trunk-based development (TBD) continuous delivery (CD) workflow

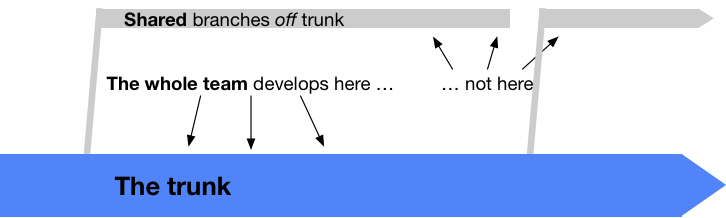

Trunk-Based Development is a source-control branching model, where developers collaborate on code in a single branch called ‘trunk’ *, resist any pressure to create other long-lived development branches by employing documented techniques. They therefore avoid merge hell, do not break the build, and live happily ever after.

Trunk-Based Development is a key enabler of Continuous Integration and by extension Continuous Delivery. When individuals on a team are committing their changes to the trunk multiple times a day it becomes easy to satisfy the core requirement of Continuous Integration that all team members commit to trunk at least once every 24 hours. This ensures the codebase is always releasable on demand and helps to make Continuous Delivery a reality.

Continuous Integration (CI) is a development practice that requires developers to integrate code into a shared repository several times a day. Each check-in is then verified by an automated build, allowing teams to detect problems early.

Continuous Delivery (CD) is the natural extension of Continuous Integration: an approach in which teams ensure that every change to the system is releasable, and that we can release any version at the push of a button. Continuous Delivery aims to make releases boring, so we can deliver frequently and get fast feedback on what users care about.

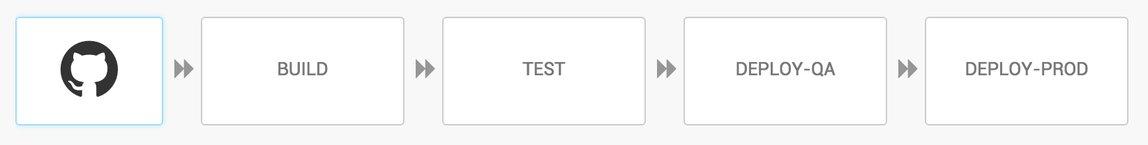

Continuous Delivery (CD) is a software strategy that enables organizations to deliver new features to users as fast and efficiently as possible. The core idea of CD is to create a repeatable, reliable and incrementally improving process for taking software from concept to customer. The goal of Continuous Delivery is to enable a constant flow of changes into production via an automated software production line. The Continuous Delivery pipeline is what makes it all happen.

The pattern that is central to Continuous Delivery is the deployment pipeline. A deployment pipeline is, in essence, an automated implementation of your application’s build, deploy, test, and release process. Every organization will have differences in the implementation of their deployment pipelines, depending on their value-stream for releasing software, but the principles that govern them do not vary

Before we talk about TBD, let us look at some of the anti-patterns with branch-based workflows.

The core principle of Continuous Integration is that of integrating code frequently. So, if you are doing development on long-lived feature branches then you are no longer integrating code with everybody else frequently enough. This means delayed feedback, big bang merges that can be risky and time consuming to resolve, reduced visibility and reduced confidence.

But working on long-lived branches adds significant risk that cannot be fixed with tooling:

Firstly, the change-set in long-lived branches tends to be large. If someone else pushes a big change then it is going to be extremely difficult and risky to merge the code. We have all seen this at some point where we had to painstakingly merge lot of conflicts.

Secondly, this pain creates a tendency to hold back on refactoring on feature branches. Developers become wary of moving code between classes or even renaming methods because of the looming fear of having to resolve merge conflicts. Inevitably, this leads to piling up of technical debt.

Thirdly, working out of long lived branches does not give a chance for other developers on the team to pick up your changes quickly enough. This affects code reuse and can also result in duplicated efforts. For example, multiple developers upgrading to a new version of a library they need. Also, there is likely no visibility on changes happening in feature branches which eliminates any feedback loop from other developers in the project until the work is pushed to master, by which time it is too late to make changes to the design.

Fourthly, notice that the feedback loop with integration pipelines is long. If you have merge conflicts leading up-to master or test failures, it can be slow and painful to resolve.

Finally, feature branches promote the tendency of big bang feature releases — “Let me add one more thing before I merge to master” — which means not only delayed integration but also delay in delivering customer value and receiving early feedback. Also, the large change-set makes it difficult to troubleshoot issues or even rollback changes in Production if things go wrong.

In short, working out of long-lived branches adds risks and friction to the process of software delivery.

One of other most common anti-patterns is to have supporting branches like Dev, QA, Staging and Production in addition to features branches. Developers work out of feature branches and merge to Dev branch when they are ready, and merge to upstream branches all the way to the Production branch. Each branch would then be configured on the CI server to run builds and deploy to a specific environment on which the feature is validated.

Apart from inheriting the problems associated with long lived feature branches, this workflow gives a false sense of security that the mainline or Production branch is pristine whereas if you look closely, it in fact introduces many new unknowns and risks.

For instance, even if you test your code exhaustively in a staging or a QA environment, there is no guarantee that the same revision is what is deployed to production. Because other changes can be made directly on any of the branches (e.g. Hot fixes for Production!) it means that what you verified on QA is not valid anymore. Merge conflicts while promoting to any of the upstream branches further reduce confidence.

In addition, because you rebuild the artifacts for every branch, there is even more risk because even small environment configuration changes can lead to differences in the binaries. For e.g. a package update or compiler version difference is enough to make the binary different from what was built previously.

In trunk-based development (TBD), developers always check into one branch, typically the master branch also called the “mainline” or “trunk”. You almost never create long-lived branches and as developer, check in as frequently as possible to the master — at least few times a day.

With everyone working out of the same branch, TBD increases visibility into what everyone is doing, increases collaboration and reduces duplicate effort.

The practice of checking in often means that merge conflicts if any are small and there is no reason to hold back on refactoring. Troubleshooting test failures or defects becomes easier when the change-set is small.

TBD also implies deploying code from the mainline to production – which means that your mainline must always be in a state that it can be released to production.

On many projects, it’s common to branch the source code to work on major new features. The idea is that temporary destabilization from the new code won’t affect other developers or users. Once the feature is complete, its branch is merged back into trunk, and there is usually a period of instability while integration issues are ironed out. This wouldn’t work if we one wants to release (once or many times) every day. We can’t tolerate huge chunks of new code suddenly showing up in trunk because it would have a high chance of taking down the canary or dev channels for an extended period. Also, the trunk can move so fast that it isn’t practical for developers to be isolated on a branch for very long. By the time they merged, trunk would look so different that integration would be difficult and error-prone.

We can (if required) create maintenance branches before each of releases, but these are really short-lived. And we should never develop directly on these branches. Any late fixes that need to go into a release are first made on trunk, and then cherry-picked into the branch.

One happy side-effect of this is that there’s no B-team of developers stuck working on a maintenance branch. All developers are always working with the latest and greatest source.

We won’t create branches, but we still need some way to hide incomplete features from users. One natural way to do this would be with compile-time checks. The problem with those is they aren’t much different from just branching the code. You still effectively have two separate codebases that must eventually be merged. And since the new code isn’t compiled or tested by default, it’s very easy for developers to accidentally break it.

We should prefer runtime checks instead. Every feature under development is compiled and tested under all configurations from the very beginning. We can have command-line flags that we test for very early in startup. Everywhere else, the codebase is mostly ignorant of which features are enabled. This strategy means that new feature work is integrated as much as possible from the beginning. It’s at least compiled, and any changes to core code that need to be done are tested and exposed to users as normal. And we can easily write automated tests that exercise disabled features by temporarily overriding the command line.

When a feature gets close to completion we introduce an option so that advanced users can start trying it out and giving us feedback. Finally, when we think the feature is ready to ship, we remove the command-line flag and enable it by default. By this time the code has been extensively tested with automation and used by many people. So the impact from turning it on is minimized.

In order to release every day, we need to have confidence that our codebase is always in a good state. This requires automated tests. Lots of automated tests. Our general rule should be that every change has to come with tests.

We must run new changes to our code against our test suite on every configuration, and we MUST enforce a “green tree” policy. If a change breaks a test, it should be immediately reverted. The developer must fix the change and re-land it. We shouldn't leave broken changes in the tree because:

- It makes it easy to accidentally land more broken changes because nobody notices the tree go from red to even redder

- It slows down development because everyone has to work around whatever is broken

- It encourages developers to make sloppy quick fixes to the get the tests passing

- It prevents us from releasing!

To help developers avoid breaking the tree, we can have try bots, which are a way to test a change under all tests and configurations before landing it. The results can be emailed to the developer. We can also have a commit queue, which is a way to try a change and have it landed automatically if the try succeeds. I like to use this after a long night of hacking. I press the button, go to bed, and wake up — hopefully to my change having landed.

Given a pretty comprehensive test coverage, we can afford to be aggressive with refactoring.

At high scale and pace, it’s critical to keep the codebase clean and understandable. We even view it as more important than preventing regressions. Engineers should be empowered to make improvements anywhere in the system. If a refactor breaks something that wasn’t exposed by failing tests, our outlook it that it isn’t the fault of the engineer who did the refactor, but the one whose feature had insufficient test coverage.

This sounds like a scary idea and many people initially balk at the idea of checking in directly to the mainline in favor of using branches which in comparison feel safe and cozy.

But don’t worry. Even the browser (chrome) that you are most likely reading this on, is being built using this practice!

While it is true that TBD expects a certain discipline from the developer, with the right practices, it can dramatically make your software development and deployment process much more reliable and lightweight.

The Continuous Delivery book mentions several best practices (below) to adopt TBD around the principle of keeping the mainline version releasable at all times:

1. Small, incremental changes over big bang changes

Frequent small changes are less risky, easier to integrate with and easier to rollback. Use branch by abstraction(not to be confused with version control branching!) to make even large-scale changes incrementally.

2. Hide unfinished functionality with feature toggles

Hide features that aren’t finished yet from users. Feature toggles are an effective way to hide new features before you are confident about releasing them to users.

3. Comprehensive automated tests to give confidence

With a comprehensive automated test suite designed to give fast feedback, you have high confidence about the changes you are making. If you are always checking in small incremental changes, test failures are easy to fix.

The deployment pipeline enables a trunk-based CD workflow. By modeling your application delivery as a pipeline of stages from the trunk all the way to Production, you get the visibility and reliability required to deploy continuously to Production.

The deployment pipeline represents the path to production

The deployment pipeline is nothing but a concept that models your build and deployment workflow as a path to production. You model the pipeline as a series of stages. Each stage can be configured to run automatically based on the success of the previous stage OR with a manual trigger. Artifacts built in one stage can be consumed in subsequent stages – giving you the confidence that the same artifact that was tested is what is being deployed.

You can see the list of commits and each commit has triggered a series of stages that lead all the way to Production. With each passing stage, you get higher confidence with that revision of the code. If something fails, the pipeline stops and you have to fix the build OR revert the commit that caused the failure. (Yes, this is inspired from Lean principles). Thus, the deployment pipeline thus affords a high degree of visibility into the build and the deployment process.

The pipeline can have any number of custom stages — including manually triggered stages — to deploy to intermediate environments like a QA or a Pre-Production (staging) environment. This way, a QA (for example) can decide to manually promote a revision to a QA environment and after verification, promote it to a production or staging environment as is the process.

This eliminates the need to have a branch per environment and enables a highly visualized and reliable workflow with trunk-based development.

Also, because there is no friction that comes with intermediate branches, this workflow promotes the practice of pushing small incremental changes that the customer benefits from continuously – which is the whole point.

In trunk based development it is different. Since we want to merge our commits into the master branch as quickly as possible, we cannot wait until the complete feature is finished. Unlike in the original trunk based development approach we still use feature branches but we have much less divergence from the master branch than in Git Flow. We create a pull request as soon as the first commit is pushed into the feature branch. Of course that requires that no commit breaks anything or causes tests to fail. Remember that unfinished features can always be disabled with feature toggles.

Now, with part of the new feature committed and the pull request created, another developer from the team can review it. In most cases that doesn’t happen immediately because the developers don’t want to interrupt their work every time a team member pushes a commit. Instead, the code reviews are done when another developer is open for it. Meanwhile, the pull request might grow by a few commits.

The code is not always reviewed immediately after the commit but in most cases it reaches the master branch much quicker than in Git Flow.

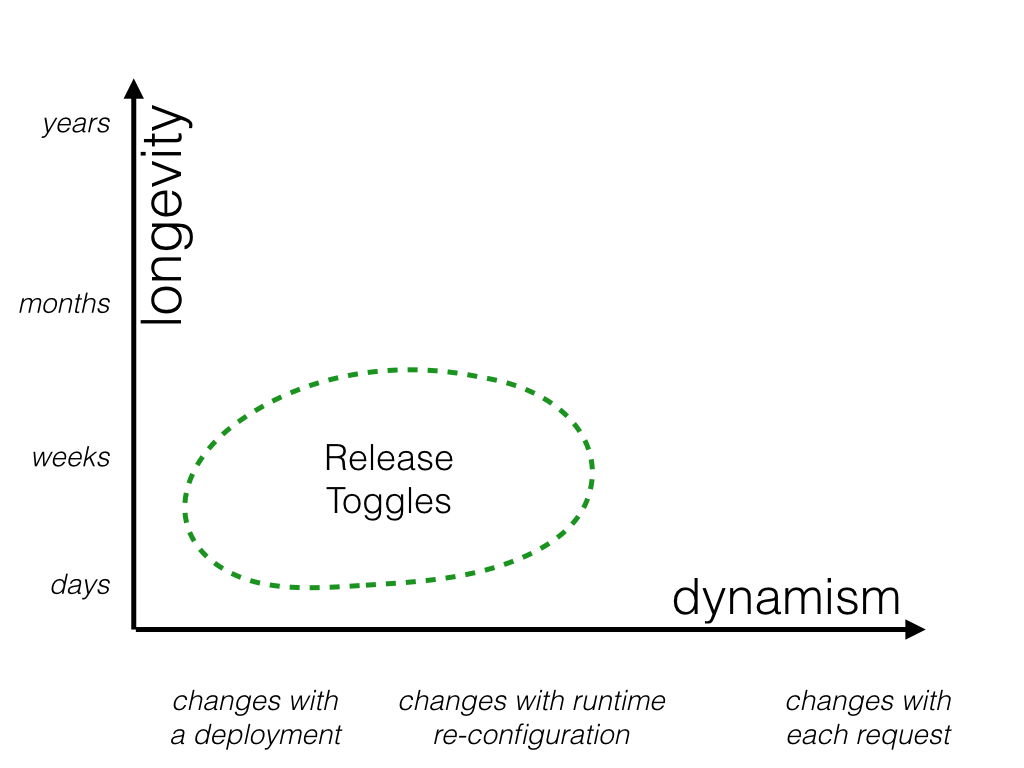

Feature toggles are a powerful technique, allowing teams to modify system behavior without changing code. They fall into various usage categories, and it's important to take that categorization into account when implementing and managing toggles. Toggles introduce complexity. We can keep that complexity in check by using smart toggle implementation practices and appropriate tools to manage our toggle configuration, but we should also aim to constrain the number of toggles in our system.

"Feature Toggling" is a set of patterns which can help a team to deliver new functionality to users rapidly but safely.

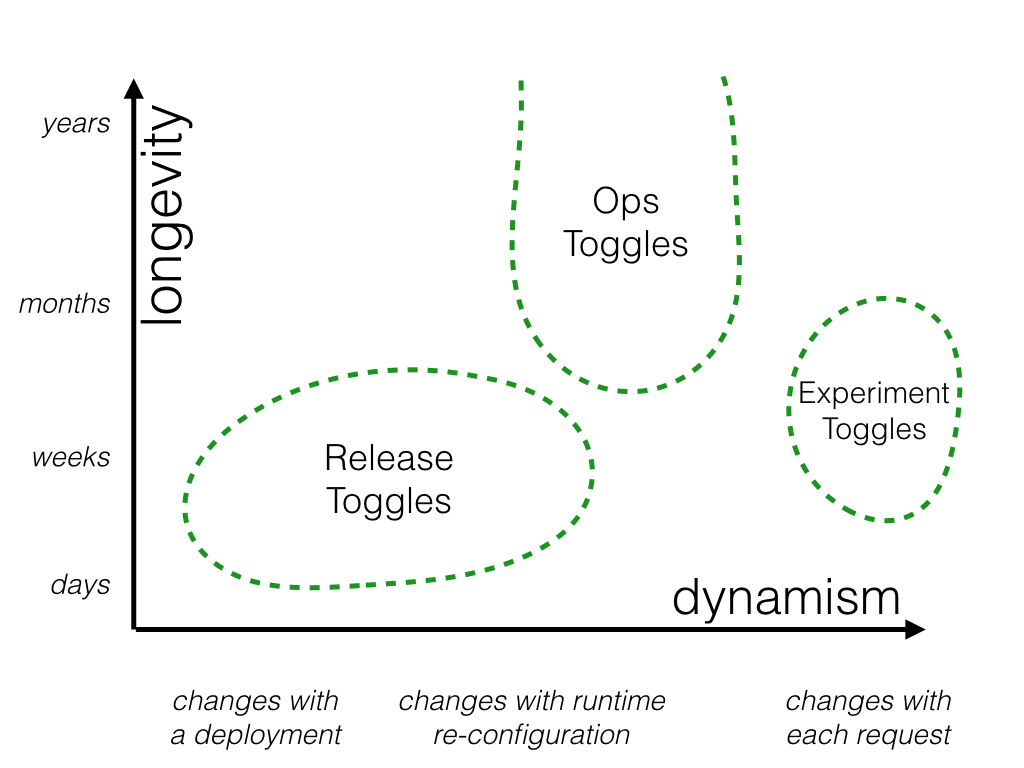

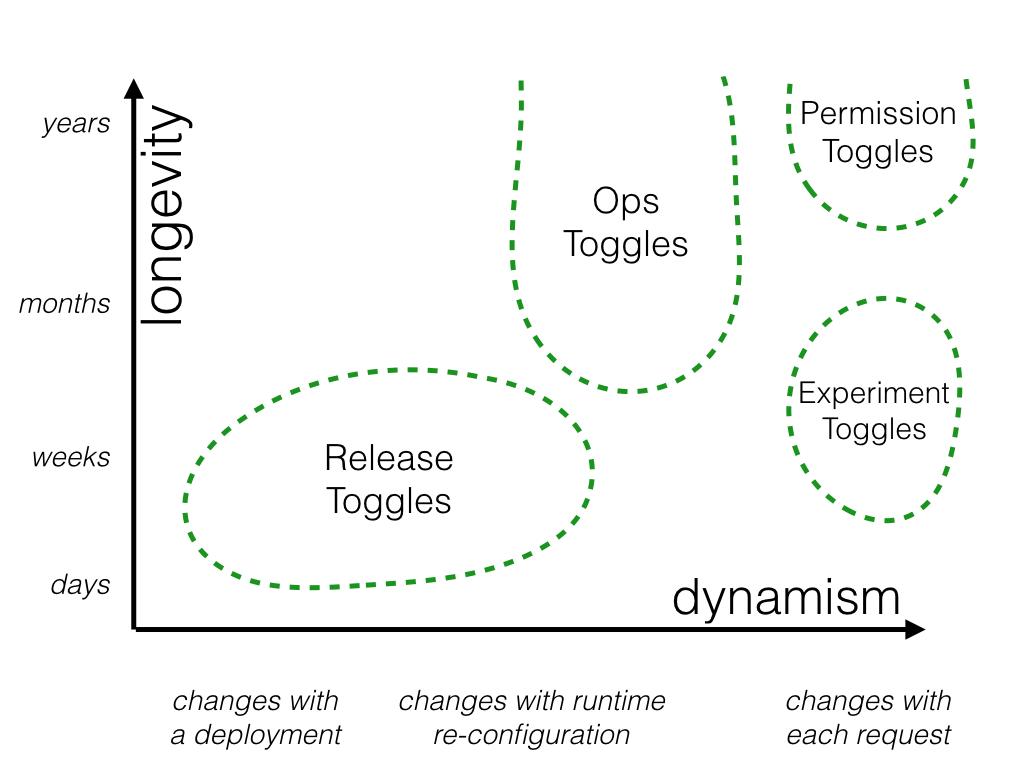

Feature toggles used to hide partly built features are called release toggles. Hodgson also identifies experiment toggles for A/B testing, ops toggles to provide controls for operations staff, and permissioning toggles to control access of features for different subsets of users

It's very important to retire release toggles once the pending features have bedded down in production. This involves removing the definitions on the configuration file and all the code that uses them. Otherwise you will get a pile of toggles that nobody can remember how to use.

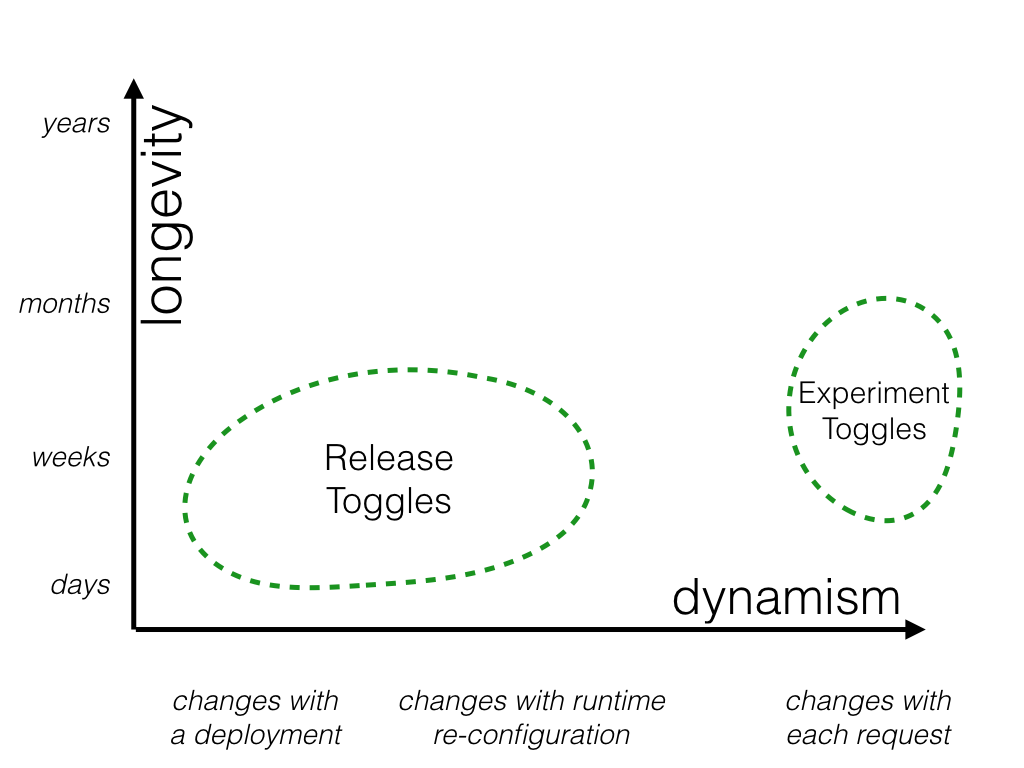

Feature toggles can be categorized across two major dimensions: how long the feature toggle will live and how dynamic the toggling decision must be. There are other factors to consider - who will manage the feature toggle, for example - but I consider longevity and dynamism to be two big factors which can help guide how to manage toggles.

These are toggles used to enable trunk-based development for teams practicing Continuous Delivery. They allow in-progress features to be checked into a shared integration branch (e.g. master or trunk) while still allowing that branch to be deployed to production at any time. Release Toggles allow incomplete and un-tested codepaths to be shipped to production as latent code which may never be turned on.

Release Toggles are transitionary by nature. They should generally not stick around much longer than a week or two, although product-centric toggles may need to remain in place for a longer period. The toggling decision for a Release Toggle is typically very static. Every toggling decision for a given release version will be the same, and changing that toggling decision by rolling out a new release with a toggle configuration change is usually perfectly acceptable.

Experiment Toggles are used to perform multivariate or A/B testing. Each user of the system is placed into a cohort and at runtime the Toggle Router will consistently send a given user down one codepath or the other, based upon which cohort they are in. By tracking the aggregate behavior of different cohorts we can compare the effect of different codepaths.

An Experiment Toggle needs to remain in place with the same configuration long enough to generate statistically significant results. Depending on traffic patterns that might mean a lifetime of hours or weeks. Longer is unlikely to be useful, as other changes to the system risk invalidating the results of the experiment. By their nature Experiment Toggles are highly dynamic - each incoming request is likely on behalf of a different user and thus might be routed differently than the last.

These toggles are used to control operational aspects of our system's behavior. We might introduce an Ops Toggle when rolling out a new feature which has unclear performance implications so that system operators can disable or degrade that feature quickly in production if needed.

Most Ops Toggles will be relatively short-lived - once confidence is gained in the operational aspects of a new feature the toggle should be retired. However it's not uncommon for systems to have a small number of long-lived "Kill Switches" which allow operators of production environments to gracefully degrade non-vital system functionality when the system is enduring unusually high load.

These toggles are used to change the features or product experience that certain users receive. For example we may have a set of "premium" features which we only toggle on for our paying customers. Or perhaps we have a set of "alpha" features which are only available to internal users and another set of "beta" features which are only available to internal users plus beta users

Release toggles are a useful technique and lots of teams use them. However they should be your last choice when you're dealing with putting features into production.

Your first choice should be to break the feature down so you can safely introduce parts of the feature into the product. The advantages of doing this are the same ones as any strategy based on small, frequent releases. You reduce the risk of things going wrong and you get valuable feedback on how users actually use the feature that will improve the enhancements you make later.

-

Raise a PR as soon as you have first commit in your feature branch -

-

No long living feature branches

-

Small, incremental changes over big bang changes

-

Hide unfinished functionality with feature toggles ( runtime switches )

-

Comprehensive automated tests to give confidence

TBD is like "github flow" but we merge into master/trunk before deploying to production

TBD is awesome, but it is not a silver bullet. Trying to implement it before having a reliable test suite and continuous integration in place (at least) will lead to serious quality issues in production.

TBD also implies deploying code from the mainline to production – which means that your mainline must always be in a state that it can be released to production.

While it is true that TBD expects a certain discipline from the developer, with the right practices, it can dramatically make your software development and deployment process much more reliable and lightweight.

One of the key technical practices that underpin this method of development, is working in "Small, incremental changes over big bang changes". Once your team embraces this practice, and the mindset behind it, you will find that your code reviews are rarely delayed more than a couple of hours. Because pull requests are very small, code reviews are very easy, so they happen more often.

You can also work with your team to prioritise continuous flow throughput. That means, if a pull request is up for review, it is effectively a blocker for someone else's progress; so everyone prioritises dropping what they are doing to do the code review as fast as they can to unblock any work clogging up.

Continuous deployment is a similar example: If you release a small amount of code to production, you have less to test, less to break and less to go wrong. And if something does go wrong, you are way more likely to understand what caused it because the changes to that environment were smaller and happened closer to the time of release, so they're easier to remember and resolve.

no branches, runtime switches, tons of automated testing, relentless refactoring, and staying very close to HEAD of our dependencies.

Q 1: So, question: how do you manage to carry out refactoring and particularly the “major modularization” without using long-lived branches, and while everything is changing so fast?

A 1: The answer is that refactorings must be broken up into changes which incrementally move toward the desired end-state without breaking anything in the meantime. It’s a skill, but it can be done!

Q 2: I’ve seen many teams losing time every day trying to fix flaky integration tests?

A 2: I don’t think there are well-known solutions. This is something the entire industry is struggling with. We should double-down on unit tests, and not write as many integration tests. We should try to design our code such that bigger and bigger pieces could be tested using the unit testing style.

Most of the content has been copied from the following references but has been presented in more structured way; if you have time then they are must read: