Distracted driving is a very deadly condition on the roads, and it is aggravated when drivers and passengers refuse to wear their seatbelts. Iris is intended to be a vehicle safety program that will detect when users are wearing seatbelts, for use in insurance and fact-finding. This paper attempts to build on the work in the YOLO CNN architecture as well as the work of others on the Kaggle dataset for distracted driving provided by Statefarm. We compare results from the Statefarm dataset with a broader goal of detecting all distracted driving, to a custom but smaller dataset that is focused only on detecting seatbelt usage. Our team managed an 86% accuracy rate on the larger dataset and about an 80% accuracy rate on the smaller dataset, average across three different neural networks. This work shows that maybe lots of smaller questions are going to be easier to solve than one big one at a time, even with a smaller dataset. These results are tempered by the fact that our team had only small amounts of data. These results are tempered by the fact that our custom dataset was very small, and we are not confident with the results. The team does not believe that this program should be released as it stands.

According to the CDC, 1.35 million people are killed on roadways around the world each year, caused by drunk driving, drowsiness, distracted driving, and or preventable mistakes such as not wearing a seatbelt. Seat Belt detection systems in cars cannot actually tell if someone is wearing theirs correctly, since they only detect whether it has been “clicked in’’. Similarly, other measures such as the “hands on the wheel” heuristic attempt to provide a proxy for the information but may not solve the issue itself. By using computer vision to directly classify whether a person is actually wearing their seatbelt properly, or whether they are focusing on the road, we can improve driver safety and provide useful information in the event of an at-fault scenario, and hopefully prevent these scenarios entirely with our application. In order to implement this system, we’ll have to find or generate an acceptable bank of images to use for classification. This may be a challenge, since we don’t think the specific application we are trying to build has been done. If we can get an 70% accuracy rating, we think that would make our project feasible, given the size of our data bank. Deployment of our system would happen as a web app where you can upload pictures and receive a response, but a reach goal would be to implement this as a part of the car’s system.

There exists research around seatbelt detection. Since our application will run in real-time, performance is an important factor. Kashevnik et al. developed a seatbelt detection model using the YOLO neural network architecture. YOLO is a convolutional neural network (CNN) for doing object detection in real-time. The algorithm applies a single neural network to the full image, and then divides the image into regions and predicts bounding boxes and probabilities for each region. YOLO provides a significant performance boost over conventional CNNs because it is optimized for real-time applications. Nonetheless, it is important not to sacrifice accuracy when improving performance. This model achieved a 93% accuracy, which provides a good benchmark for our testing. Chen et al. used CNNs to detect whether seat belts were being worn, much like ours will. They claim that most other models depend on edge detection, however this paper argues that it is not always dependable, since the type and layouts of cars differ. Their model is an amalgamation of two other models: one which exists to extract more features and one which actually trains using those new features. They argue that this is more effective.

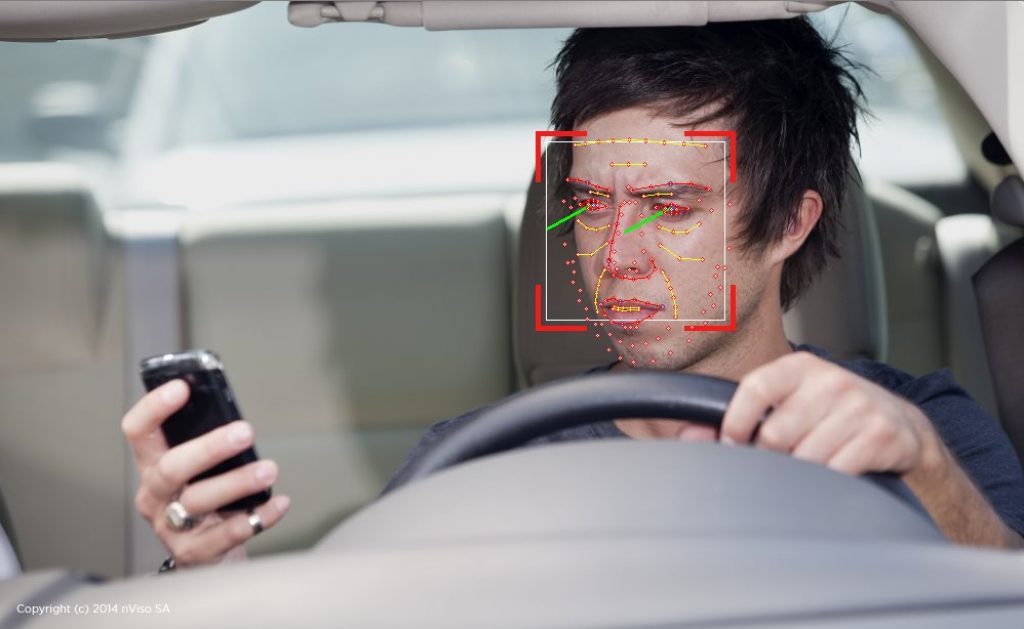

There is significant existing research around monitoring driver attentiveness. Many applications involve mounting cameras on the steering wheel, dashboard, or front seats to capture a video stream of the driver and their surroundings. F. Vicente et al. introduces a system to monitor driver gaze and accurately detect when the driver’s eyes are on/off the road ahead. The system captures a driver’s facial features and creates a 3D rendering of their head pose and gaze direction. With this information, the system detects eyes off road (EOR) with about 95% overall accuracy, and these results are consistent for drivers of different ages, sizes, colorings, eyewear, and conditions of illumination (spectrum from sunny days to nighttime). Importantly, the system’s use of geometric reasoning removes the need for major recalibration whenever there is a new driver or the camera position changes. Vural E. et al. used 30 classifiers to detect various head and facial movements, such as yawning and blinking patterns. Unlike other research, they didn’t pre-assume anything about any of the features. So for example, they didn’t initially give any weight to blink rate, etc. They used unsupervised learning to track all of the features and have the system itself classify them drowsy. Using this method, they achieved 90% accuracy across subjects which they claim is the highest prediction rate reported to date for detecting real drowsiness.

The systems mentioned above were both simple to implement and remarkably successful in detecting driver focus and the presence of distracting objects. A logical next step, which seems feasible after surveying existing research, would involve piecing these safety measures together to create a more comprehensive driver safety/attentiveness system.

To train our models, we utilized PyTorch and its libraries. We trained our models on Pomona's High Performance Computing (HPC) servers, taking advantage of the GPUs. Based on previous research, CNNs have achieved some of the best accuracies for our use case, so that is the model we chose. In addition, we experimented with transfer learning using a pre-trained resnet-18 model. We captured our data using a cell phone camera from a center-of-dashboard angle. Furthermore, we are investigating different deployment options for a web-based application of the Iris system.

In building this model, we knew that we needed to use transfer learning to extend a CNN trained on real-world images, as existing projects that utilized transfer learning achieved higher accuracies than those that did not. PyTorch supports many options trained on the ImageNet dataset, which contains millions of these inputs. We tried VGG , AlexNet, and ResNet and found that an 18-layer version of ResNet consistently had the best performance on our validation set -- though the margin was slim and any choice would’ve delivered similar results. The max overall validation accuracy for each transfer learning architecture over 5 trials was 83.4%, 84.7% and 86.6%, respectively.

Similarly, we tried several optimizers supported by Pytorch, including AdaGrad, Adam, SGD, and RMSProp, and found that Adam delivered the best validation accuracy. We decided to use the Cross Entropy Loss function because it is so familiar from our in-class work. For the remaining hyperparameters in our model (epochs, batch size, image size, dropout rate), we used the strategy employed during lecture of adjusting up or down by powers of two and then tweaking to find the optimal values. In the end, we trained our model for 10 epochs with a batch size of 64, 224 x 224 images, and a 0.4 dropout rate in the second to last layer.

During training, both measures of loss (training and validation) consistently and steadily declined for all epochs. The opposite is true for our accuracy measures, which monotonically increased (graphs below). We are unsure why validation accuracy is higher than training accuracy, yet we will continue to investigate this. We tried increasing the number of training epochs past 10 but found that performance usually plateaued around there. Wary of overfitting, we stuck to this number. We encountered cases where the model was thrown off, and predicted 100% for one class.

We were pleasantly surprised by the final model’s performance, which achieved 86% accuracy on the whole validation set of 4485 images. The winning submissions in the Kaggle competition where our data comes from all had multiclass losses below 0.10. The best publicly visible models we found in blog posts and github repos had validation accuracies between 90-95% (all of which employed fancy data science and ML techniques outside the scope of our class). Looking at a breakdown of accuracy for each class, we see that most values are close to the model’s average total accuracy, with a few notable exceptions. If someone is distracted and putting on makeup, our model predicts the correct label only 68% of the time. On the other hand, our model will correctly label images of people talking on the phone with their left hand 93% of the time.

Accuracy on validation set: 3885/4485 = 86.62%

Accuracy on safe driving class: 438/524 = 83.59%

Accuracy on texting - right class: 374/423 = 88.42%

Accuracy on talking on the phone - right class: 402/454 = 88.55%

Accuracy on texting - left class: 412/474 = 86.92%

Accuracy on talking on the phone - left class: 448/478 = 93.72%

Accuracy on operating the radio class: 415/446 = 93.05%

Accuracy on drinking class: 391/467 = 83.73%

Accuracy on reaching behind class: 369/396 = 93.18%

Accuracy on hair and makeup class: 260/380 = 68.42%

Accuracy on talking to passenger class: 376/443 = 84.88%

It’s difficult to guess why our model is better at knowing that someone is talking on the phone with their left hand vs. their right, especially since the camera captures images from the drivers right profile. Our model is also relatively weaker at guessing when someone is drinking, which is surprising given the uniqueness of this motion and how it looks in photos. Let’s visualize some of the model’s predictions to see if we can glean any insights.

As we’d expect, our model correctly labels some images and misses others. Instead of visually scanning all these predictions and guessing where our model underperforms, we can use a confusion matrix to summarize where our model gets “confused.” This visual will show us what classes are most difficult for our model to distinguish between. Numbers along the main diagonal show how many times our model correctly predicts the label of images belonging to a particular class. Looking horizontally at the values in a given row, we see how frequently our model incorrectly labels images in this class as belonging to each different class. High values off the main diagonal indicate that our model is struggling to differentiate between two classes, and we should adjust our dataset or training methods to lower this specific type of miss. The plot below includes data from the whole validation set and shows the number of times our model predicted class X and the true label was class Y. All classes are evenly distributed. Looking at this plot gives us an idea of where our model has the most room to improve. For the model’s worst class, fixing hair and makeup, the misclassifications are spread fairly evenly across the other image classes -- a potential solution might be to simply add more “hair and makeup” images to the training set. It’s also possible, however, that this class will remain a weak point for the model, given how similar this task looks to talking on the phone (either side) and drinking. Comparing classes in a pairwise manner, we see that our model had the hardest time differentiating pictures of people driving safely and talking to the passenger. It incorrectly guessed that a safe driver was talking to a passenger 22 times, and predicted that someone distracted by their passenger was safely driving 32 times. Naturally, we could improve the model’s performance by specifically training it to distinguish between these two classes.

For this model, we created our own dataset. We did so by asking friends and family to join us in taking pictures of themselves inside of a car. We took half the pictures with a seatbelt on and half with it off, varying poses and positions every time.

We arrived at our “final” model by following similar steps to what we did in the larger Distracted Driver model. We tried all of: a linear neural network, a convolutional neural network, and a pre-trained resnet from pytorch. The goal was to compare these models and see how far we could get with our smaller dataset and a laser-focused question - can we detect the presence of a seatbelt in an image?

The answer turned out to be yes, mostly. On average over the three models, we got about an 80% accuracy. Here’s what that looked like for each of them.

model = model = nn.Sequential(

nn.Flatten(),

nn.Linear(3 * 128 * 170, 100),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(100, len(CLASSES)),

nn.Dropout(dropout_rate)

)

criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

optimizer = optim.Adam(model.parameters())

# Train this model

model = train_model(model, criterion, optimizer, num_epochs)

Training loss at epoch 0/10: 11.9242

Training loss at epoch 1/10: 11.4041

Training loss at epoch 2/10: 10.7373

Training loss at epoch 3/10: 7.1861

Training loss at epoch 4/10: 4.3464

Training loss at epoch 5/10: 3.8706

Training loss at epoch 6/10: 2.2134

Training loss at epoch 7/10: 1.2902

Training loss at epoch 8/10: 1.3053

Training loss at epoch 9/10: 0.9176

Accuracy on validation set: 22/28 = 78.57%

Accuracy on belt_on class: 7/13 = 53.85%

Accuracy on no_belt class: 15/15 = 100.00%

Training loss at epoch 0/10: 7.3959

Training loss at epoch 1/10: 1.5326

Training loss at epoch 2/10: 1.5171

Training loss at epoch 3/10: 1.3136

Training loss at epoch 4/10: 1.2779

Training loss at epoch 5/10: 1.1754

Training loss at epoch 6/10: 1.0913

Training loss at epoch 7/10: 1.0067

Training loss at epoch 8/10: 0.8577

Training loss at epoch 9/10: 0.7110

Accuracy on validation set: 22/28 = 78.57%

Accuracy on belt_on class: 10/13 = 76.92%

Accuracy on no_belt class: 12/15 = 80.00%

Training loss at epoch 0/10: 16.3037

Training loss at epoch 1/10: 3.3240

Training loss at epoch 2/10: 0.1413

Training loss at epoch 3/10: 0.0085

Training loss at epoch 4/10: 0.0782

Training loss at epoch 5/10: 0.0012

Training loss at epoch 6/10: 0.0065

Training loss at epoch 7/10: 0.0004

Training loss at epoch 8/10: 0.0349

Training loss at epoch 9/10: 0.0009

Accuracy on validation set: 22/28 = 78.57%

Accuracy on belt_on class: 7/13 = 53.85%

Accuracy on no_belt class: 15/15 = 100.00%

Most of our time was spent on the convolutional model, since we felt that it had a higher chance of being successful We thought this because a large part of the question we were asking had to do with having certain pixels in certain areas, and from our discussion of CNN’s in class, it seemed simple enough to try to find diagonal lines. It did end up relatively successful, although not before causing some headaches.

The biggest issue was a tendency to overfit the data. Our first iterations of the model would decide to label all of the images with one class, achieving 100% accuracy in that one and 0% on the other. This roughly equaled 50% chance, since our images were very evenly split between the two classes. In order to alleviate these issues, we instituted a 15% dropout rate, which didn’t seem to do much on its own. When we combined that with a higher number of epochs (4 -> 10), we saw a lot more success. Switching to the transformed data also yielded better results.

The resnet was a pre-trained model, which we used as a sort of baseline to compare our other models. It performed well, although it required increasing the number of epochs also.

In all, after playing with the following hyperparameters, we learned the following: Epochs: more was generally better. We settled on about 10. Dropout: We saw the best improvements at about a 15% dropout rate. Pooling: we ended up actually removing the pooling layers for our CNN, since they seemed to be increasing the complexity a lot (and thus debugging time) and we got alright output with them.

The Distracted Driver classification problem is slightly different because we are performing multi-class classification, and have access to a dataset that is fairly good quality. On the other hand, the seat belt classification problem is a binary classification problem for which we had to create our own dataset. At the core, we are performing image classification in both problems, so we use CNNs for both, changing the architecture as needed. Nevertheless, the different datasets required different architectures. For example, the resnet-18 model achieved an accuracy of 86% for the Distracted Driver problem, while it only achieved 79% accuracy in the seat belt problem. A simpler, built from scratch CNN performed better in the seat belt problem.

The seat belt classification problem required most of our efforts to go towards creating and labeling our own dataset, which is itself a completely different problem. The Distracted Driver distracted driver dataset contains thousands of images of a diverse group of individuals, which we were not able to replicate for our seat belt dataset. Our dataset was curated by ourselves and our friends and family, and thus our model is biased. Given this, we hypothesize that our model will not achieve the same accuracies if deployed in a real-life scenario.

Our model is trained off a limited set, collected from pictures of ourselves and our friends and family. This is fine for learning, but as it stands, it shouldn’t be published. After reviewing it ourselves, we have a variety of concerns.

One of the potential applications that we imagined was sending this information to insurance companies in the case of accidents and collisions. In our view, a good model would eliminate some of the human biases of insurance adjusters looking through the data themselves. However, our data set is so small that we’re not confident it would actually reduce bias, and could have harmful outcomes.

For one, our data set isn’t diverse enough. If we were to ship a model that could only recognize seatbelts on certain body types or skin colors, we could do serious financial damage to vulnerable groups, as insurance prices would probably rise for anyone who our model tagged as not wearing a seat belt. They may even face fines or judicial punishments, since not wearing a seatbelt is a misdemeanor in most cases.

Another issue is privacy. In order for our product to work, cars would need to be equipped with a camera system. Insurance companies or even governments might see fit to regulate the presence of these cameras into a vehicle, providing yet another potential financial burden for drivers, as well as a huge privacy concern for those who wouldn’t like to be recorded for the entirety of their drive.

Additionally, in order to provide an accurate report of whether the driver was wearing their seatbelt, our camera system would need some sort of recording functionality, and perhaps even the ability to broadcast. If a driver was able to look at and delete footage, we might be aiding attempts to obstruct justice (since they would probably want to delete footage in which they were not wearing a seatbelt, and might use the lack of evidence in their argument). Alternatively, if the user wasn’t given that option, and instead reporting fell to some other party, we might be putting drivers in a situation where they are having to incriminate themselves with their own products. This issue is balanced against the fact that not wearing a seatbelt is legitimately a public health hazard. All around, it’s a difficult topic to address, and might give us some hesitations moving forward with the implementation.

As mentioned above, proper implementation of our model requires a user to buy and install a camera in their cars. If the installation is mandated, that may be a huge financial burden, especially for underprivileged groups for whom it may make up a significant portion of the car’s price.

Insurance rates would also probably increase for those whom our model has tagged as “unsafe”. If the model is wrong, we could be causing a huge financial burden incorrectly. Even worse, we could be skewing data about which groups drive unsafely, which could increase rates for an entire population.

If we had more time to work on Iris, we would invest it into curating a more diverse dataset that is representative of the general U.S. population. Although we have developed a model that detects if drivers are wearing seatbelts with fairly high accuracy, most of our sample contained White or light-complected people, which is often a problem in image classification applications. Therefore, we would see the most improvement in creating a more robust dataset. In addition, there are other classification problems we would like to solve in the future, as part of Iris' goal of increasing driver safety. These classification problems include: driver gaze detection, passenger seat belt detection, and passenger activity detection, all to provide more context to the computer monitoring cabin conditions. A long-term goal is to deploy this as an in-cabin system that provides real-time analysis by running all of the Neural Networks in parallel.

Chen, Yanxiang, et al. “Accurate Seat Belt Detection in Road Surveillance Images Based on Cnn and Svm.” Neurocomputing, vol. 274, 2018, pp. 80–87., doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2016.06.098.

F. Vicente, Z. Huang, X. Xiong, F. De la Torre, W. Zhang and D. Levi, "Driver Gaze Tracking and Eyes Off the Road Detection System," in IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 2014-2027, Aug. 2015, doi: 10.1109/TITS.2015.2396031.

Kashevnik, A., Lashkov, I., Shilov, N., Ali, A., & 26th Conference of Open Innovations Association FRUCT, FRUCT 2020 26 2020 04 23 - 2020 04 24. (2020). Seat belt fastness detection based on image analysis from vehicle in-cabin camera. Conference of Open Innovation Association, Fruct, 2020-april, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.23919/FRUCT48808.2020.9087474

Vural E., Cetin M., Ercil A., Littlewort G., Bartlett M., Movellan J. (2007) Drowsy Driver Detection Through Facial Movement Analysis. In: Lew M., Sebe N., Huang T.S., Bakker E.M. (eds) Human–Computer Interaction. HCI 2007. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 4796. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/978-3-540-75773-3_2