Research Paper on Algorithms for the Travelling Salesman Problem

The travelling salesman problem (TSP) can be stated as follows:

"A traveling salesman wants to visit each of $n$ cities exactly once and return to his starting point. In which order should he visit these cities to travel the minimum total distance?" 1

On the surface the problem sounds very simple. However, in reality finding the optimal solution proves to be very difficult, especially as the number of cities increases.

This problem can be defined mathematically using graphs. With the cities represented by vertices and the distances between each city represented by weighted edges. This graph can be considered to be fully connected, meaning that each vertex is connected to each other by an edge.

Another quality of this graph is that weight of the edges represents the shortest distance between those two nodes. This is to say that there cannot exist a path with a shorter distance where an intermediate vertex is visited. This quality is also known as the triangle inequality. Mathematically this quality can be represented as

The condition that the salesman must return to the starting point can be defined mathematically as a tour which is a walk over a graph that has no repeated edges and starts and ends on the same vertex.

Note there are variations to this problem where certain constraints are relaxed, making the problem simpler and easier to solve. However, for the purposes of this paper the above conditions were applied.

A more rigorous mathematical formulation in the form of an integer linear program can be found in the textbook Nonlinear Programming by Dimitri Bertsekas.3

One of the earliest mentions of this problem could be found in a handbook for travelling through Germany and Switzerland4. However, the first mathematical formulation of the problem can be traced to the 19th century by William Rowan Hamilton and Thomas Kirkman. A more general formulation would be studied by Karl Menger in the 1930s in Vienna and Harvard.5

This problem is important in the theoretical computer science community since it is one of the problems that is proven to be NP-hard. This means that the optimal solution of this problem can be found in polynomial time but only if there exists an NP-Complete solution with polynomial time that the original problem can reduce to. In the case of the travelling salesman problem, the problem can be reduced to finding the optimal Hamiltonian cycle which is in NP Complete.6

As for the applications of this problem, the obvious application of this problem would be in optimization the path for a delivery person to take while delivering packages. These algorithms have also been used to solve optimal placement of components in printed circuit boards such that the wiring between components can be optimized.7

Algorithms Used

In this report three algorithms were implemented. Namely, the brute force algorithm, the dynamic programming and the Christofides–Serdyukov algorithm. All three algorithms were implemented using python. Note the brute force and dynamic programming algorithms both find the optimal solution since they search the whole solution space. The Christofides-Serdyukov algorithm only provides an estimate. However, because of the accuracy trade-off the Christofides-Serdyukov algorithm is typically many times faster, depending on the implementations of the sub algorithms. This tradeoff is shown very clearly through the experiments which are shown later in the paper.

Understanding the Complexity of the problem

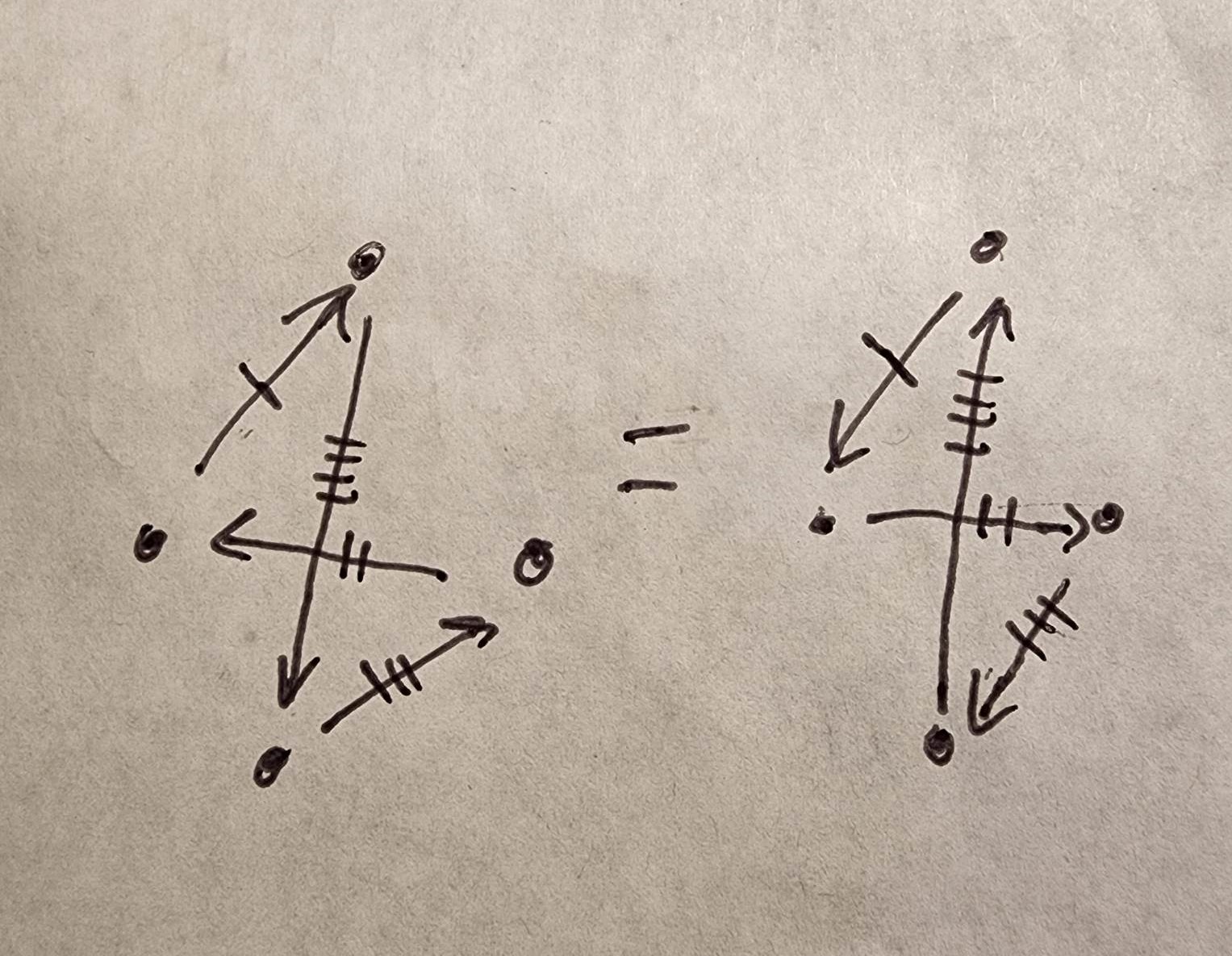

The difficulty can be seen through trying to solve this problem using the most naïve algorithm which the brute force method where every tour is considered. The total possible tours can be understood by finding the number of unique permutations of ordering the nodes and then dividing by two. This is because a permutation represents the order in which the nodes can be visited and this number is divided by 2 since reversing the order will return a tour with the same cost. This is illustrated in the picture below.

the distance is the same between arrows with the same number of marks

Therefore, the number of possible tours can be given by the following equation, where

If the

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 12 |

| 6 | 60 |

| 7 | 360 |

| 8 | 2520 |

| 9 | 20160 |

| 10 | 181440 |

| 11 | 1814400 |

Note in all these problems the start node is assumed to be the first node. In other implementations a start node can be specified. This may help decrease the search space depending on the algorithm but technically this should not matter since each tour must visit each node.

The brute force method was eluded to in the previous section. The pseudo code is as follows:

Algorithm: Brute Force

Input: Fully Connected Graph

Output: Minimum Tour and cost of tour

F(graph):

# from graph obtain nodes

nodes = graph.nodes_list

# define recursive function to find permutations of all nodes

def recursive_function(current_tour, remaining_nodes, solution)

# Base case

if remaining == None:

if reversed not in solution

Add to solution

# Recursive case

for remaining nodes:

recursive_function(current_tour + new_node, remaining node - new_node, solution)

# Initialize loop

recursive_function(nodes[0], nodes - nodes[0], solution_list)

# Parse through solution list to find minimum weight (linear time)

return min(solution)

To summarize the method behind this algorithm is to find every single permutation and then find the minimum cost out of all the found solutions. The time complexity of this algorithm is

In this algorithm while creating the permutations the subgraph formed by the partial tour is saved such that they don't need to be traversed again. When exploring a new node two pieces of data is required to index the memoized data: the set of visited nodes and the index of the last visited node which represents the order. From this we can calculate the space complexity, which is

The time complexity is

Algorithm: Dynammic Programming

Input: Fully Connected Graph

Output: Minimum Tour and cost of tour

F(graph):

# note start node is assumed to be the first node in list

start = graph.nodes_list[0]

# get graph lenght from adjacency matrix (or length of nodes list)

length = size(graph.adjacency_matrix)

# initialize 2D matrix for memoization, first dimension is number of

nodes and second dimension is the binary representation of the state.

store = matrix[length][2^length]

# update store for first node

update_store()

# solve for the remaining graph using stored data

solve()

# solve for min cost using memoized data and find optimal tour

cost = find_min_cost()

tour = find_min_tour()

# store starting data in matrix

def update_store(graph, store, length)

for i in range(node):

if node == start:

continue

# note second dimension is a binary representation

store[i][1 << start | 1 << i] = graph.get_weights[start, node]

def solve_subproblem(graph, store, length)

# Note loop starts from 3 since first edge considers 2 nodes, so the

next iteration is the third node

for r in range(3, N):

# use another function to obtain every combination with one more

node than current state

for subset in combinations(r, N):

# skip if start is not in subset

if start not in subset:

continue

# consider all nodes

for next in all nodes:

# skip of next is the start node or next is not in subset

if next == start or next not in subset:

continue

# need to find best state using memoized data

so first take away next from subset using bit

manupulation, also intialize variable for min distance

state = subset ^ (1 << next)

min_distance = +inf

# loop through

for end in all nodes:

# skip if not under following conditions

if end == start or end == next or end not in subset

contine

# calculate distance if node 'end' is added use

stored data

new_distance = store[end][next] + graph.get_weights[end, next]

# check if need to replace min distance

if new_distance < min_distance

min_distance = new_distance

def combinations(r, N)

# This can be one using recursive function

return every combination state from r to N

def find_min_cost(graph, store, length)

# note end state is always the binary representation with all ones

since every node is visited

end_state = (1 << N) - 1

min_tour_cost = +inf

# loop through stored array for tours with end state and find minimum

for node in all nodes

# skip if node is start since that entry is 0

if node == start:

continue

# need to add the weight from end to start

tour_cost = store[node][end_state] + graph.get_weights[end, start]

# replace min_tour_cost if smaller

if tour_cost < min_tour_cost

min_tour_cost = tour_cost

return min_tour_cost

def find_tour(graph, store, length)

# start from initial node and end state, note these variables will change as we traverse backwards

prev_node = graph[0]

state = (1 << N) - 1

# define tour to be empty array or array of size number of nodes

tour = []

for i in range(nodes list)

# need to traverse backwards from state

index = -1

for j in range(nodes list)

if j == start or j not in subgraph:

continue

# check if there is a better a better index than previous, if there is then use that node

prev_dist = store[index][state] + graph.get_weights[index, prev_node]

new_dist = store[j][state] + graph.get_weights[j, prev_node]

if new_dist < prev_dist

index = j

# add to tour

tour.append(index)

# change state

state = state ^ (1 << index)

prev_node = index

# add first node to the end since need to start and finish on first node

tour.append(graph[0])

return tour

This implementation is based off existing code by William Fisset 9. However, the original code was written in java and various adaptions were made to accommodate the utility functions. Out of all the algorithms implemented, this one was the most complicated since it relies on bit manipulation to store the data and achieve a better time and space complexity than the brute force solution.

This algorithm is the only approximate algorithm considered. Meaning that the solution is not necessarily optimal. However, the tradeoff for accuracy is the speed at which a good tour can be found. According to literature the error ratio, which is the minimum cost found by this algorithm divided by the true optimal cost, has an upper bound of 1.59. However, this also relies on the optimality of the sub algorithms involved.

This algorithm makes use of the similarity of the minimum spanning tree and the optimal tour. The minimum spanning tree (MST) is a set of edges with the minimum weight that can connect all nodes in a graph. The difference between a tree and a tour is that a tree cannot have any cycles. Therefore, if the MST was a line adding a single edge to a MST and it would become the minimum tour. However, in a lot of cases it is not that simple. The issue is that in a minimum spanning tree there maybe a lot of nodes with an odd number of edges. On the other hand, in a tour all nodes have an even number of edges since each node can only be visited once.

The Christofides-Serdyukov algorithm10 solves this by first finding the minimum spanning tree, then grouping all the odd degree nodes in a subgraph. Since the original graph is fully connected, the weights between all the odd degrees are known. A minimum weight perfect matching algorithm can be applied to the subgraph. The perfect matching means that each node will have one edge but the whole graph will have an even number of edges by the handshake lemma. These edges are added back to the minimum spanning tree resulting in each node having an even degree. Note this resulting graph is a multi graph since the result from the perfect matching could include edges from the minimum spanning tree. An Eulerian tour algorithm can be applied to the graph since it has an even number of edges at each node. An Eulerian circuit is a path in which every edge is visited exactly once. However, in the TSP requires that each edge can only be used once. Therefore to convert the Eulerian circuit to a tour, the circuit is traversed and if a node has already been visited, then a new edge is created. Because the basis of the tour is a MST the total cost is generally lower and in some cases the optimal tour can be found.

The complexity of this algorithm is derived from the implementations of the sub algorithms. Namely, the algorithm used to find the MST, the algorithm to perform the minimum weight perfect matching and the algorithm to find the Eulerian tour. However, typically the matching algorithm has the highest time complexity. For example, the blossom algorithm has a complexity of

Algorithm: Christofides-Serdyukov

Input: Fully Connected Graph

Output: Minimum Tour and cost of tour

F(graph):

# use function to find minimum spanning tree

mst = mst_algorithm(graph)

# find odd degree nodes from mst

odd_degree_nodes = odd_degree_function(mst)

# using the odd_degree_nodes find the minimum perfect matching graph

# the original graph needed for edge data

minimum_matching_graph = minimum matching algorithm(odd_degree_nodes, graph)

# combine minimum matching graph and mst

combined_graph = multigraph(mst, minimum_matching_graph)

# find Eulerian tour of combined graph

eulerian_circuit = eulerian_tour_algorithm(combined_graph)

# loop through circuit and skip if already in the tour

eulerian_curcuit_nodes = eurlerian_circuit.nodes

tour_order = [eulerian_curcuit_nodes[0]]

for node in eulerian_circuit

if node not in tour_order:

tour_order.append(node)

# use function to parse through list of nodes and find total weight and individual edges

(tour_edges, weight) = find_edges_weights(tour_order)

Below is a summary table of the different complexities of the three algorithms.

| Time Complexity |

Space Complexity |

|

|---|---|---|

| Brute Force | ||

| Dynamic Programming | ||

| Christofides-Serdyukov Algorithm |

From this table, the Christofides-Serdyukov algorithm should be much faster than the dynamic programming and brute force algorithm. But the latter two are guaranteed to give optimal solutions.

Two utility classes were created to help store facilitate the data structures. Namely a graph data structure and a priority queue data structure. The priority queue data structure was used in prim's algorithm. Due to time constraints, the built-in function heapq was used.

import heapq

class graph_class:

def __init__(self, nodes, edges):

"""

Initialize graph class object.

:param nodes: List of strings that represent nodes

:param edges: List of tuples in the format of

(node name (string), node name (string), weight (integer))

"""

self.nodes = nodes

self.edges = edges

self.adjacency_matrix = self.create_adjacency_matrix(nodes, edges)

def create_adjacency_matrix(self, nodes, edges):

"""

Method to create adjacency matrix

:param nodes:

:param edges:

:return: 2D list representing adjacency matrix

"""

# create empty 2D adjacency matrix

# Note need to use for loop to create new list objects

adjacency_matrix = [[0 for i in range(len(nodes))]

for i in range(len(nodes))]

# Loop through the list of edges and assign values to 2D adjacency

# matrix then update neighbor dictionary.

for edge in edges:

index_1 = nodes.index(edge[0])

index_2 = nodes.index(edge[1])

adjacency_matrix[index_1][index_2] = edge[2]

adjacency_matrix[index_2][index_1] = edge[2]

return adjacency_matrix

def get_edge_weight(self, node_1, node_2):

"""

Getter method for edge weight given two nodes

:param node_1:

:param node_2:

:return:

"""

return self.adjacency_matrix[self.nodes

.index(node_1)][self.nodes

.index(node_2)]

class priority_queue:

def __init__(self):

self.queue = []

def is_empty(self):

"""

Method to check if queue is empty

:return: void

"""

return len(self.queue) == 0

def insert(self, weight, node_1, node_2):

"""

Method to insert edges in queue.

:param weight: weight of edge

:param node_1: start node

:param node_2: end node

:return: void

"""

heapq.heappush(self.queue, (weight, node_1, node_2))

def dequeue(self):

"""

Method to dequeue element with highets priority, in this case the

lowest weight.

:return:

"""

return self.queue.pop(0)

In general the code implementation follows closely to the pseudocode. This implementation was also inspired by a Leetcode solution12 but is heavily adapted for solving the traveling salesman problem. Note in this implementation the weight is calculated during the brute force process such that the optimal permutation does not have to be traversed just to find the optimal weight.

def brute_force(graph):

"""

Brute Force algorithm for travelling salesman

:param graph: graph object from utilities

:return: permuations of valid tours, minimum weight

"""

nodes = graph.nodes

permutations = []

weights = []

# find every permutation of nodes in graph using recursive function

def add_to_permutation(current, remaining, solution, current_weight,

solution_weights):

# if no more remaining add to solution list

if len(remaining) == 0:

# if reverse already in list do not append to solution list

if current[::-1] not in solution:

current_weight += graph.get_edge_weight(current[0],

current[-1])

solution.append(current)

solution_weights.append(current_weight)

return

# add a new node to current list

for index in range(len(remaining)):

add_to_permutation(current + [remaining[index]],

remaining[:index]

+ remaining[index + 1:], solution,

current_weight + graph.get_edge_weight(

current[-1], remaining[index]),

solution_weights)

# start with first node and add every other node in list

for index in range(len(nodes)):

add_to_permutation([nodes[index]], nodes[:index]

+ nodes[index + 1:], permutations,

0, weights)

return permutations, min(weights)

Similar to the brute force implementation, the implementation of the dynamic programming follows the the pseudocode closely. As stated in the previous section, the code is based off of an implementation in java8.

class dynamic_programming:

def __init__(self, graph):

"""

Initialize object

:param graph: graph class from utilities

"""

self.adjacency_matrix = graph.adjacency_matrix

self.min_tour_cost = sys.maxsize

self.run_solver = False

self.start_node = 0

self.length = len(graph.adjacency_matrix)

self.subsets = []

self.min_tour =[]

self.solve()

def get_min_tour_cost(self):

"""

Getter method for min_tour_cost

:return: int representing min tour cost

"""

return self.min_tour_cost

def solve(self):

"""

method to solve travelling salesman problem using dynamic

programming

:return: void

"""

# if solver already run then just return

if self.run_solver:

return

# define final state

end_state = (1 << self.length) - 1

# create memoization for dynamic programming

memo = [[0 for i in range((1 << self.length))]

for i in range(self.length)]

# copy first row of adjacency matrix values matrix

for i in range(1, self.length):

memo[i][(1 << 0 | 1 << i)] = self.adjacency_matrix[0][i]

for r in range(3, self.length + 1):

self.combinations(r, self.length)

# for subset in self.combinations(r, self.length):

for subset in self.subsets:

# if start node not in subset then skip

if self.bit_not_in(0, subset):

continue

# parse through next elements

for next in range(1, self.length):

if self.bit_not_in(next, subset):

continue

subset_without_next = subset ^ (1 << next)

min_dist = sys.maxsize

for end in range(1, self.length):

if end == next or self.bit_not_in(end, subset):

continue

# calculate distance

new_distance = memo[end][subset_without_next] \

+ self.adjacency_matrix[end][next]

if new_distance < min_dist:

min_dist = new_distance

# add to memoization

memo[next][subset] = min_dist

# calculate minimum cost

for i in range(1, self.length):

tour_cost = memo[i][end_state] + self.adjacency_matrix[i][0]

if tour_cost < self.min_tour_cost:

self.min_tour_cost = tour_cost

# Using memo find optimal tour

self.min_tour.append(0)

prev_node = 0

state = end_state

for i in range(self.length - 1, 0, -1):

optimal_node = -1

optimal_dist = sys.maxsize

for j in range(self.length):

if self.bit_not_in(j, state):

continue

# calculate distance

if optimal_node == -1:

optimal_node = j

prev_distance = memo[optimal_node][state] \

+ self.adjacency_matrix[optimal_node][

prev_node]

new_distance = memo[j][state] \

+ self.adjacency_matrix[j][prev_node]

if new_distance < prev_distance:

optimal_node = j

self.min_tour.append(optimal_node)

state = state ^ (1 << optimal_node)

prev_node = optimal_node

# append first node at end since need to start and end on same node

self.min_tour.append(0)

self.run_solver = True

def combinations(self, r, n):

"""

method to call recursive function and output combinations

:param r: current number of nodes

:param n: total number of nodes

:return: list of subsets represtented by binary number

"""

self.subsets = []

self.recursive_combinations(0, 0, r, n, self.subsets)

return self.subsets

def recursive_combinations(self, set, at, r, n, subsets):

"""

Recursive function to find combinations

:param set: current set

:param at: current node

:param r: number of nodes

:param n: total number of nodes

:param subsets: list of subsets

:return: void

"""

# if no more elements to add return

if n - at < r:

return

# r elements selected so valid subset found, add to subset list

if r == 0:

self.subsets.append(set)

#

else:

for i in range(at, n):

set ^= (1 << i)

self.recursive_combinations(set, i + 1, r - 1, n, subsets)

set ^= (1 << i)

def bit_not_in(self, node, subset):

"""

Check if node is in set that is represented by binary number

:param node:

:param subset:

:return:

"""

return ((1 << node) & subset) == 0

The implementation for the Christofides-Serdyukov algorithm is slightly more involved than the pseudocode from the previous section due to the number of sub algorithms involved. In this code the prim's algorithm was implemented to find the minimum spanning tree. However, to find the minimum perfect matching and the Eulerian circuit the package networkx was used. This package uses the blossom algorithm13 to find the maximum perfect matching graph. Note the minimum can be found by making all the weights negative and then apply a maximizing function. A linear time algorithm was used to find the Eulerian circuit.

from utilities import graph_class

from utilities import priority_queue

import networkx as nx

def prims_algorithm(graph):

"""

Prim's Algorithm

:param graph: graph from graph utilities

:return: graph with mst edges

"""

# keep set of visited nodes

visited = []

# initialize list to store minimum spanning tree

mst_edges = []

# create priority queue to store edge weights, priority queue will be

# ordered by edge weight such that when an element is popped it will

# have the lowest value.

queue = priority_queue()

# start at first node in list

visited.append(graph.nodes[0])

# add edges from first node to priority queue

for index, weight in enumerate(graph.adjacency_matrix[0]):

if weight != 0:

queue.insert(weight, graph.nodes[0], graph.nodes[index])

while not queue.is_empty():

# pop minimum weight from priority queue.

# note edge is a tuple in the form of

# (weight, start node, end node)

weight, start_node, end_node = queue.dequeue()

# if end node (3rd element in tuple) is in visited then skip

if end_node in visited:

continue

# visit new node and add minimum edge to the minimum spanning tree

# note need to reformat tuple

mst_edges.append((start_node, end_node, weight))

visited.append(end_node)

# add edges from new visited node if not visited

for index, weight in enumerate(graph.adjacency_matrix[graph.nodes

.index(end_node)]):

if weight != 0 and graph.nodes[index] not in visited:

queue.insert(weight, end_node, graph.nodes[index])

# create new graph object with mst

mst_obj = graph_class(graph.nodes, mst_edges)

return mst_obj

def find_odd_degree(mst, graph):

"""

Find nodes with odd degrees in a given minimum spanning tree

:param mst: minimum spanning tree

:param graph: Original fully connected graph

:return:

"""

odd_nodes = []

for row in range(len(mst.nodes)):

sum_degrees = 0

for col in range(len(mst.nodes)):

if mst.adjacency_matrix[row][col] != 0:

sum_degrees += 1

if sum_degrees % 2 == 1:

odd_nodes.append(mst.nodes[row])

# create sub graph containing only odd nodes, note still need edges

# from original graph

number_odd_nodes = len(odd_nodes)

odd_edges = []

for i in range(number_odd_nodes):

for j in range(i + 1, number_odd_nodes):

odd_edges.append((odd_nodes[i], odd_nodes[j], -1 *

graph.get_edge_weight(odd_nodes[i],

odd_nodes[j])))

return graph_class(odd_nodes, odd_edges)

def find_minimum_matching_and_eulerian_circuit(mst, graph):

"""

Method to find minimum matching graphs and eulerian tour.

This method uses the package networkx.

:param mst: minimum spanning tree

:param graph: original fully connected graph

:return: eurlerian tour

"""

# create networkx graph

odd_graph_nx = nx.Graph()

odd_subgraph = find_odd_degree(mst, graph)

odd_graph_nx.add_weighted_edges_from(odd_subgraph.edges)

# odd_graph_nx.add_weighted_edges_from(graph.edges)

matching = list(nx.max_weight_matching(odd_graph_nx,

maxcardinality=True))

# add back weight information to the odd matching subgraph

weighted_matching = []

for pair in matching:

weighted_matching.append((pair[0], pair[1],

graph.get_edge_weight(pair[0], pair[1])))

# combine with original graph

combined_graph = nx.MultiGraph()

combined_graph.add_weighted_edges_from(mst.edges)

combined_graph.add_weighted_edges_from(weighted_matching)

# use networkx method to find eularian tour

eulerian_circuit = list(nx.eulerian_circuit(combined_graph))

return eulerian_circuit

def christofides_serdyukov_algorithm(graph):

"""

Implementation of christofides-serdyukov algorithm

:param graph: fully connected graph

:return: edges of calculated tour and weight of tour

"""

# use prim's algorithm to find mst of graph

mst = prims_algorithm(graph)

# find minimum matching of odd dgree nodes and eularian tour

# note function to get odd degree nodes is called within the function

# to find minimum matching and eulerian tour

eulerian_circuit = find_minimum_matching_and_eulerian_circuit(mst, graph)

# get unique node path

tsp_tour_node_order = [eulerian_circuit[0][0]]

for edge in eulerian_circuit:

if edge[1] not in tsp_tour_node_order:

tsp_tour_node_order.append(edge[1])

# get edges and calculate total weight

total_weight = 0

tsp_tour_edge = []

for index in range(len(tsp_tour_node_order)):

node_1 = tsp_tour_node_order[index - 1]

node_2 = tsp_tour_node_order[index]

tsp_tour_edge.append((node_1, node_2))

total_weight += graph.get_edge_weight(node_1, node_2)

return tsp_tour_edge, total_weight

Test were performed on fully connected graphs with randomly generated weight values. The function used to create the graphs is shown below.

def generate_graph(n):

"""

Function to create fully connected graph object

:param n: number of nodes in graph

:return: graph object

"""

# Generate nodes

nodes = [i for i in range(n)]

# create edges and assign random weights

edges = []

for i in range(n):

for j in range(i + 1, n):

edges.append((i, j, random.randint(1, 2 * n)))

# return graph

return graph_class(nodes, edges)

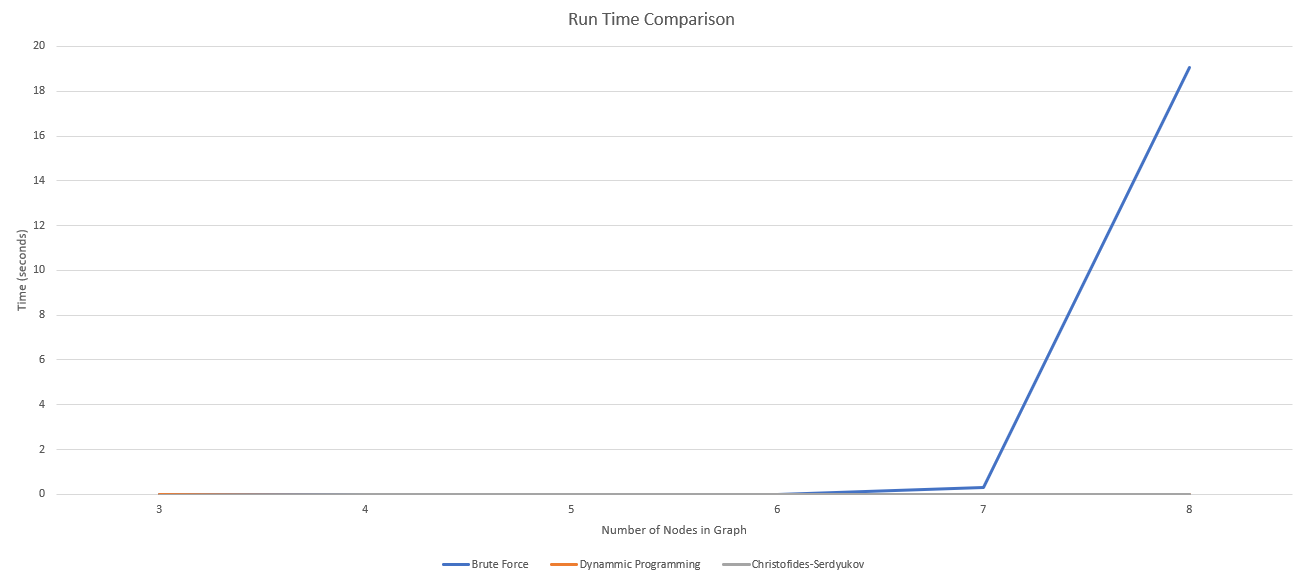

The run times across several graph sizes for all three algorithms were collected. The results are as shown below.

The chart shows how much time the brute force algorithm takes when compared to the other two. To give specific numbers, for graph with 8 nodes, the brute force algorithm required 19 seconds, whereas the dynamic programming and the Chrsitofdes-Seryukov algorithms only requires around a hundredth of a second.

Another chart was produced to compare only the dynamic programming and Chrsitofides-Seryukov algorithm.

This chart shows that the Christofides-Seryukov algorithm is the fastest out of the three algorithms, which was to be expected from the time complexities. Also the space complexity for the dynamic programming could also contribute to the lack of speed at higher node values.

A chart was also produced to see how the Christofides-Serdyukov algorithm would perform on larger graphs.

The largest graph tested had 200 nodes but the peak time was still only 2.16 seconds.

The largest graph tested had 200 nodes but the peak time was still only 2.16 seconds.

The error ratio for the Christofides-Serdyukov algorithm was also tested. The optimal cost was found using the dynamic progaming algorithm. However, this limited the graphs to a maximum of 20 nodes since after that the dynamic programming algorithm would take too long.

Although the theoretical upper bound for the error ratio is supposedly 1.5 there were a few in the experiments that crossed this threshold. I suspect this is due to the maximize perfect matching algorithm as this problem is quite difficult to solve. Another factor could be which node on the Eulerian circuit does the program start on when finding the tour. The implementation always took the first node however it could be possible starting on a different node could yield a lower cost solution.

Although the theoretical upper bound for the error ratio is supposedly 1.5 there were a few in the experiments that crossed this threshold. I suspect this is due to the maximize perfect matching algorithm as this problem is quite difficult to solve. Another factor could be which node on the Eulerian circuit does the program start on when finding the tour. The implementation always took the first node however it could be possible starting on a different node could yield a lower cost solution.

Overall, from a time complexity standpoint the experiments showed what was expected. However, there is some issue in the implementation for the Christofides-Serdyukov as the error seems to be higher than expected.

Through this project I learnt a lot about the travelling salesman problem. I initially chose this problem because I was interested in understanding more about complexity and NP hardness. Having implemented different algorithms with varying complexities but also varying angles of solving the same problem I think I have a better understanding of NP and P. I was also able to use many different data structures in this project, from binary representations to priority queues. Although I believe some parts of this project was rushed I still learnt a lot and will definitely revisit this topic again in the future.

1 - Rosen, Kenneth. Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, 7th ed., pp. 714.

2 -Arindam Khan, Traveling Salesman Problem notes , https://www14.in.tum.de/personen/khan/Arindam%20Khan_files/2.%20metric%20TSP.pdf

3 - Dimitri, Bertsekas, Nonlinear Optimization, 2nd ed., pp. 637

4 - Rosen, Kenneth. Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, 7th ed., pp. 714.

5 - “History of the TSP.” TSP History Home, https://www.math.uwaterloo.ca/tsp/history/index.html.

6 - "Proof that traveling-salesman-problem is np hard", https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/proof-that-traveling-salesman-problem-is-np-hard/

7 - Matai, Rajesh, et al. “Traveling Salesman Problem: An Overview of Applications, Formulations, and Solution Approaches.” Traveling Salesman Problem, Theory and Applications, 2010, https://doi.org/10.5772/12909.

8 - William Fisset, Dynamic programming Travelling Salesman Problem Algorithm in Java, https://github.com/williamfiset/Algorithms/blob/master/src/main/java/com/williamfiset/algorithms/graphtheory/TspDynamicProgrammingIterative.java

9 - Christofides, Nicos. “Worst-Case Analysis of a New Heuristic for the Travelling Salesman Problem.” Operations Research Forum, vol. 3, no. 1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s43069-021-00101-z.

10 - Goodrich, Michael T et al, "18.1.2 The Christofides Approximation Algorithm", Algorithm Design and Applications, Wiley, pp. 513–514. 11 - "Blossom Maximum Matching Algorithm", https://iq.opengenus.org/blossom-maximum-matching-algorithm/

12 - chienhsiang-hung, Leetcode 46 Solution https://leetcode.com/problems/permutations/solutions/2970539/super-simple-brute-force-beats-90-python/?q=brute&orderBy=most_relevant&languageTags=python3

13 - Networkx max_weight_matching source code, https://networkx.org/documentation/stable/_modules/networkx/algorithms/matching.html#max_weight_matching

14 - Networkx eulerian_circuit documentation source code, https://networkx.org/documentation/stable/_modules/networkx/algorithms/euler.html#eulerian_circuit