Dimple is a simple SAT solver written in Java. This is an attempt at learning about the Boolean Satisfiability Problem and along the way getting better at Java.

Dimple can be built with gradle. To build Dimple and run its unit tests, run

gradle build on the command line. Dimple requires Java 11.

Dimple comes with a command line script to allow easy usage. The tool is

surprisingly called dimple, and receives its input as an s-expression on

stdin:

$ cat file.lisp

(and

(or A B (not C))

(or B C)

(not B)

(or (not A) C))

$ dimple file.lisp

SAT

true = { A C }

false = { B }

Supported s-expression functions are not, or, and, if, and iff.

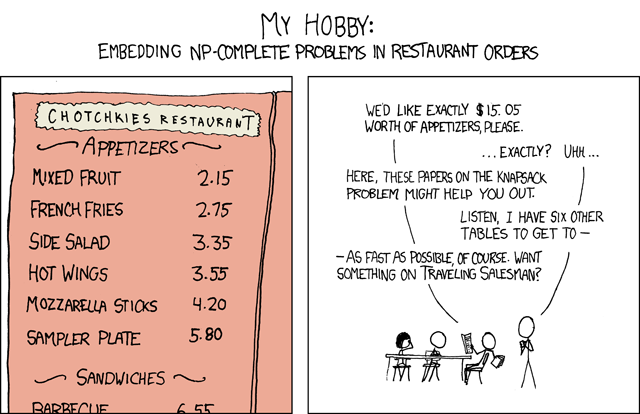

What is SAT, and why does it need solving? SAT is short for SATISFIABILITY, which is short for the Boolean Satisfiability Problem. This is the problem of determining if there is a set of assignments for which a given boolean formula is true. That's quite a mouthful, so lets try to clarify it a bit with an example:

Given the boolean formula (A or B or -C) and (B or C) and -B and (or -A C),

are there true or false assignments for A, B and C for which this formula

evaluates to true? Answer in this case is yes, there is only one assignment,

A -B C. Another example, in this case not satisfiable is

A <=> B and A and -B.

Minor caveat: GitHub does not support LaTex for its readme files, so

mathematical notation has been replaced with my own pseudo-notation. Variable

names are capital letters, A dash (-) before a variable name means it is

logically negated, the words and and or correspond to their boolean

logic counterparts, and the symbols -> and <=> correspond to logical

implication and a logical biconditional respectively.

SAT is a hard problem, in fact, it has been proven to be NP-Complete. That is,

there will never be an algorithm which solves SAT in less than 2^N operations,

where N is the number of variables. Most SAT solvers try to achieve a runtime

performance of 2^c*N, where c is some constant smaller than 1. The fastest

(?) known algorithm for SAT is PPSZ, which has a runtime complexity of

O(2^0.386*N).

Dimple's SAT solver is an implementation of Knuth's SAT0W program. It is a watch-list based algorithm, which allows for trivial backtracking.

Dimple is capable of solving SAT problems in CNF form. CNF is short for

Conjunctive Normal Form, or layman's terms, an "and of ors". CNF is a set of

sets of variables connected by ors, which in turn are connected by ands.

This means that in order to solve the SAT, our assignment needs to satisfy at

least one variable in each clause. An example of a formula in CNF form is

(A or B) and (A or C), whereas A and (-(A <=> B) or C) is not, because of

the negation and biconditional.

Before we begin solving the SAT problem, we need to devise a way of encoding it. We need a way to be able to work with our clauses that will allow us to check if a variable in a clause is negated or not, and a way to traverse the clauses easily.

For this I chose to use a Set<Integer> for each clause, making the entire

problem a Collection<Set<Integer>>. A variable will be encoded as a number

between 1 and N, N being the number of all variables. To remember which

variable corresponds to which number, a BiMap<String, Integer> is used. This

allows us to encode the entire problem using these two data structures.

Our set of integers currently does not know whether or not an variable is

negated. For this another trick must be applied. We save the variable v as

x = v << 1 | sign(v) in the set. sign(v) returns 1 if v is negated and

0 otherwise. This allows us to query the variable easily with x >> 1 and

query its sign with x & 1.

We can look at a SAT as the set of all assignments to a certain formula, and to

list them we can simply iterate through said set, printing them out one by one.

For this Dimple implements an

AssignmentIterator class which

implements Iterator<Boolean[]>. Java's Iterator interface will allow us to

simulate this iteration through the set of all assignments. Iterator must

return a value for each invocation of next(), and we cannot know if another

solution to the SAT exists without trying to find one. Thus, the last solution

our iterator will return will always be a bogus one. If our iterator returns

only one solution, the formula is unsatisfiable.

Dimple's algorithm is a backtracking one. Starting from variable 0, we assign

true or false to all variables up to variable n-1. The entire search space

is of course O(2^N), but hopefully we will terminate the algorithm before

searching through it all (assuming there is a solution). The assignment is an

array of Booleans, with values true and false for variables which have

been assigned a value, and null when they have not. When backtracking, a

variable is set to null to indicate that it has had its assignment removed.

The next construct we need to initialize is the watch-list. The watch-list is what enables us to trivially backtrack and I will go into its intricacies later. The watch-list is a list mapping variables to clauses in which they reside. A clause is considered watching a variable, when said variable maps to the clause in the watch-list.

private List<Deque<Set<Integer>>> createWatchList() {

List<Deque<Set<Integer>>> watchList = Stream.generate(() -> new ArrayDeque<Set<Integer>>())

.limit(2 * variables.size())

.collect(Collectors.toList());

for (var clause : clauses) {

var any = clause.iterator().next(); // get any variable from the clause

watchList.get(any).add(clause); // make the clause "watch" said variable

}

return watchList;

}

AssignmentIterator( /* ... */ ) {

// ...

this.currentAssignment = Stream.generate(() -> null)

.limit(variables.size())

.toArray(Boolean[]::new);

this.watchList = createWatchList();

this.currentVariable = 0;

this.state = Stream.generate(() -> 0).limit(variables.size()).toArray(Integer[]::new);

}The AssignmentIterator will attempt to assign values to all variables in

order, following a set of rules:

- All watched variables have either been assigned

true, or have not been assigned yet. - When assigning a variable

Vtotrue, clauses watching-Vmust now watch another variable. Conversely, when assigningVtofalse, clauses watchingVare now required to watch another variable. - If an alternative variable is not found, we have a contradiction and must backtrack.

- When we have backtracked all the way to the first variable, we know we have exhausted all possible assignments and can terminate.

private boolean findAlterantive(final int falseVariable) {

boolean foundAlternative = false;

var clause = watchList.get(falseVariable).getFirst();

for (var alternative : clause) {

var variable = alternative >> 1;

var isFalse = (alternative & 1) > 0;

if (currentAssignment[variable] == null || currentAssignment[variable] != isFalse) {

foundAlternative = true;

watchList.get(falseVariable).removeFirst();

watchList.get(alternative).add(clause);

break;

}

}

return foundAlternative;

}

private boolean updateWatchList(final int falseVariable) {

while (!watchList.get(falseVariable).isEmpty())

if (!findAlterantive(falseVariable))

return false;

return true;

}The watch-list approach provides us with a very convenient feature: when

backtracking, assignments go from true or false to null. According to

rule #1, null is a legal state for the watching clause, which in turn means

that we do not need to update the watch-list when backtracking, only the

assignments.

Finally, all we need to do now is, for each variable, try to assign true or

false to it, and if successful move on to the next. If unsuccessful, assign

null and try to reassign the previous variable. Here I introduce a state

property which keeps track of which values have been tried for each variable.

private boolean tryUpdate() {

boolean triedUpdate = false;

for (var value : new int[]{0, 1}) {

if (((state[currentVariable] >> value) & 1) == 0) {

triedUpdate = true;

state[currentVariable] |= 1 << value;

currentAssignment[currentVariable] = value != 0;

if (!updateWatchList(currentVariable << 1 | value))

currentAssignment[currentVariable] = null;

else {

currentVariable += 1;

break;

}

}

}

return triedUpdate;

}Once we have assigned all of the variables, we can return an assignment, and if

we have backtracked all the way to the beginning, we can terminate the

algorithm as all assignments have been exhausted. In AssignmentIterator,

assignments are saved to a list where they can later be retrieved.

private Boolean[] nextAssignment() {

while (true) {

if (currentVariable == variables.size()) {

currentVariable -= 1;

return currentAssignment;

}

if (!tryUpdate()) {

if (currentVariable == 0) {

hasNext = false;

return null;

} else {

state[currentVariable] = 0;

currentAssignment[currentVariable] = null;

currentVariable -= 1;

}

}

}

}Now that we have a way to encode and solve a SAT problem, lets make the program do the encoding for us. Additionally, lets explore the possibilities of solving problems not structured as CNF.

To support s-expressions, we need a way to parse them and transform them into Dimple's encoded clauses. Parsing s-expressions is simple, an s-expression is a list of either strings, which we call Atoms, or more s-expressions, forming a sort of tree. In Java we can implement an s-expression like so:

class Sexpression extends LinkedList<Either<String, Sexpression>> {}Peter Norvig provides a

simple s-expression parser on his website,

which can easily be adapted to parse strings into our Java s-expression class.

All it does is replace ( with (, and ) with ) and split the string

on whitespace. The split string is then recursively parsed into our

Sexpression class. See

SexpressionParser for the

full code.

S-expressions allow us to express problems in a more natural way than CNF. Every non-CNF boolean logic formula (prepositional formula) can be converted into a CNF equivalent, the only caveat is that the CNF equivalent lead to exponential explosion of the formula.

Converting to CNF is done with in following steps:

- Replace biconditionals

P <=> Qwith(P or -Q) and (-P or Q). - Replace implications

P -> Qwith(-P or Q). - Propagate all negations inward by applying De Morgan's law. Replace

-(P and Q)with-P or -Qand-(P or Q)with-P and -Q. - Distribute

ors inwards overands. ReplaceP or (Q and R)with(P or Q) and (P or R).

To do this in Dimple, s-expressions are parsed into an intermediate format I

call a Formula. A Formula is a tree like structure which corresponds to an

s-expression but allows easier traversal and transformation using a Visitor

Pattern:

public interface Formula {

public <T> T accept(FormulaVisitor<T> visitor);

}The visitor pattern enables separation of algorithms and data. It allows us

to implement various transformations on the Formula class without modifying

the class source code in order to support them. A simple example can be found in

the

FormulaToStringVisitor

class, returns a string representation of a Formula.

Back to our subject, the

CnfConverter class applies

four visitors, one for each step, which do the conversion:

public class CnfConverter {

public static Formula convert(Formula formula) {

formula = formula.accept(new BiconditionalEliminationVisitor());

formula = formula.accept(new ImplicationEliminationVisitor());

formula = formula.accept(new NotPropagationVisitor());

formula = formula.accept(new OrOverAndDistributionVisitor());

return formula;

}

}Clauses can be created using another visitor. ClauseVisitor is applied to each

or clause encountered in the visitation process, which collects variables into

clauses and finally returns a clause.

class ClauseVisitor extends FormulaVisitor<Set<Integer>> {

Map<String, Integer> variables;

ClauseVisitor(Map<String, Integer> variables) {

this.variables = variables;

}

@Override

public Set<Integer> visit(Atom.Var formula) {

String variable = formula.value;

variables.computeIfAbsent(variable, (k) -> {

return variables.size();

});

return Set.of(variables.get(variable) << 1);

}

@Override

public Set<Integer> visit(UnaryConnective.Not formula) {

Atom.Var atom = (Atom.Var)formula.argument;

String variable = atom.value;

variables.computeIfAbsent(variable, (k) -> {

return variables.size();

});

return Set.of((variables.get(variable) << 1) | 1);

}

@Override

public Set<Integer> visit(BinaryConnective.Or formula) {

var result = new HashSet<Integer>();

result.addAll(formula.left.accept(this));

result.addAll(formula.right.accept(this));

return result;

}

}SAT is an interesting problem and has been extensively studied over the years. SAT solvers have become increasingly better and can scale to millions of variables. Many known difficult problems can be reduced to SAT, so having a good a SAT solver enables us to solve sometimes completely unrelated problems. The solver need not know anything about the problem, only how to transform it into a SAT instance and how to transform the solution to something relevant to the problem. Let's look at a few problems which we can solve with a SAT solver.

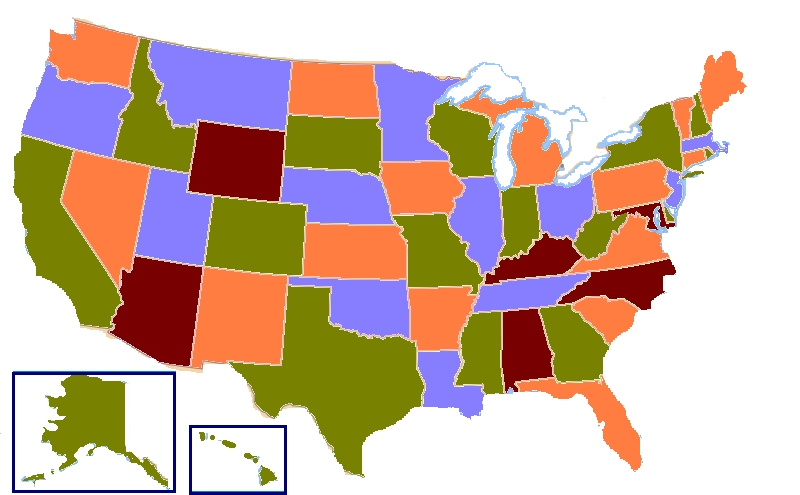

The Four Color Theorem states that the regions of any map can be colored in at most four colors such that no two adjacent regions are colored with the same color. We can use Dimple to solve the Four Color problem by reducing it to a SAT.

Let's look at of a map of size N=3. We will use 4*N variables named Ri,

Bi, Gi, Yi, each corresponding to coloring the ith map region in their

respective color or not. This means that for each i, one and only one color

variable must be true. Thus we need one (Ri or Bi or Gi or Yi) clause for each

i. This states that we need at least one color for each region. And then for

each pair of colors C1 and C2 we need a (-C1i or -C2i) clause for each

i, stating that two colors can not be selected for the same region. Finally,

for each neighboring region we need a (-Ri or -Rj), indicating that they

cannot both be of the same color.

The SAT for a complete 3-vertex graph (N=3) looks like this:

(and

; region 1

(or R1 B1 G1 Y1)

(or (not R1) (not B1))

(or (not R1) (not G1))

(or (not R1) (not Y1))

(or (not B1) (not G1))

(or (not B1) (not Y1))

(or (not G1) (not Y1))

; region 2

(or R2 B2 G2 Y2)

(or (not R2) (not B2))

(or (not R2) (not G2))

(or (not R2) (not Y2))

(or (not B2) (not G2))

(or (not B2) (not Y2))

(or (not G2) (not Y2))

; region 3

(or R3 B3 G3 Y3)

(or (not R3) (not B3))

(or (not R3) (not G3))

(or (not R3) (not Y3))

(or (not B3) (not G3))

(or (not B3) (not Y3))

(or (not G3) (not Y3))

; adjacent

(or (not R1) (not R2))

(or (not R1) (not R3))

(or (not B1) (not B2))

(or (not B1) (not B3))

(or (not G1) (not G2))

(or (not G1) (not G3))

(or (not Y1) (not Y2))

(or (not Y1) (not Y3)))Running this through Dimple gives 24 solutions. In this simple case, we have a

valid solution whenever we select three distinct colors, which we can do in 4!

ways. To automate the reduction of such a problem, we will introduce a new

interface: Reduction.

@FunctionalInterface

interface Reduction<P> {

public Formula reduce(P problem);

}Now, given the correct reduction, we can solve any problem simply by reduction to SAT:

class ReductionSolver<P> {

private final Reduction<P> reduction;

private Solver createSolver(P problem) {

return Formulas.createSolver(reduction.reduce(problem));

}

Optional<Map<String, Boolean>> solve(P problem) {

return createSolver(problem).solve();

}

}And finally we can implement the reduction like this:

class FourColorReduction<T> implements Reduction<Graph<T>> {

@Override

public Formula reduce(Graph<T> graph) {

var builder = new FourColorSexpressionBuilder(graph);

builder.writePrefix();

builder.writeAllRegions();

builder.writeAllEdges();

builder.writeSuffix();

return Sexpressions.compile(builder.get());

}

private class FourColorSexpressionBuilder {

// ...

}

}Our automated solver will now allow us to solve the Four Color Problem for much

larger maps, such as the map of the United States or America. We simply need to

generate a graph which is equivalent to the map and pass it to our solver. A

decode function is used to take the SAT solution and convert it to a mapping

from a state name to a color. Example code can be found in

FourColorReductionTest.

var solver = ReductionSolver.of(new FourColorReduction<String>());

var solution = solver.solve(mapOfUsa()).get();

var colorMap = FourColorReduction.decodeSolution(solution);A clique is a fully connected graph within another graph, an N-clique has N

vertices. Finding a clique of size N within a graph is one of

Karp's 21 NP-complete problems,

and interestingly, is also reducible to SAT. This time, we will go about

automatic the reduction immediately, as even the smallest Clique Problem can

introduce hundreds of clauses.

According to

this page,

to reduce a Clique Problem to a SAT, we need to N*V variables, where V is

the number vertices in a graph and N is the size of the clique. For each r

from 0 to N, Vi,r is true if Vi is the rth node of the clique. Using

this, we can add the following clauses:

(V1,r or V2,r or ... or Vn,r)for allrs.t.0 <= r < N.(-Vi,r or -Vi,s)for alli,r,s,0 <= r < s, s.t.0 <= s < N(A vertex cannot be both therth and thesth vertex in the clique).- If there is not edge from

VitoVj, they cannot both be in the clique. Thus, we add-Vi,r or -Vj,sfor all s.t.0 <= r, s < N,r != s.

This gives

CliqueReduction:

class CliqueReduction<T> implements Reduction<Clique<T>> {

@Override

public Formula reduce(Clique<T> clique) {

var builder = new CliqueSexpressionBuilder(clique);

builder.writePrefix();

builder.writeRthVertex();

builder.writeMutualExclusion();

builder.writeEdges();

builder.writeSuffix();

return Sexpressions.compile(builder.get());

}

private class CliqueSexpressionBuilder {

// ...

}

}You can view the test by looking at

CliqueReductionTest.

The graph being tested is identical to the one in the next figure. The generated

SAT instance has 28 variables and 284 clauses, but Dimple can solve it in under

a second.

In the above diagram, a brute force algorithm is applied to search for a clique of size 4.

Sudoku is a classic problem for SAT

solvers. A reduction from Sudoku to SAT can generate over 1000 clauses and N^3

variables, where N is the size of one side of the Sudoku.

To reduce to SAT we name each variable Xi,j=v, for all i, j, v s.t.

1 <= i, j, v <= N, if the variable is true, the cell at i, j has the value

v. Then the clauses are simply:

ExactlyOneOf(Xi,j=1, Xi,j=2 ... Xi,j=N)for alli,j. This mean we must have a value for each square.ExactlyOneOf(X1,j=v, X2,j=v ... XN,j=v)for allj,v. This means that rows cannot contain duplicate values.ExactlyOneOf(Xi,1=v, Xi,2=v ... Xi,N=v)for alli,v. This means that columns cannot contain duplicate values.ExactlyOneOf( (Xi+0,j+0=v, Xi+0,j+1=v ... Xi+0,j+sqrt(N)=v), (Xi+1,j+0=v, Xi+1,j+1=v ... Xi+1,j+sqrt(N)=v) ... (Xi+sqrt(N),j+0=v, Xi+sqrt(N),j+1=v ... Xi+sqrt(N),j+sqrt(N)=v) )for alli,j,v. This is the hardest constraint to read (if only GitHub supported LaTeX...), it just means that squares cannot contain duplicate values.- Finally, the constraints of the puzzle itself are encoded as a clause for

every known value. For example, if we know square 1,2 has the value 5, a

constraint

X1,2=5is added (and hence must be true).

ExactlyOneOf(...) is a helper function, recall from the Four Color example

that it can be transformed into a "regular" boolean formula by adding the

following clauses:

(V1 or V2 ... Vn)for all variables in the argument list.(-Vi -Vj)for alli,js.t.i != j.

Finally, a brief overview of the code looks like this:

class SudokuReduction implements Reduction<int[][]> {

@Override

public Formula reduce(int[][] sudoku) {

Preconditions.checkArgument(isSudoku(sudoku), "Sudoku is invalid");

var builder = new SudokuSexpressionBuilder(sudoku);

builder.writePrefix();

builder.writeValueForEachSquare();

builder.writeDedupedRows();

builder.writeDedupedCols();

builder.writeDedupedSqrts();

builder.writePuzzle();

builder.writeSuffix();

return Sexpressions.compile(builder.get());

}

boolean isSudoku(int[][] sudoku) {

for (int i = 0; i < sudoku.length; i++)

if (sudoku[i].length != sudoku.length)

return false;

int sqrt = IntMath.sqrt(sudoku.length, RoundingMode.FLOOR);

return sqrt * sqrt == sudoku.length;

}

private class SudokuSexpressionBuilder {

// ...

}

}Dimple's SudokuReduction

can make quick work of any 4x4 Sudoku puzzle using this method. When trying to

solve a 9x9 puzzle it chokes because of its recursive parsing of the formula

(see

FormulaSolverVisitor).

This can be fixed, but for the purpose of this exercise I think solving a 4x4 is

enough.

Sudoku puzzles are usually categorized by their difficulty, "easy", "medium", "hard", etc. Modern SAT solvers are good enough to be able to solve any of the hardest Sudoku puzzles regardless or their difficulty with ease. In contrast, dedicated naive Sudoku solvers can sometimes choke on harder problems. Check out Peter Norig's article on Sudoku solvers for a more extensive review of solving Sudoku puzzles using a dedicated solver.

SAT solvers are incredibly powerful programs with many many applications. So many problems can be reduced to SAT, and using a modern fast SAT solver can be solved in milliseconds.

If you'd like to lean more about SAT solvers, check out Sahand Saba's Understanding SAT by Implementing a Simple SAT Solver in Python which is the blog post that inspired this write-up, and of course Knuth's TAOCP section 7.2.2.2 which goes into a lot of detail on the subject. Additionally, Modern SAT solvers: fast, neat and underused (part 1 of N) and Sudoku solving the easy way using boolean satisfiability discuss successfully solving a Sudoku using a SAT solver in more detail.