own).

Your employer hired you in part because they may want to hire you after you graduate, so this is really like a very extended interview. Keep this in mind, but on the other hand, don't let this fact pressure you. You are there to learn, and hopefully to enjoy. A post-graduation job offer would be nice, no question about it, but treat that as a bonus.

I know, you're saying, "Yes, yes, we've been told about this ever since high school." But it's even more of a key issue for CS/DS/Stat people.

Craig Barrett, former CEO of Intel, once famously remarked, "The half-life of an engineer is only a few years." In other words, if say you begin your career as a software engineer, you will likely find that after 5-10 years, you are asked to transition into management or some other "talking job." Or, if you look for a job at another employer, you may find that the main type of work open to you is of a "talking job" nature.

Though there are of course exceptions, the odds are that the further along you are in your career, the less time you spend doing explicitly technical things, and the more time you spend talking and writing. If you've ever visited a company that produces software, you probably noticed that most of the coders are in their 20s or early 30s; this is no coincidence.

And though, yes, coursework in writing and speaking helps to some extent, you can only grow by working on these things yourself.

-

When you are writing something, continually ask yourself what you can do to make your thoughts clearer. And, make sure that you put down your draft once in a while and do something else; when you return, you may be horrified at what you've written :-) and make improvements. Repeat the cycle.

-

If you have a fear of speaking out in the group, overcome it! All the coursework in the world won't solve this; it needs to come from YOU. And don't obsess over an "error" that you may feel you made in speaking up. Even the smartest, most respected people often make erroneous or inappropriate things.

-

If you did not grow up speaking English, don't worry about your accent or grammar. Just work on expressing yourself well. Engage in campus club or volunteer activities where you can really grow verbally.

Success in the real world stems perhaps 20% from technical ability and 80% skill in interpersonal relations. Don't be a hermit. Join the CS Club. Volunteer to help out in your department's or your university's annual Open House. Know what's going on in the outside world. Read something other than science fiction or fantasy. Think carefully about the societal implications of technology.

If done well, assisting a professor with her research can have huge salutatory effects. But this is only the case if the work is nontrivial, with the student being encouraged to engage in independent, creative analysis. The student typically has up to then done only narrow, highly structured, "sanitized" work in his courses. So, research work, in which student plays a role in not only solving a problem but also defining it in the first place, can have a transformative impact on the student.

On the other hand, if the student is just assigned to do straightforword coding, say, then the value of research is essentially nil.

Job hunting (including for internships) can be a full-time job in its own right. Your campus employment center will help (including via the job fairs they sponsor on campus), and you can scan the Web. Use your social network too!

You should maintain a GitHub repo containing code for your more important projects. It's best that they be independent projects, i.e. not for a class, but the latter type is useful too. This is your portfolio, just as an artist or architect has a portfolio of his/her artwork. It's possible that you may be asked about these projects in interviews. Be prepared to answer design-oriented questions. Why did you set up your data structures in a certain way? What if the goal of the code had been slightly different? What would you have to change?

If the code is for data analysis, why did you choose this approach? What statistical assumptions did you make?

When you have an interview (first on the phone or Zoom, later on-site), prepare by researchng the nature of the employer. Practice mock interviews with friends. Did you get an A in your Programming Language course or Statistical Regression Analysis or whatever? Great, but can you talk about it cogently? If the job involves coding, again, practice with friends! Give each other little coding tasks, which you try to code on a whiteboard in front of them.

By the way, during the real interview, don't worry if you don't answer everything perfectly, e.g. could not fully complete a coding task. The interviewers want to see how you think. After the interview, don't obsess on errors that you made, either in code or answers to qualitative questions.

And no matter how introverted you are, don't just sit there "like a bump on a log"! Speak up! Venture opinions! Ask questions!

You will often hear people rave about some new tech "innovation" (I'll call it INV), say a new programming language or library, or a new machine learning method. There may well be considerable merit to the New, New Thing, but much of the hoopla will typically be hype. Ask yourself:

-

How "new" is INV, really? Most innovations are incremental.

-

Is INV's "science fiction"-like name, say "Radical Random Trek," more marketing than technical advance?

-

If the advocates of INV supply data showing INV superior, how broad was their empirical investigation? Does their analysis set up a "straw man" for comparison?

-

Is INV fulfilling a genuine need, as opposed to one created to justify using INV?

-

Do the people who are raving about INV seem to not really understand INV, just jumping on the bandwagon?

This is not to say INV is not a genuine advance. But a dose of healthy skepticism may be in order.

"Should I go to grad school?" This is one of the most common questions I get from students.

To answer, I tell them an old joke: A man is walking on a dock and passes a huge yacht. He asks the owner how much the yacht costs. The owner answers, "If you have to ask, then you can't afford it." The point is that, for the most part, you will only gain from grad school if you really want to do it; if you have to ask whether to pursue graduate study, then you "can't afford it," in terms of time and money spent etc. This is true both for a Master's degree and a PhD.

Master's degree quality varies tremendously from school to school. If you get a CS/DS/Stat Bachelor's degree from a research-oriented university, and later get a Master's from a non-research school, you may find that the latter's Master's curriculum is similar to, maybe even inferior to, your undergrad material.

Similarly, many elite universities now offer Master's programs that, frankly, have as their sole purpose making money for the school. They can be spotted this via these characteristics:

-

Truly exhorbitant tuition.

-

Low admissions bars; students who had no hope of being accepted to the university now get in easily.

-

Their Web sites promoting the program put inordinate emphasis on how many employers hire the program's graduates.

On the other hand, one should not necessarily talk about whether the graduate program at University X is "good." It depends on the research area. X may be very good in, say, computer security but weak in machine learning. So take your field(s) of interest into account.

In applying to grad school, note that letters of recommendation tend to be crucial, even more than grades and test scores. See advice and sample letters, as well as here.

Once you get to grad school, you'll notice immediately that the climate has changed from the undergrad world. Your classmates will now consist of people who have a genuine intellectual curiosity about CS, which may not have been the case for many of your undergrad friends. In class, you are now expected to be much more active, questioning and independent-thinking.

Machine learning (ML) is NOT a branch of software engineering. Your ML course will almost certainly have you do some coding, but if you conclude that ML is about choosing which function to call, and knowing the function arguments, you've missed the point very badly.

ML is also not about plugging into formulas. It is an art, not a science. There is no formulaic solution to problems, especially overfitting. Professor Yaser Abu-Mostafa of Caltech, a prominent ML figure, once summed it up

The ability to avoid overfitting is what separates professionals from amateurs in ML.

So you can see that ML is not about what specific function to call or what formula to plug into. It really is an art, not a science. My Google query on "overfitting" yielded 6,560,000 results! Again, careful thought about the subject matter is key.

Absolutely central to ML in particular and predictive modeling in general is the distinction between conditional and unconditional probability, especially the conditional mean. Again, keep the intuition in mind throughout your study of ML.

See above material on ML courses. If all you know--or all your instructor requires you to know--is how to use various R packages, you are pretty much useless to employers.

Calculus

Again, don't just plug into formulas; gaining intuition is key.

Example: Say we want to find a local minimum of a function f. We set f' = 0, then check whether f'' > 0. Fine, but WHY? Why does f'' > 0 tell us we are at a minimum?

Linear algebra

Again, intuition is crucial, e.g. the geometric interpretation of vector spaces. Again, the WHY is important, e.g. why are matrices useful? Could we do the same operations without them?

Abstract math

At most universities, CS majors are required to take a course in Discrete Math, and I recommend it for DS/Stat as well. But, although the specific content is important, the real value is that abstract math enhances your analytical powers. It is much easier to understand databases on a practical level, for instance, if you have good powers of abstraction.

The following anecdate will be instructive, I believe. Once a PhD student in math came to me for help, saying, "I have some code to write but don't see how to do it." I knew he was quite bright, so I said, "Say no more. Just use recursion." He'd had only a single course in programming, so he said, "What's recursion?" I told him to look up the Towers of Hanoi problem. He came back the next day, saying, "I wrote the whole thing in 5 lines!"

Most CS students struggle with recursion. (DS/Stat students: R and Python also allow recursion.) How was this math student able to use it effectively after seeing just one example? The answer is that he knew mathematical induction, and recursion is just the flip side of induction.

Note though that I said that math student knew induction, meaning that he understood WHY it is a valid method of proof. Do you?

If you do any kind of work with computers, the deeper your knowledge of computer systems, the better. Some examples:

-

I was recently using an R package that at one point gave me an error message, "Non-numeric data encountered." It seemed odd, because the variable in question was numeric, wage income in dollars. R is written in the C language (as is Python), which distinguishes between integers like 3 and real numbers such as 8.1, so I immediately realized and solved the problem.

-

R and Python are interpreted languages. In some cases, this can make them run slowly. (Do you know why? And why are vectorized operations faster? Click here.) With Big Data, execution speed may be imperative, and the solution may be to write code that is mainly R/Python but also partly C/C++. Again, skill in the latter is important.

-

Illustrative story, especially for CS students but for all: Once the daughter of family friends of ours received a scholarship to study the Chinese language in China. (She was not Asian, by the way.) She returned home with lots of pictures on her laptop. Unfortunately, her little sister dropped the machine, and it would not reboot. The pictures were lost! But with my knowledge of OS--boot up, file systems and so on--I was able to recover most of the pics.

-

Large software applications, e.g. the bank database example above, generally place a premium on speed. This in turn requires a firm understanding of high level hardware and low-level software.

-

One way to possibly speed up your code is to use parallel computation, on a multicore machine, on a computing cluster, and even a GPU. The R ecosystem includes a number of packages for this, such as parallel, foreach and future. BUT BEWARE! Your parallel code may actually be slower than your serial (i.e. nonparallel) version. To use parallelism effectively requires a good knowledge of things like how memory access works. You can click here to learn more.

-

Computer security requires a keen knowledge of operating systems, especially network operation. For a great read and a glimpse into how hackers exploit holes in the OS, read The Cuckoo's Nest, by Cliff Stoll. There's also a bit at the very beginning of the film A Social Network, the story of the founding of Facebook.

If you are required to take a course in assembly language, do NOT treat this as "just another language." It is your window into computer systems, a way to learn about computer structure and OS..

By the time you graduate, you who are in CS, and ideally those of you in DS/Stat, should be able to answer questions like (these are just examples):

-

How does an OS boot up?

-

How can a computer have several processes going at once? (And are there really running simultaneously?)

-

How does a file system work?

Most or all of these matters will NOT be covered in typical OS and computer architecture classes. You should have enough curiosity to think about them and track down the answers if you can't figure them out yourself.

CS majors:

-

Computer networks: The basis for most computer applications today

-

Database: The "information" in "Information Technology"

-

Computer security: If your school doesn't offer one, suggest that they do

DS/Stat majors:

-

Time series analysis

-

Stochastic processes

-

Sampling theory/experimental design

-

Discrete math

-

C/C++

-

Computer systems (bits, bytes, CPU, memory, us etc.)

-

The above CS courses, especially database

Everyone:

-

Math models in linguistics

-

Economics: Affects everything in your life; take a whole year of it if you can

-

Game theory