Complex data-driven processes can usually be be broken down into different stages. Also, each of these stages can be broken down into small tasks that can run in parallel. This leads to the idea of decomposing a bigger process into a smaller tasks organized in a directed acyclic graph (DAG). For example, in assisted driving systems (keep lane or speed, platooning, etc) the process consists in collecting data from sensors, filtering data, performing sensor fusion (combining data from different sensors to reduce uncertainty), taking decisions based on data and sending information to actuators, if necessary. This process must be cyclicly performed in real-time constraints, several times per second to react in time in case some urgent action must be taken.

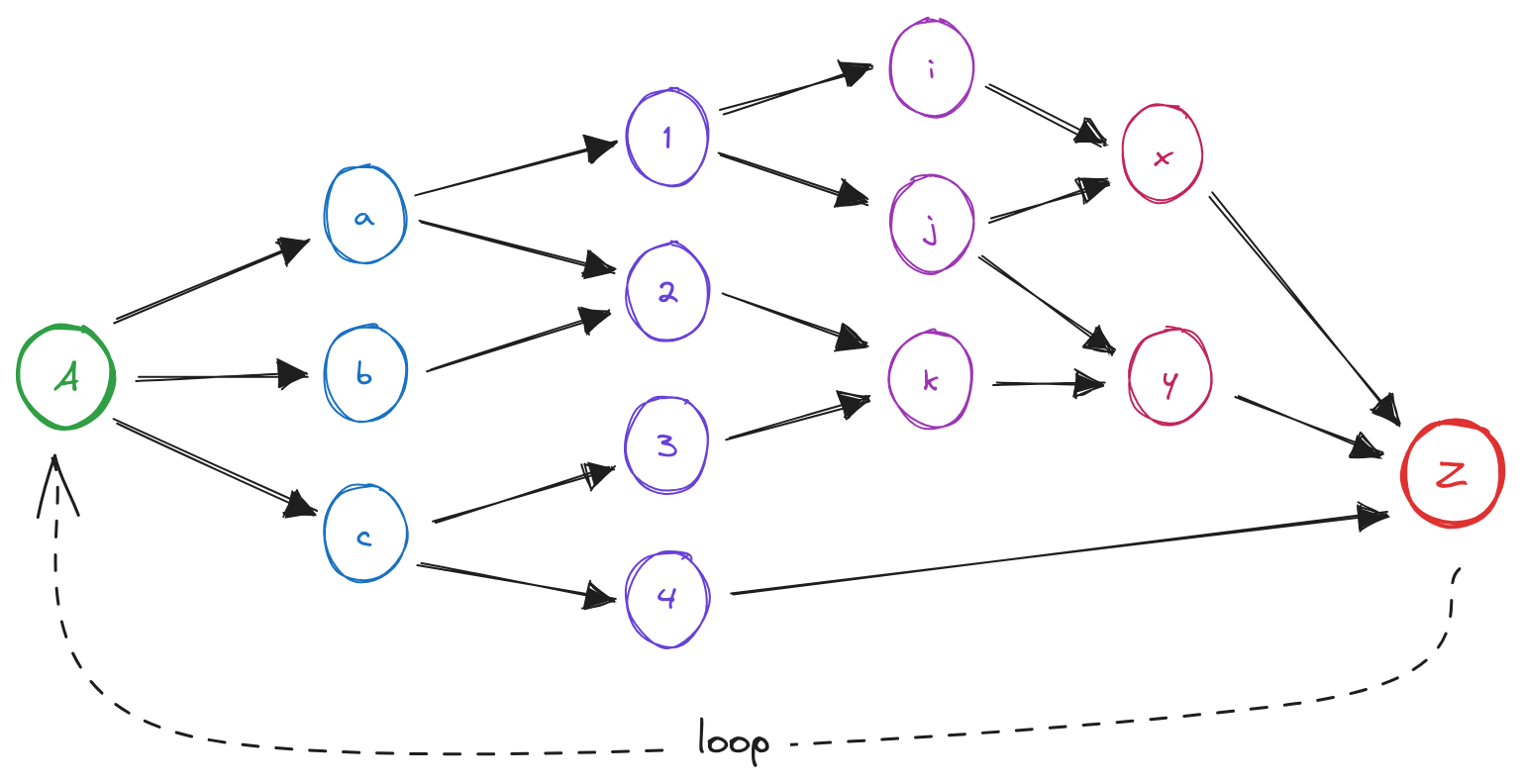

This is an example of a DAG with a number of tasks organized in four stages (colors):

In a DAG, no task can start if the parents have not been finished. In the

example, task

Given a DAG and a number of CPU threads, finding the best scheduling

assignment of a DAG into CPU threads is an

This implementation represents a DAG as a

- node label:

$A$ ,$1$ ,$x$ , etc - list of connected nodes: the children, e.g.

$A\rightarrow \{ a, b, c \}$ - list of connecting nodes: the parents, e.g.

$y\rightarrow \{ j, k \}$ - pinter to a function: the task that the node represents

- number of required dependencies: number of parents connecting the node (topologically)

- number of satisfied dependencies: number of parents that have finished their execution (at run time)

Nodes

The simulation environment allows you to specify the amount of time required by each task (in ms). All simulated tasks simply wait for the specified amount of time. This means that tasks are not consuming CPU time, which is important when simulations are performed in a single CPU core. In other words, it is possible to have a multiple-threaded application really running in parallel in a single CPU core if threads are simply sleeping.

DAG nodes that can be triggered are put in a queue of tasks. In other words, a task can be triggered if the number of satisfied dependencies is equal to the number of required dependencies. This guarantees the task precedence defined by the DAG.

In this implementation, a proactive runner is a

- wait for a task (DAG node) to be appended in the queue of tasks

- get the first task of the queue

- set the number of satisfied dependencies to zero (for the next loop)

- run the function associated to the DAG node

- for an intermediate node (other than

Z): for all node children, increment the number of satisfied dependencies- if this number is equal to the number of required dependencies, then append the child node to the queue of tasks

- for the final node

Z: either finish the execution of the DAG (depending of the number of completed loops) or append the nodeAto the queue of tasks to start a new loop

In the presented scenario there is no need to create a scheduling algorithm.

Typically, this would require a list of task to be executed by each runner.

Here, task

To check that this works, an execution trace can be printed at the end of each

DAG loop. The trace consist in a a sequence of node labels. Each node appends

its label when it task starts, and again when the task finishes. Thus, it's

easy to check the validity of a DAG loop by looking at the trace and making

sure that no child is started before its parent(s). For example,

AAabca1c341ij3b2j4ix2kxkyyZZ is a valid trace for that DAG of the figure.

To simplify things, the duration of all tasks when ran in sequence is 1 second. Adjusting the parameters to 1 runner and 10 loops, the execution time of the program is slightly greater than 10s due to the small, almost negligible overhead of creating the DAG and the proactivity of the runners.

Thess are the values obtained in a powerful 16-core x86_64 CPU:

| Runnners | Avg. Time |

|---|---|

| 1 | 10.02 |

| 2 | 5.34 |

| 3 | 4.20 |

| 4 | 4.01 |

| 5 | 4.01 |

| 6 | 4.01 |

It is important to note that DAGs have an inherent parallelization degree, meaning that there is a maximum number of nodes running in parallel. Adding more runners to the pool does not reduce the execution time of a DAG loop. In this case, it's easy to see that the optimal number of runners is 4.

Because simulated tasks only wait for the specified number of ms and don't consume CPU, running the same simulation in a modest single-core riscv-64 CPU gives similar results:

| Runnners | Avg. Time |

|---|---|

| 1 | 10.42 |

| 2 | 5.36 |

| 3 | 4.23 |

| 4 | 4.04 |

| 5 | 4.04 |

| 6 | 4.04 |

Note: Just to give you a comparative idea of both CPUs, compilation time of the file

graph.cis 50 times faster in the powerful one.

Results obtained intuitively show that the overhead introduced by proactive runners is not so big. The case of the riscv-64 CPU is different because the single CPU has to simulate all threads. With only one runner, a 4% of additional time is added, but this includes the DAG creation and initialization. Better time measurements must be implemented to have accurate results (TODO).

This simulation method can be used to evaluate the parallelization degree of a DAG and assign the optimal number of runners. Also, a refined implementation that keeps time measures in the DAG nodes can be used to find the critical path, traversing the DAG in reverse looking for the most time consuming nodes.

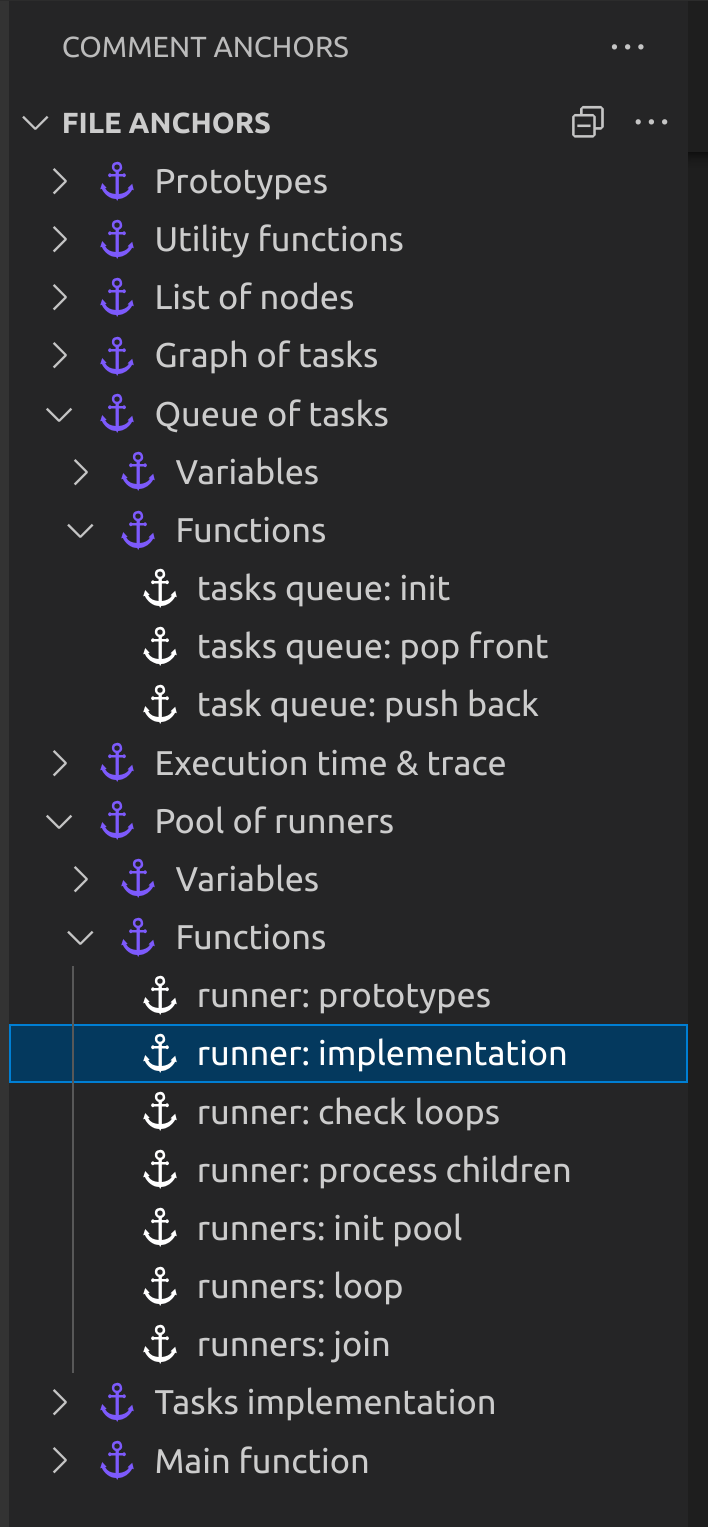

This implementation has been put in a single file intentionally. Otherwise, a set of modules in a separate files would be a much a more convenient organization.

But, if you use vscode and the extension Comment

Anchors,

then you will have an easy way to navigate and understand code:

There is no included build script, simply gcc graph.c -O3 -o graph and run it.

Not yet implemented:

- Add command line arguments to select the number of loops and runners.

- Measure overhead introduced by runners management in the DAG loop execution.

- Find the critical path: traverse the DAG in reverse, from

$Z$ to$A$ and, according to the ending time of each task, select the path with higher duration.

MIT (c) 2023 Francesc Rocher