Generate FSM, Sequence Diagram, and a set of header files from a short interface description

The "if" language is implemented here in a small Python script. This simple language is a description of a set of communicating state machines. The raw interface description (explained later on):

@Comment

this language is regular to make it so that separate implementations

are likely to mean the same thing.

all tokens are space delimited, with no token restrictions.

to be in a state means that preconditions for its In are satisfied.

The Out messages document interactions with other modules.

For Out messages, the first arg must be a module to recv the message, or

else the notification has no specific handling.

In fnName retType argType*

Out fnName retType recvr argType*

@Comment $apiName $firstState $lastState

@Module ApiG init destroyed

@Comment input message $messageName $returnType $arg1Type

@In doNotify N Z

@Comment move from one state to another: $moveName $preState $postState In $msgName $retVal $arg1

@Move consume init init In doNotify n z

@Comment module is a type, rendered as a class

@Module ApiA init destroyed

@In doSomeF F X

@In doSomeG G Y

@In setB void ApiB

@In setZ void ApiB

@Comment $messageName $returnType $recipientType $arg1Type

@Out doSomeK K ApiB X

@Out doNotify N ApiG Z

@Move constructWithB init constructing In setB b bArg

@Move waitForG constructing constructed In doSomeF f x

@Move goCrazy constructing wentcrazy In doSomeG g y

@Comment $moveName $preState $postStte Out $messageName $returnVal $recipientVal $arg1Val

@Move wasCrazy wentcrazy destroyed Out doNotify n g z

@Move moreG constructed constructed In doSomeG g y

@Move respondForK constructed responded Out doSomeK k bArg x

@Move wrapUp responded destroyed Out doNotify n g z

@Module ApiB init destroyed

@In doSomeK K X

@Out setB N ApiA ApiB

@Out doNotify N ApiG Z

@Move initializing init constructed Out setB n b a

@Move waitForK constructed constructed In doSomeK k x

@Move wrapUp constructed destroyed Out doNotify n g z

@Module ApiC init destroyed

@Out doSomeF F ApiA X

@Out doSomeG G ApiA Y

@Out doNotify N ApiG Z

@Move initializing init constructed Out doNotify n

@Move emitF constructed constructed Out doSomeF f a x

@Move emitG constructed constructed Out doSomeG g a y

@Move wrapUp constructed destroyed Out doNotify n g z

@Comment document cases that the state machine allows.

The initial state needs to be specified, but the compiler will compute the others.

@Comment $interactionName

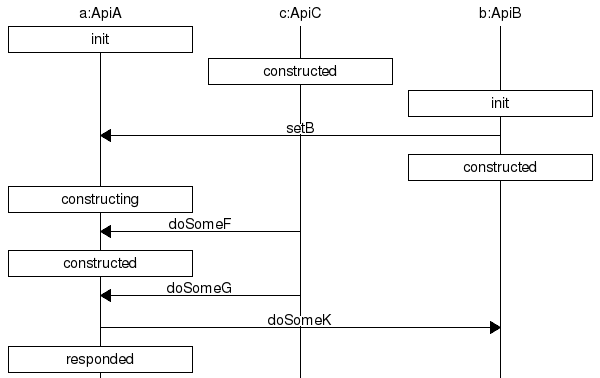

@Interaction Case1

@Comment $actorName $actorType $actorState

@Actor a ApiA init

@Actor b ApiB init

@Actor c ApiC constructed

@Comment $fromActorName $messageName $toActorName

@Send b setB a

@Send c doSomeF a

@Send c doSomeG a

@Send a doSomeK b

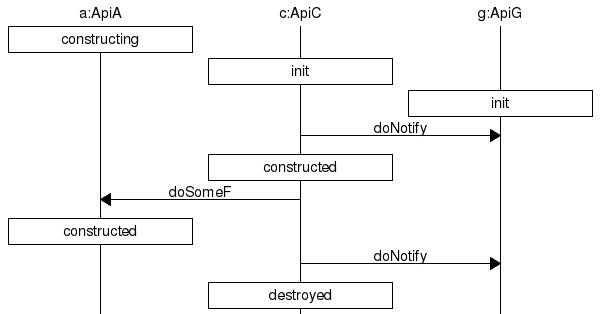

@Interaction Case2

@Actor g ApiG init

@Actor a ApiA constructing

@Actor c ApiC init

@Send c doNotify g

@Send c doSomeF a

@Send c doNotify g

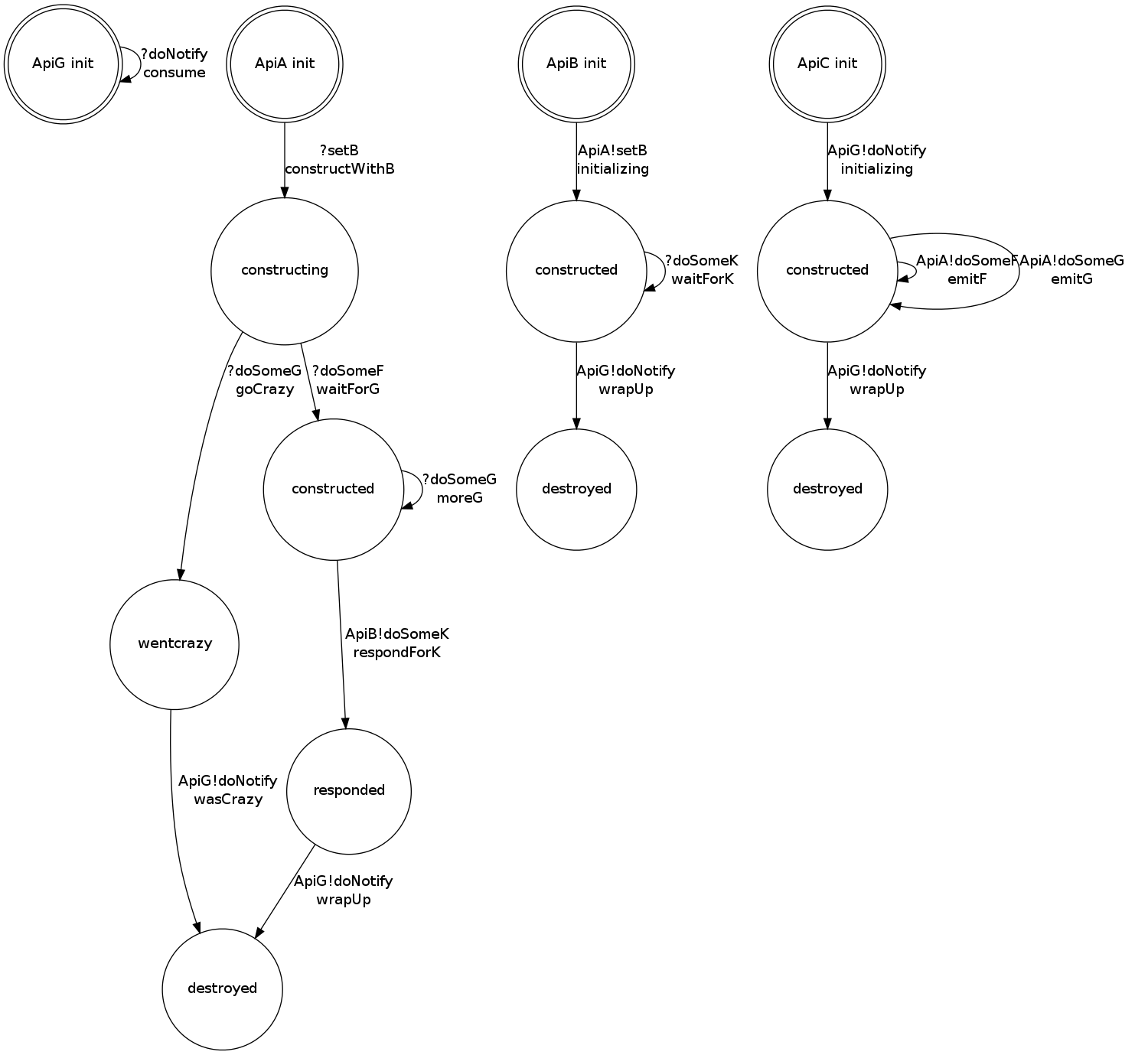

Generates these communicating state machines:

And these Sequence Diagrams (of which many could be generated, as they are instances of whatever the state machines allow):

Which generates these (currently pseudo-Java) headers:

/* Typed send API*/

public interface ApiG extends Api {

N doNotify(Z ZArg) throws PreconditionException;

boolean Precondition_doNotify(Z ZArg);

}

/* Typed send API*/

public interface ApiA extends Api {

void setZ(ApiB ApiBArg) throws PreconditionException;

F doSomeF(X XArg) throws PreconditionException;

G doSomeG(Y YArg) throws PreconditionException;

void setB(ApiB ApiBArg) throws PreconditionException;

boolean Precondition_setZ(ApiB ApiBArg);

boolean Precondition_doSomeF(X XArg);

boolean Precondition_doSomeG(Y YArg);

boolean Precondition_setB(ApiB ApiBArg);

}

/* Typed send API*/

public interface ApiB extends Api {

K doSomeK(X XArg) throws PreconditionException;

boolean Precondition_doSomeK(X XArg);

}

/* Typed send API*/

public interface ApiC extends Api {

}Which extends this fixed code:

public class PreconditionException extends RuntimeException {

public PreconditionException(String msg) {

super(msg);

}

}

/* Get a cooperating set of APIs */

public interface ApiSet {

Api[] getApis();

}

public interface Api {

void addListener(Api.Listener lsn);

/* Untyped msging API*/

Object doRcv(String msg, Object[] args);

boolean doRcv_Precondition(String msg, Object[] args);

Object doSend(Api a, String msg, Object[] args);

String[] messageNames();

String[] messageArgTypes(String msg);

String messageArgReturnType(String msg);

interface Listener {

void enter(String name);

void send(String name, String exiting, String entering,

Api target, String msg, Object[] args

);

void sendReturned(String name, String exiting, String entering,

Api target, String msg, Object[] args, Object ret

);

void rcv(String name, String exiting, String entering,

String msg, Object[] args

);

void rcvReturn(String name, String exiting, String entering,

String msg, Object[] args,Object arg

);

void exit(String name);

}

}The rendering to headers is something that is still being decided. Ultimately, the goal is to have it be generated such that only legal state transitions can be expressed.

-

The reason that preconditions are included is that when every input has a well defined precondition function, we can safely invoke random API methods as long as the preconditions are satisfied.

-

Such a random invoker of the API set can be used to test the APIs, even without an implementation beyond precondition checks and state transitions.

-

The explicit inclusion of state machine transitions allows the API to really be documented. In this way, it is even decideable by a machine whether usage is correct, in the sense that the API will not succumb to abuse from its callers.

-

With all precondition checks moved out explicitly, and all state transitions explicitly handled with callbacks, all logging at interface boundaries can be moved out to a proxy that implements this interface and forwards to the implementation. At runtime in production, the proxy might be removed; as normal practice for assertion handling.

As an example of how to test it:

void testApiSet(ApiSet apis, Api.Listener logger) {

//Log all communications that are going to happen

for(ApiSet api : apis.getApis()) {

api.addListener(logger);

}

//Sit in a loop sending arbitrary messages between APIs api1 to api2

for(ApiSet api1 : apis.getApis()) {

for(ApiSet api2 : apis.getApis()) {

for(String msg : api2.messageNames()) {

if(api2.doRcv_Precondition(msg, null)) {

api1.doSend(api2, msg, null);

}

}

}

}

}Note that all interface related handling can stay in the interface, and this includes precondition checks and state transitions.

//The implementation doesn't bother with internal precondition checks

ApiB bUndefendedImplementation = new ApiBImplementation();

//throws exceptions when attempts are made to violate preconditions

ApiB BProtocolEnforcer = new ApiBEnforcer(bUndefendedImplementation);

//This wrapper logs all activity

ApiB bProtocolLogger = new ApiBProtocolLogger(bProtocolEnforcer);

//The call is logged, and the raw implementation is defended by the proxy

aProtocolLogger.doSend(bProtocolLogger, "doSomeK", null);When dealing with writing Object Oriented code, little attention is currently paid to the fact that each object has state, where each function in that API has preconditions that restrict the allowable calling order for the methods in that API. Having such well defined ordering gives us what is called a Protocol.

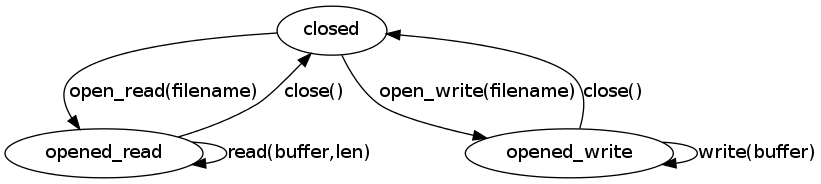

This says that even though this stateful file API consists of a few functions:

- open_read(filename)

- open_write(filename)

- read(buffer,len)

- write(buffer)

- close()

The order of the API matters because it is stateful. Implicitly, there are preconditions on every function in the API. These preconditions can be modeled as type state. So the preconditions via type state determine all legal calling orders. The compiler should be able to check that a calling order is actually legal.

When there are multiple such state machines involved, they call each other. Most interface definition languages stop at the function being called, and do not state who makes the call. Without this information, it cannot be decided whether sequence diagrams are correct usages of the APIs. Including a sender and explicit receiver gives a model similar to CSP or the Actor model. It is important to note that this notation differs from CSP in that the send and receive are asynchronous. When one API calls another, it will simply wait until the other API gets around to consuming the message. In CSP, send and receive must be simultaneous, and result in deadlock when a one of the state machines that can handle a message is not in a state where it can do so.

When this ordering is exactly defined such that the compiler can reject all unforeseen uses, the API has a new layer of defense, by denying the attacker a space of undefined states for it. This is very similar to the concept of LANGSEC, where input must be recognized as being in the language of the API before it will be parsed. In this view, the correct message ingest of actors must be decideable. APIs are treated similar to Communicating Sequential Processes (CSP). Each instance of an API has state, and they exchange messages through their input message queue.

The script is similar in concept to Ragel, except it is explicitly modelling interactions between isolated state machines. Without this, sequence diagrams cannot be enforced.

The basic rule is to never invoke any function until the preconditions for the invoke are met. That means that not only are the input types satisfied, but that preconditions take input values into account and the current state of the API. In this view, the states in the state machine really represent the preconditions that must be true, in combination with expected interactions with other APIs.

Because of this, the API is modeled as message passing state machines. Every transition in the state machine either ingests an input message (transforming from its precondition to its postcondition), or emits an output message (transforming from its precondition to its postcondition). In this way, we capture all externally observable state changes in a state machine. This is enough information to automatically generate:

- The header files for each module (Java-like interfaces for this POC)

- The overall communicating state machines

- Include required traces in the interface definitions themselves

- Proxy the modules so that all pre and post condition checks can be moved into the proxy and completely out of the implementation

- Proxy the modules so that evan blank stubs can pass behavioral unit tests

- Proxy the modules so that logging can go there (logging all message passing and state transitions) rather than in the implementation code

- The full dependency diagram between components. What we import is just as important as what we export.

We assume that if a function is ever invoked before its preconditions are met, that it crashes after exposing a horrible security vulnerability. The postconditions and explicitly handling message sending (rather than only noting what an API will accept) are the parts that are usually missing from interface definitions. Without them, we have to stop being explicit at defining callable functions; and get into drawing ambiguous diagrams that are not machine checkable.

-

Only given a set of C header files with weak types, we can impose interfaces between modules. But the interfaces end up being extremely ambiguous.

-

In Object Oriented programming without DesignByContract we get partially supported Protocols because the type systems enforce some of the preconditions for every function. Using strong types alone, we can come close to imposing a regular expression grammar over the allowable sequence of calls to an API. But we still can't reach the ideal of disallowing the call of a function with unmet preconditions.

-

With DesignByContract, we get quite a bit closer because we can ensure that no function with unmet preconditions gets invoked, while also implying what the next state needs to be. Without the postconditions, we can't define the state machines. Without state machines, we can't check the sequence diagrams.

-

With Typestate (the approach taken here), the preconditions are implicitly hidden in the state machines. Each distinct state is not a configuration of all variables in the API, but are externally distinguishable pre and post condition combinations.

-

DependentTypes are the ideal, where the type system itself is strong enough to specify pre and post conditions exactly. With dependent types, the type depends on the value of the object. This is the fullest power available, such that code can be proven logically consistent. No attempt to use dependent types is made. But note that DesignByContract provides a weak form of it that has many of the same advantages.

The "if" language is as simple as it can possibly be from a parsing perspective. The language is completely regular, meaning that it can be parsed by a regular expression. It does this by avoiding the need to balance nested constructs (begin, end, etc). Variable length lists of things are always placed last to keep the grammar regular. That means that return values are no optional, and parameters get specified last.

An "if" file is a sequence of modules and interactions, with keywords having an ampersand to mark them.

This is a module named ApiA with start state init and final state destroyed. The name is a type name that will end up being the interface name for the module.

- @Module ApiA init destroyed

When a module is being defined, an input message with name, return type, arg types are specified:

- @In doSomeF F X

- @In doSomeG G Y

- @In cosine floatFromMinusOneToPlusOne float

The input messages are literally the functions that get invoked on the API. Almost every methodology stops here; which is why state machines and interaction diagrams are markerboard-only phenomena that don't survive into the code. The dual of @In messages is the @Out messages. With them, we are able to encode how modules depend on each other, and are able to literally check interactions for overall correctness (such that no module tries to use another modules function in a way that violates its preconditions).

It is similar except between the type declaration for the return type and the args, in insert the type of the receiver (ie: self):

- @Out doSomeF F ApiA X

- @Out doSomeG G ApiA Y

- @Out cosine floatFromMinusOneToPlusOne ApiA float

When one state machine invokes an @Out, the call blocks until the receiver state machine transitions on its @In. This is slightly different from CSP here. We assume that all actors simply consume an input message queue, and one @Out corresponds to one @In. @In corresponds to code executing as the state machine transitions from pre to post state as it parses input. @Out corresponds to code executing as the state machine transitions from pre to post state as it sends the input.

These @In and @Out functions just represent the messages being sent with no regard for the state machines. The @Move is an instance of a usage of either an @In or an @Out giving the specific pre and post states. Again, because the "if" language is regular, the function call is placed last because of its variable length.

This means that there is a transition called "respondForK" that moves from the constructed to the responded state, and will invoke bArg's message doSomeK(x) and call the result k.

- @Move respondForK constructed responded Out doSomeK k bArg x

In messages corresond to places where the API blocks and is stuck waiting for input from the outside. Out messages correspond to event handling hooks. When moving through a state machine, these are all distinct concepts with different listeners:

- Exit pre state

- Move to post state invoking f

- f is invoked

- Enter post state

Interactions are an addition to modules that exist to give names to sequences of events between actors, and to be able to check that they are possible. We are here specifying the overall correctness of the system. It would also be here we we would specify state transitions to ensure that some sequences put the API into the destroyed state.

There should be a notion of @Spawn such that the entire system can be specified to include the top level program that instantiates the objects and injects their dependencies into each other to get them started. I have done this with some hand created dot files, but not accounted for this in the grammar.

This is all conceptually similar to Erlang, which uses tail recursion to specify regular state machine changes (and non-tail calls create a sub-state machine). There, everything is communicating state machines, and explicitly modelling spawn dramatically simplifies reasoning about how the system is wired together.