minikube start

minikube dashboard

minikube stop

kubectl config view

kubectl cluster-info

kubectl proxy

# This opens a proxy to kubernetes REST API

curl http://localhost:8081/

# Get the token

TOKEN=$(kubectl describe secret $(kubectl get secrets | grep default | cut -f1 -d ' ') | grep -E '^token' | cut -f2 -d':' | tr -d '\t')

# Get the API server endpoint

APISERVER=$(kubectl config view | grep https | cut -f 2- -d ":" | tr -d " ")

# Access the API Server using the endpoint and credentials

curl $APISERVER --header "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" --insecure

A Pod is the smallest and simplest Kubernetes object. It is the unit of deployment in Kubernetes, which represents a single instance of the application. A Pod is a logical collection of one or more containers, which:

- Are scheduled together on the same host

- Share the same network namespace

- Mount the same external storage (Volumes).

Pods are ephemeral in nature, and they do not have the capability to self-heal by themselves. That is why we use them with controllers, which can handle a Pod's replication, fault tolerance, self-heal, etc. Examples of controllers are Deployments, ReplicaSets, ReplicationControllers, etc. We attach the Pod's specification to other objects using Pod Templates, as we have seen in the previous section.

With Label Selectors, we can select a subset of objects. Kubernetes supports two types of Selectors:

- Equality-Based Selectors Equality-Based Selectors allow filtering of objects based on label keys and values. With this type of Selectors, we can use the =, ==, or != operators. For example, with env==dev we are selecting the objects where the env label is set to dev.

- Set-Based Selectors Set-Based Selectors allow filtering of objects based on a set of values. With this type of Selectors, we can use the in, notin, and exist operators. For example, with env in (dev,qa), we are selecting objects where the env label is set to dev or qa.

A ReplicationController (rc) is a controller that is part of the Master Node's Controller Manager. It makes sure the specified number of replicas for a Pod is running at any given point in time. If there are more Pods than the desired count, the ReplicationController would kill the extra Pods, and, if there are less Pods, then the ReplicationController would create more Pods to match the desired count. Generally, we don't deploy a Pod independently, as it would not be able to re-start itself, if something goes wrong. We always use controllers like ReplicationController to create and manage Pods.

A ReplicaSet (rs) is the next-generation ReplicationController. ReplicaSets support both equality- and set-based Selectors, whereas ReplicationControllers only support equality-based Selectors. Currently, this is the only difference.

Deployment objects provide declarative updates to Pods and ReplicaSets. The DeploymentController is part of the Master Node's Controller Manager, and it makes sure that the current state always matches the desired state.

If we have numerous users whom we would like to organize into teams/projects, we can partition the Kubernetes cluster into sub-clusters using Namespaces. The names of the resources/objects created inside a Namespace are unique, but not across Namespaces.

To list all the Namespaces, we can run the following command:

kubectl get namespaces

ClusterIP is the default ServiceType. A Service gets its Virtual IP address using the ClusterIP. That IP address is used for communicating with the Service and is accessible only within the cluster.

With the NodePort ServiceType, in addition to creating a ClusterIP, a port from the range 30000-32767 is mapped to the respective service, from all the Worker Nodes. For example, if the mapped NodePort is 32233 for the service frontend-svc, then, if we connect to any Worker Node on port 32233, the node would redirect all the traffic to the assigned ClusterIP - 172.17.0.4.

By default, while exposing a NodePort, a random port is automatically selected by the Kubernetes Master from the port range 30000-32767. If we don't want to assign a dynamic port value for NodePort, then, while creating the Service, we can also give a port number from the earlier specific range.

With the LoadBalancer ServiceType:

- NodePort and ClusterIP Services are automatically created, and the external load balancer will route to them

- The Services are exposed at a static port on each Worker Node

- The Service is exposed externally using the underlying Cloud provider's load balancer feature.

The LoadBalancer ServiceType will only work if the underlying infrastructure supports the automatic creation of Load Balancers and have the respective support in Kubernetes, as is the case with the Google Cloud Platform and AWS.

A Service can be mapped to an ExternalIP address if it can route to one or more of the Worker Nodes. Traffic that is ingressed into the cluster with the ExternalIP (as destination IP) on the Service port, gets routed to one of the the Service endpoints.

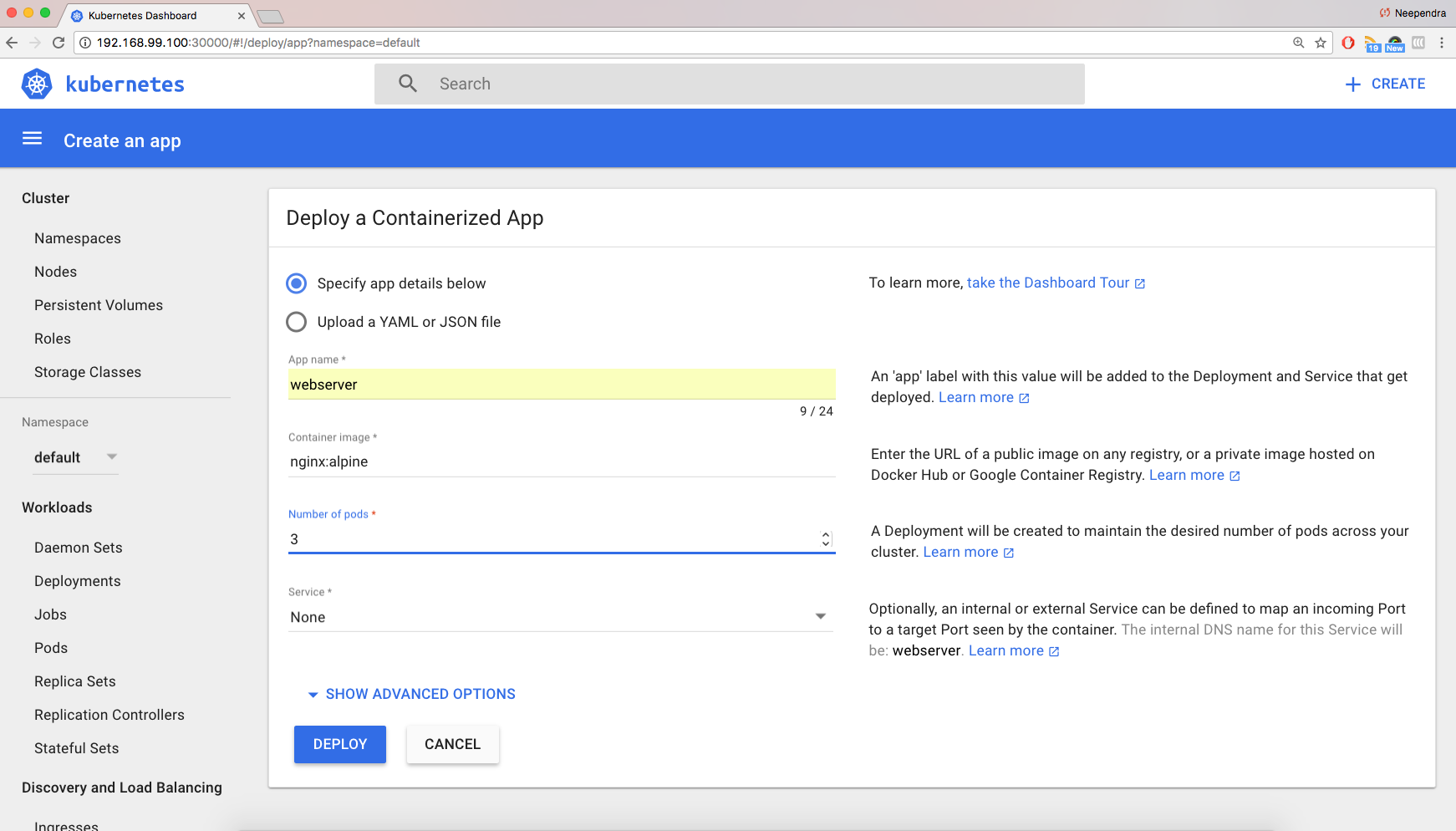

From the Dashboard, click on Deploy a Containerized App, which will open an interface like the one below:

We can either provide the application details here, or we can upload a YAML file with our Deployment details. As shown, we are providing the following application details:

- The application name is webserver

- The Docker image to use is nginx:alpine, where alpine is the image tag

- The replica count, or the number of Pods, is 3

- No Service, as we will be creating it later.

If we click on SHOW ADVANCED OPTIONS, we can specify options such as Labels, Environment Variables, etc. By default, the app Label is set to the application name. In our example, an app:webserver Label is set to different objects created by this Deployment.

By clicking on the DEPLOY button, we can trigger the deployment. As expected, the Deployment webserver will create a ReplicaSet (webserver-1529352408), which will eventually create three Pods (webserver-1529352408-xxxx).

We can also list the Deployments, ReplicaSets, and Pods from the CLI, which we created using the GUI. They will match one-to-one.

- List the deployments

kubectl get deployments

- List Replicasets

kubectl get replicasets

- List the pods

kubectl get pods

Earlier, we have seen that Labels and Selectors play an important role in grouping a subset of objects on which we can perform operations. Next, we will take a closer look at them.

We can look at an object's details using kubectl's describe subcommand. In the following example, you can see a Pod's description:

kubectl describe pod webserver-4062734599-18k26

With the -L option to the kubectl get pods command, we can add additional columns in the output to list Pods with their attached Labels and their values. In the following example, we are listing Pods with the Labels app and label2:

kubectl get pods -L app,label2

o use a Selector with the kubectl get pods command, we can use the -l option. In the following example, we are selecting all the Pods that have the app Label's value set to webserver:

kubectl get pods -l app=webserver

We can delete any object using the kubectl delete command. In the following example, we are deleting the webserver Deployment which we created in the previous section using the Dashboard:

kubectl delete deployments webserver

Using kubectl, we will create the Deployment from the YAML file. With the -f option to the kubectl create command we can pass a YAML file as an object's specification. In the following example, we are creating a webserver Deployment:

kubectl create -f webserver.yaml

kubectl create -f webserver-svc.yaml

List the services

kubectl get services

Our web-service is now created and its ClusterIP is 10.0.0.133. In the PORT(S) section we can see a mapping of 80:32636, which means that we have reserved a static port 32636 on the node. If we connect to the node on that port, our requests will be forwarded to the ClusterIP on port 80.

It is not necessary to create the Deployment first, and the Service after. They can be created in any order. A Service will connect Pods based on the Selector.

To get more details about the Service, we can use the kubectl describe command, like in the following example:

kubectl describe svc web-service

Our application is running inside the minikube VM. To access the application from our workstation, let's first get the IP address of the minikube VM:

minikube ip

Go to http://minikube-ip:the-reserved-port

A directory which is mounted inside a Pod is backed by the underlying Volume Type. A Volume Type decides the properties of the directory, like size, content, etc. Some of the Volume Types are:

- emptyDir An empty Volume is created for the Pod as soon as it is scheduled on the Worker Node. The Volume's life is tightly coupled with the Pod. If the Pod dies, the content of emptyDir is deleted forever.

- hostPath With the hostPath Volume Type, we can share a directory from the host to the Pod. If the Pod dies, the content of the Volume is still available on the host.

- gcePersistentDisk With the gcePersistentDisk Volume Type, we can mount a Google Compute Engine (GCE) persistent disk into a Pod.

- awsElasticBlockStore With the awsElasticBlockStore Volume Type, we can mount an AWS EBS Volume into a Pod.

- nfs With nfs, we can mount an NFS share into a Pod.

- iscsi With iscsi, we can mount an iSCSI share into a Pod.

- secret With the secret Volume Type, we can pass sensitive information, such as passwords, to Pods. We will take a look at an example in a later chapter.

- persistentVolumeClaim We can attach a Persistent Volume to a Pod using a persistentVolumeClaim. We will cover this in our next section.

You can learn more details about Volume Types in the Kubernetes Documentation.

In a typical IT environment, storage is managed by the storage/system administrators. The end user will just get instructions to use the storage, but does not have to worry about the underlying storage management.

In the containerized world, we would like to follow similar rules, but it becomes challenging, given the many Volume Types we have seen earlier. Kubernetes resolves this problem with the Persistent Volume subsystem, which provides APIs for users and administrators to manage and consume storage. To manage the Volume, it uses the PersistentVolume (PV) API resource type, and to consume it, it uses the PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC) API resource type.

A Persistent Volume is a network attached storage in the cluster, which is provisioned by the administrator.

Some of the Volume Types that support managing storage using Persistent Volumes are:

- GCEPersistentDisk

- AWSElasticBlockStore

- AzureFile

- NFS

- iSCSI

- CephFS

- Cinder

For a complete list, as well as more details, you can check out the Kubernetes Documentation.

PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC) is a request for storage by a user. Users request for Persistent Volume resources based on size, access modes, etc. Once a suitable Persistent Volume is found, it is bound to a Persistent Volume Claim.

After a successful bind, the PersistentVolumeClaim resource can be used in a Pod.

Once a user finishes its work, the attached Persistent Volumes can be released. The underlying Persistent Volumes can then be reclaimed and recycled for future usage.

To learn more, you can check out the documentation.

minikube ssh

mkdir vol

cd vol

echo "Welcome to Kubernetes MOOC" > index.html

pwd

kubectl create -f webserver-vol.yaml

kubectl create -f webserver-svc.yaml

With Annotations, we can attach arbitrary non-identifying metadata to objects, in a key-value format:

"annotations": {

"key1" : "value1",

"key2" : "value2"

}

In contrast to Labels, annotations are not used to identify and select objects. Annotations can be used to:

- Store build/release IDs, PR numbers, git branch, etc.

- Phone/pager numbers of persons responsible, or directory entries specifying where such information can be found

- Pointers to logging, monitoring, analytics, audit repositories, debugging tools, etc.

- Etc.

For example, while creating a Deployment, we can add a description like the one below:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: webserver

annotations:

description: Deployment based PoC dates 2nd June'2017

....

....

We can look at annotations while describing an object:

kubectl describe deployment webserver

Earlier, we have seen how we can use the Deployment object to deploy an application. This is just a basic functionality. We can do more interesting things, like recording a Deployment - if something goes wrong, we can revert to the working state.

The graphic below depicts a situation in which our update fails:

If we have recorded our Deployment before doing the update, we can revert back to a known working state.

In addition, the Deployment object also provides the following features:

- Autoscaling

- Proportional scaling

- Pausing and resuming.

To learn more, check out the available Kubernetes documentation.

A Job creates one or more Pods to perform a given task. The Job object takes the responsibility of Pod failures. It makes sure that the given task is completed successfully. Once the task is over, all the Pods are terminated automatically.

Starting with the Kubernetes 1.4 release, we can also perform Jobs at specified times/dates, such as cron jobs.

When there are many users sharing a given Kubernetes cluster, there is always a concern for fair usage. A user should not take undue advantage. To address this concern, administrators can use the ResourceQuota object, which provides constraints that limit aggregate resource consumption per Namespace.

We can have the following types of quotas per Namespace:

- Compute Resource Quota: We can limit the total sum of compute resources (CPU, memory, etc.) that can be requested in a given Namespace.

- Storage Resource Quota: We can limit the total sum of storage resources (persistentvolumeclaims, requests.storage, etc.) that can be requested.

- Object Count Quota: We can restrict the number of objects of a given type (pods, ConfigMaps, persistentvolumeclaims, ReplicationControllers, Services, Secrets, etc.).

In some cases, like collecting monitoring data from all nodes, or running a storage daemon on all nodes, etc., we need a specific type of Pod running on all nodes at all times. A DaemonSet is the object that allows us to do just that.

Whenever a node is added to the cluster, a Pod from a given DaemonSet is created on it. When the node dies, the respective Pods are garbage collected. If a DaemonSet is deleted, all Pods it created are deleted as well.

Before Kubernetes 1.5, the StatefulSet controller was referred to as PetSet. The StatefulSet controller is used for applications which require a unique identity, such as name, network identifications, strict ordering, etc. For example, MySQL cluster, etcd cluster.

The StatefulSet controller provides identity and guaranteed ordering of deployment and scaling to Pods.

Role-based access control (RBAC) is an authorization mechanism for managing permissions around Kubernetes resources. It is added as a beta resource in Kubernetes 1.6 release.

Using the RBAC API, we define a role which contains a set of additive permissions. Within a Namespace, a role is defined using the Role object. For a cluster-wide role, we need to use the ClusterRole object.

Once the roles are defined, we can bind them to a user or a set of users using RoleBinding and ClusterRoleBinding.

With the Kubernetes Cluster Federation we can manage multiple Kubernetes clusters from a single control plane. We can sync resources across the clusters, and have cross cluster discovery. This allows us to do Deployments across regions and access them using a global DNS record.

The Federation is very useful when we want to build a hybrid solution, in which we can have one cluster running inside our private datacenter and another one on the public cloud. We can also assign weights for each cluster in the Federation, to distribute the load as per our choice.

In most cases, the existing Kubernetes objects are sufficient to fulfill our requirements to deploy an application, but we also have the flexibility to do more. Using the ThirdPartyResource object type, we can create our own API objects. In this case, we will need to write a controller, which can listen to their creation/update/deletion. The controller would then perform operations accordingly.

For example, the etcd-operator uses the ThirdPartyResource to create objects, and, depending on that, its controller creates/configures/manages etcd clusters on top of Kubernetes.

ThirdPartyResource is getting deprecated with Kubernetes 1.7. A new object type called Custom Resource Definition (CRD) is getting introduced in beta with the Kubernetes 1.7 release, which will help you create new custom resources. CRD will replace the ThirdPartyResource object in the next few releases. For more details, please checkout out the example from CoreOS.

To deploy an application, we use different Kubernetes manifests, such as Deployments, Services, Volume Claims, Ingress, etc. Sometimes, it can be tiresome to deploy them one by one. We can bundle all those manifests after templatizing them into a well-defined format, along with other metadata. Such a bundle is referred to as Chart. These Charts can then be served via repositories, such as those that we have for rpm and deb packages.

Helm is a package manager (analogous to yum and apt) for Kubernetes, which can install/update/delete those Charts in the Kubernetes cluster.

Helm has two components:

A client called helm, which runs on your user's workstation A server called tiller, which runs inside your Kubernetes cluster. The client helm connects to the server tiller to manage Charts. Charts submitted for Kubernetes are available here.

In Kubernetes, we have to collect resource usage data by Pods, Services, nodes, etc, to understand the overall resource consumption and to take decisions for scaling a given application. Two popular Kubernetes monitoring solutions are Heapster and Prometheus.

Heapster is a cluster-wide aggregator of monitoring and event data, which is natively supported on Kubernetes.

Prometheus, now part of CNCF (Cloud Native Computing Foundation), can also be used to scrape the resource usage from different Kubernetes components and objects. Using its client libraries, we can also instrument the code of our application.

Another important aspect for troubleshooting and debugging is Logging, in which we collect the logs from different components of a given system. In Kubernetes, we can collect logs from different cluster components, objects, nodes, etc. The most common way to collect the logs is using Elasticsearch, which uses fluentd with custom configuration as an agent on the nodes. fluentd is an open source data collector, which is also part of CNCF.